In her rural Appalachian holler, ten-year-old Misty’s closest friends are the crawdads. She can speak to them, and the birds, and the creek, and everything else too…

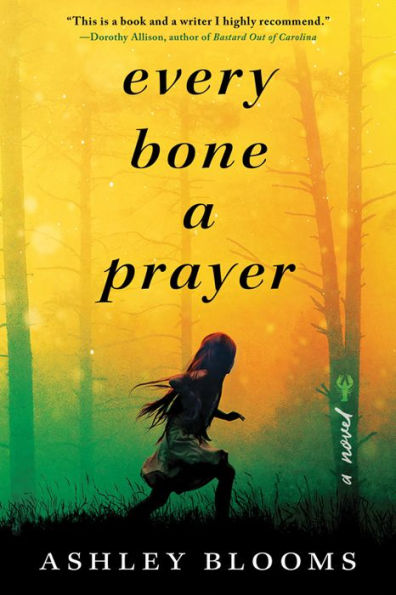

We’re excited to share an excerpt from Every Bone a Prayer, the debut novel from Ashley Blooms—available August 4th with Sourcebooks.

Misty’s holler looks like any of the thousands of hollers that fork through the Appalachian Mountains. But Misty knows her home is different. She may be only ten, but she hears things. Even the crawdads in the creek have something to say, if you listen.

All that Misty’s sister Penny wants to talk about are the strange objects that start appearing outside their trailer. The grown-ups mutter about sins and punishment, but that doesn’t scare Misty. Not like the hurtful thing that’s been happening to her, the hurtful thing that is becoming part of her. Ever since her neighbor William cornered her in the barn, she must figure out how to get back to the Misty she was before—the Misty who wasn’t afraid to listen.

This is the story of one tough-as-nails girl whose choices are few but whose fight is boundless, as her coping becomes a battle cry for everyone around her. Written by a survivor of sexual abuse, Every Bone a Prayer is a beautifully honest exploration of healing and of hope.

Shift

Before a crawdad can grow, it must shed the hard shell of its body.

First, a new skin forms beneath the shell. This skin is soft, but grows stronger.

It is a process of separation, of letting go of the old shape.

A slow goodbye to the body that existed before.

One

Everything that Misty needed was behind her bedroom door, but she couldn’t open it. She planted her toes into the carpet and leaned her full weight against the wood, twisting the knob back and forth. For a moment, the door slipped open, revealing a sliver of darkness about an inch wide. Somewhere inside that darkness was her bed piled high with pillows, her favorite T-shirt, and her box of treasures. Misty stretched her fingers, hoping to slide them through to grab the door, but it slammed shut before she could.

“Penny, let me in,” Misty said.

A muffled “no” came from the other side.

Misty tried again, but her sister was too strong, no doubt digging her heels into the same carpet, her sister two years older and three inches taller, her sister a weight Misty could not move. It would be so much easier if Misty could talk to Penny the way she talked to everything else, so much better without words.

“You can’t keep me out of my own room,” Misty said.

She pushed again, and again the door jerked forward an inch, a space just big enough for Penny’s voice to slip through: “Then go tell Mom on me.”

Buy the Book

Every Bone a Prayer

Misty let go of the door and it slammed back into place. “I can’t.”

On the other side of the trailer, her parents’ voices rose and fell in argument. Misty could only make out every tenth word from behind their closed bedroom door, and those words didn’t make sense alone—won’t, should, really, right, leave. They needed everything in the middle to be complete, all the parts that Misty was missing. Her mother’s voice stood out the most, a sharp spike against the dull rumble of her father’s voice, and together they made a slow, slack creature whose fists pounded against the trailer as it dragged itself closer and closer to Misty.

She slid to the floor and pressed her knees to her chest. Muffled sounds came from behind her, too—Penny crying alone in their room. It would normally hurt Misty to know that her sister was sad, but it only made her angry this time. She pounded her fist against the door, trying to jar Penny’s head. Trying to punish her for shutting Misty out.

But Penny just balled her fist together and punched back, and the wood reverberated between them, their spines pressed to the same spot on the door, and together they made their own strange creature with its own strange heart pounding and pounding.

Misty didn’t stop punching until her father walked out of the bedroom with one hand held in the air and the other empty by his side.

“I’m done talking about this,” he yelled.

Misty’s mother followed him. Her ponytail slumped against her shoulders, little baby hairs catching the light around her face, making her glow. “You don’t get to decide everything on your own, you know that? You’re married. You’re a father.”

“I don’t need you telling me who I am.”

“Apparently you do. You sure seem to have forgot awful quick.”

He snatched his keys from the coffee table and turned toward the door. “Like you’d ever let me forget a damn thing.”

Panic rose in Misty’s chest at the sight of her father leaving. She looked for something to distract her parents with. She’d done it before, stepping between them when they started to argue, holding up her art project or reciting the Bible verses she’d memorized from Sunday school, and the sight of her was often enough to startle them out of their fight. Misty became a blush rising to her mother’s cheek, the spasm of her father’s hand clenching tight and then releasing—a freckled truce with her father’s wide nose and her mother’s brown eyes.

But then her father opened the front door and light flooded the room so quickly that Misty and her mother winced against it. Misty’s father turned to say something else until he spotted Misty sitting on the floor at the end of the narrow hallway. He stopped.

Her parents stared at her and Misty stared back at them.

This was usually the part where they would stop fighting. Her mother’s voice would lift to a false high, her father hugging Misty even though he rarely showed affection. Even their attempts at happiness felt wrong.

But this time Misty’s father looked away from her without smiling. He looked at her mother and said, “This is what you wanted, Beth. You’re the one who has to tell them,” then slammed the door hard enough to rattle the glass in the windows.

Misty’s mother stood with her arms crossed over her chest. She stared not at Misty but through her to some far and foggy place that Misty had never seen. She went there often enough that Misty knew how to handle it, how to be patient, to wait for her mother to come back to herself. Back to Misty. But this time, her mother touched her fingers to her mouth, walked back across the trailer, and disappeared into her bedroom.

The trailer was quiet without her parents’ noise. There were so many small and empty spaces in need of filling.

Misty dug her heels into the carpet one last time. She pressed her full weight against her bedroom door so fast that her sister didn’t have time to prepare. Something thudded behind her and the door jerked back a few inches, the dark space of their room yawning by Misty’s side until her sister growled and pushed back even harder. Misty’s feet burned as she lurched across the carpet, and she fell to the floor on the outside of everything she wanted.

Two

After Misty cried and the tears dried on her cheeks and left her skin feeling tacky and brittle, after it was obvious that neither her mother nor her sister were coming to check on her, Misty walked through the same door where her father had left. Her body carried her to the creek by muscle memory, back to the place she always went when she was sad or lonely.

She climbed down the steep embankment before the creek using a chain that was sunk into the ground with concrete. The chain was old and thick and rusted. Her mother told her it had been part of a swinging bridge once that spanned the width of the creek and connected this ground to the road above. It used to be the only way to get to their holler until the new bridge had been built. Earl had the swinging bridge torn down when he bought the land and cleared the trees to make room for his trailers. It always made Misty sad to see the chain all by itself, torn away from what it used to be.

She stood with her toes on the edge of the place where the sand gave way to the water. The sun was warm on her shoulders, but she didn’t feel warmed by it. She rolled the hem of her shorts up until the denim cut into her thighs and walked barefoot into the water, careful for broken glass that sometimes shifted loose from the sand and craved something soft to tear into.

The water inched higher as she walked, wetting ankle, shin, and knee. It settled at her midthigh, just below the line of her shorts as Misty stood in the deepest part of the creek. She waited, listening for the slam of a screen door or the call of her mother. When nothing came for her, Misty bent at the waist until her back was parallel to the water. She closed her eyes.

Beneath her were minnows and crawdads and tadpoles. There were copperheads and cottonmouths slicking along the grass on the bank. There were bluegill not far away, small for their age because the creek was a small place and it was hard for any creature to outgrow its home. The fish stayed small because they had no room to get bigger, and because they were small, there was always just enough to go around—enough food, enough light, enough water—and they all got to go on living, if not growing.

But it was the crawdads that Misty came for, the crawdads that kept her coming back. They seemed small and murky brown at first, but up close the crawdads were a wash of colors, their arms stained woodsmoke blue with a muddy green along their eight trembling legs, their backs speckled with small dots the color of old lace, a yellow that still remembered what it felt like to be white. They were small enough to fit inside Misty’s palm. Most of them four or five inches long with thin legs and two large claws at the end, which always seemed to be opening and closing, always searching for something to hold on to.

Misty spoke to the crawdads as she stood in the creek, though she never opened her mouth. Some words weren’t made for speaking, not by tongues like hers, so small and flat. So she called out from inside herself instead.

It was easy. Her mother had taught her how to pray when she was five years old. She knelt beside Misty on the threadbare carpet and said, “Now open up your heart. It’s more listening than saying anything, but you can ask for things, too. You open up and wait for God to speak to you. Close your eyes now. Close your eyes.” So Misty listened to her mother and she listened for God—her chest a door flung wide open; her heart the golden light spilling onto the floor, eating the darkness whole. She invited everything inside.

But instead of God, Misty heard the mouse living in the walls of their trailer.

The mouse showed Misty the tangled nest she’d made for her children from the torn scraps of the science folder Penny had lost the week before. The mouse filled Misty’s nose with the scent of mothballs and her bones with the hum of the pipes in the walls. The mouse showed Misty what it felt like to be a mouse, furred and quick and small.

Eventually, with practice, Misty got better at reaching out to the world. She learned that everything had a name. Not the name that most people knew them by, but something different, an underneath name made of sounds and memories and feelings, a name that shifted and grew and evolved. Some things had many names, and some had only one. Some things had names that she couldn’t speak inside herself, they were so long with age, so heavy with time.

Misty had a name, too, that lived beneath and beside her other name all the time, and this name was long and twisting, filled with memory and sound. She could choose parts of her name, selecting the memories or moments she held closest, but other parts were beyond her control. The crawdads had tried to explain it to her once—how names were made from things remembered and lost, things passed down from generations before, and things that the body knew that the mind forgot. Sometimes she understood how names worked, but sometimes she still wasn’t sure.

But she knew that in order to speak to the world, she had to offer her name, like holding out her hand, one half of a bridge built between her and everything else. The crawdads could respond with their name and join Misty, sharing thoughts and memories and feelings. Misty knew what it felt like to be small and clawed and slick. She knew the safest places to hide during squalls when the creek swelled with water and the current threatened to tear the crawdads away. She had seen the pictures the crawdads etched into the sand with their tails in the deepest parts of the creek, messages like prayers that the minnows carried downstream. She could smell an oil spill in an eddy and she had felt the weight of eggs gathered on her belly and she had molted with the crawdads a hundred, hundred times. And she knew all of this because the crawdads knew and they shared it with her. They shared themselves.

Misty conjured her name as she stood in the creek with her nose hovering inches above the cool water. The name bubbled inside of her, dozens of images and feelings connected by the thinnest of strands—her hand reaching out for her grandmother’s when Misty was barely old enough to walk, the paper-thin feeling of the older woman’s skin inside Misty’s palm; the rattle of her mother’s breathing when she and Misty were both sick and her mother carried Misty from room to room, rocking her, shushing her, begging her to sleep; the first time Misty had ever tasted snow, bright and shivering cold; her father’s voice from a different room, muffled and rumbling; a doe in the woods, blood on its hip and pain in Misty’s leg, pain in her chest; Penny standing beside her in church and singing along to a song she didn’t know, making up the words until Misty’s sides ached from trying not to laugh; the feeling of a crawdad skittering over her shoulder, tangling in her hair; her mother sitting on the couch with her head in her hands; her father’s truck peeling out of the driveway, gravel pinging against the metal sides of the trailer; her mother’s arms crossed over her chest that morning, the faraway look in her eyes, a feeling of sadness like many small stones stacked inside her stomach, weighing Misty down, down, down.

Misty’s chest ached with the memories and she almost pulled away, almost ended her name before it ended itself, but she held on. Names were honest things. They didn’t hide. They didn’t lie. They couldn’t, as far as Misty knew, and the only way to speak to the world was to be true.

But it was getting harder to be honest with the world as her name gathered sadness and heartache and weight. Her name growing heavier by the day.

Then the crawdads answered with their name—a stirring in the dark, a rustling, deep-blue something. The crawdads were silt running between her fingers, the hushed crinkle of a morning glory closing its petals for the day, the pop of a bone from its socket, and they were there, in Misty’s head, in her chest, in her legs. They shared her body with her and they helped her carry the weight of her thoughts, her memories.

“Come see me,” she said.

And though she only meant to speak to the crawdads, the light Misty shone into the world attracted all sorts of things and they called out to her with their own voices.

A black snake shared the crunch of a field mouse’s neck, a bright bubble of blood bursting in the center of Misty’s chest.

The minnows shone silver flashes against the backs of her eyes, and the force of the water against their scales as they swam against the current, the dim green taste of the deepest water filled her mouth until her tongue was mossy and thick.

Her fingers spasmed with the flutter of a bluegill’s tail a few feet away.

But it wasn’t just Misty that got a sense of the other creatures’ bodies; they got a sense of hers, too. They were always shocked at first. She knew them as a little weight that perched along her spine, looking up at her like someone walking into a cavern and finding that it was a cathedral. They marveled at the space of her, the strange proportions of her body. They rocked with the rhythm of her lungs and curled against the hollow of her clavicle, but all of them eventually settled in her legs. They begged her to walk, to carry them a while. They asked her to wiggle her toes, to jump, to kneel. They crowded in her joints, their minds like a hive of bees, their excitement pumping Misty’s heart faster, faster. They’d never felt anything like her before, never known a body so small but so great at the same time, and they filled Misty, however briefly, with a love of herself as a strange thing, marvelous and new.

And though she couldn’t see it with her eyes closed, all around her, a circle formed. All manner of things that lived in the creek swam closer. The air itself rippled with a faint heat as Misty called the crawdads near. Even the birds felt a certain pull, a shift in the wind that drew them to the trees that lined the creek, and they looked down with small, black eyes at the little girl standing below.

The crawdads hurried through the water and grabbed hold of the bend in Misty’s knees, pulled themselves up in pinches and stutters. They clung to the hem of her shorts and crawled over one another’s backs, grasping for purchase.

Misty opened her eyes and ended her call. She swayed to the side, part of her still convinced she was the water. She took a deep breath and wiggled her fingers. She pressed her tongue against the roof of her mouth and swallowed just to feel the muscles in her throat contract. The door inside her chest was heavier now, harder to close, and a little piece of her remained open as she straightened her back and waited for the dizziness to pass.

It was hard to share her body with something like the creek that believed absolutely the truth of its existence when she didn’t believe the same of herself. It was hard to convince her body to return to her when it longed to be clawed and slick or hard and slithering or winged and feathered and gone, gone, gone.

But it was a girl body instead.

It was small and pale-skinned and freckled with squat calves that were bruised from falling. It was a here-and-now body with a sore spot on her tongue from eating corn bread straight out of the oven last night and an ache behind her eyes from crying that morning. It was still a short body, a good-at-hiding body that fit into the dark corner by her parents’ bedroom door and listened to the things they said to each other when they thought no one was listening. Dark-haired and dark-eyed and at least three inches shorter than she wanted it to be, it was her body and it was impossible to ignore.

Misty stood up slowly and walked even more slowly in the direction she had come. The crawdads clung to the sleeves of her T-shirt. They tangled themselves inside her hair and swayed with her as she walked through the water. Her body felt wrung out, emptied of everything she had brought—every need, every worry, every fear. When she reached the creek bank, she dropped to her knees on the soft sand. She rested her forehead against the ground and closed her eyes. She heard, in the distance, the familiar grind of her mother’s car engine. Misty was supposed to go grocery shopping with her this time since it was Misty’s turn to pick out the ice cream, but the tires crunched over the driveway and were gone without her. A pang of sadness rippled through Misty and the crawdads felt it, too, as they fell from Misty’s clothes one at a time. They gathered around her, worried. They searched for wounds on her body, murmuring back and forth, and the sound of their shared conversation was like leaves crunching inside her head.

“I’m okay,” Misty said as the crawdads worked at the hem of her T-shirt, trying to find a way beneath.

They didn’t believe her. They shared images of small things—acorns and newly laid eggs and the round blue pebbles buried beneath the creek bed. This was how the crawdads, how everything, spoke to her. Not with language that she understood, but with a mix of images and sensations that Misty translated. Sometimes it was hard to interpret what the crawdads meant, and even harder to make herself clear to them. But Misty knew what they meant when they shared these images with her. They were telling her that Misty was like the acorn, the egg, the pebbles. She felt small that day, and the crawdads wanted to know why.

Misty turned her head so she could see a half dozen of the crawdads keeping watch over her. “I’m just tired. I don’t want to go back home.”

And at once the sensation of fifteen small hands holding her in place, asking her to stay.

“I can’t.” Misty held out a finger and the crawdads crowded around it, touching the tips of their claws to her skin. “I have to go back. My bed is there. And my mom. She’d be sad without me.”

The crawdads sent her a fuzzy feeling in her lips and the image of a night sky, which had always been their way of asking why or telling her that they didn’t understand.

Misty sighed. “I don’t know. I don’t think my family is happy.” She shared a rush of images. Her mother standing by the front door with her head in her hands. A window in an empty house that they passed every Sunday on the way to church that made Misty feel lonely. Penny slamming a door in her face. The little lines of light that etched across her favorite quilt when she hid beneath it, the light tracing the seams, the light pointing out all the places that were worn and frayed and falling apart.

The crawdads gathered nearer.

“I wish I could talk to them like I talk to you,” Misty said. “They don’t listen to me much when I do talk, but if I was in their heads, then they couldn’t ignore me.”

Misty laid her cheek against the sand. She’d thought of telling her family about how she could speak to the world but she wasn’t sure how they’d react. They might not believe her at all. She had no way to explain what she did, no proof besides a few crawdads crawling over her skin. Or worse, if they believed her, they might also believe she was bad. Her aunt Jem told stories sometimes about strange people and strange things that had happened in their family, and Misty’s mother hated the stories. She never wanted to listen. If she found out that Misty was a strange thing, too, then she might hate her or turn her away, might never trust her again.

After a while, some of the crawdads returned to the creek. Some started to burrow beneath the ground, digging narrow tunnels where they could hide, until only one crawdad remained before her. It was almost impossible to tell them apart, and even if she could, it was impossible to give the crawdads names of their own. She had tried before, but the crawdads rejected them. They knew themselves as crawdad and nothing else. They were a collective, a group. When she called, they answered together, and when they left, they left together. They didn’t want to be known apart.

A crawdad returned from the creek with a shed crawdad skin in its claws. The crawdads had shared their memories of molting with Misty, the way they shed their old bodies so they could keep growing. She’d felt the itch of a too-tight skin, the fevered panic of shedding, the need to be released. She knew what it was like to expand, to grow, and she loved to look at the shed skins, to touch them, gently, and feel the way they gave beneath her, like she was holding light inside her hands. The crawdads shared them with her, and Misty collected them in a box under her bed. Looking at them made her feel steady, like there was nothing in the world that couldn’t be undone or redone.

Misty stroked her finger along the back of the molted skin. It was only partially intact—the tail and one claw had been torn away, leaving a fragment of the crawdad who had shed its body. A bell chimed nearby and Misty jumped. She kicked her feet out of the water and scrambled to her knees. She’d hung a string of bells in the bushes weeks before to warn her when someone came too close. The only person who came looking for her these days was her neighbor, William. She hadn’t known him before they moved into Earl’s trailer, but now he was the closest thing to a best friend that Misty had ever had. He was the same age as her, but a grade behind because he’d missed too much school last year. William could tie knots and spit, and he cursed when no one was around to hear. He listened to her when she complained about Penny and he was nice enough, but she didn’t trust him with her crawdads. His BB gun had been taken away for shooting at robins from his back porch. Without the gun, she worried he might turn his attention on the crawdads. They were so easy to corner, to catch.

So Misty pounded her fist against the ground three times. With every blow, a jolt shot through the air, something like a shout, like thunder. The crawdads skittered back to the creek or crawled into their burrows. As William crashed through the underbrush on the hill above the creek, the last crawdad’s tail swished into the water and disappeared.

“Hey!” he called. “What’re you doing?”

“Playing,” Misty said.

“Is them your bells back there?”

She nodded. “That’s my alarm.”

“That’s pretty smart,” he said. “Have you thought about adding something? Like some spikes. Or maybe digging a pit or something for people to fall into. The bells is good but they won’t stop nobody from coming down here.”

“It ain’t supposed to stop nobody. It’s just got to tell me they’re coming.”

William shrugged. “Let me know if you change your mind. I could draw something up for you and show you how it’d work. If you’re interested.”

“Yeah,” Misty said. “What’re you doing anyway?”

William smiled. “Going to the barn. All of us are.”

“Who’s us?” Misty asked.

“Me and Penny and you.”

“Why?”

He grinned. “I got a game for us to play.”

“What kind?”

“You have to come and see. I bet you ain’t never played it before though.”

“What is it?”

William turned and ran through the high weeds without answering. He sent the bells ringing again, louder this time than before, and Misty felt the pluck of his fingers against the string inside her chest, her own ribs fluttering with the sound.

She dipped her hand into the creek before she left, searching for any crawdads that might have lingered. The slow current altered the image of her hand, making it appear as though her finger crooked away at the knuckle, like somewhere beneath the surface of the water her hand was broken and she just hadn’t felt the pain yet.

Excerpted from Every Bone a Prayer, copyright © 2020 by Ashley Blooms