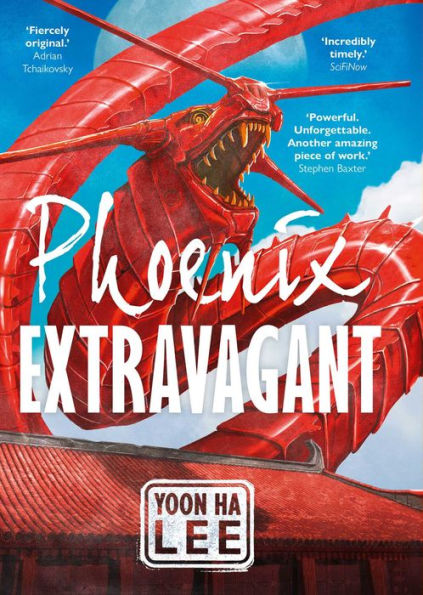

We’re excited to share an excerpt from Phoenix Extravagant, the new blockbuster original fantasy work from Nebula, Hugo, and Clarke Award-nominated author Yoon Ha Lee—publishing October 20th with Solaris.

Gyen Jebi isn’t a fighter or a subversive. They just want to paint.

One day they’re jobless and desperate; the next, Jebi finds themself recruited by the Ministry of Armor to paint the mystical sigils that animate the occupying government’s automaton soldiers.

But when Jebi discovers the depths of the Razanei government’s horrifying crimes—and the awful source of the magical pigments they use—they find they can no longer stay out of politics.

What they can do is steal Arazi, the ministry’s mighty dragon automaton, and find a way to fight…

The electrical light had a chilly aspect, without the warmth of sunlight. And it didn’t bring any significant heat with it. The air here was uncomfortably cold, although not as bad as the outdoors, and dry in comparison with today’s damp. Like a cave, probably, if Jebi had known anything about caves but what they’d heard in stories about bandits’ hideouts and tiger-sages’ lairs.

“There’s an elevator,” Hafanden added, as though the stairs inconvenienced Jebi more than himself, “but it’s used for freight, and the security precautions are a hassle. Besides, I wanted to mention a few things to you before we meet Vei and Arazi.”

Arazi, Jebi thought, mentally translating the name: storm. An inauspicious name by Hwagugin standards. But who could say how a Razanei thought of it?

“You may be having qualms about helping your conquerors,” Hafanden said. “I wish to assure you that your work will be an act of the highest patriotism.”

Besides the fact that this was an uncomfortable topic even among friends, Jebi had to suppress an incredulous laugh. Patriotism? For Razan, presumably, since they couldn’t see how this benefited Hwaguk. Especially if they were going to be helping create more automata for the patrols in the streets.

Buy the Book

Phoenix Extravagant

“I can’t see your expression,” Hafanden said with a half-sigh—he was still in the front—“but I can imagine you’re skeptical. Let me put it this way, then. Disorder does no one any favors, Hwagugin or Razanei.”

Jebi made an involuntary noise, and Hafanden slowed, turning back toward them.

“I prefer not to use the term ‘Fourteener,’” he said. “Your people have an identity of their own, one that is valuable in its own right. You have your doubts, and you’re not entirely wrong, but—look at it this way. You’ve seen the encroachment of Western arts, Western books, Western ideas.”

Jebi shrugged.

“We can only stand against that encroachment,” Hafanden said, with a fervor that surprised them, “if we stand together. The means may be regrettable, but the cause justifies it.”

“I’m not political,” Jebi said, trying to devise a tactful way out of this topic. For all they cared, Hwaguk had been doing just fine by forbidding Western traders and diplomats and philosophers from entering the country. They couldn’t deny, however, that it hadn’t taken long for their people to adopt Western technologies and comforts, like electrical lighting and automobiles. Those who could afford them, anyway.

“Forgive me,” Hafanden said, inclining his head. “The truth is, you don’t need to be, not for your role. But I always feel that my people work better if they understand the Ministry’s mission.”

Jebi shuddered inwardly at the matter-of-fact possessiveness of my people. Maybe they should have read more carefully before they signed all those papers. Not that it would have made any difference. They’d still be here, and Bongsunga was still a hostage for their good behavior.

They arrived at last several levels down. Jebi had lost track of the number of stairs, and they cursed themself for not keeping count. They passed more guards, again in the common pattern for the Ministry: two humans accompanied by two automata.

I should keep track of the patterns on the automata’s masks, Jebi thought halfway down the hallway, after they’d left the automata behind. Rattled as they were, they couldn’t bring the image to mind. They’d have to do better in the future. Of course, they might soon know more about the masks than they wanted to.

Next came a hallway that meandered at uncomfortable angles for which Jebi could see no logic, and which gave them a nagging headache when they tried to examine them too closely. Doors opened off the hallway to either side, not the sliding doors that were common to Hwagugin and Razanei wooden buildings, but hinged, with numbered metal plaques, no names or words.

The end of the hallway led to double doors of metal, and more guards. Jebi had the inane desire to strike up a conversation with one of the humans, ask them about their favorite novel or what they ate for lunch, anything to ease the dungeon-like atmosphere of the underground complex. But they knew better than to do so in front of Hafanden.

The guards parted for Hafanden, giving Jebi a clear view of the snaking symbols etched into the doors. A colored enamel of some sort filled the symbols. Jebi thought at first that it was purple or brown, but it more closely resembled the murky colors of a new bruise. Trying to memorize the shapes only worsened their headache.

Hafanden pressed his hand directly against a bare section of the left door, then the right. The doors opened silently, and he passed the threshold. After a worried pause, Jebi hurried after him.

They both emerged into an immense cavern, its planes and hard angles betraying its artificial origins. The sight of all that space was so disorienting that Jebi tripped over their own feet. Hafanden reached out just long enough to steady them, and Jebi blurted out a mortified thank-you. As much as they disliked the liberty, they didn’t want to fall flat on their face, either.

Several people stood at the cavern’s edges. All of them wore gray and white with the particular black armbands that singled them out as belonging to Armor. Jebi couldn’t tell what, if anything, they were doing. Perhaps only watching.

The light here differed from the cold, clear radiance out in the stairwell and the hallways. For one thing, it had no visible source. And it had a peculiar sea-torn quality, as though it had passed through turbulent water. Jebi had known something like it during their childhood, before their mother had died: she’d taken them and Bongsunga to the nearest lake, a journey of four days out of the capital. Jebi had fretted about bandits, all the while secretly longing to be kidnapped by some so they could have an adventure. Bongsunga assured them that bandits stayed away from well-traveled roads, spoiling the fun. In their mind’s eye, the ocean was like that lake, but bigger in all directions, and wilder too.

What made the breath stick in Jebi’s throat, however, was not the light, or even the harsh cold whisper of air circulating through unfathomable passages, but the dragon.

They’d only seen automata in human form, had assumed that was the only kind. It should have occurred to them that, just as a sculptor could hew bear or badger from the same piece of jade, the artificers could create automata in whatever shape they pleased. Metal was malleable, after all.

Jebi had drawn dragon-horses, a common good-luck motif in folk art, with their smoky manes and talons. But the mechanical dragon that dominated the cavern, three times Jebi’s height at the withers, didn’t resemble a horse, not in motion. The wedge-shaped head, adorned by a mask of painted wood, was surrounded by a frill of wire coils and gutting spikes. Phoenix-colored light burned behind the eye holes of the mask, like fire and fire’s yearning. Serpentine articulations gave it the look of a suit of armor gone wrong, grown beyond any hope of taming, and its great tail ended in four wicked spikes. It rippled in a circular path, or something that would have been a circle if geometry admitted such subtly wrong curves. Only then did Jebi see the chains, which struck melodies of restraint, a percussion of imprisonment, against the glassine rock floor.

The dragon was too tall to be contained by any ordinary fence, and for whatever reason, its keepers had declined to put it in a cage. Admittedly, constructing a large enough cage would have been a nontrivial proposition. But someone had painted a circle on the cavern floor in virulent green paint. Jebi guessed that one wasn’t supposed to cross the circle.

“Arazi,” Hafanden said.

The movement stopped. The dragon stood like a predatory statue, one forelimb poised as though to strike despite the chains.

Storm, Jebi thought again. A fitting name for a dragon, now that they knew.

Excerpted from Phoenix Extravagant, copyright © 2020 by Yoon Ha Lee.