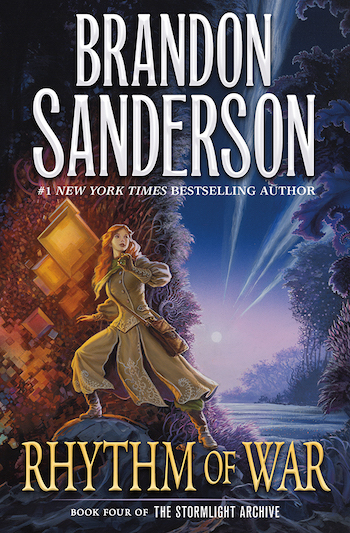

On November 17, 2020, The Stormlight Archive saga continues in Rhythm of War, the eagerly awaited fourth volume in Brandon Sanderson’s #1 New York Times bestselling fantasy series.

Tor.com is serializing the new book from now until release date! A new installment will go live every Tuesday at 9 AM ET.

Every chapter is collected here in the Rhythm of War index. Listen to the audiobook version of this chapter below the text, or go here for the full playlist.

Once you’re done reading, join our resident Cosmere experts for commentary on what this week’s chapter has revealed!

Want to catch up on The Stormlight Archive? Check out our Explaining The Stormlight Archive series!

Chapter 15

The Light and the Music

Logicspren react curiously to imprisonment. Unlike other spren, they do not manifest some attribute—you cannot use them to make heat, or to warn of nearby danger, or conjoin gemstones. For years, artifabrians considered them useless—indeed, experimenting with them was uncommon, since logicspren are rare and difficult to capture.

A breakthrough has come in discovering that logicspren will vary the light they radiate based on certain stimuli. For example, if you make the Light leak from the gemstone at a controlled rate, the spren will alternate dimming and brightening in a regular pattern. This has led to fabrial clocks.

When the gemstone is tapped with certain metals, the light will also change states from bright to dim. This is leading to some very interesting and complex mechanisms.

—Lecture on fabrial mechanics presented by Navani Kholin to the coalition of monarchs, Urithiru, Jesevan, 1175

In the weeks following the assault on Hearthstone, Kaladin’s anxiety began to subside, and he pushed through the worst of the darkness. He always emerged on the other side. Why was that so difficult to remember while in the middle of it?

He’d been given time to decide what to do after his “retirement,” so he didn’t rush the decision, and didn’t tell anyone other than Adolin. He wanted to find the best way to introduce the idea to his Windrunners—and if he could, make his decisions first. Better to bring them a clear plan.

He found himself understanding Dalinar’s order more and more as the days passed. At least Kaladin didn’t have to keep pretending he wasn’t exhausted. He did delay his decision though. So Dalinar eventually gave him a gentle—but firm—nudge. Kaladin could have a little more time to decide his path, but they needed to start promoting other Windrunners to take over his duties.

So it was that ten days after the mission to Hearthstone, Kaladin stood in front of the army’s command staff and listened to Dalinar announce that Kaladin’s role in the army was “evolving.”

Kaladin found the experience humiliating. Everyone applauded his heroism even as he was forced out. Kaladin announced that Sigzil—with whom he’d conferred earlier in the day—would take over daily administration of the Windrunners, overseeing things like supplies and recruitment. He’d be named to the rank of companylord. Skar, when he returned from leave at the Horneater Peaks, would be named company second, and would oversee and lead active Windrunner missions.

A short time later, Kaladin was allowed to go—fortunately, there was no forced “party” for him. He retreated down a long dark hallway in Urithiru, relieved that he didn’t feel nearly as bad as he had worried he would. He wasn’t a danger to himself today.

Now he just had to find new purpose in life. Storms, that scared him—having nothing to do reminded him of being a bridgeman. When he wasn’t on bridge runs, those days had stretched. Full of blank space that numbed the mind, a strange mental anesthetic. His life was far better now. He wasn’t so lost in self-pity that he couldn’t notice or acknowledge that. Still, he found the similarity uncomfortable.

Syl hovered in front of him in the Urithiru hallway, taking the form of a fanciful ship—only with sails on the bottom. “What is that?” Kaladin asked her.

“I don’t know,” she said, sailing past him. “Navani was drawing it during a meeting a few weeks ago. I think she got mixed up. Maybe she hasn’t seen boats before?”

“I sincerely doubt that’s the case,” Kaladin said, looking down the hallway. Nothing to do.

No, he thought. You can’t pretend you have nothing to do because you’re scared. Find a new purpose.

He took a deep breath, then strode forward. He could at least act confident. Hav’s first rule of leadership, drilled into Kaladin on his first day as a squadleader. Once you make a decision, commit to it.

“Where are we going?” Syl asked, transforming into a ribbon of light to catch up to him.

“Sparring grounds.”

“Going to try some training to take your mind off things?”

“No,” Kaladin said. “I’m going to—against my better judgment—seek wisdom there.”

“Many of the ardents who train there seem pretty wise to me,” she said. “After all, they shave their heads.”

“They…” Kaladin frowned. “Syl, what does that have to do with being wise?”

“Hair is gross. It seems smart to shave it off.”

“You have hair.”

“I do not; I just have me. Think about it, Kaladin. Everything else that comes out of your body you dispose of quickly and quietly—but this strange stuff oozes out of little holes in your head, and you let it sit there? Gross.”

“Not all of us have the luxury of being fragments of divinity.”

“Actually, everything is a fragment of divinities. We’re relatives that way.” She zipped in closer to him. “You humans are merely the weird relatives that live out in the stormshelter; the ones we try not to let visitors know about.”

Kaladin could smell the sparring grounds before he arrived—the mingled familiar scents of sweat and sword oil. Syl shot to the left, making a loop of the room as Kaladin hurried past shouting pairs of men engaged in bouts of all types. He made his way to the rear wall where the swordmasters congregated.

He’d always found martial ardents to be a strange bunch. Ordinary ardents made more sense: they joined the church for scholarly reasons, or because of family pressure, or because they were devout and wanted to serve the Almighty. Most martial ardents had different pasts. Many had once been soldiers, then given themselves over to the church. Not to serve, but to escape. He’d never really understood what might lead someone to walk that path. Not until recently.

As he walked among the training soldiers, he was reminded why he’d stopped coming. Bowing, murmurs of “Stormblessed,” people making way for him. That was fine in the hallways, when he passed people who didn’t know him. But the ones who trained here were his brothers—and in some few cases sisters—in arms. They should know he didn’t need such attention.

He reached the swordmasters—but unfortunately, the man he sought wasn’t among them. Master Lahar explained that Zahel was on laundry detail, which surprised Kaladin. Though he knew all ardents took turns on service detail, he wouldn’t have thought a swordmaster would be sent to wash clothing.

As he left the sparring chamber, Syl came soaring back to him, wearing the shape of an arrow in flight. “Did I hear you asking for Zahel?” she asked.

“You did. Why?”

“It’s just that… there are several swordmasters, Kaladin. A few of them are actually useful. So why would you want to talk to Zahel?”

He wasn’t certain he could explain. One of the other swordmasters—or likely any of the ardents who frequented the sparring grounds—could indeed answer his questions. But they, like the others, regarded Kaladin with an air of respect and awe. He wanted to talk to someone who would be completely honest with him.

He made his way out to the edge of the tower. Here, open to the sky, various tiered discs of stone projected from the base of the structure like enormous fronds. Over the last year, a number of these had been turned into pastures for chulls, lobberbeasts, or horses. Others were hung with lines for drying wash. Kaladin started toward the drying wash, but paused—then decided to make a short detour.

Navani and her scholars claimed that these outer plates around the tower had once been fields. How could that ever have been the case? The air up here was cold, and though Rock seemed to find it invigorating, Kaladin could tell it lacked something. He grew winded more quickly, and if he exerted himself, he sometimes felt light-headed in ways he never did at normal elevations.

Highstorms hit here infrequently. Nine out of ten didn’t get high enough—passing as an angry expanse below, rumbling their discontent with flashes of lightning. Without the storms, there simply wasn’t enough water for crops, let alone proper hillsides for planting polyps.

Still, at Navani’s urging, the last six months had involved a unique project. For years the Alethi had fought the Parshendi over gemhearts on the Shattered Plains. It had been a bloody affair built upon the corpses of bridgemen whose bodies—more than their tools—spanned the gaps between plateaus. It shocked Kaladin that so many involved in this slaughter had missed asking a specific and poignant question:

Why had the Parshendi wanted gemstones?

To the Alethi, gemstones were not merely wealth, but power. With a Soulcaster, emeralds meant food—highly portable sources of nutrition that could travel with an army. The Alethi military had used the advantage of mobile forces without long supply lines to ravage across Roshar during the reigns of a half dozen interchangeable kings.

The Parshendi hadn’t possessed Soulcasters though. Rlain had confirmed this fact. And then he’d given humankind a gift.

Kaladin walked down a set of stone steps to where a group of farmers worked a test field. The flat stone had been spread with seed paste—and that had grown rockbuds. Water was brought from a nearby pump, and Kaladin passed bearers lugging bucket after bucket to dump on the polyps and simulate a rainstorm.

Their best farmers had explained it wouldn’t work. You could simulate the highstorm minerals the plants needed to form shells, but the cold air would stifle growth. Rlain had agreed this was true… unless you had an edge.

Unless you grew the plants by the light of gemstones.

The common field before Kaladin was adorned with a most uncommon sight: enormous emeralds harvested from the hearts of chasmfiends, ensconced within short iron lampposts that were in turn bolted to the stone ground. The emeralds were so large, and so full of Stormlight, that looking at one left spots on Kaladin’s vision, though it was in full daylight.

Beside each lantern sat an ardent with a drum, softly banging a specific rhythm. This was the secret. People would have noticed if gemstone light made plants grow—but the mixture of the light and the music changed something. Lifespren—little green motes that bobbed in the air—spun around the drummers. The spren glowed brighter than usual, as if the Light of the gemstones was infusing them. And they’d move off to the plants, spinning around them.

This drained the Light, like using a fabrial did. Indeed, the gemstones would periodically crack, as also happened to fabrials. Somehow, the mixture of spren, music, and Light created a kind of organic machine that sustained plants via Stormlight.

Rlain, wearing his Bridge Four uniform, walked among the stations, checking the rhythms for accuracy. He usually wore warform these days, though he’d confessed to Kaladin that he disliked how it made him seem more like the invaders, with their wicked carapace armor. That made some humans distrust him. But workform made people treat him like a parshman. He hated that even more.

Though to be honest, it was odd to see Rlain—with his black and red marbled skin—giving direction to Alethi. It was reminiscent of what was happening in Alethkar, with the invasion. Rlain didn’t like it when people made those kinds of comparisons, and Kaladin tried not to think that way.

Regardless, Rlain seemed to have found purpose in this work. Enough purpose that Kaladin almost left him and continued on his previous task. But no—the days where Kaladin could directly look out for the men and women of Bridge Four were coming to an end. He wanted to see them cared for.

He jogged through the field. While any one of these head-size rockbuds would have been considered too small to be worth much in Hearthstone, they were at least big enough that there would be grain inside. The technique was helping.

“Rlain,” Kaladin called. “Rlain!”

“Sir?” the listener asked, turning and smiling. He hummed a peppy tune as he jogged over. “How was the meeting?”

Kaladin hesitated. Should he say it? Or wait? “It had some interesting developments. Promotions for Skar and Sigzil.” Kaladin scanned the field. “But someone can fill you in on that later. For now, these crops are looking good.”

“The spren don’t come as readily for humans as they did for the listeners,” he said, surveying the field. “You cannot hear the rhythms. And I can’t get humans to sing the pure tones of Roshar. A few are getting closer though. I’m encouraged.” He shook his head. “Anyway, what was it you wanted, sir?”

“I found you an honorspren.”

Kaladin was accustomed to seeing an unreadable, stoic expression on Rlain’s marbled face. That melted away like sand before a storm as Rlain adopted a wide, face-splitting grin. He grabbed Kaladin by the shoulders, his eyes dancing—and when he hummed, the exultant rhythm to it almost made Kaladin feel he could sense something beyond. A sound as bombastic as sunlight, as joyful as child’s laughter.

“An honorspren?” Rlain said. “Who is willing to bond with a listener? Truly?”

“Vratim’s old spren, Yunfah. He was delaying choosing someone new, so Syl and I gave him an ultimatum: Choose you or leave. This morning, he came to me and agreed to try to bond with you.”

Rlain’s humming softened.

“It was a gamble,” Kaladin said. “Since I didn’t want to drive him away. But we finally got him to agree. He’ll keep his word; but be careful. I get the sense he’ll take any chance he can to wiggle out of the deal.”

Rlain squeezed Kaladin on the shoulder and nodded to him, a sign of obvious respect. Which made the next words he spoke so odd. “Thank you, sir. Please tell the spren he can seek elsewhere. I won’t be requiring his bond.”

He let go, but Kaladin caught his arm.

“Rlain?” Kaladin said. “What are you saying? Syl and I worked hard to find you a spren.”

“I appreciate that, sir.”

“I know you feel left out. I know how hard it is to see the others fly while you walk. This is your chance.”

“Would you take a spren who was forced into the deal, Kaladin?” Rlain asked.

“Considering the circumstances, I’d take what I could get.”

“The circumstances…” Rlain said, holding up his hand, inspecting the pattern of his skin. “Did I ever tell you, sir, how I ended up in a bridge crew?”

Kaladin shook his head slowly.

“I answered a question,” Rlain said. “My owner was a mid-dahn lighteyes—nobody you’d know. An overseer among Sadeas’s quartermasters. He called out to his wife for help as he was trying to add figures in his head, and—not thinking—I gave him the answer.” Rlain hummed a soft rhythm, mocking in tone. “A stupid mistake. I’d been embedded among the Alethi for years, but I grew careless.

“Over the next few days, my owner watched me. I thought I’d given myself away. But no… he didn’t suspect I was a spy. He just thought I was too smart. A clever parshman frightened him. So he offered me up to the bridge crews.” Rlain glanced back at Kaladin. “Wouldn’t want a parshman like that breeding, now would we? Who knows what kind of trouble they would make if they started thinking for themselves?”

“I’m not trying to tell you that you shouldn’t think, Rlain,” Kaladin said. “I’m trying to help.”

“I know you are, sir. But I have no interest in taking ‘what I can get.’ And I don’t think you should force a spren into a bond. It will make for a bad precedent, sir.” He hummed a different rhythm. “You all name me a squire, but I can’t draw Stormlight like the rest. There’s a wedge between me and the Stormfather, I think. Strange. I expected prejudice from humans, but not from him… Anyway, I will wait for a spren who will bond me for who I am—and the honor I represent.” He gave Kaladin a Bridge Four salute, tapping his wrists together, then turned to continue teaching songs to farmers.

Kaladin trailed away toward the washing grounds. He could see the man’s point, but to pass up this chance? Maybe the only way to get what Rlain wanted—respect from a spren—was to start with one who was skeptical. And Kaladin hadn’t forced Yunfah. Kaladin had given an order. Sometimes, soldiers had to serve in positions they didn’t want.

Kaladin hated feeling he’d somehow done something shameful, despite his best intentions. Couldn’t Rlain accept the work he’d put into this effort, then do what he asked?

Or maybe, another part of him thought, you could do what you promised him—and listen for once.

Kaladin entered the washing field, passing lines of women standing at troughs as if in formation, warring with an unending horde of stained shirts and uniform coats. He trailed around the ancient pump, which bled water into the troughs, and through a rippling field of sheets hung on lines like pale white banners.

He found Zahel at the edge of the plateau. This section of the field overlooked a steep drop-off. In the near distance, Kaladin could see Navani’s large construction hanging from the plateau—the device used to raise and lower the Fourth Bridge.

It seemed like falling from here would leave one to fall for eternity. Though he knew the mountain must slope down there somewhere, clouds often obscured the drop. He preferred to think of Urithiru as if it were floating, separated from the rest of the world and the agonies it suffered.

Here, at the outermost of the drying lines, Zahel was carefully hanging up a series of brightly colored scarves. Which lighteyes had pressed him into laundering those? They seemed the sort of frivolous neckpieces the more lavish among the elite used to accent their finery.

In contrast to the fine silk, Zahel was like the pelt of some freshly killed mink. His breechtree cotton robe was old and worn, his beard untamed—like a patch of grass growing freely in a nook sheltered from the wind—and he wore a rope for a belt.

Zahel was everything Kaladin’s instincts told him to avoid. One learned to evaluate soldiers by the way they kept their uniforms. A neatly pressed coat would not win you a battle—but the man who took care to polish his buttons was often also the man who could hold a formation with precision. Soldiers with scraggly beards and ripped clothing tended to be the type who spent their evenings in drink rather than caring for their equipment.

During the years of the Sadeas/Dalinar divide in the warcamps, these distinctions had become so stark they’d practically been banners. In the face of that, the way Zahel kept himself seemed deliberate. The swordmaster was among the best duelists Kaladin had ever seen, and possessed a wisdom distinct from any other ardent’s or scholar’s. The only explanation was that Zahel dressed this way on purpose to give a misleading air. Zahel was a masterpiece painting intentionally hung in a splintered frame.

Kaladin halted a respectful distance away. Zahel didn’t look at him, but the strange ardent always seemed to know when someone was approaching. He had a surreal awareness of his surroundings. Syl took off toward him, and Kaladin carefully watched Zahel’s reaction.

He can see her, Kaladin decided as Zahel carefully hung another scarf. He arranged himself so he could watch Syl from the corner of his eye. Other than Rock and Cord, Kaladin had never met a person who could see invisible spren. Did Zahel have Horneater blood? The ability was rare even among Rock’s kind—though he had said that occasionally a distant Horneater relative was born with it.

“Well?” Zahel finally asked. “Why have you come to bother me today, Stormblessed?”

“I need some advice.”

“Find something strong to drink,” Zahel said. “It can be better than Stormlight. Both will get you killed, but at least alcohol does it slowly.”

Kaladin walked up beside Zahel. The fluttering scarves reminded him of a spren in flight. Syl, perhaps recognizing the same, turned to a similar shape.

“I’m being forced into retirement,” Kaladin said softly.

“Congratulations,” Zahel said. “Take the pension. Let all this become someone else’s problem.”

“I’ve been told I can choose my place moving forward, so long as I’m not on the front lines. I thought…” He looked to Zahel, who smiled, wrinkles forming at the sides of his eyes. Odd, how the man’s skin could seem smooth as a child’s one moment, then furrow like a grandfather’s the next.

“You think you belong among us?” Zahel said. “The worn-out soldiers of the world? The men with souls so thin, they shiver in a stiff breeze?”

“That’s what I’ve become,” Kaladin said. “I know why most of them left the battlefield, Zahel. But not you. Why did you join the ardents?”

“Because I learned that conflict would find men no matter how hard I tried,” he said. “I no longer wanted a part in trying to stop them.”

“But you couldn’t give up the sword,” Kaladin said.

“Oh, I gave it up. I let go. Best mistake I ever made.” He eyed Kaladin, sizing him up. “You didn’t answer my question. You think you belong among the swordmasters?”

“Dalinar offered to let me train new Radiants,” Kaladin said. “I don’t think I could stand that—seeing them fly off to battle without me. But I thought maybe I could train regular soldiers again. That might not hurt as much.”

“And you think you belong with us?”

“I… Yes.”

“Prove it,” Zahel said, snapping a few scarves off the line. “Land a strike on me.”

“What? Here? Now?”

Zahel carefully wound one of the scarves around his arm. He had no weapons that Kaladin could see, though that ragged tan robe might conceal a knife or two.

“Hand-to-hand?” Kaladin asked.

“No, use the sword,” Zahel said. “You want to join the swordmasters? Show me how you use one.”

“I didn’t say…” Kaladin glanced toward the clothing line, where Syl sat in the shape of a young woman. She shrugged, so Kaladin summoned her as a Blade—long and thin, elegant. Not like the oversized slab of a sword Dalinar had once wielded.

“Dull the edge, chull-brain,” Zahel said. “My soul might be worn thin, but I’d prefer it remain in one piece. No powers on your part either. I want to see you fight, not fly.”

Kaladin dulled Syl’s Blade with a mental command. The edge fuzzed to mist, then reformed unsharpened.

“Um,” Kaladin said. “How do we start the—”

Zahel whipped a sheet off the line and tossed it toward Kaladin. It billowed, fanning outward, and Kaladin stepped forward, using his sword to knock the cloth from the air. Zahel had vanished among the undulating rows of sheets.

Carefully, Kaladin entered the rows. The cloths billowed outward in the wind, but then fluttered down, reminiscent of the plants he’d often passed in the chasms. Living things that moved and flowed with the unseen tides of the blowing wind.

Zahel emerged from another row, pulling a sheet off and whipping it out. Kaladin grunted, stepping away as he swiped at the cloth. That was the man’s strategy, Kaladin realized. Keep Kaladin focused on the cloth.

Kaladin ignored the sheet and lunged toward Zahel. He was proud of that strike; Adolin’s instruction with the sword seemed almost as natural to him now as his old spear training. The lunge missed, but the form was excellent.

Zahel, moving with remarkable spryness, dodged back among the rows of sheets. Kaladin leaped after him, but again managed to lose his quarry. Kaladin turned about, searching the seemingly endless rows of fluttering white sheets. Like dancing flames, pure white.

“Why do you fight, Kaladin Stormblessed?” Zahel’s phantom voice called from somewhere nearby.

Kaladin spun, sword out. “I fight for Alethkar.”

“Ha! You ask me to sponsor you as a swordmaster, then immediately lie to me?”

“I didn’t ask…” Kaladin took a deep breath. “I wear Dalinar’s colors proudly.”

“You fight for him, not because of him,” Zahel called. “Why do you fight?”

Kaladin crept in the direction he thought the sound came from. “I fight to protect my men.”

“Closer,” Zahel said. “But your men are now as safe as they could ever be. They can care for themselves. So why do you keep fighting?”

“Maybe I don’t think they’re safe,” Kaladin said. “Maybe I…”

“… don’t think they can care for themselves?” Zahel asked. “You and old Dalinar. Hens from the same nest.”

A face and figure formed in a nearby sheet, puffing toward Kaladin as if someone were walking through on the other side. He struck immediately, driving his sword through the sheet. It ripped—the point was still sharp enough for that—but didn’t strike anyone beyond.

Syl momentarily became sharp—changing before he could ask—as he swiped to cut the sheet in two. It writhed in the wind, severed down the center.

Zahel came in from Kaladin’s other side, and Kaladin barely turned in time, swinging his Blade. Zahel deflected the strike with his arm, which he’d wrapped with cloth. In his other hand he carried a long scarf that he whipped forward, catching Kaladin’s off hand and wrapping it with shocking tightness, like a coiling whip.

Zahel pulled, yanking Kaladin off balance. Kaladin maintained his feet, barely, and lunged with a one-handed strike. Zahel again deflected the strike with his cloth-wrapped arm. That sort of tactic would never have worked against a real Shardblade, but it could be surprisingly effective against ordinary swords. New recruits were often surprised at how well a nice thick cloth could stop a blade.

Zahel still had Kaladin’s off hand wrapped in the scarf, which he heaved, spinning Kaladin around. Damnation. Kaladin managed to maneuver his Blade and slice the cloth in half—Syl becoming sharp for a moment—then he leaped backward and tried to regain his footing.

Zahel strode calmly to the side, whipping his scarf with a solid crack, then spinning it around like a mace. Kaladin didn’t see any Stormlight coming off the ardent, and he had no reason to believe the man could Surgebind… but the way the cloth had gripped Kaladin’s arm had been uncanny.

Zahel stretched the scarf in his hands—it was longer than Kaladin had expected. “Do you believe in the Almighty, boy?”

“Why does that matter?”

“You ask why faith is relevant when you’re considering joining the ardents—to become a religious advisor?”

“I want to be a teacher of the sword and spear,” Kaladin said. “What does that have to do with the Almighty?”

“All right, then. You ask why God is relevant when you’re considering teaching men to kill?”

Kaladin inched carefully forward, his Blade held before him. “I don’t know what I believe. Navani still follows the Almighty. She burns glyphwards every morning. Dalinar says that the Almighty is dead, but he also claims there’s another true God somewhere in a place beyond Shadesmar. Jasnah says that a being having vast powers doesn’t make them God, and concludes—from the way the world works—that an omnipotent, loving deity cannot exist.”

“I didn’t ask what they believe. I asked what you believe.”

“I’m not confident anyone knows the answers. I figure I’ll let the people who care argue about it, and I’ll keep my head down and focus on my life right now.”

Zahel nodded to him, as if that answer was acceptable. He waved Kaladin forward. Trying to keep his sword form in mind—he’d trained mostly on Smokestance—Kaladin tested forward. He feinted twice, then lunged.

Zahel’s hands became a blur as he pushed the sword to the side with his stretched-out scarf, then twisted his hands around, neatly wrapping the scarf around the sword. That gave him leverage to push the sword farther away as he stepped into Kaladin’s lunge and slid his makeshift wrapping along the length of the Blade, coming in close.

Here, he somehow twisted his cloths around to wrap Kaladin’s wrists as well. Kaladin tried a head-butt, but Zahel stepped into the move and raised one side of the scarf—letting Kaladin’s head go underneath it. With a twirl and a twist, Zahel completely tied Kaladin in the scarf. How long was that thing?

The exchange left Kaladin with not only his hands tied tightly, but a scarf now holding his arms pinned to his sides, Zahel standing behind him. Kaladin couldn’t see what Zahel did next, but it involved sending a loop of scarf up over Kaladin’s head and around Kaladin’s neck. Zahel pulled tight, choking off Kaladin’s air.

I think we’re losing, Syl said. To a guy wielding something he found in Adolin’s sock drawer.

Kaladin grunted, but a part of him was excited. Frustrating as Zahel could be, he was an excellent fighter—and he tested Kaladin in ways he’d never seen before. That was the sort of training he needed in order to beat the Fused.

As Zahel tried to choke him, Kaladin forced himself to remain calm. He changed Syl into a small dagger. A twist of the wrist cut the scarf, which unraveled the entire trap, leaving Kaladin free to spin and slash with his again-dulled knife.

The ardent blocked the knife with his cloth-wrapped arm. He immediately caught Kaladin’s wrist with his other hand, so Kaladin dismissed Syl and summoned her again with his off hand—swinging to make Zahel dodge back.

Zahel snatched a sheet off the fluttering lines, twisting it and wrapping it into a tight length, like a cord.

Kaladin rubbed his neck. “I think… I think I have seen this style before. You fight like Azure does.”

“She fights like me, boy.”

“She’s hunting for you, I think.”

“So Adolin has said. The fool woman will have to get through Cultivation’s Perpendicularity first, so I won’t hold my Breaths waiting for her to arrive.” He waved for Kaladin to come at him again.

Kaladin slipped a throwing knife from his belt, then fell into a sword-and-knife stance. He waved for Zahel to come at him instead. The swordmaster smiled, then threw his sheet at Kaladin. It puffed out, spreading wide as if going for an embrace. By the time Kaladin had cut it down, Zahel was gone, ducking out into the rippling cloth forest.

Kaladin dismissed Syl, then waved toward the ground. She nodded and dived to look under the sheets, searching for Zahel. She pointed in a direction for Kaladin, then dodged between two sheets as a ribbon of light.

Kaladin followed carefully. He thought he caught a glimpse of Zahel through the sheets, a shadow across the cloth.

“Do you believe?” Kaladin asked as he advanced. “In God, or the Almighty or whatever?”

“I don’t have to believe,” the voice drifted back. “I know gods exist. I simply hate them.”

Kaladin dodged between a pair of sheets. In that moment, sheets began ripping free of the lines. They sprang for Kaladin, six at once, and he swore he could see the outlines of faces and figures in them. He summoned Syl and—keeping his head—ignored the unnerving sight and found Zahel.

Kaladin lunged. Zahel—moving with almost supernatural poise—raised two fingers and pressed them to the moving Blade, turning the point aside exactly enough that it missed.

The wind swirled around Kaladin as he stepped into the rippling sheets. They flowed against him—insubstantial—but then entangled his legs. He tripped with a curse, falling to the hard stone.

A second later Zahel had Kaladin’s own knife in hand, pressed to his forehead. Kaladin felt the point right among his scars.

“You cheated,” Kaladin said. “You’re doing something with those sheets and that cloth.”

“I couldn’t cheat,” Zahel said. “This wasn’t about winning or losing, boy. It was for me to see how you fought. I can tell more about a man when the odds are against him.”

Zahel stood and dropped the knife with a clang. Kaladin recovered it, sitting up, and glanced at the fallen sheets. They lay on the ground—normal cloths, occasionally shifting in the breeze. In fact, another man might have dismissed their motions as a trick of the wind.

But Kaladin knew the wind. That had not been the wind.

“You can’t join the ardents,” Zahel said to him, kneeling and touching one of the cloths with his finger, then lifting it and pinning it onto the drying line. He did the same for the others, each in turn.

“Why can’t I?” Kaladin asked. He wasn’t certain Zahel had the authority to forbid him, but he also wasn’t certain he wanted to take this path if Zahel—the one ardent he felt true respect for—was opposed. “Do you make everyone who wants to retire to the ardentia fight you for the privilege?”

“It wasn’t a fight about winning or losing,” Zahel said. “You’re not unwelcome because you lost; you’re unwelcome because you don’t belong with us.” He whipped a sheet in the air, then pinned it in place. “You love the fight, Kaladin. Not with the Thrill that Dalinar once felt, or even with the anticipation of a dandy going to a duel.

“You love it because it’s part of you. It’s your mistress, your passion, your lifeblood. You’d find the daily training unsatisfying. You’d thirst for something more. You’d eventually turn and leave, and that would put you in a worse position than if you’d never started.”

He tossed his scarf at Kaladin’s feet. Though it must have been a different scarf, for the one he’d started with had been bright red, and this one was dull grey.

“Return when you hate the fight,” Zahel said. “Truly hate it.” He walked off between the sheets.

Kaladin picked up the fallen scarf, then glanced at Syl, who descended through the air near him on an invisible set of steps. She shrugged.

Kaladin gripped the cloth, then strode around the sheets. The swordmaster had moved to sit at the rim of the plateau, legs over the edge, staring out across the nearby mountain range. Kaladin dropped the scarf on a pile of others—each of which was now grey.

“What are you?” Kaladin asked. “Are you like Wit?” There had always been something about Zahel, something too knowing. Something distinct, set apart, different from the others.

“No,” Zahel said. “I don’t think there’s anyone else quite like Hoid. I knew him by the name Dust when I was younger. I think he must have a thousand different names among a thousand different peoples.”

“And you?” Kaladin settled down on the stone beside Zahel. “How many names do you have?”

“A few,” Zahel said. “More than I normally share.” He leaned forward, elbows on thighs. Wind blew at the hem of his robe, dangling over a drop of thousands of feet. “You want to know what I am? Well, I’m a lot of things. Tired, mostly. But I’m also a Type Two Invested entity. Used to call myself a Type One, but I had to throw the whole scale out, once I learned more. That’s the trouble with science. It’s never done. Always upending itself. Ruining perfect systems for the little inconvenience of them being wrong.”

“I…” Kaladin swallowed. “I don’t know what any of that meant, but thanks for replying. Wit never gives me answers. At least not straight ones.”

“That’s because Wit is an asshole,” Zahel said. He fished in his robe’s pocket and pulled something out—a small stone in the shape of a curling shell. “Ever seen one of these?”

“Soulcast?” Kaladin asked, taking the small shell. It was surprisingly heavy. He turned it around, admiring the way it curled.

“Similar. That’s a creature that died long, long ago. It settled into the mud, and slowly—over thousands upon thousands of years—minerals infused its body, replacing it axon by axon with stone. Eventually the entire thing was transformed.”

“So… natural Soulcasting. Over time.”

“A long time. A mind-numbingly long time. The place I come from, it didn’t have any of these. It’s too new. Your world might have some hidden deep, but I doubt it. That stone you hold is old. Older than Wit, or your Heralds, or the gods themselves.”

Kaladin held it up, then—out of habit—used a few drops of water from his canteen to reveal its hidden colors and shades.

“My soul,” Zahel said, “is like that fossil. Every part of my soul has been replaced with something new, though it happened in a flash for me. The soul I have now resembles the one I was born with, but it’s something else entirely.”

“I don’t understand.”

“I’m not surprised.” Zahel thought for a moment. “Imagine it this way. You know how you can make an imprint in crem, then let it dry, and fill the imprint with wax to create a copy of your original object? Well, that happened to my soul. When I died, I was drenched in power. So when my soul escaped, it left a duplicate. A kind of… fossil of a soul.”

Kaladin hesitated. “You… died?”

Zahel nodded. “Happened to your friend too. Up in the prison? The one with… that sword.”

“Szeth. Not my friend.”

“The Heralds too,” Zahel said. “When they died, they left an imprint behind. Power that remembered being them. You see, the power wants to be alive.” He gestured with his chin toward Syl, flying down beneath them as a ribbon of light. “She’s what I now call a Type One Invested entity. I decided that had to be the proper way to refer to them. Power that came alive on its own.”

“You can see her!” Kaladin said.

“See? No. Sense?” Zahel shrugged. “Cut off a bit of divinity and leave it alone. Eventually it comes alive. And if you let a man die with too Invested a soul—or Invest him right as he’s dying—he’ll leave behind a shadow you can nail back onto a body. His own, if you’re feeling charitable. Once done, you have this.” Zahel waved to himself. “Type Two Invested entity. Dead man walking.”

What a… strange conversation. Kaladin frowned, trying to figure out why Zahel was telling him this. I suppose I did ask. So… Wait. Maybe there was another reason

“The Fused?” Kaladin asked. “That’s what they are?”

“Yeah,” he said. “Most of us stop aging when it happens, gaining a kind of immortality.”

“Is there a…way to kill something like you? Permanently?”

“Lots of ways. For the weaker ones, just kill the body again, make sure no one Invests the soul with more strength, and they’ll slip away in a few minutes. For stronger ones… well, you might be able to starve them. A lot of Type Twos feed on power. Keeps them going.

“These enemies of yours though, I think they’re too strong for that. They’ve lasted thousands of years already, and seem Connected to Odium to feed directly on his power. You’ll have to find a way to disrupt their souls. You can’t just rip them apart; you need a weapon so strong, it unravels the soul.” He squinted, looking off into the distance. “I know through sorry experience those kinds of weapons are very dangerous to make, and never seem to work right.”

“There’s another way,” Kaladin said. “We could convince the Fused to stop fighting. Instead of killing them, we could find a way to live with them.”

“Grand ideals,” Zahel said. “Optimism. Yeah, you’d make a terrible swordmaster. Be wary of those Fused, kid. The longer one of us exists, the more like a spren we become. Consumed by a singular purpose, our minds bound and chained by our Intent. We’re spren masquerading as men. That’s why she takes our memories. She knows we aren’t the actual people who died, but something else given a corpse to inhabit…”

“She?” Kaladin asked.

Zahel didn’t respond, though when Kaladin handed back the stone shell, Zahel took it. As Kaladin hiked off, the swordmaster cradled it to his chest, staring out toward the endless horizon.

Excerpted from Rhythm of War, copyright ©2020 Dragonsteel Entertainment.

Join the Rhythm of War Read-Along Discussion for this week’s chapters!

Rhythm of War, Book 4 of The Stormlight Archive, is available for pre-order now from your preferred retailer.

(U.K. readers, click here.)

Buy the Book

Rhythm of War