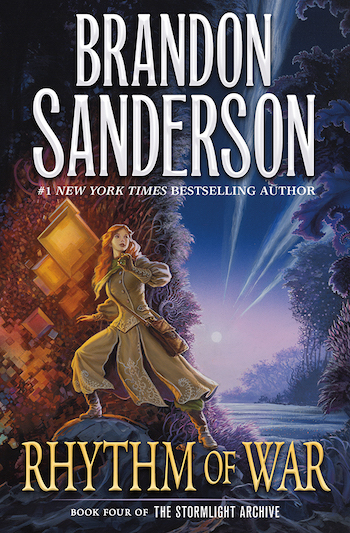

On November 17, 2020, The Stormlight Archive saga continues in Rhythm of War, the eagerly awaited fourth volume in Brandon Sanderson’s #1 New York Times bestselling fantasy series.

Tor.com is serializing the new book from now until release date! A new installment will go live every Tuesday at 9 AM ET.

Every chapter is collected here in the Rhythm of War index. Listen to the audiobook version of this chapter below the text, or go here for the full playlist.

Once you’re done reading, join our resident Cosmere experts for commentary on what this week’s chapter has revealed!

Want to catch up on The Stormlight Archive? Check out our Explaining The Stormlight Archive series!

Chapter 9

Contradictions

A pewter cage will cause the spren of your fabrial to express its attribute in force—a flamespren, for example, will create heat. We call these augmenters. They tend to use Stormlight more quickly than other fabrials.

—Lecture on fabrial mechanics presented by Navani Kholin to the coalition of monarchs, Urithiru, Jesevan, 1175

By the time Kaladin started to come to himself, the Fourth Bridge had already begun lifting into the air. He stood near the railing, watching Hearthstone—now abandoned—shrinking beneath them. From this distance, the houses resembled a group of discarded crab shells, shed as the creature grew. Their function served, they were now scattered refuse.

Once, he’d imagined returning to this place triumphant. Instead, that return had eventually brought the town’s end. It surprised him how little it hurt, knowing he’d probably visited his birthplace for the last time.

Well, it hadn’t been home to him in years. Instinctively, he searched out the soldiers of Bridge Four. They were mingled among the other Windrunners and squires on the upper deck, crowding around, talking about something Kaladin couldn’t make out.

The group was so big now. Hundreds of Windrunners—far too many to function as the tight-knit group he’d formed in Sadeas’s army. A groan escaped his lips, and he blamed it on his fatigue.

He settled down on the deck and put his back to the railing. One of the ardents brought him a cup of something warm, which he took gratefully—until he realized the drinks were distributed to the townspeople and refugees, not the other soldiers. Did he look so bad?

Yes, he thought, glancing down at his bloodied and burned uniform. He vaguely remembered stumbling up to the ship with Renarin’s help, then barking at the flood of Windrunners who came to fawn over him. They kept offering him Stormlight, but he had plenty. It surged in his veins now, but for once the extra energy it lent seemed… wan. Faded.

Stop, he thought forcibly. You’ve held yourself together in rougher winds than this, Kaladin. Breathe deeply. It will pass. It always does.

He sipped his drink, which turned out to be broth. He welcomed its warmth, especially as the ship gained elevation. Many of the townspeople gathered near the sides, awespren bursting around them. Kaladin forced out a smile as he closed his eyes and leaned his head back, trying to recapture the wondrous feeling of taking to the air those first few times.

Instead, he found himself reliving other darker times. When Tien had died, and when he’d failed Elhokar. Foolish though it was, the second one hurt almost as much as the first. He hadn’t particularly liked the king. Yet somehow, seeing Elhokar die as he nearly spoke the first Radiant Ideal…

Kaladin opened his eyes as Syl flew up in the form of a miniature Fourth Bridge. She often took the shape of natural things, but this one seemed extra odd. It didn’t belong in the sky. One might argue that Kaladin didn’t either.

She re-formed into the shape of a young woman, wearing her more stately dress, and landed at eye level. She waved toward the gathered Windrunners. “They’re congratulating Laran,” Syl explained. “She spoke the Third Ideal while we were in that burning building.”

Kaladin grunted. “Good for her.”

“Are you going to congratulate her?”

“Later,” Kaladin said. “Don’t want to force my way through the crowd.” He sighed, pressing his head back against the railing again.

Why didn’t I kill him? he thought. I’ll kill parshmen and Fused for existing, but when I face Moash, I lock up? Why?

He felt so stupid. How had he been so easy to manipulate? Why hadn’t he simply rammed his spear into Moash’s too-confident face and saved the world a whole ton of hassle? At the least it would have shut the man up. Stopped the words that dripped from his mouth like sludge…

They’re going to die… Everyone you love, everyone you think you can protect. They’re all going to die anyway. There’s nothing you can do about it.

I can take away the pain…

Kaladin forced his eyes open and found Syl standing before him wearing her more usual dress—the flowing, girlish one that faded to mist around her knees. She seemed smaller than normal.

“I don’t know what to do,” she said softly. “To help you.”

He glanced down.

“The darkness in you is better some times, worse others,” she said. “But lately… it’s grown into something different. You seem so tired.”

“I just need some good rest,” Kaladin said. “You think I’m bad now? You should’ve seen me after Hav made me hike at double time across… across…”

He turned away. Lying to himself was one thing. Lying to Syl was harder.

“Moash did something to me,” he said. “Put me into some kind of trance.”

“I don’t think he did, Kaladin,” she whispered. “How did he know about the Honor Chasm? And what you nearly did there?”

“I told him a lot of things, back during better days. In Dalinar’s army, before Urithiru. Before…”

Why couldn’t he remember those times, the warm times? Sitting at the fire with real friends?

Real friends including a man who had just tried to persuade him to go kill himself.

“Kaladin,” Syl said, “it’s getting worse. This… distance to your expression, this fatigue. It happens whenever you run out of Stormlight. As if… you can only keep going while it’s in you.”

He squeezed his eyes shut.

“You freeze whenever you hear reports of lost Windrunners.”

When he heard of his soldiers dying, he always imagined running bridges again. He heard the screams, felt the arrows in the air…

“Please,” she whispered. “Tell me what to do. I can’t understand this about you. I’ve tried so hard. I can’t seem to make sense of how you feel or why you feel that way.”

“If you ever do figure it out,” he said, “explain it to me, will you?”

Why couldn’t he simply shrug off what Moash had said? Why couldn’t he stand up tall? Stride toward the sun like the hero everyone pretended he was?

He opened his eyes and took a sip of his broth, but it had gone cold. He forced it down anyway. Soldiers couldn’t afford to be picky about nourishment.

Before long, a figure broke from the crowd of Windrunners and ambled toward him. Teft’s uniform fit neatly and his beard was trimmed, but he seemed like an old stone now that he wasn’t glowing anymore. The type of mossy stone you found sitting at the base of a hill, marked by rain and the winds of time; it left you wondering what it had seen in its many days.

Teft started to sit next to Kaladin.

“I don’t want to talk,” Kaladin snapped. “I’m fine. You don’t need to—”

“Oh, shut up, Kal,” Teft said, sighing as he settled down. He was in his early fifties, but sometimes acted like a grandfather some twenty years older. “In a minute here, you’re going to go congratulate that girl for saying her Third Ideal. It was rough on her, like it is on most of us. She needs to see your approval.”

A protest died on Kaladin’s lips. Yes, he was highmarshal now. But the truth was, every officer worth his chips knew there was a time to shut your mouth and do what your sergeant told you. Even if he wasn’t your sergeant anymore; even if there wasn’t a squad anymore.

Teft looked up at the sky. “So, the bastard is still alive, is he?”

“We had a confirmed sighting of him two months ago, at that battle on the Veden border,” Kaladin said.

“Aye, two months ago,” Teft said. “But I figured someone on their side would have killed him by now. Have to assume they can’t stand him either.”

“They gave him an Honorblade,” Kaladin said. “If they can’t stand him, they have an odd way of showing it.”

“What did he say?”

“That you were all going to die,” Kaladin said.

“Ha? Empty threats? He’s gone crazy, that one has.”

“Yeah,” Kaladin said. “Crazy.”

It wasn’t a threat though, Kaladin thought. I am going to lose everyone eventually. That’s how it works. That’s how it always works…

“I’ll tell the others he’s sniffing around,” Teft said. “He might try to attack some of us in the future.” Teft eyed him. “Renarin said he found you kneeling there. No weapon in hand. Like you’d frozen in battle.”

Teft left the sentence dangling, implying a little more. Like you’d frozen in battle. Again. It hadn’t happened that often. Only this time, and that time in Kholinar. And the time when Lopen had nearly died a few months back. And… well, a few others.

“Let’s go talk to Laran,” Kaladin said, standing up.

“Lad…”

“You told me I had to do this, Teft,” Kaladin said. “You can storming let me get to it.”

Teft fell in behind him as Kaladin went and did his duty. He let them see him stand tall, let them be reassured he was still the brilliant leader they all knew. He had Laran summon her new Blade for him, and he congratulated her spren. They had few enough honorspren that he tried to always acknowledge them.

Afterward, as he’d hoped, Dalinar requested Windrunners to fly him, Navani, and a few of the others to the Shattered Plains. Many of the Radiants would stay behind to guard the Fourth Bridge as it made its longer voyage, but the command staff was needed for other duties.

After seeing to his parents—who of course decided to stay with the townspeople—Kaladin took off. At least with the wind rushing around them during flight, Teft couldn’t ask any more questions.

***

Navani both loved and detested contradictions.

On one hand, contradictions in nature or science were testaments to the logical, reasonable order of all things. When a hundred items indicated a pattern, then one broke that pattern, it showcased how remarkable the pattern was in the first place. Deviation highlighted natural variety.

On the other hand, that deviant stood out. Like a fraction on a page of integers. A seven within a sequence of otherwise sublime multiples of two. Contradictions whispered that her knowledge was incomplete.

Or—worse—that maybe there was no sequence. Maybe everything was random chaos, and she pretended the world made sense for her own peace of mind.

Navani flipped through her notes. Her featureless round chamber was too small to stand up in. It had a table—bolted to the floor—and a single chair. She could touch the walls to both sides simultaneously by stretching out her arms.

A goblet to hold spheres was affixed to the table and fastened shut at the top. She’d brought only diamonds for light, naturally. She couldn’t stand when her light was made up of a hundred different colors and sizes of gems.

She stretched her legs forward under the table, sighing. Hours spent in this room made her long to get up and go for a walk. That wasn’t a possibility, so instead she laid out the offending pages on her desk.

Jasnah enjoyed finding inconsistencies in data. Navani’s daughter seemed to thrive on contradictions, little deviations in witness testimony, questions raised by a historical account’s biased recollections. Jasnah picked carefully at such threads, pulling at them to discover new insights and secrets.

Jasnah loved secrets. Navani was more wary of them. Secrets had turned Gavilar into… whatever it was he’d been at the end. Even today, the greed of artifabrians across the world prevented the greater society from learning, growing, and creating—all in the name of preserving trade secrets.

How many secrets had the ancient Radiants preserved for centuries, only to lose them in death—forcing Navani to have to discover everything anew? She reached down beside her chair and picked up the fabrial Kaladin and Lift had discovered.

She had no idea what to make of the thing. A collection of four garnets? No spren appeared to be trapped in any of them. She didn’t recognize the metal of its cage, the cut of its gemstones… Studying the thing was like trying to understand a foreign language. How had it suppressed the Radiants’ abilities? Was this related to the gemstones embedded in the weapons of the enemy soldiers, the ones that drained away Stormlight? So many storming secrets.

She held up a sketch of the gemstone pillar at the heart of Urithiru. It is the same, she thought, turning the fabrial in her hand, then comparing it to a similar-looking construction of garnets in the picture. The ones in the pillar were enormous, but the cut, the arrangement of stones, the feel was the same.

Why would the tower have a device to suppress the powers of Radiants? It was their home.

Could it be the opposite? she thought, putting down the alien fabrial and making a note in the margins of the drawing. A way to suppress the abilities of the Fused?

So much about the tower still didn’t make any sense. She had a Bondsmith in Dalinar. Shouldn’t he and the Stormfather be able to mimic whatever the long-dead tower spren had done to power the pillar and the tower?

She held up a second picture, this one of a more familiar device—a construction of three gemstones connected by chains, meant to be worn on the back of the hand. A Soulcaster.

Soulcasters had long bothered Navani. They were the proverbial flaw in the system, the fabrial that didn’t make sense. Navani wasn’t a scholar herself, but she had a strong working knowledge of fabrials. They produced certain effects, mostly amplifying, locating, or attracting specific elements or emotions—always tied to the type of spren trapped inside. The effects were so logical that theoretical fabrials had been correctly predicted years before their successful construction.

A technological masterpiece like the Fourth Bridge was no more than a collection of smaller, simpler devices intertwined. Pair one set of gemstones, and you had a spanreed. Interwork hundreds, and you could make a ship fly. Assuming you’d discovered how to isolate planes of motion and reapply force vectors through conjoined fabrials. But even these discoveries had been more small tweaks than revolutionary changes.

Each step built on the previous ones in logical ways. It made perfect sense, once you understood the fundamentals. But Soulcasters… they broke all the rules. For centuries, everyone had explained them as holy objects. Created by the Almighty and granted to men in an act of charity. They weren’t supposed to make sense, because they weren’t technological, but divine.

But was that really true? Or could she, with study, eventually discover their secrets? For years, they’d assumed no spren were trapped in Soulcasting devices. But with the Oathgates, Navani could travel into Shadesmar—and everything in the Physical Realm reflected there. Human beings manifested as floating candle flames. Spren manifested as larger, or more complete versions of what was seen in the Physical Realm.

Soulcasters manifested as small unresponsive spren, hovering with their eyes closed. So the Soulcasters did have a captured spren. A Radiant spren, judging by their shape. Intelligent, rather than the more animal-like spren captured to power normal fabrials.

These spren were held captive in Shadesmar, and made to power Soulcasters. Is this the same, perhaps? Navani thought, holding up the gemstone device Kaladin had discovered. There had to be a connection. And perhaps a connection to the tower? The secret to making it function?

Navani shuffled through pages in her notebook, looking at the multitude of schematics she’d drawn during the last year. She’d been able to piece together many of the tower’s mechanics. Though they were—like Soulcasters—created by somehow trapping spren in Shadesmar. Their functions, however, were similar to the ones designed by modern artifabrians.

The moving lifts? A combination of conjoined fabrials and a hidden waterwheel that dipped into an underground river, which flowed from melting snow in the peaks. The city’s wells constantly replenished with fresh water? A clever manipulation of attractor fabrials, powered by ancient gemstones exposed to the air and the storms far beneath the tower.

Indeed, the more she studied Urithiru, the more she saw the ancients using simple fabrial technology to create their marvels. Modern artifabrians had exceeded such constructs; her engineers had repaired, refitted, and streamlined the lifts, making them function at several times their original speed. They’d enhanced the wells and pipes, which could now draw water farther up the tower into long-abandoned waterways.

She’d learned so much in the last year. She’d almost started to feel she could deduce it all—answer the questions pertaining to time and to creation itself.

Then she remembered Soulcasters. Their armies ate and remained mobile because of Soulcasters. Urithiru depended on extra food from Soulcasters. The Soulcaster cache discovered in Aimia earlier in the year had brought an incredible boon to the coalition armies. They were among the most coveted, important devices in modern history.

And she didn’t know how they worked.

Navani sighed, snapping her notebook shut. Her little room trembled as she did so, and she frowned, leaning to the side and opening a small hatch in the wall. She looked out through the glass at an incongruous sight—a group of people flying in the air alongside her. The Windrunners held a loose formation, facing into the wind—which Navani had pointed out was a little ridiculous. Why not fly the other way? You didn’t need to see where you were going.

They’d claimed that flying feet-first felt silly, and had refused, no matter how much sense it made. They did seem to sculpt the air around themselves and prevent their faces from being buffeted by the worst of the winds. Dalinar, however, had no such protection. He flew in the line—kept aloft by a Windrunner—and wore a face mask with goggles to keep his proud nose from freezing right off.

Navani opted for a more comfortable conveyance. Her “room” was a person-size wooden sphere with long tapering points at either end to help with airflow. The simple vehicle was infused by a Windrunner, then Lashed into the sky. This way, Navani could ride in comfort and get some studying done during extended travel.

Dalinar claimed that he liked the feeling of the wind in his face, but Navani suspected that he found her vehicle too close to an airborne version of a palanquin. A woman’s vehicle. One might assume that—in deciding to learn how to read—Dalinar would no longer worry about what was traditionally considered masculine or feminine. But the male ego could be as complicated as the most intricate fabrial.

She smiled at his mask and three layers of coats. Nearby, lithe scouts in blue flitted one way or another. Dalinar looked like a chull that had found itself among a flock of skyeels and was doing its best to pretend to fit in.

She loved that chull. Loved his stubbornness, the concern he took for every decision. The way he thought with intense passion. You never got half of Dalinar Kholin. When he put his mind to something, you got the whole man—and had to simply pray to the Almighty that you could handle him.

She checked her clock. A trip like this, all the way from Alethkar to the Shattered Plains, still took close to six hours—and that was with a triple Lashing, using Dalinar’s power to provide Stormlight.

Thankfully, they were nearing the end, and she saw the Shattered Plains approaching ahead. Her engineers had been busy; over the last year they’d constructed sturdy permanent bridges connecting many of the relevant plateaus. They desperately needed to be able to farm this region to supply Urithiru—and that meant dealing with Ialai Sadeas and her rebels. Hopefully Navani would soon hear good news from the Lightweavers and their mission to—

Navani cocked her head, noticing something odd. The wall beside her reflected a faint shade of red, blinking on and off. Like the light of a spanreed.

Her immediate thought was panic. Had she somehow activated the strange fabrial? If the powers of the Windrunners vanished, she’d drop from the air like a stone. Her heart leapt, and her breath caught.

She didn’t start plummeting. And… the light wasn’t coming from the strange fabrial. She leaned back, then peeked under her table. There, stuck to the bottom with some wax, was a tiny ruby. No, half a ruby. Part of a spanreed, she thought, picking it free with her fingernail.

She held it up between her fingers and studied the steady pulsing light. Yes, this was a spanreed ruby—when inserted into a spanreed, it would connect her to someone with the other half, allowing them to communicate. It had clearly been stuck here for her to find. But who would do it so sneakily?

The Windrunners began lowering her vehicle down near the center of the Shattered Plains, and she found herself increasingly excited by the blinking light. A spanreed wouldn’t work if she was in a moving vehicle, but as they landed, she dug one of her own reeds from her supplies. She had the new ruby affixed and a piece of paper in place before anyone had time to check on her.

She turned the ruby, eager to see what the unknown figure wanted to say to her.

You must stop what you are doing, the pen wrote out, using a cramped, nearly illegible version of the Alethi women’s script. Immediately. It waited for a response.

What a strange message. Navani turned the ruby and wrote her response, which would be copied for whoever had the other side of the ruby. I’m not sure what you mean, she wrote. Who are you? I don’t believe I’m doing anything that needs to be halted. Perhaps you don’t know the identity of the person you are writing to. Has this spanreed been misplaced?

Navani set the spanreed into position for a response, then turned the ruby. When she removed her hand, the pen remained in position on the paper, upright. Then it started moving on its own, worked by the unseen person on the other end.

I know who you are, it wrote. You are the monster Navani Kholin. You have caused more pain than any living person.

She cocked her head. What on Roshar?

I couldn’t watch any longer, the pen continued. I had to stop you.

Was it a madwoman who wrote with the other reed? The ruby started blinking, indicating they wanted a response.

All right, Navani wrote. Why don’t you tell me what it is you want me to stop? Also, you have neglected to give me your name.

The response came quickly, written as if by a fervent hand.

You capture spren. You imprison them. Hundreds of them. You must stop. Stop, or there will be consequences.

Spren? Fabrials? This woman couldn’t seriously be concerned about such a simple thing, could she? What was next? Complaining about chulls that pull carts?

I have spoken with intelligent spren, Navani wrote, such as those bonded to the Radiants. They agree that the spren we use for our fabrials are not people, but are as unthinking as animals. They may not like the idea of what we do, but they don’t think it monstrous. Even the honorspren accept it.

The honorspren cannot be trusted, the pen wrote. Not anymore. You must stop creating this new kind of fabrial. I will make you stop. This is your warning.

The pen halted, and try though she might, Navani couldn’t get any further responses from the mysterious woman or ardent who had written to her.

***

The Windrunners at Urithiru had been called to one of the battlefronts for air support, and Kaladin was still busy with his little enterprise in Alethkar. So in the end, Shallan and her team had to travel to Narak the hard way. Fortunately, the “hard way” wasn’t too bad these days. With permanent bridges and a direct path maintained by soldiers, a journey that had once taken days had been reduced to a few hours.

At the first main fortified plateau where Dalinar kept standing troops to watch the warcamps, Shallan and Adolin were able to deliver up the prisoners—with instructions for them to be brought to Narak for questioning. Adolin and Shallan requisitioned a carriage, and left the rest of the troops to make their way back more slowly.

Shallan passed the time looking out the carriage window, listening to the clopping of the horses and watching the fractured landscape of plateaus and chasms. Once this had all been so difficult to traverse. Now she did it in a plush carriage, and considered that inconvenient compared to being flown about by a Windrunner. How would it be once Navani got her flying devices working efficiently? Would flying by Windrunner be the inconvenience then?

Adolin scooted over beside her, and she felt his warmth. She closed her eyes and melted into him, breathing him in—as if she could feel his soul brushing against her own.

“Hey,” he said. “It’s not so bad. Really. Father knew this plan might come to fighting. If Ialai had been willing to quietly rule in the warcamps, we’d have left her alone. But we couldn’t ignore someone sitting in our backyard raising an army to depose us.”

Shallan nodded.

“That’s not what you’re worried about, is it?” Adolin asked.

“No. Not completely.” She turned and pressed her face into his chest. He’d removed his jacket, and the shirt beneath reminded her of when he came to their rooms after sparring. He always wanted to bathe immediately, and she… well, she rarely let him. Not until she was done with him, at least.

They rode in silence for some time, with Shallan snuggled against him. “You never push,” she eventually said. “Though you know I keep secrets from you.”

“You’ll tell me eventually.”

She gripped his shirt tight between her fingers. “It bothers you though, doesn’t it?”

He didn’t reply at first, which was different from his normal cheery assurances. “Yeah,” he finally said. “How could it not? I trust you, Shallan. But sometimes… I wonder if I can trust all three of you. Veil especially.”

“She’s trying to protect me in her own way,” Shallan said.

“And if she does something you or I wouldn’t want her to? Gets… physical with someone?”

“That’s not a worry,” Shallan said. “I promise, and she will too if you ask her. We have an understanding. I’m not worried about you and me, Adolin.”

“What are you worried about, then?”

She pulled closer, and couldn’t help imagining it. What he would do if he knew the real her. If he knew all the things she’d actually done.

It wasn’t just about him. What if Pattern knew? Dalinar? Her agents?

They would leave, and her life would become a wasteland. She’d be alone, as she deserved. Because of the truths she hid, her entire life was a lie. Shallan, the one they all knew best, was the fakest mask of them all.

No, Radiant said. You can face it. You can fight it. You imagine only the worst possible outcome.

But it’s possible, isn’t it? Shallan asked. It’s possible that they would leave me if they knew.

Radiant had no reply. And deep within Shallan, something else stirred. Formless. She had told herself that she would never create a new persona, and she wouldn’t. Formless wasn’t real.

But the possibility of it frightened Veil. And anything that frightened Veil terrified Shallan.

“I will explain someday,” Shallan said softly to Adolin. “I promise. When I’m ready.”

He squeezed her arm in reply. She didn’t deserve him—his goodness, his love. That was the trap she’d found herself in. The more he trusted her, the worse she felt. And she didn’t know how to get out. She couldn’t get out.

Please, she whispered. Save me.

Veil reluctantly emerged. She sat up, not pulling against Adolin any longer—and he seemed to understand, shifting his position in the seat. He had an uncanny ability to tell which of her was in control.

“We’re trying to help,” Veil said to him. “And we think that this year has been good for Shallan, overall. But right now, it’s probably better if we discuss another topic.”

“Sure,” Adolin said. “Can we talk about the fact that Ialai was more frightened of capture than death?”

“She… didn’t kill herself, Adolin,” Veil said. “We are reasonably certain she died from a pinprick of poison.”

He sat up straight. “So you’re saying someone in our team did it? One of my soldiers or one of your agents?” He paused. “Or… did you do it, Veil?”

“I didn’t,” Veil said. “But would it have been so bad if I had? We both know she needed to die.”

“She was a defenseless woman!”

“And it’s that different from what you did to Sadeas?”

“He was a soldier,” Adolin said. “That’s what makes it different.” He glanced out the window. “Maybe. Father thinks I did something terrible. But… I was right, Veil. I’m not going to let someone hide behind social propriety while threatening my family. I won’t let them use my honor against me. And… Stonefalls. I say things like that, and…”

“And it doesn’t sound so different from killing Ialai,” Veil said. “Regardless, I didn’t kill her.”

Shallan, having had a short breather, started to reemerge. Veil retreated, letting Shallan lean up against Adolin. He, though tense at first, let her do so.

She rested her head on his chest, listening to his heartbeat. His life. Pulsing within him like the thunder of a captive storm. Pattern seemed to sense the way that pulse calmed her, for he began humming from where he hung on the roof.

She would tell Adolin everything, eventually. She’d told him some already. About her father, and her mother, and her life in Jah Keved. But not the deepest things, the things she didn’t even remember herself. How could she tell him things that were clouded in her own memory?

She also hadn’t told him about the Ghostbloods. She wasn’t certain she could share that secret, but could… could she try? Begin, at least? At Veil and Radiant’s prompting, she searched for a way. After all, Dalinar kept saying that the next step was the most important one.

“There’s something you need to know,” she said. “Before you came in, Ialai implied that if I took her captive, she would be killed. She knew the blow was coming—that’s why I was suspicious of her death. She also said she didn’t kill Thanadal. That it was another group called the Ghostbloods. She thought the Ghostbloods would send someone for her—which was why she was certain she’d die.”

“We’ve been hunting them. Ialai was leading them.”

“No, dear, she was leading the Sons of Honor. The Ghostbloods are a different group.”

He scratched his head. “Are they the ones your… brother Helaran belonged to? The one that attacked Amaram, right? And Kaladin killed Helaran without knowing who he was?”

“Those were the Skybreakers. They’re not so secret any longer. They joined with the enemy—”

“Right. Radiants on the other team.” Those likely made sense to him, as he’d taken battlefield reports on them. The shadowy groups moving at night, on the other hand, were something he couldn’t fight directly. Dealing with them was to be her job.

She dug in her pocket as the carriage rolled over a particularly robust series of bumps. This path hadn’t been graded or leveled, and though the carriage driver did his best to miss the larger rockbuds, there was only so much he could do.

“The Ghostbloods,” Shallan said, “are the people who tried to kill Jasnah—and me by extension—by sinking our ship.”

“So they’re on Odium’s side,” Adolin said.

“It’s more complicated than that. Honestly, I’m not sure what they want, besides secrets. They were trying to get to Urithiru before Jasnah, but we beat them to it.” Led them to it might have been more accurate. “I’m not at all sure what they want those secrets for.”

“Power,” Adolin said.

That response—the same one she’d given to Ialai—now seemed so simplistic. Mraize, and his inscrutable master Iyatil, were deliberate, precise people. Perhaps they were merely seeking to glean leverage or wealth from chaos of the end of the world. Shallan realized she would be disappointed to discover that their plans were so pedestrian. Any corpse robber on a battlefield could exploit the misfortune of others.

Mraize was a hunter. He didn’t wait for opportunities. He went out and made them.

“What’s that?” Adolin asked, nodding to the book in her hand.

“Before she died,” Shallan said. “Ialai gave me a hint that led me to search the room and find this.”

“That’s why you didn’t want the guards to do it,” he said. “Because one of them might be a spy or assassin. Storms.”

“You might want to reassign your soldiers to boring, out-of-the-way posts for a season.”

“These are some of my best men!” Adolin complained. “Highly decorated! They just pulled off an extremely dangerous covert operation.”

“So give them a rest at some quiet post,” Shallan said. “Until we figure this out. I’ll watch my agents. If I discover it’s one of them, you can bring the men back.”

He sulked at the suggestion; he hated the idea of punishing a group of good men because one of them might be a spy. Adolin might claim he was different from his father, but in fact they were two shades of the same paint. Often, two similar colors clashed worse than wildly different ones would.

Shallan kicked the bag of notes and letters that Gaz had gathered, resting at their feet. “We’ll give that to your father’s scribes, but I’ll look through this book personally.”

“What’s in it?” Adolin asked, leaning to the side so he could see—but there were no pictures.

“I haven’t read the entire thing,” Shallan said. “It seems to be Ialai’s attempts to piece together what the Ghostbloods are planning. Like this page—a list of terms or names her spies had heard. She was trying to define what they were.” Shallan moved her finger down the page. “Nalathis. Scadarial. Tal Dain. Do you recognize any of those?”

“They sound like nonsense to me. Nalathis might have something to do with Nalan, the Skybreaker Herald.”

Ialai had noticed the same connection, but indicated these names might be places—ones she could not find in any atlas. Perhaps they were like Feverstone Keep, the place Dalinar had seen in his visions. Somewhere that had disappeared so long ago, no one remembered the name anymore.

Circled several times on one page at the end of the list was the word “Thaidakar” with the note, He leads them. But who is he? The name seems a title, much like Mraize. But neither are in a language I know.

Shallan was pretty sure she’d heard Mraize use the name Thaidakar before.

“So, this is our new mission?” Adolin asked. “We find out what these Ghostblood people are up to, and we stop them.” He took the palm-size notebook from her and flipped through the pages. “Maybe we should give this to Jasnah.”

“We will,” she said. “Eventually.”

“All right.” He gave it back, then put his arm around her and pulled her close. “But promise me that you—and I mean all of you—will avoid doing anything crazy until you talk to me.”

“Dear,” she said, “considering who you’re talking to, anything I am prone to try will be—by definition—crazy.”

He smiled at that, but gave her another comforting hug. She settled into the nook between his arm and chest, though he was too muscly to make a good pillow. She continued reading, but it wasn’t until an hour or so later that she realized—despite dancing around the topic with him—she hadn’t revealed she was a member of the Ghostbloods.

They were likely to put Shallan in the middle of whatever they were up to. So far—despite telling herself she was spying on them—she’d basically achieved every goal they’d asked of her. That meant a crisis was coming. The inflection point, past which she could not continue down this duplicitous path. Keeping secrets from Adolin was eating at her from the inside. Fueling Formless, pushing it toward a reality.

She needed a way out. To leave the Ghostbloods, break ties. Otherwise they’d get inside her head. And it was way too crowded in there already.

I didn’t kill Ialai though, Shallan thought. I was close to it, but I didn’t. So I’m not theirs entirely.

Mraize would want to speak to her about the mission, and about some other things she’d been doing for him, so she could bet on him visiting her soon. Maybe when he did, she would finally find the strength to break with the Ghostbloods.

Excerpted from Rhythm of War, copyright ©2020 Dragonsteel Entertainment.

Join the Rhythm of War Read-Along Discussion for this week’s chapters!

Rhythm of War, Book 4 of The Stormlight Archive, is available for pre-order now from your preferred retailer.

(U.K. readers, click here.)

Buy the Book

Rhythm of War