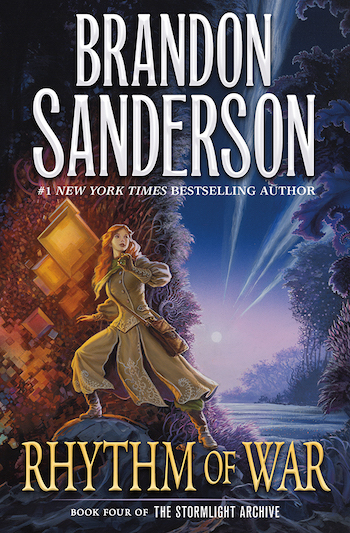

On November 17, 2020, The Stormlight Archive saga continues in Rhythm of War, the eagerly awaited fourth volume in Brandon Sanderson’s #1 New York Times bestselling fantasy series.

Tor.com is serializing the new book from now until release date! A new installment will go live every Tuesday at 9 AM ET.

Every chapter is collected here in the Rhythm of War index. Listen to the audiobook version of this chapter below the text, or go here for the full playlist.

Once you’re done reading, join our resident Cosmere experts for commentary on what this week’s chapter has revealed!

Want to catch up on The Stormlight Archive? Check out our Explaining The Stormlight Archive series!

Chapter 19

Garnets

The world becomes an increasingly dangerous place, and so I come to the crux of my argument. We cannot afford to keep secrets from one another any longer. The Thaylen artifabrians have private techniques relating to how they remove Stormlight from gems and create fabrials around extremely large stones.

I beg the coalition and the good people of Thaylenah to acknowledge our collective need. I have taken the first step by opening my research to all scholars.

I pray you will see the wisdom in doing the same.

—Lecture on fabrial mechanics presented by Navani Kholin to the coalition of monarchs, Urithiru, Jesevan, 1175

“I’m sorry, Brightness,” Rushu said, holding up several schematics as they walked around the crystalline pillar deep within Urithiru. “Weeks of study, and I can’t find any other matches.”

Navani sighed, pausing beside a particular section of the pillar. Four garnets stood out, the same construction used in the suppression fabrial. The layouts were too precise, too exact, to be a coincidence.

It had seemed like a breakthrough, and she’d set Rushu and the others comparing all other known fabrials to the pillar, searching for any that seemed similar. That once-promising lead, unfortunately, had reached another dead end.

“There’s another problem,” Rushu said.

“Only one?” When the young ardent frowned, Navani waved for her to continue. “What is it?”

“We inspected the suppression fabrial in Shadesmar, as you asked,” Rushu said. “Your theory is correct, it manifests a spren in Shadesmar as Soulcasters do. But on this side, there is no sign of that spren in the gemstones.”

“What’s the problem, then?” Navani asked. “My theory is correct.”

“Brightness, the spren that runs the suppression device… has been corrupted, very similar to…”

“To Renarin’s spren,” Navani said.

“Indeed. The spren refused to talk to us, but didn’t seem as insensate as the ones in Soulcasters. This reinforces your theory that ancient fabrials—things like the pumps, the Oathgates, and the Soulcasters—somehow imprisoned their spren in the Cognitive Realm. When we pressed it, the spren closed its eyes pointedly. It seems to be working with the enemy deliberately, which raises questions about your nephew’s spren. Dare we trust it?”

“We have no reason to assume that one spren serving the enemy means all of its type do,” Navani said. “We should assume they each have individual loyalties, like humans.”

She had to admit, however, that Renarin’s spren made her uncomfortable. Seeing the future? Well, she had already tied her mind in knots thinking about Glys. Instead, she tried to focus on the nature of this fabrial’s spren.

You capture spren, the strange person had said to her via spanreed. You imprison them. Hundreds of them. You are a monster. You must stop.

Weeks had passed without a quiver from the spanreed. Was it possible this person knew how to create fabrials the old way, which appeared to use sapient spren, locking them in the Cognitive Realm? Perhaps this method was preferable and more humane. The magnificent spren that controlled the Oathgates didn’t seem to begrudge their attachment to the devices, for example, and were fully capable of interacting.

“For now, study this,” Navani said to Rushu, tapping her knuckles against the majestic gemstone pillar. “See if you can find a way to activate this specific group of garnets. In the past, the tower was protected from the Fused. Old writings agree on this fact. This part of the pillar must be why.”

“Yes…” Rushu said. “A fine theory, and a fine suggestion. If we focus on this one piece of the pillar, which we know is a distinct fabrial, maybe we can activate it.”

“Also try resetting the suppression fabrial we stole. It smothered Kaladin’s abilities, but let the Fused use their powers. There might be a way to reverse the device’s effects.”

Rushu nodded in her absentminded way. Navani continued to stare up at the pillar, which sparkled with the light of a thousand facets. What was she missing? Why couldn’t she activate it?

She handed the schematic to Rushu and began walking from the room. “We haven’t been giving enough thought to the tower’s security,” she said. “Clearly the ancients were worried about incursions by the Fused—and we experienced one already.”

“The Oathgates are under constant guard now,” Rushu said, hurrying to keep up. “And authentication by two different orders of Radiants is required for activation. It seems unlikely the enemy could do what they did before.”

“Yes, but what if they came in another way?” The spren she’d interviewed claimed that the Masked Ones—Fused with Lightweaving powers—couldn’t enter the tower. Its ancient protections had some lingering effects, like the changes in pressure or the warmth. Indeed, this seemed proven, as while Masked Ones sometimes slipped into human camps, they had never come to Urithiru.

At least so far as Navani could tell. Perhaps they’d just been very careful. “The enemy,” Navani said to Rushu, “has abilities we can only guess at—and the powers we do know about are dangerous enough. Masked Ones could be among us and we’d never know it. You or I could be one of them right now.”

“That… is a highly disturbing thought, Brightness,” Rushu said. “What could we possibly do? Other than fixing the tower’s defenses.”

“Gather a team of our best abstract thinkers. Assign them the task of creating protocols to identify hidden Fused.”

“Understood,” Rushu said. “Dali would be perfect for that. Oh, and Sebasinar, and…” She slowed, pulling out her notebook, oblivious to how she was standing in the middle of the corridor, forcing people to step around her.

Navani smiled fondly, but left Rushu to her task, instead turning right and entering one of the ancient “library” rooms. When first studying the tower, they’d found dozens of gemstones in this room, all encoded with short messages from the ancient Knights Radiant.

Over the months, the room had transformed from a dedicated study of those gemstones into a laboratory where Navani had organized her finest engineers. She had been around enough intelligent people to know they worked best in an encouraging environment where study and discovery were rewarded.

Inside this room, concentrationspren moved like ripples in the sky, and a few logicspren—like little stormclouds—hovered in the air. Engineers worked on dozens of projects: some practical designs, others more fanciful.

As soon as she stepped in, an excited young engineer scrambled up. “Brightness!” he said. “It’s working!”

“That’s wonderful,” she said, struggling to remember his name. Young, bald, barely a beard to speak of. What project had he been on?

He grabbed her by the arm and towed her to the side, ignoring propriety. She didn’t mind. It was a mark of pride to her that so many of the engineers forgot she was anything other than the person who funded their projects.

She spotted Falilar at the worktable, and that jogged her memory. The young ardent was his nephew, Tomor, a darkeyed youth who wanted to follow his uncle’s path of scholarship. She’d assigned the two one of her more serious designs, a set of new lifts that worked on the same principle as the flying platform.

“Brightness,” Falilar said, bowing to her. “The design requires a great deal more tweaking. I fear it’s going to require too much manpower to be efficient.”

“But it’s working?” Navani said.

“Yes!” Tomor said, bringing her a device shaped like a jewelry box, around six inches square, with a handle on one side. The handle—like the one you might use to pull open a drawer—held a trigger for the index finger on the inside. A button on the top was the box’s only other feature, except for a set of straps that she took for a wrist brace.

Navani accepted the box and peeked in through the access panel. There were two separate fabrial constructions inside. One she recognized for a simple conjoining ruby, like those used in spanreeds. The other was more experimental, a practical application of the designs she’d given Tomor and Falilar: a device for redirecting force, and for quickly engaging or disengaging alignment with the conjoined fabrial.

It wasn’t exactly the same method that kept the Fourth Bridge flying. It was more a cousin to that technology.

“We decided to make the prototype an individual device,” Falilar said, “as you wanted something portable.”

“Here!” Tomor said. “Let me get the workers ready!” He scrambled over to a couple of soldiers at the side of the room, assigned to run errands for the engineers. Tomor got them into position holding a rope, like they were about to engage in a tug-of-war—only instead of a rival team on the other end, their rope was attached to a different fabrial box on the floor.

“Go ahead, Brightness!” Tomor said. “Point your box to the side, then conjoin the rubies!”

Navani strapped the device to her wrist, then swung her arm around, pointing it to the side. Right now, the rubies weren’t conjoined, allowing the box to move freely. Once she pressed the button, however, the device snapped into conjoinment with the second box, the one on the floor attached to the rope.

Next, she pulled the trigger with her index finger. This made the ruby flash brightly for the soldiers, who began pulling their rope. They moved their box along the floor, and the force was transferred across the space to Navani. And she was yanked—by the box and handle strapped to her wrist—steadily across the room.

It was a common application of conjoined fabrials. The big difference here was not in the fact that force was being transferred, but the direction of the transfer. The men were pulling the box backward along the wall, moving steadily eastward. Navani was being pulled forward along the axis where she’d pointed her arm—a random direction south by southwest.

She flashed the light to warn the soldiers, then disjoined the fabrials, so she stopped skidding. The men were ready for this, and prepared as she pointed her hand in a different direction. When she conjoined again and flashed the ruby for the men, they began pulling—and she moved that way instead.

“It’s working wonderfully,” Navani said, skidding on her heels. “The ability to redirect the force in any direction—on the fly—is going to have huge practical applications.”

“Yes, Brightness,” Falilar said, walking beside her, “I agree—but the manpower issue is a serious one. It already requires the work of hundreds to keep the Fourth Bridge in the air and moving. How many more can we spare?”

Fortunately, that was the exact problem Navani had been trying to solve. This is working, she thought with excitement, turning off the fabrial, then having the men pull her in a third direction. Making the Fourth Bridge rise into the air had not been terribly difficult—the truly hard part had been getting it to move laterally after raising it into the air.

The secret to making the Fourth Bridge fly—and to make this handheld device work—involved a rare metal called aluminum. It was what the Fused used for weapons that could block Shardblades, but the metal didn’t just interfere with Shardblades—it interfered with all kinds of Stormlight mechanics. Interactions with it during the expedition into Aimia earlier in the year had led Navani to order experiments, and Falilar himself had made the breakthrough.

The trick was to use a specific fabrial cage, made from aluminum, around the conjoined rubies. The details were complicated, but with the proper caging, an artifabrian could make a conjoined ruby ignore motion made by the other along specific vectors or planes. So, in application, the Fourth Bridge could use two different dummy ships to move. One to go up and down, the other to go laterally.

The complexities of that excited Navani and her engineers, and had led to the new device she now wore. She could move her arm in any direction she wanted, conjoin the fabrial, then direct force through it in a specific direction.

Momentum and energy were conserved per natural conjoined fabrial mechanics. Her scientists had tested this a hundred different ways, and some applications quickly drained the fabrial—but they’d known about those from ancient experiments. Still, there were thoughts whirring in her head. There were ways they could use this to directly translate Stormlight energy into mechanical energy.

And she’d been thinking of other ways to replace the manpower needs…

“Brightness?” Falilar said. “You seem concerned. I’m sorry if the device has more problems than you expected. It’s an early iteration.”

“Falilar, you worry too much,” Navani said. “The device is amazing.”

“But… the manpower problem…”

Navani smiled. “Come with me.”

***

A short time later, Navani led Falilar into a section of the twentieth floor of the tower. Here she had another team working—though this one was made up of more laborers and fewer engineers. They’d located a strange shaft, one of many odd features of the tower. This one plummeted through the tower past its basements, eventually connecting to a cavern deep beneath.

Though the original purpose of it baffled their surveyors and scientists, Navani had a plan for the shaft. It had involved setting up several steel weights here, each as heavy as three men, suspended on ropes.

She nodded to the workers as they bowed, several holding up sphere lanterns for her and the ardents as they stepped up to the deep hole, which was a good six feet across. Navani peered over the side, and Falilar joined her, gripping the railing with nervous fingers.

“How far down does it go?” he asked.

“Far past the basement,” Navani said, holding up the box he had constructed. “Let’s say that, instead of men pulling a rope, we bolted the other half of this fabrial to one of these weights. Then we could connect the device’s trigger to these pulleys at the top—so that the trigger dropped the weight.”

“You’d get your arm pulled off!” Falilar said. “You’d be yanked hard in whatever direction you’ve pointed the device.”

“Resistance on the pulley line could modulate the initial force,” Navani said. “Maybe we could make it so the strength of the trigger pull determines how fast the line is let out—and how fast you are propelled.”

“A clever application,” Falilar said, wiping his brow as he glanced at the dark shaft. “It doesn’t do anything about the manpower issue though. Someone has to get those weights back up here.”

“Captain?” Navani asked the soldier leading the crew on this floor.

“The windmills have been set up as requested,” the man said—he was missing an arm, the right sleeve of his uniform sewn up. Dalinar was always on the lookout for a way to keep his wounded officers involved in the important work of the war effort. “I’m told they’re rated for storms, though of course no device can be perfectly protected in a highstorm.”

“What’s this?” Falilar asked.

“Windmills inside steel casings,” Navani said, “with gemstones on the blades—each one conjoined with a ruby on the pulley system up above. The storm blows, and these five weights are ratcheted to the top, potential energy stored for later use.”

“Ah…” Falilar said. “Brightness, I see…”

“Every few days,” Navani said, “the storms gift us an enormous outpouring of kinetic strength. Winds that level forests; lightning as bright as the sun.” She patted one of the ropes with the weights. “We simply need to find a way to store that energy. This could power a fleet of ships. Enough pulleys, weights, and windmills… and we could fly an air force around the world, all using the harnessed energy of the highstorms.”

“How…” Falilar said, his eyes alight. “How do we make this happen, Brightness? What can I do?”

“Testing,” she said, “and iterations. We need systems that can withstand the strain of repeated use. We need more flexibility, more streamlining. Your device here. Can you install a switching mechanism so we can move between fabrials on these five weights? A lift that could go up five times before needing to be recharged is far more useful than one that can go up only once.”

“Yes…” he said. “And we could use the weight of people traveling back down to help recharge some of the weights… Do you want us to make true lifts, or continue with the personal lift device, as Tomor designed? He’s excited by the idea…”

“Do both,” Navani suggested. “Let him continue on the single-person device, but suggest he shape it like a crossbow you point somewhere, rather than a box with a handle. Make it look interesting, and people will be more interested. One of the tricks of fabrial science.”

“Yes… I see, Brightness.”

She checked the clock she wore in the fabrial housing on her left arm. Storms. It was almost time for the meeting of monarchs. It wouldn’t do for her to be late after the number of times she’d chided Dalinar for ignoring his clock.

“See where your imagination takes you,” she repeated to Falilar. “You’ve spent years building bridges to span chasms. Let’s learn how to span the sky.”

“It will be done,” he said, taking the box. “This is genius, Brightness. Truly.”

She smiled. They liked to say that, and she appreciated the sentiment. The truth was, she merely knew how to harness the genius of others—as she was hoping to harness the storm.

***

She arrived at the meeting with time to spare, fortunately. It was held in a chamber on the highest floor of the tower, where Dalinar had made each monarch carry their own seat months ago.

She remembered the tension of those initial meetings, each member speaking carefully—anxiously, as if a whitespine slumbered nearby. These days, the room was loud and full of chatter. She knew most of the ministers and functionaries by name, and asked after their families. She caught sight of Dalinar chatting amiably with Queen Fen and Kmakl.

It was remarkable. In another time, a united coalition of Alethi, Veden, Thaylen, and Azish forces would have been the most incredible thing to have happened in generations. Unfortunately, it was only possible in response to greater marvels—and threats.

Still, she couldn’t help feeling optimistic as she chatted. Right up until she turned around and came face-to-face with Taravangian.

The kindly-looking old man had regrown his wispy beard and mustache—of a style that was reminiscent of old scholars from ancient paintings. One might easily imagine this robed figure as some guru sitting in a shrine, pontificating about the nature of storms and the souls of men.

“Ah, Brightness,” he said. “I have yet to congratulate you on the success of your flying ship. I am eager to see the schematics once you feel comfortable sharing them.”

Navani nodded. Gone was the feigned innocence, the pretended stupidity, that Taravangian had maintained for so long. A lesser man might have persisted stubbornly in his lies. To his credit, once the Assassin in White had revealed the truth, Taravangian had dropped the act and immediately slipped into a new role: that of a political genius.

“How go the troubles at home, Taravangian?” Navani asked.

“We have reached agreements,” Taravangian said. “As I suspect you already know, Brightness. I have chosen my new heir from Veden stock, ratified by the highprinces, and made provisions for Kharbranth to go to my daughter. For now, the Vedens see the truth: We cannot squabble over details during an invasion.”

“That is well,” she said, trying—and failing—to keep the coldness from her voice. “A pity we don’t have access to the military minds of the Veden elite, not to mention their best young soldiers. All sent to their graves in a pointless civil war mere months before the coming of the Everstorm.”

“Do you think, Brightness,” Taravangian said, “that the Veden king would have accepted Dalinar’s proposals of unification? Do you really think that old Hanavanar—the paranoid man who spent years playing his own highprinces against one another—would ever have joined this coalition? His death might well have been the best thing that ever happened to Alethkar. Think on that, Brightness, before your accusations set the room aflame.”

He was correct, unfortunately. It was unlikely the late king of Jah Keved would ever have listened to Dalinar—the Vedens had deep-seated grudges with the Blackthorn. The coalition’s early days had depended greatly upon the fact that Taravangian had joined it, bringing the might of a broken—but still formidable—Jah Keved.

“It might be easier to accept your goodwill, Your Majesty,” Navani said, “if you hadn’t tried to undermine my husband by revealing sensitive information to the coalition.”

Taravangian stepped close, and a part of Navani panicked. This man terrified her, she realized. Her instincts toward him were the same she might have toward an enemy soldier with a sword. Yet at the end of the day, a single man with a sword was no threat to kingdoms. This man had fooled the smartest people in the world. He had conned his way into Dalinar’s inner circle. He had played them for fools, all while seizing the throne of Jah Keved. And everyone had praised him.

That was true danger.

She forced herself not to shy away as he leaned in close; he didn’t seem to intend the maneuver to be threatening. He was shorter than she was, and had no physical presence with which to impose. Instead he spoke softly. “Everything I’ve done was in the name of protecting humankind. Every step I’ve taken, every ploy I’ve devised, every pain I’ve suffered. It was all done to protect our future.

“I could point out that your own husbands—both of them—committed crimes that far outweigh mine. I ordered the murder of a handful of tyrants, but I burned no cities. Yes, the lighteyes of Jah Keved turned on one another once their king was dead, but I did not force them. Those deaths are not my burden.

“All of this is immaterial, however. Because I would have burned villages to prevent what was coming. I would have sent the Vedens into chaos. No matter the cost, I would have paid it. Know this. If humankind survives the new storm, it will be because of the actions I took. I stand by them.”

He stepped back, leaving her trembling. Something about his intensity, the confidence of his words, left her speechless.

“I truly am impressed by your discoveries,” he said. “We all benefit from what you’ve accomplished. Perhaps in future years few will think to thank you, but I do so now.” He bowed to her, then walked over to take his seat, a lonely man who no longer brought attendants with him to these meetings.

Dangerous, a part of her thought again. And incredible. Yes, most men would have denied the accusations. Taravangian had leaned into them, taken ownership of them.

If mankind was truly fighting for its very survival, could any of them turn away the aid of the man who had expertly seized the throne of a kingdom far more powerful than his lowly citystate? She doubted Dalinar would have thought twice about Taravangian—even with the assassinations exposed—if not for one difficult question.

Was Taravangian working for the enemy? They risked the future of the world itself on the answer.

Navani found her seat as Noura—the head Azish vizier—called the meeting to order. She generally led the meetings these days; everyone responded well to her calm air of wisdom. The primary order of business was to discuss Dalinar’s proposal for making a large offensive into Emul, crushing the enemy troops there up against the god-priest of Tukar. Noura had him stand up to outline the proposal, though Jasnah’s scribes had sent detailed explanations to everyone in advance.

Navani let her mind wander, her thoughts circling around the phantom spanreed author. You must stop making this new kind of fabrial…Perhaps they meant the ones using aluminum?

Soon enough Dalinar finished his proposal, opening the floor to discussion by the other monarchs. As expected, the young Azish Prime Aqasix was the first to respond. Yanagawn was looking more and more like an emperor each day, as the rest of his body was growing into the lanky height puberty had given him. He stood up, speaking for himself in the meeting—something he preferred to do, despite Azish custom.

“We were delighted to receive this proposal, Dalinar,” the Prime said in excellent Alethi. He’d likely prepared this speech ahead of time, so he wouldn’t make mistakes. “And we thank Her Majesty Jasnah Kholin for her thorough written explanations of its merits. As you can likely guess, we needed no persuasion to accept this plan.”

He gestured toward the Emuli prime, a man living—as most of the Alethi did—in exile. The coalition had promised him a restored Emul in the past, but had so far been unable to deliver.

“The union of Makabaki states has discussed already, and we support this proposal wholeheartedly,” Yanagawn said. “It is bold and decisive. We will lend it our every resource.”

No surprise there, Navani thought. But Taravangian will oppose it. The old schemer had always pushed them to invest more heavily into the fight on his borders. The Mink had been clear in his final report; he feared Taravangian’s actions were a ploy to get Dalinar to overextend into Alethkar. Additionally, Taravangian had historically taken the role of the more cautious, conservative one in the council, and as such, had good reason to oppose committing to Emul.

The wildcard would be Queen Fen and the Thaylens. She wore a bright patterned skirt today, decidedly not of Vorin fashion, and the white ringlets of her eyebrows bounced as she looked from Jasnah to Dalinar, thoughtful. Most of the room seemed to be able to read how this would play out. Taravangian disagreeing, Azir supporting. So how would Fen—

“If I may speak,” Taravangian said, standing. “I would like to applaud this bold and wonderful proposal. Jah Keved and Kharbranth support it wholeheartedly. I have asked my generals how we might best lend our aid, and we can deliver twenty thousand troops to march immediately through the Oathgates for deployment into Emul.”

What? Navani thought. He supported the proposal?

Storms. What had they missed? Why would he be so willing to pull troops away from his border now, after a year of insisting he couldn’t spare even a handful? He’d always used the ubiquity of his medical support to cloud his miserly troop deployments.

Had he realized Dalinar wasn’t going to give an opportunity for betrayal? Was this something else?

“We are grateful for your support, Taravangian,” Yanagawn said. “Dalinar, that is two for your proposal. Three with you, and four, assuming your niece is already persuaded. The only one we await is Her Majesty.” He turned to Fen.

“Her Majesty,” Fen said, “is storming baffled. When’s the last time the lot of us all agreed on something?”

“We all vote favor for lunching break,” Yanagawn said, smiling and deviating from his script. “Usually.”

“Well, that’s the truth.” Fen leaned back in her seat. “You surprised me with this one, Dalinar. I knew you were tacking toward some goal, but I thought for sure you would insist on trying to recapture your homeland. This general you recovered, he changed your mind, didn’t he?”

Dalinar nodded. “He would like me to move that Herdaz be granted a seat on our council.”

“Herdaz is no more,” Fen said. “But I suppose the same could be said for Alethkar. I suggest that if his help proves useful in Emul, we grant such a request. For now, how do we proceed? I suspect an attack into Emul will provoke the enemy navy to finally come out and engage us, so I’ll need to plan for a blockade. Tukar has a long coast; that’s going to be a challenge. Stormblessed, I suppose we can count on Windrunner patrols to help warn us of…”

Fen trailed off, twisting around toward the small group of Radiants at the side of the room. Each Radiant order usually sent at least one representative. Taravangian’s Dustbringer was there as usual, and Lift was likely somewhere, judging from the state of the snack table—though a few other Edgedancers were sitting at the rear as well.

Normally Kaladin would be there, leaning against the wall, looming like a stormcloud. No longer. Instead Sigzil stepped forward, newly minted as companylord. It was an interesting move, elevating a foreigner—but it was a freedom Dalinar gained by no longer being directly tied to Alethkar. In this tower, ethnicity was secondary to Radiant bonds.

Sigzil didn’t have the presence of his highmarshal; he always seemed too… fiddly to Navani. He cleared his throat, sounding uncomfortable in his new role. “You will have Windrunner support, Your Majesty. The enemy air troops might not want to fly in from Iri or Alethkar, as both routes would require them to traverse our lands. The Heavenly Ones might try to loop around and come in from the ocean. Plus, they’ve been employing Skybreakers frequently in the region—so we’ll need to contend with them.”

“Good,” Fen said. “Where’s Stormblessed?”

“Leave of absence, Your Majesty. He was wounded recently.”

“What kind of wound can bring down a Windrunner?” Fen snapped. “Don’t you regrow body parts?”

“Um, yes, Your Majesty. The highmarshal is recovering from a different kind of wound.”

She grunted, looking over at Dalinar. “Well, the guilds of Thaylenah agree to this plan. If we retake Emul and Tukar, it will give us absolute dominance of the Southern Depths. You couldn’t ask for a better staging platform for eventually recovering Alethkar. You’re wise, Blackthorn, to delay striking for your homeland in favor of the tactically sound move.”

“It was a difficult decision, Fen,” Navani said. “One we made only after exploring every other option.” And Taravangian agreeing to it has me worried.

“It highlights another problem though,” Fen said. “We need more Windrunners. Kmakl has been raving about your flying fortress—I’ll have you know, I haven’t seen him this smitten since our first days courting. But the enemy has both Fused and Skybreakers, and you can’t protect a ship like that without air support. Stormfather help us if enemies in the air catch one of our ocean fleets unprotected.”

“We’ve been working on a solution,” Dalinar promised. “It is a… difficult problem. Spren can be even more stubborn than men.”

“Makes sense,” Fen said. “I’ve never met a wind or current that would change course because I shouted at them.”

Someone cleared their throat, and Navani was surprised to see Sigzil stepping forward again. “I’ve been speaking with my spren, Your Majesty, and I might be able to offer a potential solution to this problem. I believe we should send an envoy to the honorspren.”

Navani leaned forward in her seat. “What kind of envoy?”

“The honorspren can be a… touchy group,” Sigzil explained. “Many are not as carefree as our initial interactions with them led us to believe. Among spren, they are some of the closest in spirit and intent to the god Honor. While obviously individuals will vary in personality, there is a general feeling of discontent—well, insult—among them regarding humans.”

Sigzil surveyed the crowd, and could plainly see that many of them weren’t following him. He took a deep breath. “Here, let me say it this way. Pretend there was a kingdom you wanted to be our ally in this war. Except we betrayed them a few generations ago in a similar alliance. Would we be surprised that they refused to help us now?”

Navani found herself nodding.

“So, you’re saying we need to repair relations,” Fen said, “for something that happened thousands of years ago?”

“Your Majesty,” Sigzil said, “with respect, the Recreance is ancient history to us—but to the spren it was only a few generations ago. The honorspren are upset; they feel their trust was betrayed. In their eyes, we never addressed what we did to them. For lack of a better term, their honor was offended.”

Dalinar leaned forward in his seat. “Soldier, you’re saying they want us to go to them begging? If Odium claims this land, they’ll suffer as much as we will!”

“I know that, sir,” Sigzil said. “You don’t have to persuade me. But again, think of a nation your ancestors offended, but whose resources you now need. Wouldn’t you at least send an envoy with an official apology?” He shrugged. “I can’t promise it will work, but my advice is that we try.”

Navani nodded again. She’d usually ignored this man because he acted so much like… well, a scribe. The kind of nitpicky person who often created more work for others. She now recognized that was unfair. She had found wisdom in the efforts of scholars others thought to be too focused on details.

It’s because he’s a man, she thought. And a soldier, not an ardent. He didn’t act like the other Windrunners, so she’d dismissed him. Not a good look, Navani, she thought at herself. For one who claims to be a patron of the thoughtful.

“This man speaks wisdom,” she said to the others. “We have been presumptuous in regards to the spren.”

“Can we send you, Radiant?” Fen asked Sigzil. “You seem to understand their mindset.”

Sigzil grimaced. “That might be a bad idea. We Windrunners… we’re acting in defiance of honorspren law. We’d make the worst envoys, because of… well, they don’t much like Kaladin, to be honest. If one of us showed up at their fortress, they might try to arrest us.

“My advice is to send a small but important contingent of other Radiants. Specifically, Radiants who have bonded spren whose relatives approve of what we’re doing. They can make arguments on our behalf.”

“That rules me out,” Jasnah said. “The other inkspren are generally opposed to what Ivory did in bonding with me.” She glanced to Renarin, who sat at the rear of the room, behind his brother. He glanced up in a panic, his puzzle box frozen in his hands. “We probably,” Jasnah continued, “don’t want to send Renarin either. Considering his… special circumstances.”

“An Edgedancer, then?” Dalinar said. “The cultivationspren have generally embraced our new order of Radiants. I believe some of thosee who bonded Radiants are regarded highly in Shadesmar.”

True to Navani’s earlier guess, Lift emerged from underneath the table—though she hit her head climbing out, then glared at the table. The Reshi girl—well, teen—barely fit in spaces like that any longer, and seemed able to hit her elbows on every piece of furniture she passed.

“I’ll go,” Lift said, then yawned. “I’m getting bored here.”

“Perhaps… someone older,” Dalinar said.

“Nah,” Lift said. “You need them all. They’re all good at the Edgedancing part. ’Sides, Wyndle is famous on the other side on account of him figuring out how chairs work. I didn’t believe it at first, ’cuz I never heard of him before he started bothering me. It’s true though. Spren are weird, so they like weird things, like silly little vine people.”

The room fell silent, and Navani suspected that everyone was thinking along the same lines. They couldn’t send Lift to lead an envoy representing them. She was enthusiastic, yes, but… she was also… well… Lift.

“You are excellent with healing,” Dalinar said to her, “among the best of your order. We need you here, and besides, we should send someone with practice as a diplomat.”

“I could give it a try, sir,” said Godeke, a shorter Edgedancer who had once been an ardent. “I have some experience with these matters.”

“Excellent,” Dalinar said.

“Adolin and I should lead this envoy,” Shallan said. She seemed reluctant as she stood up. “Cryptics and honorspren don’t get along fantastically, but I’m a good choice regardless. Who better to represent us than a highprince and his Radiant wife?”

“An excellent suggestion,” Dalinar said. “We can send one of the Truthwatchers—other than Renarin—and one Stoneward. With Godeke, that would give us four different Radiants and their spren, plus my own son. Radiant Sigzil, would that satisfy the honorspren?”

He cocked his head, listening to something none of the rest of them could hear. “She thinks so, sir. It’s a good start, at least. She says to send gifts, and to ask for help. Honorspren have a difficult time turning away people in need. Apologize for the past, promise to do better, and explain how dire our situation is. That might work.” He paused. “It also wouldn’t hurt if the Stormfather were to speak on our behalf, sir.”

“I’ll see if that can be arranged,” Dalinar said. “He can be difficult.” He turned to Shallan and Adolin. “You are both willing to lead this expedition? Shadesmar is dangerous.”

“It’s really not that bad,” Adolin said. “Assuming we’re not being chased the entire time, I think it might be fun.”

There’s something there, Navani thought, reading the boy’s excitement. He’s wanted to get back into Shadesmar for months now. But what of Shallan? She settled down in her seat, and while she nodded to Dalinar at his question, she seemed… reserved. Navani would have expected her to be excited as well; Shallan loved going new and strange places.

Dalinar took their agreement, and the general lack of objections from the monarchs, as enough. It was set. An expedition into Shadesmar and a large military push into Emul—both plans unanimously agreed upon.

Navani wasn’t certain what to think about how easily it had happened. It was nice to make headway; yet in her experience, a fair breeze one day was the herald of a tempest to come.

***

She didn’t get a chance to voice her concerns until much later in the night, when she managed to pull away from dinner with Fen and Kmakl. She tried to make time for the monarchs individually when she could, as Dalinar was so often off inspecting troops on one front line or the other.

He didn’t intentionally ignore social responsibilities as Gavilar had done at the end—in Dalinar’s case, he simply didn’t notice. And with him, that was generally fine. People liked seeing him think like a soldier, and spoke with fondness—rather than insult—about his occasional social missteps. He was, despite having grown calmer over the years, still the Blackthorn. It would be wrong if he didn’t sometimes eat his dessert with his fingers or unthinkingly call someone “soldier” instead of using their royal title.

Regardless, Navani took care to make certain everyone knew that they were appreciated. It was left mostly unsaid, but no one truly knew what Dalinar’s relationship was with the coalition. Merely another monarch, or something more? He controlled the Oathgates, and almost all the Radiants looked to him as their superior officer.

Beyond that, many who had broken off from mainstream Vorinism were treating his autobiography as a religious text. Dalinar wasn’t highking in name, just monarch of Urithiru, but the other monarchs stepped delicately—still wondering if this coalition would eventually become an empire beneath the Blackthorn.

Navani soothed worries, made oblique promises, and generally tried to keep everyone pointed in the right direction. It was exhausting work, so when she finally trailed into their rooms, she was glad to see that Dalinar had their heating fabrial warming the place with a toasty red light. He had unalon tea for her on the heating plate—very thoughtful, as he never brewed it for himself, finding it too sweet.

She fetched a cup, then found him on the couch nearest the fabrial, staring at its light. His jacket was off, draped across a nearby chair, and he’d dismissed the servants—as he usually did, and often too frequently. She’d need to let them know—again—that he wasn’t offended by something they’d done. He merely liked to be alone.

Fortunately, he’d made it clear that being alone didn’t include being away from her. He had a strange definition of the word sometimes. Indeed, he immediately made space for her as she sat down, letting her melt into the crook of his arm before the warm hearth. She undid the button on her safehand sleeve and gripped the warm cup in both hands. She’d grown comfortable with a glove these last few years, and found it increasingly annoying to have to wear something more formal to meetings.

For a time, she simply enjoyed the warmth. Three sources of it. The first the warmth of the fabrial, the second the warmth of the tea, and the third the warmth of him against her back. The most welcome of them all. He rested his hand along her upper arm and would occasionally rub with one finger—as if wanting to constantly remind himself that she was there with him.

“I used to think these fabrials were terrible,” he eventually said, “replacing the life of a fire with something so… cold. Warm, yes, but cold. Strange, how quickly I’ve come to enjoy them. No need to keep piling on logs. No worry about the flue clogging and smoke boiling out. It’s amazing how much removing a few background worries can free the mind.”

“To think about Taravangian?” she guessed. “And how he supported the war proposal instead of objecting?”

“You know me too well.”

“I’m worried too,” she said, sipping her tea. “He was far too quick to offer troops. We’ll have to take them, you know. After spending months complaining he was withholding his armies, we can’t turn them away now.”

“What is he planning?” Dalinar asked. “This is where I’m most likely to fail everyone, Navani. Sadeas outmaneuvered me, and I fear Taravangian is more crafty in every respect. When I tried to make initial moves to cut him out of the coalition, he’d already worked on the others to undermine any such attempt. He’s playing me, and doing it deftly, right beneath my nose.”

“You don’t have to face him alone,” Navani said. “This isn’t only upon you.”

“I know,” Dalinar said, his eyes seeming to glow as he stared at the bright ruby in the hearth. “I won’t ever suffer that feeling again, Navani. That moment of standing on the Shattered Plains watching Sadeas retreat. Of knowing that my faith in someone—my stupid naivety—had doomed the lives of thousands of men. I won’t be Taravangian’s pawn.”

She reached up and cupped his chin in her hand. “You suffered betrayal by Sadeas because you saw the man as he should have been, if he’d risen above his own pettiness. Don’t lose that faith, Dalinar. It’s part of what makes you the man you have become.”

“Taravangian is confident, Navani. If he’s working with the enemy, there’s a reason for it. He always has a reason.”

“Wealth, renown. Vengeance maybe.”

“No,” Dalinar said. “No, not him.” He closed his eyes. “When I… when I burned the Rift, I did it in anger. Children and innocents died because of my fury. I know that feeling; I could spot it. If Taravangian killed a child, he’d do it not for vengeance. Not for fury. Not for wealth or renown. But because he sincerely thought the child’s death was necessary.”

“He would call it good, then?”

“No. He would acknowledge it as evil, would say it stains his soul. He says… that’s the point of having a monarch. A man to wallow in blood, to be stained by it and destroyed by it, so that others might not suffer.”

He opened his eyes and raised his hand to hold hers. “It’s similar, in a way, to how the ancient Radiants saw themselves. In the visions they said… they were the watchers at the rim. They trained in deadly arts to protect others from needing to do so. The same philosophy, less tarnished. He’s so close to being right, Navani. If I could only get through to him…”

“I worry that instead he’ll change you, Dalinar,” she said. “Don’t listen too closely to what he says.”

He nodded, and seemed to take that to heart. She rested her head against his chest, listening to his heartbeat.

“I want you to stay here,” he said, “in the tower. Jasnah wants to deploy with us into Emul; she’s eager to prove she can lead in battle. With an offensive so large, I’ll be needed in person as well. Taravangian knows that; he must be planning a trap for us. Someone needs to be here in the tower, safe—to pull the rest of us out if something goes wrong.”

Someone to lead the Alethi, in case Jasnah and I are killed in Taravangian’s trap, he left unsaid.

She didn’t object. Yes, an Alethi woman would normally go to war to scribe for her husband. Yes, he was defying this in part because he wanted her safe. He was a little overprotective.

She forgave him this. They would need a member of the royal family to stay in reserve, and besides, she was increasingly certain that the best thing she could do to help would involve unraveling the mysteries of this tower.

“If you’re going to leave me,” she said, “then you’d best treat me well in the days leading up to your departure. So I remember you fondly and know that you love me.”

“Is there ever a question of that?”

She pulled back, then lightly ran her finger along his jaw. “A woman needs constant reminders. She needs to know that she has his heart, even when she cannot have his company.”

“You have my heart always.”

“And tonight specifically?”

“And tonight,” he said, “specifically.” He leaned forward to kiss her, pulling her tight with those formidable arms of his. In this she encountered a fourth warmth to the night, more powerful than all the rest.

The End of Part One

Excerpted from Rhythm of War, copyright ©2020 Dragonsteel Entertainment.

Join the Rhythm of War Read-Along Discussion for this week’s chapters!

Rhythm of War, Book 4 of The Stormlight Archive, is available for pre-order now from your preferred retailer.

(U.K. readers, click here.)

Buy the Book

Rhythm of War