Once in college, a professor asked us to bring in selections of erotic literature to read aloud. She made a point of giving us zero parameters in this exercise; if you’d stood in front of the room and recited the warranty for a microwave, you would have received full credit. The point being made to the class was that what constituted “erotic” writing meant vastly different things to different people. We heard poems about female anatomy, sections from romance novels, even diary entries.

I read a selection from the opening pages of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray.

At face value, I suppose that sounds a little pretentious—students are coming in with visceral clitoris poetry and sexy diary entries and straight-up erotica, and there I was reading a monologue from a book over a century old that contained no mention of sex in it whatsoever. It wasn’t as though I was unacquainted with racier material either, being a devotee of fanfiction, plenty of it explicit. I could have easily brought one of my favorites in and read it aloud to the class. But when our professor asked for erotic writing, this was really the first thing that sprang to my mind:

I turned half-way round, and saw Dorian Gray for the first time. When our eyes met, I felt that I was growing pale. A curious instinct of terror came over me. I knew that I had come face to face with some one whose mere personality was so fascinating that, if I allowed it to do so, it would absorb my whole nature, my whole soul, my very art itself.

When I was younger, I didn’t know where to find any form of queer content that wasn’t fan-created. And I adored fandom, but it came with caveats, primarily around the concepts of legitimacy—I could read, write, believe that any character was queer (and I did, and I do), but everyone else in the world was permitted to scoff for its lack of “canonicity”. Subtext over text doesn’t fly with most people. When you’re busy trying to figure out how you personally relate to sexuality and gender, and subtext is what you have to go on, it sort of feels like pointing to a living gryphon in the middle of the room, shouting for the world to notice, and having everyone stare blankly at you before saying “What are you talking about? That’s just a dragonfly. A perfectly normal dragonfly.”

But in some ways, it can make subtext feel more real than anything else on this earth. Particularly once you learn that subtext is blatantly textual for an alarming number of people. And that was what it felt like to read The Picture of Dorian Gray for the first time in high school. I was taking an English elective about books and how they were translated into films—don’t ask me about the original movie, it turns into a long rant about Hollywood’s Puritanical value system being applied to stories it had no business trying to alter—but most of the class wasn’t very interested in the myriad of ways the book could be explored, nor were they interested in the author himself. Having read some of Wilde’s plays, and knowing a bit about his life, I found myself in a camp of one.

I didn’t know it at the time, but that camp was Almost Definitely The Only Queer Person in This Class.

At the time, I tried to couch this in a thorough dissection of the story, viewing it from every possible angle as though that were the only explanation for my fascination. The 1945 film (and my scathing bitterness toward it) helped me branch out in my interpretations, and there were plenty to choose from—Basil is God and Lord Henry is the Devil, and Dorian is their mortal experiment; Dorian is the ego, Basil is the superego, and Lord Henry is the terrible id; each of the central trio is a reflection of Wilde himself; the book as a critique of Victorian propriety and a social code that is more obsessed with keeping up appearances than it is with doing right. But there was another aspect of the story I wanted to discuss that no one else around me seemed to notice: the book was incredibly gay.

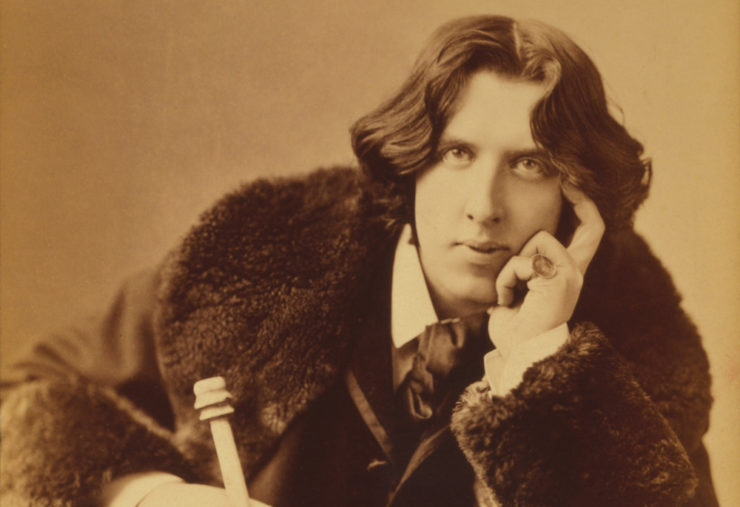

This sounds like a given to most people, I’m sure. Oscar Wilde is probably best known for three things—he was endlessly witty, he wrote The Importance of Being Earnest, and he was convicted of gross indecency in English courts, which sentenced him to years of hard labor and led to his eventual death. Homophobia and hate killed Oscar Wilde. I already knew this. Oblique references in textbooks and off-handed comments by adults and late-night viewings of Wilde on cable had taught me this. It’s extremely difficult to go through the English-speaking word with any love of literature in general, and not know that Oscar Wilde was gay and that being gay is part of what killed him.

But the other students in my class weren’t interested in that particular reading of the book. What’s more, they didn’t find the same things I found within the text. It was a lonely feeling, trying to piece together my hurt over the fact that no one seemed willing to engage with this clever and terrifying and abundantly queer book with me. It bothered me enough that I’m still thinking about it years later. It bothered me enough that I decided to write this piece, describing the importance of this book as a sort of accidental introduction to my own queerness. But as with all good stories, it doesn’t end where I thought it did, with my experience reading The Picture of Dorian Gray in high school—

—it ended just the other day, when I learned that I’d read the wrong version of the book.

Some casual research on today’s internet will inform anyone who’s interested that Wilde rewrote sections of Dorian Gray post-publication due to how scandalized the public was over its content; he had to make it less obviously homoerotic. One might assume that following his death, most versions of the book would contain his original text, as it is widely available. My copy has the words “unabridged” on the cover, which feels like a safe word, a completest word, one not inclined to mislead you. But I needed to find a quote, so I nabbed an ebook version and found myself paging through other parts of the book. Imagine my shock when the section I had read in high school as:

“Don’t speak. Wait till you hear what I have to say. Dorian, from the moment I met you, your personality had the most extraordinary influence over me. I was dominated soul, brain, and power by you. You became to me the visible incarnation of that unseen ideal whose memory haunts us artists like an exquisite dream.”

turned out to be this:

“Don’t speak. Wait till you hear what I have to say. It is quite true that I have worshipped you with far more romance of feeling than a man usually gives to a friend. Somehow, I had never loved a woman. I suppose I never had time. Perhaps, as Harry says, a really ‘grande passion’ is the privilege of those who have nothing to do, and that is the use of the idle classes in a country. Well, from the moment I met you, your personality had the most extraordinary influence over me. I quite admit that I adored you madly, extravagantly, absurdly.”

That sound you hear is my seventeen-year-old self screaming righteously at the back of the room while everyone else in the class rolls their eyes. I would like to pretend that I didn’t do this at other points in that class, but it would be lying because I was definitely That Kid.

Rather abruptly, my constant battle for reading into the subtext would seem to be won in a TKO. Here it is, in the clearest formation possible. Subject A (the altered version) is the subtext, Subject B (the unaltered version) is the text. Subject B contains words (“I have worshipped you with far more romance of feeling than a man usually gives to a friend”) almost identical to ones I told my partner when I first admitted I thought we should date. This is game over. Of course, the point isn’t that I’ve won some grand battle in the face of the literary establishment. This was always the truth—just a truth I wasn’t privy to. A truth that was being kept from me, that I didn’t have the tools to interrogate further.

And that’s important, because a sizable part of being queer is exactly this. It’s searching for yourself in words and music and theatre and often coming back empty because the world keeps telling you that they can’t (won’t) see what you see. That thing you want isn’t there, or it’s fan service, or it’s too much too fast. Things may be changing more rapidly than ever now, but that veil of persistent societal gaslighting persists. Trying to convince people is exhausting. Enjoying yourself in spite of everything can also be exhausting. Looking for evidence when you’re pretty sure that act alone makes you queer (and you don’t know that you’re ready to face up to that) is certainly exhausting.

For a long time, I told people that Dorian Gray was my favorite book. And when they asked me why, I’d usually tell them that it was because the subject matter was chilling and the prose was clever and the characters were mostly awful people, but that was interesting. These things are all true, but it was a lie where my heart was concerned. I loved the book for its subtext. I still do. And I reserve a special place in my heart for the moment in time when it came to me, as the moment we read a book is often just as important as the story itself. Timing is everything in these painfully mortal lives of ours, often more than we would care to admit.

There are many more queer books and stories out there now that have changed me for the better. But I feel I owe a particular and lasting nod to The Picture of Dorian Gray for accidentally educating me on queer experience well before I realized how much it would matter to me. Before I realized that I had a place in that kind of story, and before I was brave enough to insist upon that place. I have to guess that’s just how Oscar would have wanted it—no straightforward answer was ever worth the trouble as far as he was concerned. And in this moment, so many years after first reading the wrong version of his book… I’m inclined to agree.

Emmet Asher-Perrin needs a new copy of The Picture of Dorian Gray now, though. A prettier copy. You can bug him on Twitter, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.