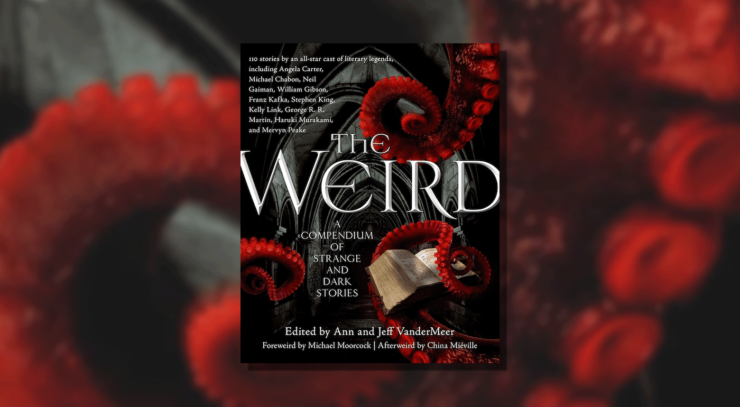

Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches. This week, we cover Liz Williams’ “The Hide,” first published in Strange Horizons in 2007. You can also find it in The Weird. Spoilers ahead!

“…I knew that come September the fog would start drifting in from the Bristol Channel, smelling of salt mud and sea, hiding first the whale-humps of islands, then the arch of Brent Knoll, then the flat lands all the way to the Tor with its tower.”

Jude has come to the Somerset Levels of southwest England to do research at Moors Centre. The surrounding wetlands were once called the Summer Country, because it was only when the winter floods retreated that the place was dry enough to negotiate. The rest of the year its marshes and groves were “the haunt only of ducks and herons, and the small people who lived along the causeways and in the lake villages.” Jude’s studies center on the Sweet Track, an ancient causeway dated to 3807 BC.

Jude opens on a cold October night. She’s searching the marshes for her sister Clare, accompanied by Clare’s boyfriend Richard. The story starts the summer before, when the three were exploring a bird reserve on the Sweet Track. Clare met Richard through a university bird-watching society, but Jude suspects her enthusiasm centers more on picnics and Richard than birds. Jude wonders what might have happened if Richard had met her before he met Clare. Experience with Clare makes her think that wouldn’t have made a difference.

Clare spots a modern wooden causeway over the reedy marsh. It leads to a bird-watcher’s hide. Clare and Richard duck inside. Near the door Jude finds the wing of a small black bird, recently torn from its owner. Impulsively she sets it on the causeway railing. The hide smells of bird droppings, though Jude sees no sign of rafter nests. Clare lifts an observation hatch, and they spot a heron. Then their focus shifts to three birds gliding over the reedbeds. They appear white, but as they pass the hide, Jude sees that they’re black, long-necked and long-beaked. Probably cormorants?

Back at the car park, they meet a man with a “hippie” van, dreadlocks, and a joint. He asks about their birding luck. They mention the cormorants; oddly, the man’s expression shifts to half-amusement, half—something else. Were these birds black or white? Black, Jude says, adding that you don’t get white ones. Sometimes you do, the man says. And how many were there? Three? Well, he hopes they don’t see them again. Before Jude can question this cryptic remark, he leaves.

Clare and Richard return north. Jude immerses herself in research. Months later, she stops at Clare’s on the way back from a conference. Clare’s out, Richard’s worried. Clare’s been moody since Somerset. Without telling him, she’s taken sick leave from work and spends her days staring into a dirty urban canal. He asks if Clare could visit Jude. Jude feels the brush of feathers against her hands; instead of crying off, she says yes.

Clare arrives in Somerset showing no sign of depression. Over tea, she confides she’s been dreaming about color-shifting cormorants. She seems disappointed when Jude shrugs the dreams off. The next day Clare doesn’t return from a walk. Jude can’t reach Richard but leaves messages. Instead of calling back, Richard arrives in person. He didn’t get Jude’s messages but dreamt about Clare wandering in a storm. In the dream he knows that if she can reach that hide they visited, they can “pull her back.” He dreams of white-then-black birds flying toward Clare: black snow starts falling and covers her. When Richard reaches her, he realizes she’s turned to crumbling peat.

Following the intuition from Richard’s dream, he and Jude go to the hide. In the January-cold October night, mist cloaks the reeds, and Richard moves like one possessed, staring straight ahead. June finds the black wing in her pocket. She’s revolted, but repockets it at Richard’s call. Strange joy suffuses his face. It’s okay, he says: Clare’s here.

Collapsed in the hide? No. Richard points through the open shutters, to a sky dawn-gray in the east, but with a red horizon and storm clouds in the west. Twenty cormorants fly across it, white when east of the hide, black when west of it. A hut on stilts rises opposite the hide, surrounded by black reeds with crimson tips “like ragged bulbs of flesh.” Clare stands on the hut balustrade. A shutter opens behind her, and in the black window Jude sees her own face, but aged and bitter. Hut-Jude waves a bloody bird wing at Hide-Jude. Then the face is no longer hers, no longer human.

Richard wades through the marsh toward the hut. As the last cormorant turns black above, Clare pulls Richard onto the balustrade. In the water, the bird’s white reflection bursts into dazzling splinters, and the hut vanishes, Clare and Richard vanish, leaving Jude alone in the night.

Jude goes home to find Richard and Clare’s things, proof she hasn’t been dreaming. The police search for the couple; the media take notice of the mystery and then drop it. Left alone again, Jude imagines an “ancient conjured hell” whose spirits she could only perceive as birds. Gradually she decides on a simpler explanation. As they went into the hide to “spy” on birds, so “something somewhere else had also set up a hide, to watch us, and when the time was right, to take.”

What’s Cyclopean: The Summer Country is rich with natural details: “gleaming wet marshes, dense beds of dull golden reeds, and groves of alder and unpollarded willow”, the better to contrast with the later, unnatural details.

Libronomicon: Both Clare and Jude had their noses in books as kids, but not the same books: Jude is all about the facts; Clare is about the myths. Jude treats this as a clear distinction, never mind kids who cheerfully alternate between Daulaire’s and National Geographic.

Anne’s Commentary

Why do people make watching birds anything from a casual hobby to a passionate vocation? I mean, why birds in particular? Amphibian and reptile watchers have a special name, but the cultural currency of herpers is so much less than birders that my spell-check always corrects it to herpes. People looking for milk-producing furry things aren’t called mammalers, nor people looking for invertebrates buggers. Here’s what separates birds from other animals: Generally speaking, they’re easier to spot and thus to photograph and add to one’s life list. Birds can be outright attention hogs—look at the garish dressers like flamingos and parrots and painted-damn-buntings! Listen to the beaks on them, chirping and squawking all day, then hooting all night. The neediest even insist on calling their own names—I’m looking at you, chickadees and whippoorwills.

Another advantage birds have in amassing followers is that they’re the only vertebrates that can fly. I’m not counting the semi-aeronautic gliders or the bats, who are unabashed bird-wannabes. Not that I discount birds who don’t fly: Penguins substitute adorable waddling and mad swimming skills, while ostriches and cassowaries can kick your ass, literally. But flight provides an escape mode the flightless can’t match if birds get any decent head-start. Granted, humans can shoot arrows or bullets, but we’re discussing only benign stalkers. Birds can safely flirt with birders, flaunting their stuff and then simply flitting away.

Sure, some birds don’t like to bask in human adulation. They dress in cryptic colors and hide in the shrubbery, shunning the paparazzi. To observe shyer targets, people need to hide as well. Shrubbery’s not always available; besides, getting into it makes big noise when you’re a clumsy biped. Birders may need to borrow hunting strategy and construct blinds. As Jude puts it, she and her companions use the sanctuary hide to “spy upon the life of birds.” The word spy implies an intentional intrusion on the gazed-upon. It’s fair that the spies should be spied in return. In Williams’ story, something is using birds as bait for its own quarry and has constructed an opposing hide from which to study them.

But—the Something will also take what it observes when the time’s right. When the season turns? When the stars align? When the portal opens between worlds?

Clare may be the sister with the “New Age soul” and an undiscerning appetite for “faux-Arthuriana,” but scientist Jude is not insensitive to the romance of the Levels. Her descriptions of the area are those of a seasoned naturalist and historian; she knows the names of things, which brings her subject landscape to life. Instead of “insects flying through flowers along the path,” she speaks of “damselflies zooming through the kingcups that grew along the margins of the dug-out peat beds.” I was inspired to look up Somerset Levels and Sedgemoor, the Sweet Track and the Moors Centre. They’re actual places in southwest England, just across the Bristol Channel from Wales. Machen celebrated the otherworldliness of the Welsh countryside. Williams brings the weirdness into Somerset.

As grounded in the mundane as Jude’s observations are, they hint at things beyond the immediately perceptible and register a subtle tremor of the strange. Williams opens with a scene that foreshadows the climax while omitting the story’s location or historical period. She then jumps backward in time to Jude’s description of the Levels. With, again, no specific period references, I was half-inclined to think her characters lived in a medieval setting on the cusp of Faery. Look at the place names: The Summer Country, the Sweet Track. Look at how she describes the Iron Age inhabitants: they are “the small people who lived along the causeways and in the lake villages.” “Small” as in fairies or imps?

Williams sets aside this ambiguity midway through a paragraph. Jude, Clare, and Richard turn out to be college-educated moderns. The Moors Centre has a carpark. The local hermit-visionary lives in a motor-van. From the Sweet Track, you can hear distant automobile traffic. You can hear it, that is, until you venture onto the causeway and approach the antechamber between our sphere and Somewhere Else. The hide still provides National Trust information sheets and a common blue heron. But to Jude the heron seems “alien, predatory, as startling as a pterodactyl,” and birds—cormorants?—first look gull-white, then crow-black, all in the space of a veer from light-effect to light-effect, or from reality to reality. Jude has already picked up a severed bird’s wing in ill-omen black. The carpark Merlin hopes they’ll never see those cormorants again. Back home Clare dreams about color-shifting cormorants and skips work to haunt a murky ship canal. Worried, Richard asks Jude to let Clare visit again.

It’s a tough ask for Jude, given she’s attracted to Richard and envies Clare’s relationship. Agreeing, she senses feathers brushing her hands: another ill omen? If so, the third omen comes when Richard and Jude hunt for Clare along the Sweet Track and Jude finds a severed black wing in her pocket. It could be a key to the Otherside, but a reverse one that locks her out instead of admitting her. It’s Clare the Othersiders want, and Clare who is Richard’s ticket in. The face Jude sees in the Other Hide’s window is her own, aged and bitter. It’s the mirror-mask the Othersider wears to mock future Jude, bereft of both sister and love interest.

The second face the Othersider shows is inhuman. I take this as a final hint the creature is Fey, because can any fairy resist getting a final jab in on us mere mortals by showing its true self?

Not in my experience anyhow.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

My birding strategy is to follow actual birders around—mostly my wife—and look where they point. I appreciate birds, but lack the particular sort of attention that lets me track feather color and beak shape and tail length and wing movement and put them all together into recognition, for anything much more challenging than a cardinal. (I am not good at this with humans either.) Birders, though, are constantly scanning for the snatch of song or flash of color that tells them that, if they just look a little closer, they’ll find something remarkable.

It seems like a useful skill for noticing that you’ve slipped out of our familiar reality into something stranger. Useful, and perhaps dangerous. After all, if you keep your head in the clouds or your phone, you might just walk right through violations of natural law none the wiser. The fewer the contents of your awareness, the lower your risk of correlating those contents, right?

Alexandra Horowitz’s On Looking illustrates the way that our attention shapes our reality. She takes 11 walks around the same block of New York City: with her dog, her toddler, an entomologist, an expert in the relationship between gait and health, et cetera. Some walks are long and some brief, some draw meaning from passers-by or buildings and others from cracks in the sidewalk or bits of trash. Bits of world appear and vanish like magic. Or like the Summer Country, ostensibly revealed by seasonally retreating waters but named like a Brigadoon, a Faerie, that only touches our world on special occasions.

Clare’s “New Age soul” seeks the numinous. Unfortunately for her, what’s out there to be revealed is no Camelot. Or so we assume. It doesn’t feel like a Camelot. But those of us who stay behind the Hide slats get only a glimpse. My first thought is some archetypal savage past, like the little house in Benson’s “Between the Lights”. But then there’s Jude’s face, older and bitter, peering from the house—so not exactly the past. Unless we’re in Charles Dexter Ward territory, made vulnerable by similarity to unpleasant ancestors. More likely, perhaps, some sort of mirror universe doppelgangers—or the extradimensional birdwatchers and birdhunters that Jude imagines, using mimicry as one of their less effective techniques.

Or maybe that really is Avalon over there, apple-groved Isle of the Dead. That would certainly be the best option.

One way or another, poor Jude is stuck in one of Clare’s books of myth, far from the realm of facts about peat bog archaeology. Even beyond the disappearance of her inconvenient crush object and her sister-rival, this is not a situation likely to submit to explanation. The color-shifting birds, the black wing still fresh with gore, the draw of the canal, Clare’s dreams and Richard’s, the Hide itself—the numinous is too close to avoid regardless of how carefully you keep your head down.

Peat bogs are liminal spaces even when not cut off by water three seasons of the year. They preserve bodies and nurture new growth. Life and death, growth and decay, change and stasis. They’re natural, but they don’t necessarily feel that way. The initial description walks that line, making the area “the haunt” of ducks and herons and lake villagers. Birds are natural, right? Just ask Du Maurier. Or ask Blackwood how quickly the natural can blur into the super-natural.

I haven’t asked my wife yet how to ID birds that shift color depending on viewing angle, or how to safely handle their feathers. Maybe I should. For now, I think, I’m going to stick to watching chickadees at our winter feeder, and go inside if they show a taste for anything other than birdseed.

Next week, there are probably more disturbing revelations in chapters 27-28 of Max Gladstone’s Last Exit.