Note: Some spoilers for the series.

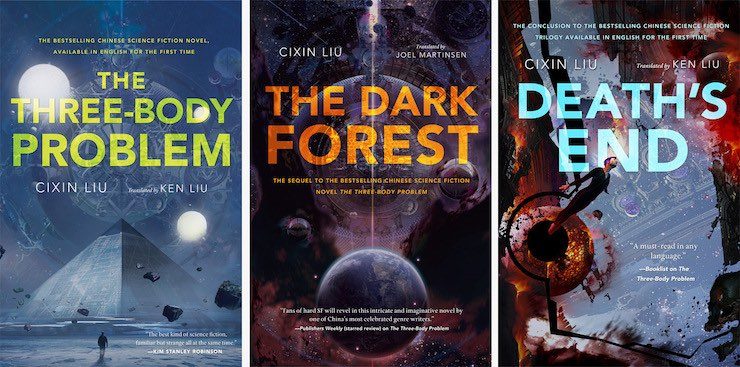

I know, that’s a pretty ambitious title for this lil’ old essay, but Cixin Liu insists that we think seriously about such questions as humanity’s future in the universe and contact with intelligent alien species. In The Three-Body Problem, The Dark Forest, and Death’s End, he weaves a complicated web of physics, philosophy, and history that take us from China’s Cultural Revolution in the mid-20th century through to the end of the solar system and beyond. Add to that the grandeur of Liu’s prose, translated so deftly into English by Ken Liu and Joel Martinsen, and it becomes clear just what a masterpiece Remembrance of Earth’s Past really is.

Like Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, Remembrance of Earth’s Past is a work of nostalgia tinged with regret. The latter is positioned as a look back at what, in reality, is one possibility for humanity’s future. Liu does this kind of thing throughout the series: he moves us readers back and forth in time and space (and dimensions), almost like he’s limbering up our brains as if they were brittle rubber bands.

And he has a point. In his postscript to The Three-Body Problem, Liu encourages us to move beyond our calcified ideas about our place in the universe and really consider what we want when we express interest in encountering alien species. The rush of excitement when humanity actually makes contact in The Three-Body Problem is short-lived; the rest of the series deals with the (often negative) ramifications of that contact. It is this pressure, though, that gives birth to some of humanity’s greatest achievements.

In the world of this series, the fallout of contact becomes the story of humanity. Given humanity’s relatively short time (so far) on this planet, the four hundred years that Liu’s characters have to prepare for the coming of the Trisolarans is quite generous. Even then, squabbling and power-grabs (along with Trisolaran technology) interfere with the need to come up with a clear plan for Earth’s first encounter with Trisolarans. This is precisely Liu’s point: that it’s reckless to try and contact alien species when a) we don’t even have our own house in order and b) we have to assume that other intelligent life in the universe is actually hostile. And why not? If you’re wandering around in a dark forest, do you really want to take the chance and expose yourself to those who might want your stuff or just one less potential threat?

Liu goes further than simply forcing us to think beyond our own planet and consider our wider galactic neighborhood; with Death’s End, he expands our perspective even further, introducing universes of two and even four dimensions. He asks us to think about (and shudder at) the existence of a disembodied brain being studied by Trisolarans for what might seem like an eternity. And then, as if our minds weren’t already reeling, he pushes the boundaries even further, asking us to think about our universe’s relation to other universes.

But what will stay with me long after this series’ appearance in English? The (sometimes devastating) grandeur of certain scenes: the slicing of the ship as it passes through the Panama canal, the destruction of the Earth fleet by the Trisolaran fleet, the flattening of the solar system (!). Liu has managed to convey the necessity of sober, intelligent thought when it comes to looking beyond our planet by offering us a grand story that brings us to the edge of our seats. (I don’t know about you, but I definitely had no fingernails left after each book).

So why would Cixin Liu embark on this mission? As he wrote in an essay for Tor.com in 2014, “I wrote about the worst of all possible universes in Three Body out of hope that we can strive for the best of all possible Earths.” This, after all, is what great speculative fiction strives for: the ability to make us consider possible futures in order to better ourselves in the present, and thus bring about a future worthy of our best selves.

Rachel S. Cordasco earned a Ph.D in Literary Studies from the University of Wisconsin, Madison in 2010, and taught courses in American and British literature, and Composition. She has also worked at the Wisconsin Historical Society Press. A Book Riot and SF Signal contributor, Rachel recently launched a site devoted to speculative fiction in translation. You can follow her @Rcordas and on facebook at Bookishly Witty and Speculative Fiction in Translation.