As the 1970s progressed, the mood in the Disney animation department could be best described as glum. The company’s attention had been steadily moving away from animated films since the late 1950s, and the death of Walt Disney had not helped. The beautiful, intricately detailed animated films had been replaced with a series of largely mediocre ones, with even the most entertaining—The Jungle Book—containing nothing even close to the innovative art of Pinocchio or even Alice in Wonderland. Disney’s animation department was no longer making, or even trying to make, great films: they were creating bland kiddie entertainment, and on a tight budget at that—so tight that animators were forced to use multiple recycled sequences and even copied animation cels in Robin Hood. The Nine Old Men—the major Disney animators that had been at the studio since Snow White—were getting close to retirement.

They needed some sort of rescue to even try for a recovery.

They needed The Rescuers.

Let me just state, from the outset, that The Rescuers is not a great film. It’s many other things, but not great. But it did, for the first time since Walt’s death, offer the hope of something new – the idea of an action oriented cartoon feature. Astonishingly enough, in 22 full length animated films, Disney had never tried this. Nearly all of the films, of course, had contained action of some sort or another—the dwarfs chasing the Evil Queen in Snow White, the hunting sequences and the forest fire in Bambi, those poor little mice tugging that key up the stairs in Cinderella, Peter Pan and Hook’s sword fighting in Peter Pan, and so on. But the action had always been a subplot at at best. From the outset, The Rescuers was something different: meant more as an action-adventure film in the James Bond mold, interrupted here and there by sugary songs, again in the James Bond mold, only with a lot less sex and more mice.

That focus came about largely because of issues with the source material. Disney had been toying with the idea of making a movie based on Margery Sharp’s novels since the 1960s. The first novel in that series, however, presented several adaptation problems, starting with the issue of pacing. The Rescuers contains several long stretches (in a very short novel) where nobody really does anything. Realistic, but from a cinematic prospective, not overly entertaining. Walt Disney also objected to the politics and international focus found in the source material. By the 1960s, somewhat burned by reactions to more serious films, he wanted light, family friendly stuff. He may have had another, unconscious, unstated motive: the novel is largely about a pampered, sheltered, very feminine mouse leaving her home for a job in spycraft and rescue. That was against the message Walt Disney was trying to send in his other films—most notably Mary Poppins—and may have been one of the factors that caused The Rescuers to languish in film development for years.

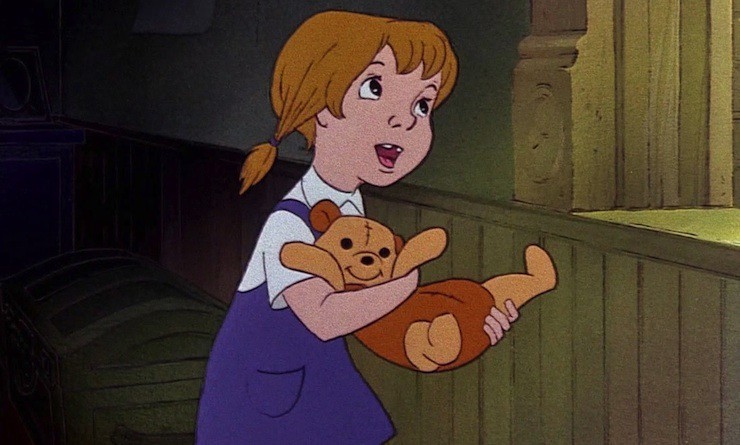

By the 1970s, however, the idea of a lady mouse who was also a more than competent action hero and spy was exactly what Disney was looking for. Oh, the idea needed tweaking—a lot of tweaking. The Miss Bianca of the film is considerably more adaptive, resourceful, independent and knowledgeable than her book counterpart, if equally elegant. Also, the plot needed tweaking—a lot of tweaking. The mice would, for instance, no longer be trying to rescue a poet—might as well leave poets in prison—but instead, a more sympathetic little girl and her teddy bear. The mice would no longer need to depend on human forms of transformation, or even forms of transformation made by humans—even elaborate toy sailboats stocked with the very best sugar. And the mice really needed to be joined by other animals—including a turtle/tortoise, which had managed to gain laughs from audience for years.

Also this all needed to be kinda like a James Bond flick.

With alligators.

With that all set up, the Disney animation team only had one real question left: Can two little mice, however educated and sophisticated, save a little girl and her teddy bear? Can they? CAN THEY?

Well—spoilers—this is a Disney film, so the answer is yes, especially if they are superstitious but practical Bernard, who sounds suspiciously like comedian Bob Newhart, right down to the dislike of flying, and Miss Bianca, who sounds and looks suspiciously like Eva Gabor, right down to her focus on luggage. The two are attending an emergency meeting of the Mouse Rescue Aid Society, located in the basement of the United Nations building in New York City. Also at the meeting are mice representatives from Latvia, Morocco, France, Hungary, China, various Arabic nations, and several other countries around the world, including one mouse representative from “Africa,” speaking for that entire continent. Let us move on, and instead look at the wall, which has a Mickey Mouse watch on it. (Pause the DVD.)

The Society has just received a message from Penny, a pathetic, overly cute, grating child that I wish we didn’t have to mention ever again, but we do, who is in need of rescue. Unfortunately, Penny has failed to give any useful information like, WHY DOES SHE NEED TO BE RESCUED, and WHERE DOES SHE NEED TO BE RESCUED, and since I already know this is the New Orleans area, I am kinda at a loss to explain how a bottle got from New Orleans to New York City without getting found by someone else, or another group of mice, but never mind. It’s one of many many plot holes that we shall just need to deal with.

Miss Bianca and Bernard are (mostly) undaunted by this issue, and set out to investigate. It helps that they like each other—well, really, like like each other, though neither has said anything out loud, since they are, after all, professional mice rescuers. Standards must be maintained, even if—I must be truthful—Bernard does slip an arm around Miss Bianca when given the opportunity. She doesn’t seem to mind. She even—I still must be truthful—snuggles up to him every once in awhile.

In the middle of all of this failure to declare their inner-mice feelings, Miss Bianca and Bernard discover the truth: after running away, Penny was captured and taken to the New Orleans area by Madame Medusa, who needs a child small enough to be able to squeeze through a hole and obtain a huge diamond left there by a dead pirate. This raises a lot of questions, none of which get answered:

- Why did Madame Medusa need to come all the way to New York City to find a small child? Was New Orleans completely devoid of small children in the 1970s, and if so, wouldn’t that have been an even more entertaining film?

- If finding this diamond is so important to her, why on earth has she gone back to New York City and left the task to be supervised by her incompetent goon and two alligators? Her predecessor, Cruella de Vil, had a reason for using goons—she was already under suspicion for Puppy Kidnapping, and needed to establish an alibi. The only people who suspect Madame Medusa of anything are the critters in the swamp, and they just suspect her of being mean.

- Why didn’t she—you know—just get a drill and just widen the hole? Or try blowing it up? We later discover, after all, that her goon has access to multiple fireworks—enough that he can even spell out letters in the sky. Under the circumstances, I find it difficult to believe that neither of them could have picked up additional explosives to widen the hole.

Bernard and Miss Bianca don’t have time to ask any of these questions, because they have to go be in a car chase. That goes excitingly, and badly, forcing them to fly down to New Orleans, which requires taking an albatross. I have no idea why they can’t just slip on a plane (as in the books), except that this would have deprived us of the albatross and his questionable takeoffs and landings, a definite loss. Then it’s off to the swamps, a rescue, and an exciting chase scene that bears a very suspicious resemblance to several James Bond flicks, plus a bit where someone waterskies on the backs of alligators, and arguably the film’s best moment: a sequence involving the mice, a pipe organ, and the alligators.

More or less driving the plot is Madame Medusa, loosely based on Cruella de Vil—they even drive the same sort of car—and, legend claims, also loosely based on animator Milt Kahls’ very much ex wife, something we’ll skip over here. She’s amusing, but like any copy, not quite up to her original. Part of the problem is that her greed doesn’t extend to, well, killing puppies—sure, what she’s doing to Penny is pretty awful, but there’s an actual chance that she does intend to just let Penny go once she has the diamond. Or, admittedly, feed the kid to the alligators, but I’m kinda in favor of that, so I’m willing to let that go.

Also driving the plot is Miss Bianca’s deep and genuine compassion. It’s not—as the film admits—a usual job for a lady mouse, but Miss Bianca is not one to stand by when someone is in trouble. The more she hears about Penny’s problems, the more desperate she is to help, motivated out of pure kindness. It’s not all compassion—Miss Bianca, it turns out, rather likes adventure and flying, even if albatross flight more resembles a theme park ride than the sort of elegant travel that she would seem to be more suited for. But it’s mostly compassion, and really, only compassion can explain why Miss Bianca still wants to save Penny even after she’s met the kid, in one of many examples proving that Miss Bianca is a much better mouse than many of us.

Not that many viewers could probably notice, given all of the roller coaster flying, sneaking into buildings, investigating mysteries, and wild chase scenes, but The Rescuers also had the first major development in animation technology since One Hundred and One Dalmatians: finally, the xerography process, which had initially created cels with thick black lines (and still visible original pencil marks) could handle grey lines and even—in limited ways—color. As a result, thanks to a combination of characters now once again animated in color, and swamp backgrounds that were the richest, most detailed Disney had done in at least a decade, the film had an almost old, classic look. At times. The detail had still not returned, and Disney did resort to using recycled animation sequences again, but it was a distinct improvement over The Jungle Book, The Aristocats, and Robin Hood.

That and the action focused plot were enough to bring in audiences, bringing in $71.2 million at the box office—Disney’s first genuine animated success since The Jungle Book, and good enough to justify Disney’s first animated film sequel, The Rescuers Down Under, more than a decade later. A later video release caused a bit of gossip and fun since unknown to Disney, someone had inserted a few shots of a topless woman into one scene. Disney hastily cleaned up the shots and released the video again; the gossip may have helped increase sales.

It also had one long term benefit for the studio: Disney used the film to have the Nine Old Men train up new animators, most notably Glen Keane, who worked on Miss Bianca and Bernard, and would later animate/supervise iconic main characters Ariel, Beast, Aladdin, Pocahontas, Tarzan, and Rapunzel; Ron Clements, who would later shift from animating to co-directing, with John Musker, seven animated Disney films (with number seven, Moana, currently scheduled for a March 2016 release); and Don Bluth, who would later form his own animation studio.

But apart from training up new animators who would later help create some of the greatest animated films of all time, and its financial success, somehow The Rescuers never seemed to make much of a long term impact on the studio. Perhaps because it was associated with director Wolfgang Reitherman, who by this time had been associated with many of Disney’s lesser films and outright flops. Perhaps because, despite the adorable mice, The Rescuers, was an uneasy fit into the Disney canon. It offered no real moral lessons apart from, perhaps, don’t be greedy, and don’t hide in a pipe organ when alligators are after you. It ended on a touch of a cliffhanger. The villain’s motive was, well, weak. It could hardly be called deep, or thoughtful, and it could not compete with Disney’s greatest classics.

Still, it’s arguably the most entertaining of the Disney films made during its animation doldrums—the period between Walt Disney’s death and Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Depending upon your love for The Jungle Book, it may even be the best of the Disney films released after One Hundred and One Dalmatians until Who Framed Roger Rabbit. And, perhaps most importantly, it allowed the animation department to stay in operation and even greenlight its most ambitious film yet, The Black Cauldron.

That film, however, was going to take years to complete. In the meantime, to stay in the animation business, Disney needed another quick, relatively simple film. They settled on The Fox and the Hound, coming up next.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.