Lucas Pope’s Return of the Obra Dinn has a highly original premise : in the year 1807, an insurance adjuster is tasked with investigating the Obra Dinn, a washed-up East Indiaman missing since 1803 and whose sixty-man crew is now dead or gone.

How? With the “Memento Mortem”, a mysterious watch that lets you travel back in time to the last few moments before death. With proximity to a body, you can hear a few seconds previous to, and see in tableau, the very instant of their demise. How wonderful, I thought. A grisly corpse-activated Time Turner! A VR Alethiometer, one that is neither obscure nor has a go at you for being Catholic!

A couple days later I was jubilant over the future of what game narrative could do for SFF. Simultaneously, and not unlike the Obra Dinn herself, I was a wreck.

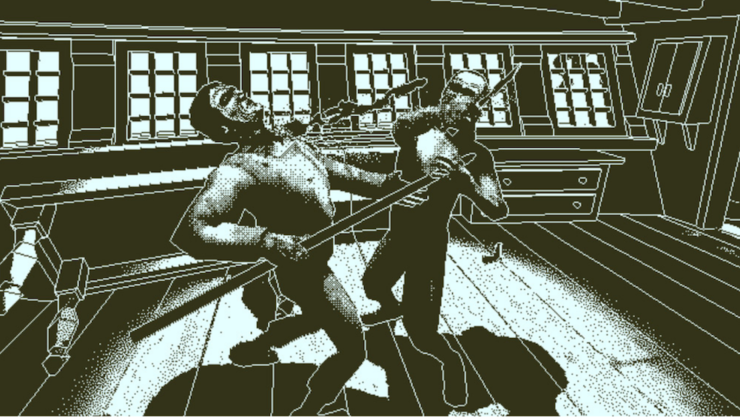

Return of the Obra Dinn requires no reflexes, nor quick thinking, nor aim. You’re playing what boils down to a giant Excel spreadsheet. It pits your brain against a pile of misdirection, confusion and error, and to win is to look at a body and figure out in the moment of death what actually caused its demise. (This is significantly more difficult than it sounds. My friend, up-and-coming author I won’t out here but whose name sounds like AK Warkwood, summed it up thus to me in an email: ‘We spent the whole of yesterday evening staring fixedly at a cluster of blurry grey pixels murmuring things like “is THAT the bosun?”’)

I’m about to fundamentally spoil it, and so, even if you’re not a gamer, and even if you hate games, and even if you don’t own a computer and as we speak you’re reading this via semaphore or something, you ought to play it. Anyone with an interest in science fiction, fantasy and horror should play it. Anyone who’s read Patrick O’Brian should play it. Anyone who’s interested in narrative should play it. As I write, it is thirty bucks NZD on Steam; that’s fifteen quid, or a little over twenty American dollars, and it’s worth every penny. Go now. Play it through. I’ll wait.

You’re back? Wonderful. Are you a gibbering shell?

Buy the Book

Gideon the Ninth

I ask this in the anticipation of nope. None of my friends seemed to be as frightened by Return of the Obra Dinn as I was. It hit me where I live. I have been accused of writing a very gory book about all the awful things that can and do happen to the body—Gideon the Ninth, the first book in my necromantic trilogy, comes out in September, and a magical corpse watch that can show you how someone died is a concept that I’m furious I didn’t come up with first—but playing Obra Dinn threw my heart rate out so bad that my fitness tracker is still convinced I was getting exercise.

This didn’t happen to any of my friends and loved ones—

FRIEND 1: These boys! Oh, these boys, they’re dyin’!

LOVED ONE: They’re not going to fix THAT guy any time soon!!

ME: Too long have I mocked Death. My body is a sack of delicate gravy; I could meet my doom at any moment. I could fall down the stairs. An enemy might stab me. The world is a foggy bestiary of me-hungry monsters. I have thus far written in a very cavalier way about murder and the end, and now I know that as I have flouted the Reaper, so too shall the Reaper flout me.

FRIEND 2: There’s barely half of that seaman left!!!

LOVED ONE: Okay, so, my assumption was that it should take the genitive and be ‘memento mortis’, but I’ve looked it up and even Virgil used the accusative sometimes. Who’d have thought.

FRIEND 1: Did the purser die from going ‘splat’, or from going ‘boom’? It could have been either

Lucas Pope’s previous game, Papers, Please!—a game about how bad it is to be a border officer under a despotic authority, which I did not play much of because I can imagine how bad it is to be a border officer under a despotic authority and also the time constraints stressed me out—was a big favourite of people I deeply respect. I imagine it’s due a revisit. As a game it was grim, but did not fill me with nerveless terror. Return of the Obra Dinn had me in the kind of nonsensical welter normally only found in Lovecraft narrators.

Lovecraft isn’t a bad evocation, honestly. The ill-fated journey of the Obra Dinn is given to you in temporally dislocated chunks—the first episode you’re directed toward is the last gasp of its crew, for instance—and you are never given the full story: Pope’s too clever in his narrative for that. From the first to the last, you are given more questions than are ever answered. A few things are clear from the outset: the Obra Dinn leaves London for the “Orient”, carrying cargo and passengers identified as being “Formosan” royalty; it makes it as far as the Canary Islands before it turns around, seemingly to sail back to England. The ship makes it back—but by that point, anyone left on board is a bunch of mysterious bones.

And I love bones. Everyone who knows me knows this. But the bones aren’t the scary part; they are just often sad little heaps left in suggestive places. The horror in Obra Dinn is the fear of the sea, which in the year 1803 is also the fear of outer space, the fear of the depths and of the unknown, the fear of the natural world. It’s also fear of the ways in which a domino effect of greed and misery can cause any human endeavour to end up as I secretly worry the whole human race will end up: found by some entity wanting to count the material cost, examining at critical angles the whole lot of us with our bony hands clutched around the knives rusting in each other’s ribcages as it ticks the box Yes for Is It A Shame.

At first it seems the only fantastical element in Obra Dinn is your magical death watch, which, sure, is a big speculative element but also possibly forgiven in game space—it’s just a mechanic, you might think. Perhaps what we are about to be presented with is nothing more than a wet, brain-spattered catalogue of explicable human folly. We all know life on board ship in the early 1800s had comparisons to the Australian Transport Authority video Dumb Ways to Die. It becomes clear very early on in the piece that the Formosans are carrying a carefully guarded treasure; that this treasure has been found a little too desirable by others on board the Obra Dinn; this one’s a tale as old as time, and you’re forgiven for thinking you know how it goes.

You do not.

(Admittance: my reaction on first being confronted with this thing was a gentle piss of terror. I cannot tell you how much worse it is in close-up.)

At first you don’t even want to notice the first supernatural elements of Obra Dinn; the Kraken’s tentacles are popping up at you in pretty much the third death you are directed to investigate, but if you’re anything like me you didn’t even bother to look at it, because you’re given a ship’s deck battered in a howling storm and someone dying, in a relatively pedestrian fashion, when a mizzen mast clonks them on the skull. Oh damn, you say, looking very carefully at the mizzen mast clonking them on the skull, noting down in your little book [STRUCK] and [BY FALLING RIGGING]. Over your head, you have not bothered to look at a huge-ass sea tentacle lifting a topman into the air. You’re too busy triumphantly saying to yourself, “I think this clonkee is the first mate’s sister!”

But the speculative elements are what make the narrative electric. They arrive like a slap of salt water to the face, and place the ocean firmly as a mindful antagonist. The ocean has been calmly killing off humans in a wild and wonderful variety of ways since we first waddled out into its shoals. It drowns us. It starves us. It chomps us, or suckers us, or smashes our boats. And it does so with a mindless, unmalicious lack of thought; the ocean is just the ocean. There is a reason why the ancient Greeks named the whirlpools in the Straits of Messina as twin sea monsters, Scylla and Charybdis: part of SFF is to take our anxieties and give them tentacles. SFF is almost a relief to the mind. You can curse a monster; whirlpools are just goddamned whirlpools.

Game writing has finally been added to the list of categories one can win a Nebula for. People have argued against the inclusion of game writing for years; there are, it was pointed out, many awards for game writers, among them a damn BAFTA. Why is it so important that SFF recognises its SFF game-writer brethren?

Because the awards should be given, in my mind, for things that make us recognise what science fiction and fantasy can do. They should be given for those things that make people say, “Yes, more of that.” Return of the Obra Dinn wouldn’t survive without its speculative elements, and indeed, uses them so cleverly and neatly to tell a subtle, anachronic narrative of man’s inhumanity to man and also mermaid’s inhumanity to man that it cannot but be lauded for it.

The quality of game writing in the industry is very uneven right now. It is a very different skillset than the one required to write a novel; this is the year where I have made a jump into writing games professionally rather than turning out endless private IF games where I bump about sexily in a witch’s house, and I am having to recalibrate everything I ever thought about narrative. But these strictures—as unmerciful as poetic metre—can produce astonishing results. I applaud Pope’s writing for its tightness and care in giving the reader exactly the right amount of information; I applaud his ability to give sympathy and take it away in the space of a few words; I applaud his originality together with his obvious care taken over salty old sailor stories. Those interested in the craft of the short story should play Obra Dinn. Look at every tiny scene as a micro-story, and see how much Pope is giving you. Listen and watch. He is being very deliberate.

I didn’t trust this deliberation at first. I thought he couldn’t possibly be this clever or this careful. I would have had a much easier time working out the identities of four particular sailors had I just put my trust in Pope and realised that he would never show me anything without cause—again, something I can only aspire to in my short-form work—rather than dismissing a scene’s details as noise. I now take pleasure at looking back to Return of the Obra Dinn and giving greater consideration to everything said or depicted or sounded. I mean, I also take no pleasure in it whatsoever, because there are two giant crabs with what appear to be backwards-headed human figures with lights in their eyes and forms swamped in seaweed, and they act as the dread soldiers of the abyss and they WILL come out of the water and they WON’T die, but that’s my unique foible. Everyone around me seemed unaffected. I’m the only one in my social circle who now sleeps clutching a harpoon.

You can only shade in the final act of the Obra Dinn if you perfectly identify every single corpse on board and how they met their sticky end. Then you’ll get one last look at what happened, specifically the events that took place within that cursed lazarette, and they will not spell out exactly what the story was but may give you new theories. Pope has been deliberate here, too. On reflection, I find the last words you will hear on board the Obra Dinn melancholy and horrifying and beautiful, just as the game itself was:

Herre, min Gud!

Or, as the game renders it: God in Heaven!

Return of the Obra Dinn shows us that if we’re not sure there are angels in Heaven above, there are certainly demons down under the sea.

Or, as The Simpsons so epigrammatically put:

Yarrr, I hate the sea and everything in it.

Tamsyn Muir is a horror, fantasy and sci-fi author whose works have appeared in Nightmare Magazine, F&SF, Fantasy Magazine, Weird Tales, and Clarkesworld. Her fiction has received nominations for the Nebula Award, the Shirley Jackson Award, the World Fantasy Award and the Eugie Foster Memorial Award. A Kiwi, she has spent most of her life in Howick, New Zealand, with time living in Waiuku and central Wellington. She currently lives and teaches in Oxford, in the United Kingdom. Gideon the Ninth is her first novel.