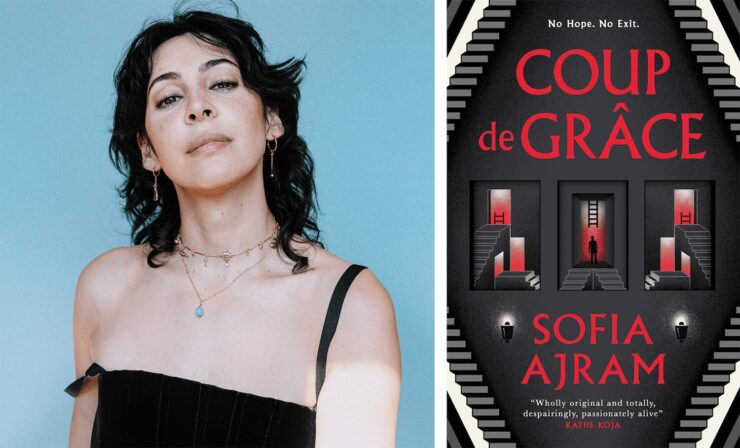

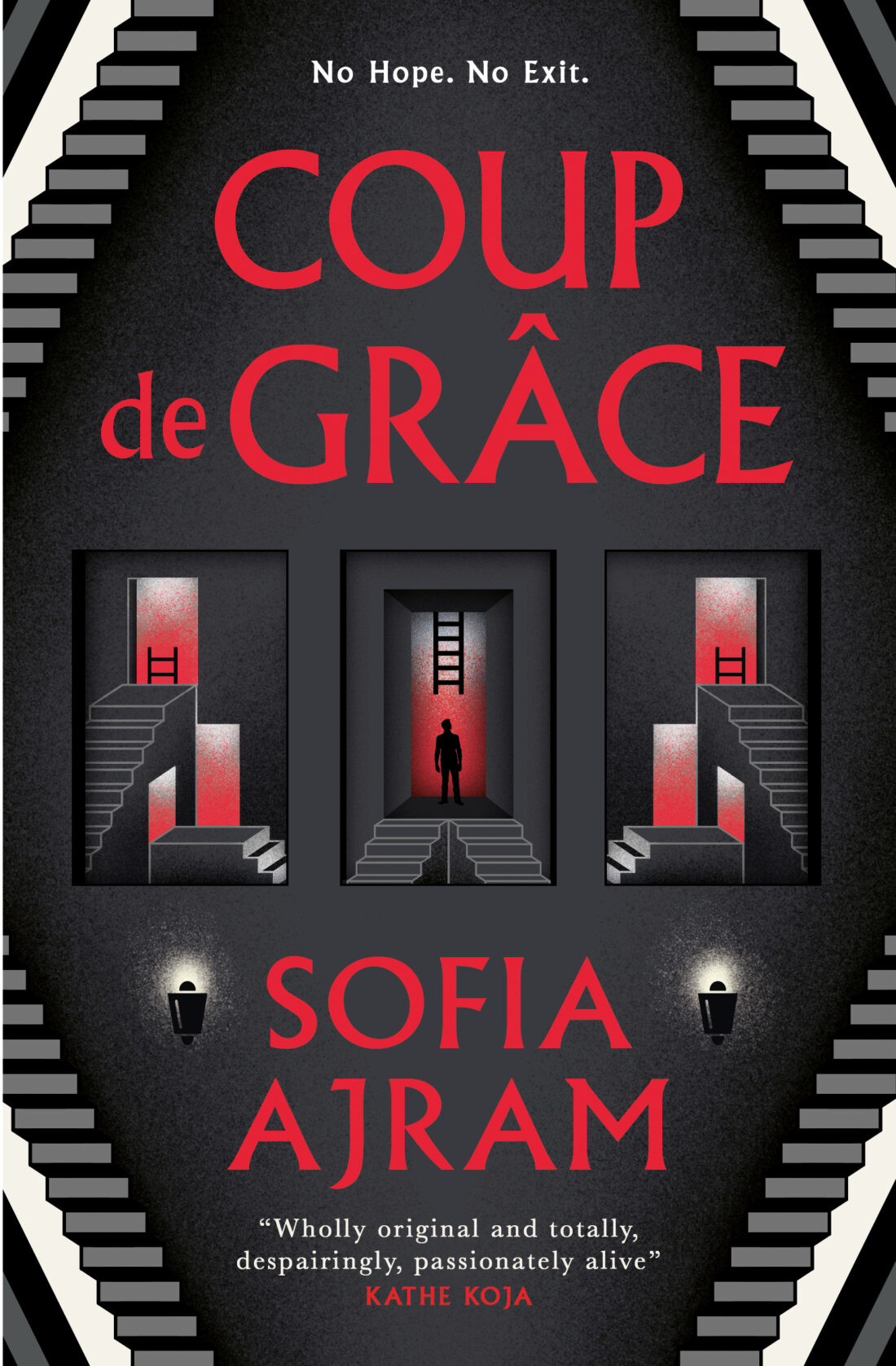

We’re thrilled to share the cover and preview an excerpt from Sofia Ajram’s Coup de Grâce, a horror novel about a young man trapped in an infinite Montreal subway station—forthcoming from Titan Books on October 1, 2024.

Vicken has a plan: throw himself into the Saint Lawrence River in Montreal and end it all for good, believing it to be the only way out for him after a lifetime of depression and pain. But, stepping off the subway, he finds himself in an endless, looping station.

Determined to find a way out again, he starts to explore the rooms and corridors ahead of him. But no matter how many claustrophobic hallways or vast cathedral-esque rooms he passes through, the exit is nowhere in sight.

The more he explores his strange new prison, the more he becomes convinced that he hasn’t been trapped there accidentally, and amongst the shadows and concrete, he comes to realise that he almost certainly is not alone.

A terrifying psychological nightmare from a powerful new voice in horror.

Sofia Ajram is a multidisciplinary artist based in Montreal and the designer of Sofia Zakia jewelry. They are a moderator for the Horror and HorrorLit forums on Reddit and have given lectures on contemporary horror films at Monstrum Montreal. Their latest project, Bury Your Gays: An Anthology of Tragic Queer Horror (serving as Editor) releases March 2024. He is an Active member of the Horror Writers Association, and Ethical Metalsmiths. Sofia lives in Montreal with her cat Isa.

Where my feet step off, groggy and mired in confusion, there are no station plaques, which is funny, because that’s not a place that exists, like some twisted Black Lodge or LesterCorp Floor 7 ½, and while I’m thinking about these things and the wry humour of them, the subway chimes, the doors behind me glide shut, and with a puff of air, like a rising gale, the train plunges down the track into the black maw and vanishes into the void.

When I spin around to face the tracks, they are empty. A thick yellow stripe lines the length of the platform, denoting the edge. There is a trench where the tracks lie, though no visible outbound tracks that I can see. A few stations are like this in Montreal, namely De L’Eglise and Charlevoix—the deepest station in the network—where platforms are constructed with narrow access points folded one on top of the other rather than side-by-side. There is no natural illumination, only the incandescent glow of fluorescent lights crawling along the platform overhead like a millipede. The smell is that of old buildings: wet concrete: dark and damp and dense; the sound of it, the whispered mono-frequency of aircraft white noise, of liminal thresholds between continents.

I look sidelong down the platform. It is empty.

Buy the Book

Coup de Grâce

I glance at my phone. No missed calls, no texts. No bars. It’s late, and I can see that I’ve overslept; wasted precious time. I creep onward and bound up the stairs at the end of the platform in twos. There’s only about thirteen steps, and then a short landing which rotates and leads to a second set. At the summit is a floor-to-ceiling turnstile gate, similar in operation to a one-way revolving door, but with metal teeth, eliminating the possibility of re-entry. The permission only to exit and not re-enter the platform gives me hesitation. I don’t know where I am but I’m pretty confident that all I have to do is go around and find the opposite platform, and so I push through.

On the other side is a battlement overseeing the platform below, and I think to myself, must be some new extension in Sherbrooke, east past the Saint Lawrence—

But as I come up, I’m greeted with the bulge of polished metal, more nauseating amounts of grey and another hallway, like a maintenance tunnel, that funnels into a ripple of stairs up to more and more grey.

When I emerge into the next atrium, face flushed, I can hardly breathe. My pace scatters along but then stops as the foretaste of dread hits me with prodigious force. It seems at once impossible to claim that it’s only my imagination.

There is no outbound platform.

An astonishing bewilderment fills me, then patinas with frustration. What’s extra-fucking-ass is that this is cutting in on my plans. I hadn’t scheduled an excursion to concrete wonderland, and the more time that ticks by, the further in the day we get, and then rush hour, the arteries of Montreal’s subway line pulsing with life, and the fervour of it might get me to change my mind; it has before, so I’m trying to hurry it up, the way you hurry up and schedule a dentist appointment first thing in the morning—to get it over with.

I hurry down another hall, thinking, this time, for sure: the outbound platform. But no. At the end is something else entirely.

At first, I don’t see the necessity for such complex geometry. It seems to violate the laws of physics and bend the laws of nature.

It is insurmountably large, a gargantuan organ which possesses the verticality of a tower. Every bit of it seems made of concrete, that subtle wash of slate-grey, dark and sovereign. There are snapshots of other material, the cut of stainless-steel banisters, gently wafting empty escalators sweeping up three stories past the point of converging lines telescoping in on themselves before disappearing, acrylic sheets covering tiled ads for a Thai food restaurant: two bobble-headed faces with chattering marionette teeth and too-white eyes girdling an Oktoberfest special, their faces not quite right, as though processed ineffectively by some artificial mechanism. There is a row of eight STM-branded turnstiles, and an empty control kiosk emanating a jaundiced bioluminescence. The light is of a place once visited; in a dream, as a child. To me, it is wildly disorienting.

Protrusions and overhangs make it impossible to see around certain edges, hiding things in shadows, openings perhaps, doorways and crawl spaces, and as I step forward, I find myself questioning: just how much of it is accessible? How much of it is decorative?

There is stillness here, though not in the way that a church is still, or a meadow, or a shore. It is a place that has intention—an interior built for humans, wholly unoccupied by them. A place that has been here a long time. Big, with function, for people, but devoid of any life and imbuing the space with a mild perception of wrongness.

It gradually dawns on me that I’ve been denied a destination, caught in a transitional environment, a space between beginning and an end. What I see towers benedictive above my head, and is certainly not Honoré-Beaugrand terminus; I know this now.

Here stands a structure whose purpose was made for people. A space with a very clear intention. Deserted. Forgotten. It’s weird, I think. I don’t know. A space made for travelers, void of such motion, and I cannot dispose of its perverse emptiness.

I’m dwarfed by the scale of it.

Every bit of it is carved into rough, angular lines. There are no curves, save for the semi-circular handrail gently churning over the newels of the escalators at their landing thresholds. Few of the ceilings are flat. They soar up, forty, fifty feet and cut at odd facets, sometimes meeting in neat triangles, other times disseminating into geometries that make no sense.

Fluorescent lights flood from everywhere, emanating a faint buzz, but still the place seems dark as though oneiric: a disturbing cast of greenish colour-temperature diffused through protruding beams and slanted balconies, their grooved ceiling lines, as though fingers dragged through the sand, but no, there is nothing natural about this place.

Excerpted from Coup de Grâce, copyright © 2024 by Sofia Ajram