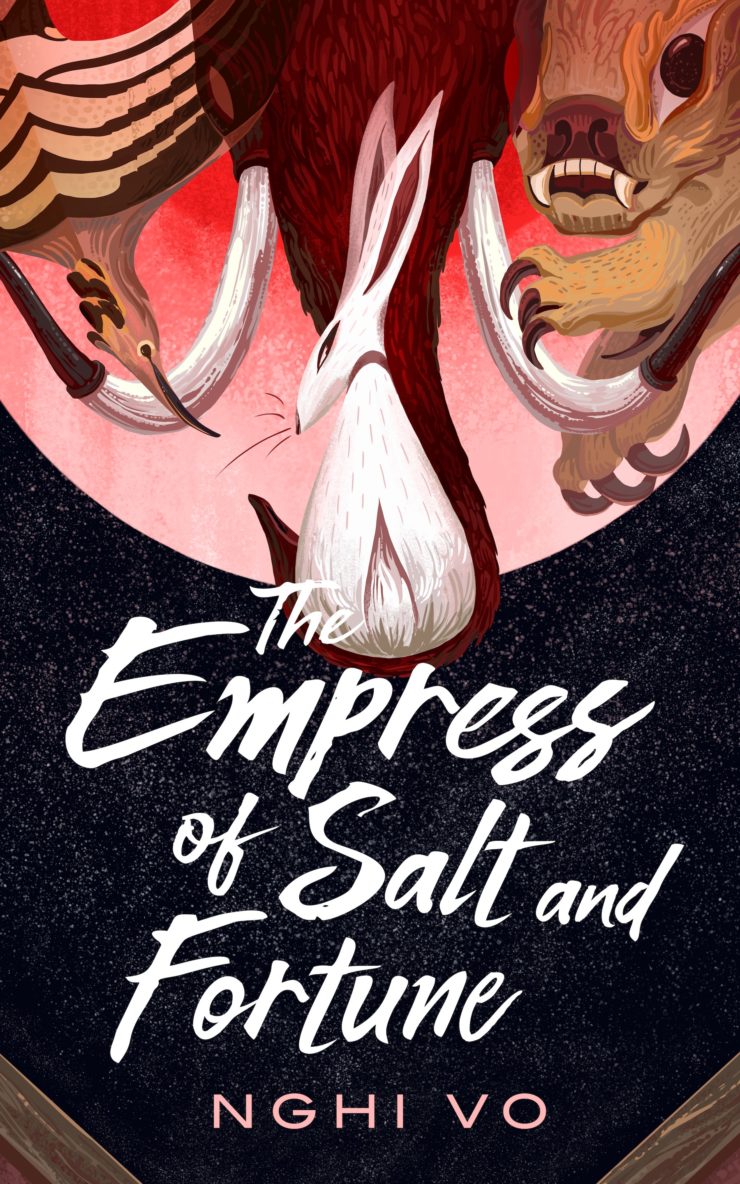

We’re thrilled to reveal the cover for The Empress of Salt and Fortune, Nghi Vo’s debut fantasy, available March 24, 2020 from Tor.com Publishing! Check out the full design by Alyssa Winans below, and join a conversation with editor Ruoxi Chen and author Nghi Vo on the age of diaspora fantasy.

With the heart of an Atwood tale and the visuals of a classic Asian period drama The Empress of Salt and Fortune is a tightly and lushly written narrative about empire, storytelling, and the anger of women.

A young royal from the far north is sent south for a political marriage in an empire reminiscent of imperial China. Alone and sometimes reviled, she has only her servants on her side. This evocative debut chronicles her rise to power through the eyes of her handmaiden, at once feminist high fantasy and an indictment of monarchy. In-yo and Rabbit fight battles both at court, full of deadly diplomacy and beautiful objects, and on the field, littered with bloody histories and armies that move on mammoth.

Buy the Book

The Empress of Salt and Fortune

Editor Ruoxi Chen and author Nghi Vo sit down to discuss working together in the age of diaspora fantasy and the rare and thrilling experience of putting together a book born out of the Asian diaspora that was written, edited, and designed by members of the Asian diaspora.

Ruoxi: As you know, Empress was one of those books I read in one gulp on a Friday and emailed everyone frantically about immediately because it destroyed my impulse control. “Realism” is always a tricky question when it comes to fantasy, but something about the details, the characters, the imagery, the feel of its world, felt unanswerably real to me, not in the way of a history book, but in the way of a true dream. Did you pull from any particular history, mythology, or era when you wrote it?

Nghi: The Empress of Salt and Fortune is a synthesis from almost getting an East Asian Languages and Culture minor in college, reading Tales from Make-Do Studio while half-asleep, and trying to fill in the gaps after watching too many kung-fu movies with my grandpa as a little kid. It’s got influences from Tang China, Heian Japan, and some of the things I’ve absorbed from my parents’ experiences in the Vietnamese diaspora as well, a certain sense of unease, defiance and displacement. Essentially, it’s a lot of weird stories and awful history blended together and then steamrollered by colonialism and dissent!

Ruoxi: This is also a book that ultimately indicts monarchy, despite the fact that the Empress In-yo is such an arresting character. In the diaspora, there’s a tendency to romanticize royal and imperial pasts as a counterweight to more recent oppression—how did you weigh that dynamic when crafting the book?

Nghi: I weighed it with a certain sense of dismay and helplessness, is how I did it! The first pole the story wraps around is how much the main character, Rabbit, loves the Empress In-yo. The second pole is how terrible In-yo is, in the old meaning of the word: awe-inspiring, grand, monstrous and more than a little deadly. In-yo’s choices are to be terrible or to be a footnote in an enemy empire’s history of a forgotten and subjugated people, and she knows which one she picks.

When you’re cut off from the culture that birthed you, you have so many unexpected choices and sometimes what feels like none at all. You get strange, you get strong, and you can get desperate. That’s In-yo. (I really liked writing In-yo, in case you can’t tell.)

Ruoxi: It feels so special to work on a book like this as an Asian-American editor working with an Asian-American writer. Empress feels specifically like a diaspora book, with its themes about assimilation and adaptation, even though it wears the (beautiful) trappings of a more traditional East Asian classical history. Did you have an audience in mind when you when you wrote it?

Nghi: The easy answers are that I wrote it for a younger version of me who read all the Lawrence Yep books in my grade school library, looked around and said “wait, is that all?” Between works from stars like Aliette de Bodard and JY Yang, the answer to that question is growing to be a louder no, and this book—and almost everything I write—is adding a little weight to that no.

The weirder answer is that the narrator Chih, my little non-binary cleric who is off to make their career in the brave new world, is written as a kind of beacon for voiceless people silenced under the weight of the history machine. Their job is to run and find out, to record and to make true, and in the end, this book was written for the story under the story, for the voices that can only rise fifty years later, or a hundred or only after a certain world is over and a new one begun. Chih’s job is lifting up those voices, and I like to think that Empress is written for those voices as well.

Ruoxi: And finally, that cover: I know it was important to both of us that someone from the Asian diaspora work on it, and Alyssa Winans has delivered so much here in its elegance, its detail, its visual flourishes. How did you feel when you first saw it?

Nghi: I yelled a lot! I was so excited when I first saw Alyssa Winan’s work, and I knew that whatever she came up with for Empress, it was going to be spectacular. Everything from the expressiveness of the rabbit to texture of the cover to the curve of the mammoth’s tusks was thrilling to see, and of course it’s my first cover, which I figure has got to be an emotional moment for any writer. It was overwhelming in the best way, and it made all of this realer than it had been a few moments before. There’s a realer-than-real quality to Alyssa’s work, and I’m so glad she’s a part of this project!