In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

This is the hundredth review in the Front Lines and Frontiers series, and I thought I would mark that occasion by finding a book I loved from my early teens, jam-packed with action and adventure, from one of my favorite authors; a story that fits the charter for this column to a T. Accordingly, I present to you one of H. Beam Piper’s classic novels, Space Viking—a tale of vengeance, plunder, rescues, space battles and derring-do.

The Front Lines and Frontiers column began four and a half years ago. Originally appearing monthly, it now appears bi-weekly. It looks at the science fiction and fantasy books I have read and enjoyed over the years, largely stories from the last century that focus on action and adventure. The heart of the column is down in my basement; I have saved nearly every book I ever read, and those hundreds of books give me lots of material to choose from. Occasionally, I’ve strayed from the standard format, reviewing newer books that harken back to the old styles, and sometimes books I missed when I was younger, like Doc Smith’s Lensman series. I look at the joys and strengths of the old books, but also try not to ignore the flaws and prejudices many of them contain. My pile of books waiting for review had been shrinking a few months ago, so I went through my boxes again, and those who enjoy the column will be pleased to hear that I have unearthed enough material to last for years to come.

I first encountered Space Viking in the pages of Analog magazine, where it was serialized between November 1962 and February 1963. I didn’t read it when it first came out, but during the late 1960s, when I was in my early teens, I found a pile of Analog magazines in our basement that were different than the others. For a short time, Analog had been published in a larger format, the size of the ‘slick’ magazines like Life. I was drawn to these issues in particular, I think, because the large format allowed the art, which was always evocative and interesting, to shine. The cover for that serialization was by John Schoenherr, and his painting of the big, spherical Space Viking ships floating down on contragravity was an image I long remembered (and years later, when I saw the Separatist Core Ships in the Star Wars: Attack of the Clones Battle of Geonosis, I wondered if that painting had influenced the scene).

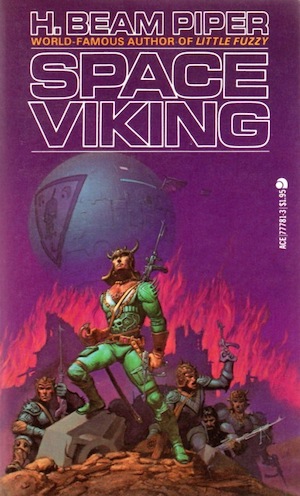

The cover for the Ace edition I reviewed, as seen above, was among the many covers painted by Michael Whelan for Ace’s Piper reissues. These colorful and evocative covers not only helped sales of the Piper books, but also helped bring this promising new artist to the attention of the science fiction community. Those Ace editions are one of the primary reasons Piper is still remembered today. Jerry Pournelle had been solicited to write a sequel to Space Viking, and asked his assistant, John Carr, to research the setting of the book (unfortunately, the Pournelle sequel never saw the light of day). John found that Piper’s Terro-Human history was far more intricate and consistent than most people realized, and one of the most detailed and sweeping future histories that any science fiction writer had ever imagined. John went on to not only organize and edit the Ace Books reissues, but also wrote a biography of Piper and continued Piper’s work (including sequels to Space Viking), with books available from his own Pequod Press (full disclosure: John is a friend of mine, and I have written stories for his War World series).

The copyright on Space Viking has lapsed, allowing other authors to explore this universe. One of them is Terry Mancour, who has also written two sequels to the novel.

About the Author

H. Beam Piper (1904-1964) was an American science fiction author whose career was cut short by suicide before his work found its greatest success. I have reviewed his work here before, including Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen, which includes biographical information, and Little Fuzzy, where in addition to more biographical information, I discussed his Terro-Human Future History, of which Space Viking is a part. You can find a great deal of additional information on Piper at the website http://www.zarthani.net/. Piper’s copyrights were not renewed after his death, and as a result, many of his works are available to read for free from Project Gutenberg, including Space Viking.

Even If You Learn from History, You May Still Be Doomed to Repeat It

In my mind, I tend to divide most science-fictional views of the future into two categories. There is the optimistic viewpoint that humanity will evolve over time, and its institutions will become stronger, longer lasting, and more effective. This viewpoint is typified by stories of utopias and transcendence, where war, conflict, and scarcity have become a thing of the past. The Federation of Star Trek is an example of a fictional portrayal of a better society (although over time, the need for dramatic situations drove writers to explore the darker corners of the Federation).

Then there is the cynical viewpoint that human nature, for better or worse, will remain essentially the same, and that its institutions and governments will continue to have finite lifetimes just as individuals have, with cycles of growth and decay. The first, optimistic viewpoint led to stories which assumed that races developing space travel would have evolved past things like conflict and warfare. Any aliens advanced enough to visit Earth would of course come in peace, and humans would live in harmonious comfort. The second, more cynical viewpoint is shown in stories of alien invasion, interstellar wars, conquest and piracy; a much messier future, but also one full of dramatic possibilities.

Buy the Book

Fugitive Telemetry

H. Beam Piper’s Terro-Human history falls into my cynical category. His stories are rooted in a broad sweep of history that sees the rise and fall of federations, democracies, monarchies, empires, alliances, and leagues. His technology, which includes contragravity and faster than light travel, allows patterns of trade, warfare, and governments that have been seen in Earth’s history to span multiple worlds. His universe, devoid of other intelligent races, permits humanity to spread from star to star, just as it spread across the Earth: Imagine the messy expansion of the United States across the continent of North America writ large across the stars.

In Space Viking, civilization on the worlds of the Old Federation has collapsed, and the old culture has given way to barbarism. The worlds have varying degrees of technological advancement, with none of them approaching the technology of the worlds that had maintained interstellar travel. Sitting on the riches of the old civilization, but without the technology to defend themselves, they are ripe for exploitation. On the Sword Worlds, advanced planets governed by a loose collection of neo-feudal monarchies, expeditions to the old worlds are financed by those seeking riches. This is a brutal practice, robbery on a planet-wide scale, where warfare is waged for profit. It mirrors the practices of the Vikings of the Middle Ages, and many of the European explorers of the 16th through 19th centuries. In this future, mankind has definitely not evolved to a more civilized form.

Space Viking

The book opens on the planet Gram, where the Baron of Traskon, Lucas Trask, is about to marry Lady Elaine, his true love. She is being stalked by Andray Dunnan, a young noble who is more than slightly mad. Lucas is planning on settling down to a quiet and peaceful life, and resents the Space Vikings, who he feels are drawing talent and resources from Gram that will make the world weaker. But then Dunnan murders Elaine on their wedding day and steals the Space Viking ship Enterprise. Trask’s thirst for revenge drives him to become a Space Viking as a way to find and destroy the man who ruined his life.

When I was young, I just accepted this scenario as written. As an older reader, I flinched as I recognized the sexist trope of “fridging” a female character, with Elaine existing in the narrative simply to die and motivate the male main character’s actions. It’s too bad, because while male characters dominated Piper’s work, he often wrote compelling female characters, like the determined archaeologist from his classic story “Omnilingual.” I also recognized the influence of Raphael Sabatini, whose tales of piratical revenge, like Captain Blood and The Sea Hawk are clear precursors to this story. [The resemblance was so strong that I recently confirmed with John Carr that Piper was a fan of Sabatini. He replied that the author had frequently mentioned Sabatini’s work in his diary.] Trask trades his barony for a ship he christens Nemesis and brings aboard experienced Space Viking Otto Harkaman to aid him in his search.

One of the things that keeps this tale from being too dark is that Trask is essentially a decent and civilized man. While he thirsts for revenge, and takes on a bloody profession, we also see him constantly looking to minimize casualties, to trade instead of plunder, and to build a new and better society through his actions.

Trask takes his ship to the planet Tanith, where his world had planned to establish a forward base. He finds other Space Viking ships there and takes them on as partners. His crew plunders a number of planets, and he finds opportunities for those worlds to establish mutually beneficial trade with each other (as befitting those civilized instincts I mentioned above). These raids, and the battles that ensued, fascinated me when I was a youngster, but as an old-timer, I just kept thinking about the death and collateral damage, and the inhumanity of causing all that destruction simply to make a profit.

Trask also rescues the starship Victrix and makes common cause with the rulers of the planet Marduk, who have been clashing with the evil Dunnan’s allies. Their world is a constitutional monarchy, plagued by a charismatic con man who undermines and eventually overthrows their democratic institutions, then the monarchy as well (a narrative I now realize is very closely modeled on the rise of Adolf Hitler). Trask learns there is a civil war on his home planet, but he no longer has any interest in returning. His new life absorbs his efforts, and he has developed feelings for a woman from the Mardukian court. Unlike 20th-century Germany, Marduk is saved by Trask’s intervention; he unseats the usurper, who turns out to be allied with Trask’s archenemy Dunnan.

Trask’s solution to the planet’s problem, in addition to providing military muscle, is to suggest the king worry less about democracy, and more about what he feels needs to be done. Trask himself declares independence from his home planet and takes over as a king on Tanith. When I was a younger reader, this seemed like a great idea, as giving the good guys more power looked like an ideal solution. From my more mature viewpoint, I know that wise and benevolent despots are a pipe dream, and would have preferred to see a restoration and strengthening of democratic institutions as a solution to their problems.

In the end, readers will not be surprised that Trask finally encounters Dunnan, accomplishes his revenge, and then finds peace and happiness—a rather neat ending to a bloody tale. A good ending for a young reader, but somewhat overly simplistic and unsatisfying to my older self.

The book was a quick and enjoyable read, despite feeling more flawed than it did when I first encountered it. Piper was a skilled author, evoking new societies and worlds with a minimum of exposition, and describing combat in a manner that was both clear and exciting (modern writers could benefit from emulating his straightforward and economical prose). The characters were sometimes a bit thin and predictable, but they hit their marks, and Trask was a compelling and sympathetic lead. Even though I was horrified by the ethics of the Space Vikings, and found their political solutions repugnant, Piper was a strong advocate for his ideas, and his political observations were enlivened by lots of action.

Final Thoughts

Space Viking is an enjoyable and action-packed book, although a bit too simplistic to satisfy the more jaded reader I have become in my old age. That being said, it is one modern readers could still enjoy (and, as mentioned above, you can read it for free via Project Gutenberg).

I do want to pause and thank everyone who has commented on my reviews over the years… Getting your feedback and interacting with you is one of the best parts of the job. And now it’s again time for you to chime in: If you’ve read Space Viking, or other works by Piper, I’m interested in hearing your observations. And I’d also be interested to hear your thoughts, as science fiction fans, on what versions of the future you prefer to read about… Are you fascinated by the more cynical stories of futures where societies rise and fall, and raids from predatory pirates and Space Vikings might be possible? Or do you prefer stories in which optimism ultimately wins out over cynicism?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.