I’ve often heard Climbers described as the least fantastical of M. John Harrison’s novels, and so it is, looked at in a particularly literal light—I espied no spaceships, I’m afraid, and there isn’t a single sentient bomb in sight—yet this reading is as wrong as it is right.

Climbers is certainly less overtly otherworldly than the Kefahuchi Tract trilogy, and it has none of The Centauri Device’s spare spacefaring. Indeed, it takes place almost entirely in the north of England in the eighties, but do not be so easily deceived: Climbers is far from absent alien environs.

The Andean landscapes […] had a curious central equivocality: black ignimbrite plains above Ollague like spill from some vast recently abandoned mine: the refurbished pre-Inca irrigation canals near Machu Picchu, indistinguishable from mountain streams. Half-seen outlines, half-glimpsed possibilities; and to set against them, a desperate clarity of the air.

This is the work of a bona fide stylist, reminiscent of recent Christopher Priest, or China Mieville at his most memorable, and even here in his most mainstream text to date Harrison imbues his landscapes—though they are real rather than imagined—with such bizarre and startling qualities that you’d be forgiven for thinking Climbers is science fiction.

At bottom, it’s about a man—readers, meet Mike—who leaves his life in London behind after the failure of his first marriage. Disillusioned and disconnected, he moves to the Yorkshire moors, falls in with a clique of climbers, and slowly but surely insinuates himself in their increasingly extreme endeavours.

To climbers, climbing was less a sport than an obsession. It was a metaphor by which they hoped to demonstrate something to themselves. And if this something was only the scale of their emotional or social isolation, they needed—I believed then—nothing else. A growing familiarity with their language, which I had picked up by listening to them as they practised on the indoor wall in Holloway, and their litter, spread out on a Saturday afternoon like a glittering picnic in the deep soft sand at the foot of Harrison’s Rocks, had already made me seem quite different to myself.

In climbing, Mike finds a way… not to escape, exactly, but to be a part of something greater. Something purer, or at least less muddy than the life he’s lost. His pursuit of the present, of mastery over the moment—by way of puzzles and problems solved on chalky rock walls—is, I think, a fundamentally powerful thing, and in time it takes precedence over every other aspect of his existence.

He does, however, have cause to recall what brought him to this point: namely the end of something hardly begun—a death, yes—which we only ever glimpse in shattered fragments, reflected in shards of mirrored glass. It falls to us to put the pieces of Mike’s memories together, and I dare say your willingness do this—to work towards a passing grasp of character and narrative that the author obfuscates at every stage—will determine what you ultimately take from this tale.

The story, such as it is, does not unfold chronologically. Though Climbers’ structure implies a year in the life, from Winter through Spring to Summer followed by Fall, and there is a linear element—a single thread that wends its bewildering way through the text in toto—in truth Harrison’s 1989 novel is more memoirish, replete with recollections and ramblings such that we only learn about Mike’s separation from his wife and the circumstances of said perhaps halfway through the whole.

To be sure, Climbers can seem inscrutable, but to a greater or lesser extent this is true of Harrison’s entire oeuvre. As the similarly inclined nature writer Robert Macfarlane asserts in his insightful introduction to the new British edition:

“Harrison’s [books] explore confusion without dispelling it, have no ambitions to clarification, and are characterised in their telling by arrhythmia and imbalance. Nothing in Climbers seems quite to signify in the way it ought to, events that should be crucial flit past in a few sentences, barely registered. The many deaths and injuries that occur are particularly shocking for the distracted scarcity of their narration.”

And so to the characters Mike meets: to Normal and Bob Almanac, Mick and Gaz and Sankey; isolated individuals who become comrades in climbing whilst flitting in and out of the fiction whenever real life intervenes. They come and go, and they’re hard folks to know… but people aren’t easy. We are complicated, contradictory creatures, and Mike’s new mates struck me as more human than most. As right and as wrong as us all.

Its parts are undeniably abstracted, and there will be those who take issue with this, understandably perhaps, but cumulatively, Climbers is as complete and pristine as any of the SF classics Harrison has composed. Nor is it any less revelatory. Indeed, some say it is his piece de resistance. I don’t know that I’d agree with that assessment—however mesmeric the landscapes, however impeccably crafted the narrative and characters are, I don’t know that Climbers has the scope or the outlandish imagination of Light and the like—nevertheless, Harrison imbues the ordinary of this novel with such extraordinary qualities that it is not, after all, so dissimilar in effect to the best speculative fiction this remarkable author has written.

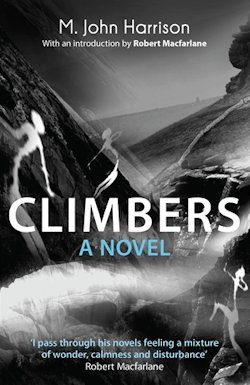

Climbers is published in the UK by Gollancz. It comes out May 9.

Niall Alexander is an erstwhile English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com, where he contributes a weekly column concerned with news and new releases in the UK called the British Genre Fiction Focus, and co-curates the Short Fiction Spotlight. On rare occasion he’s been seen to tweet, twoo.