Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

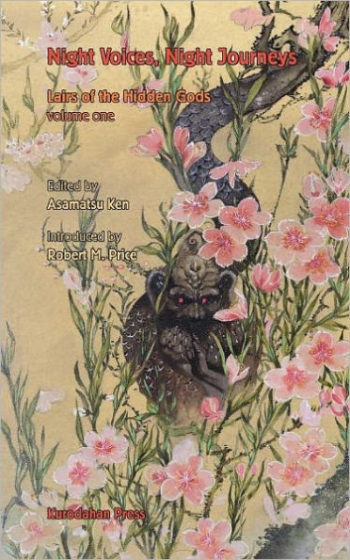

This week, we’re reading Shibata Yoshiki’s “Love for Who Speaks,” translated into English by Stephen A. Carter. This version is first published in Asamatsu Ken’s 2002 Night Voices, Night Journeys anthology; we haven’t been able to find publication information for the original Japanese version. Spoilers ahead.

Make dark supplications to the new moon, big supplications to the full moon, and supplications small and secret to the crescent moon.

Summary

Chisa’s father left when she was an infant, but she retains fragmentary memories of his voice and touch. Her mother remarried; the new family of three was happy. Yet Chisa from early childhood has offered prayers to the crescent moon, which oversees supplications “small and secret”: Please, let her see her father again.

Through a relative, adult Chisa meets Izutsu Masaaki. She has dated before, but the search for connection has “always felt like it was happening to someone else.” The “other party” has always broken off their relationship, claiming he doesn’t feel she really loves him, or is even trying to. Masaaki’s different. With him it will be an arranged marriage, and after all, marriage and love are two different things.

Buy the Book

Flyaway

Chisa and Masaaki date. She finds him compatible enough, fun, and he’s financially secure. The one thing that makes her uneasy is his reluctance to take her to see the ocean—he diverts their outings inland instead. That shouldn’t be a problem, given Chisa has no longstanding love for the sea. In fact, as a child, she experienced so great a terror “that [the waves] would drag her down, to a place deep down at the bottom of the sea,” that she screamed and wept. Since then, she’s been content landbound. Since then, until now.

Chisa and Masaaki become engaged. On their last date pre-wedding, she asks him again to take her to the ocean. Chisa insists; he yields. They drive to Izu and gaze out over the water. The salt-spray calms Chisa’s heart. She envisions a silver man, “supple and powerful as a dolphin” as he swims beneath the waves. Without speaking, she asks who he is. He laughs. It doesn’t matter. Just come into the water. He likes her, he loves her. So come to him.

Impatient, face pale, Masaaki calls her back to reality. He doesn’t like the sea, the smell, the waves. It’s all right, Chisa says. She’s seen enough.

They marry, and it’s a good life. Masaaki never tells Chisa he loves her, but that’s all right. She’s a woman peeking from a shell at others. He’s a man who does the same, so they suit each other. Besides, in the ocean a man loves and waits for her. On crescent-moon nights, when Masaaki’s presence keeps her from supplication, she lies awake thinking of the silver man.

One morning, a woman named Takagi Emi appears at Chisa’s apartment, claiming Masaaki was previously engaged to her missing sister Sawako. Emi believes Masaaki may have murdered Sawako following their trip to Izu. Why? Emi thinks Sawako found out about Masaaki’s pre-Sawako fiancée, who also disappeared, and so Sawako broke off their engagement. Any case, Chisa better beware. If Masaaki suspects his wife knows his secrets, he may kill her too!

Chisa calls Masaaki’s college friend Masahiko. Masahiko admits that Masaaki’s first fiancée, Shioda Keiko, did go missing. Yes, Emi’s pestered him, too. Emi’s deluded. See, Keiko’s family knows she disappeared while traveling alone—their last contact with her was a postcard from Izu, from Yumegahama Beach to be exact.

Which is exactly where Masaaki took Sawako, according to Emi. Which is exactly where Masaaki took Chisa… Chisa returns alone to a wintery Yumegahama Beach. A silver hand emerges from the waves. The silver man has been waiting long, and begs her to join him. She was born in the sea; she’ll be able to swim. As for those she seeks, they’re already underwater, and happy to be there. Chisa puts her feet in the surf, but the cold drives her back, screaming.

That night Masaaki smells the sea in her hair. He shouts, then sobs that he doesn’t want to lose her to the ocean. He lost Sawako and Keiko to it, but no, he didn’t kill them. Chisa promises she’ll stay with him. She doesn’t want to give up her “calm, quiet, shell-enclosed life.”

Morning, however, finds her ankle-chained to the bed. Masaaki’s taking extreme measures to prevent her disappearance. Days while he works, he locks her in their apartment. Nights he chains her. Evenings he’s willing to walk out with her, but only with her shackle-leashed. Chisa prefers imprisonment to that disgrace and languishes uncounted days. A crescent-moon night comes; despite Masaaki sleeping beside her, Chisa supplicates the moon to send her true father. A black shadow appears and calls her his daughter, then proclaims that she’s bound to return to the Great Old Ones’ sea-bottom city to marry and gain new life. Masaaki, the fool, is a minion sent to bring their daughters home. Masaaki furiously claims Chisa belongs to him, but Father gathers her up, melting her shackle, carrying her through the sky to the sea, into which he gently drops her. There’s a brief agony before she breathes water and swims with fishlike ease. Scores of swimmers accompany her. Their eyes are lidless, their mouths lipless, and gills gape in their necks. Their scales gleam silver. Without fear, Chisa accepts she’ll become like them. A new world awaits her below, the glory of forgotten days, the joy of an inevitable revival!

In the glittering sea-bottom city, Chisa meets Sawako and Keiko, transformed. Her silver lover tells her the daughters of the Great Old Ones are being gathered. Soon their people’s time will come again.

Chisa sees Masaaki once more, while swimming with her silvery newborn. He’s taken the form of a giant, ugly moray eel; he shrinks from her gaze, but not before she reads in his “painfully beseeching” eyes that he loved her.

If only he’d said that before, Chisa tells the retreating eel, just once, in a whisper—before he put on the chains.

What’s Cyclopean: The most cyclopean adjective this week is a “grotesque eel”; most of the language is as deceptively straightforward as the edge of the sea.

The Degenerate Dutch: No judgments between humans, but the Great Old Ones leave somewhat vague what will happen to the humans once the “revival” comes.

Mythos Making: The Great Old Ones depend on minions to return their daughters to the sea. The minions are not always dependable.

Libronomicon: No books this week.

Madness Takes Its Toll: No madness this week, unless very bad relationship skills count.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

If you want a good relationship, communication is key. You should tell your partner about your experiences, your work, your past relationships. If you’re prone to feelings, you should mention those too. And definitely, no matter what, you should talk about your problems and potential obstacles to a happy life together. Obstacles, let’s say, like being under an oath to deliver your wife to ancient under-sea entities. There are a lot of solutions to this sort of common problem, and the ones that involve talking to your wife rather than chaining her to the bed are much less likely to result in being transformed into a giant eel.

Any plan where you get turned into a giant eel is a bad plan. (People making deals with either Great Old Ones or Ursula the Sea Witch, take note.)

This is a weirdly low-key story, for a tale in which a woman gets imprisoned by her husband and then escapes to dwell in wonder and glory and apocalyptic anticipation among the Deep Ones. So much mythosian fiction is a roller-coaster of emotional intensity—passion, terror, irresistible temptation. “Love for Who Speaks” is mostly about a woman being deliberately okay with a life that’s… fine. That’s comfortable and contented and entirely unthreatening. It’s almost more claustrophobic before she’s shackled to the bed and realizes that her fine life really isn’t fine at all.

Yet, beneath this façade of non-intensity, Chisa is much like the narrator of “Shadow Over Innsmouth.” She’s drawn to the sea and fears it in equal measure—it’s just that she’s been raised to push her desires far below the surface, and make sure no one ever notices that they exist. She tells the moon, but only when no one else can hear—until at last she risks her captor/husband learning her desires, and prays in front of him. This, apparently, is what her father has been waiting for. And then, only then, she’s permitted words like “glory” and “joy.” And, if not “love,” then at least liking a lot. There’s a lot of passion down there, beneath the surface.

Maybe a better comparison than “Shadow” is the narrator of “The Yellow Wallpaper,” imprisoned by those who supposedly love her, desperate to break out in any direction available. Chisa, at least, has a better escape route.

Masaaki is constrained in some of the same ways. He can’t reveal his truths, either the remarkable ones or the more mundane ones like “I love my wife.” Since he never gets over these constraints (and also gets turned into an eel), he remains an enigma. Why does he date the women he’s supposed to return to the sea? He seems to figure out pretty quickly who’s actually a Daughter, so it’s not like he has to get to know them. He could bring them to the ocean on a first date, and they’d probably disappear before their families knew him well enough to be suspicious. He could have explained the whole business to Chisa—yes, emotional conversations are hard, but I regret to point out that once the shackles appear, you’re pretty much admitting to having them.

I’m going with “raised as a cultist, secretly wants a normal life, has absolutely no idea what that looks like.” And thinks, possibly from experience, that shackling someone to the bed is a regrettable but basically reasonable way of handling conflict. Um. I don’t have that much sympathy, but are there any therapists who work with eels?

Anne’s Commentary

In his Night Voices, Night Journeys biography, Shibata Yoshiki notes that “The Dunwich Horror” was his introduction to Lovecraft, but that “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” is his favorite Mythos story. No wonder, then, that he’s written so affectionate and lyrical a take on the Deep Ones. “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” he continues, initially impressed him with its “portrayals of nature and the psychology of the traveler [narrator],” which struck him as “beautiful and almost illusionary.” For him, Lovecraft’s measured opening and exposition “make the plunge into horror in the second half that much more effective, more concentrated.”

I agree and add that the openings of “Dunwich Horror” and “Color Out of Space” have a similar effect on what follows. Shibata chooses to stress beauty and illusion over horror, giving “Love for Who Speaks” the fantastic tone of fable or fairy tale in spite of its contemporary urban setting. This isn’t to imply the story’s not unsettling—look at how thickly shadows pool in the stories of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen, as their monsters mirror human nature and their humans the nature of monsters. I’m never afraid of the silvery man and his kin, whereas the apparently “normal” (or even supernormal) Masaaki had me on edge early on—and proved my potential-abuser radar in working order when he took actual possession of Chisa with locks and chains and leashes, disabled phones and curtains that blocked out her share of the sun.

You just knew that marriage was not going to work out in the end. Chisa thinks she’s being practical to separate marriage and love; she’s laudably self-aware to characterize herself as a creature peeking out of its shell instead of daring an unarmored approach to the world. She’s no heroic romantic, okay, but she’s comfortable and quiet and safe. Nothing wrong with that, so long as the snail accepts it’s a snail, not a—fish? Not an ichthyoid, let’s say. Not a Deep One.

The trouble is, if you are a Deep One, you can only hide it for so long. Genotype will win out; the juvenile human phenotype will give way to the mature amphibious, and the more complete the change the better. To be stuck between morphologies would leave one crippled in both the airy and the aqueous worlds. Seanan McGuire explored that horror in “Down, Deep Down, Below the Waves.” Go back to the original, Lovecraft’s “Shadow”—he drops dark hints about Innmouth-Lookers who don’t transform enough to revel in Y’ha-nthlei, cradled in the scaly bosoms of Father Dagon and Mother Hydra. Or who are kept from transforming that far, which would have been the fate of the narrator’s asylum-confined cousin if narrator hadn’t broken him out. A Deep One must be baptized in seawater to be fully reborn.

Though the Merciful Cthulhu broadcasts dreams to call His children home, the dreams of undersea glory and communion don’t always suffice. Dreamers can misinterpret them. They can discount or reject them. Chisa’s a good example of a Deep One who struggles to ignore the Call. Inertia’s her game until inertia becomes too inert (imprisonment, in fact), and fear less compelling than longing.

Sometimes the true faith needs missionaries, the army needs recruiters, the plain old lost need finders. McGuire’s Violet Carver is a real crusader—through the miracles of biochemistry, she hopes to bring the more genetically dilute of Dagon’s children home to the sea, as well as to speed the transitions of the “slow changers.” In Ruthanna’s Deep Roots, Aphra Marsh tackles the problem of finding Deep One relations who don’t know their heritage—can Innsmouth be peopled again? Chisa has to find herself because her shepherd is false. We learn Masaaki’s a minion of the Great Old Ones, whose duty is to attach himself to Deep One daughters and, when he senses the sea begins to draw them, to get them to the appropriate beach. One assumes he’s human until he appears to the transformed Chisa as a moray eel. Is he a shapeshifter of sorts? Or is her sighting of him a vision, the eel-form a metaphor for her treacherous husband? [RE: I interpreted the eel-form as a punishment imposed from outside, but admit it’s pretty ambiguous.]

While condemning Masaaki for his treatment of Chisa, I also feel sorry for him. Being a Great Old One minion seems like a drag. Shadow-Dads yell at you. You’re always the suitor, never the groom. And then, what if you fall in love with one of your charges? What if the idea of losing her to the sea grows unbearable?

Masaaki, Masaaki. You should have glanced up at the title of your story. “Love for Who Speaks,” get it? You should have poked far enough out of your shell to tell Chisa you loved her. You wouldn’t have had to emulate the unabashed declarations of Silver Man. A whisper would have sufficed.

And then couldn’t the fairy tale ending have been the marriage of eel and Deep One? I mean, they both have fins, and I think morays are quite handsome myself, if a tad toothy. Then again, Silver Man is all dolphiny (in looks and attitude), and don’t those damn dolphins always win the oceanic popularity contest?

Next week, we continue to explore relationship issues in Caitlin Kiernan’s “Love is Forbidden, We Croak and Howl.” You can find it in the Lovecraft’s Monsters anthology.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.