There’s a weird internal nostalgia in this entry in the Norton canon. It’s both a Ruritanian romance and a Gothic romance. On the one hand it harks all the way back to Norton’s first published novel, The Prince Commands. On the other, it was published during her Gothic period, in 1980, and there are echoes of the Witch World that almost made me think she was hinting very vaguely at one her other favorite themes, parallel worlds.

The result is a strange, dark, not quite coherent novel.

Obligatory orphaned heroine Amelia receives a deathbed bequest/command from her grandmother, to bring closure to an old family scandal. Her grandmother had married a European aristocrat, heir to one of those multitudinous Germanic principalities, who fought in the American Revolution as a Hessian mercenary. He produced a son and then was called back home to take his inheritance, where he was forced to repudiate his American wife and submit to an appropriately aristocratic marriage.

By American law, the first marriage was and remained legitimate, as did its issue, including, ultimately, Amelia. By the law of Hesse-Dohna and the even more rigid unwritten law of upper-class Maryland, the marriage was not legal and the son and his daughter were therefore illegitimate. Grandmother Lydia has reason to believe that her husband, who is still alive, wants to right the old wrong and legitimize both the marriage and his descendants.

It is her dying wish that Amelia receive Elector Joachim’s messenger and travel with him to Hesse-Dohna to obtain the necessary affidavit. Amelia has no desire to do so and no need for any inheritance that might be forthcoming. Her grandmother has left her very well off. But she made a promise, and she intends to keep it. Amelia, like many Norton protagonists, may not be particularly strong or skilled, but she is stubborn and possessed of unshakable integrity.

There is of course a Gothic Hero, because the genre requires it. This version is an English Colonel whose family has served the Harrach Electors for generations. We know he’s the Hero because of the clear and inevitable signals: He’s not handsome but he has arresting features and personality, he’s strong and domineering and the heroine at first does not like him at all, but she can’t stop thinking—or more accurately obsessing—about him. Of course we know where that will lead.

The villains of the piece are pretty much standard issue. Amelia is entrusted to a countess who signals, in Norton Gothic, nasty plotting female: she’s plump, blonde, and much given to curls and frills and overwrought fashion. Grafin Luise is apparently besotted with the male villain, Baron von Werthern, signaled as such by his being overweight, boorish, and not nearly as pretty as his official portrait. There’s also a more remote and villainous presence: the Elector’s legitimate daughter, Abbess Adelaide. Mostly we see her from afar, stomping heavily in and out and barking out commands and threats in a rasping voice.

Amelia is dragged from one unpleasant locale to another, finally ending up in the grim prison of Wallenstein. She’s all alone without allies, though her grandfather does affirm on his deathbed that he has legitimized her and his first marriage, and she manages to secure the help of the maid assigned to her, the initially subservient but ultimately strong and resourceful Truda. There are kidnappings, druggings, a forced marriage, and incarceration in one hideous room after another, culminating in an actual prison cell.

Buy the Book

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue

And that’s when it gets strange. Wallenstein has a ghost—as such places must, in Gothic romance—but it’s not at all what it seems to be. The seeming spirit is a living child, the mentally ill daughter of the garrison commander.

Her name is Lisolette, which seems to be Norton’s inversion of the German Liselotte (Norton often got names wrong in odd ways), and she flits around the castle/prison impersonating its most celebrated inmate, the late Princess Ludovika. She has intimate knowledge of all the castle’s network of secret passages, and she drafts Amelia into her fantasy. In the process, Amelia discovers that the Colonel, who had disappeared at the Elector’s death, is imprisoned in a cell near hers. She frees him, and he arranges their escape while she distracts Lisolette.

This very nearly backfires when Lisolette drags Amelia far down into the depths of the mountain on which the castle is built (Norton must have her subterranean adventure). Amelia had thought that Lisolette’s obsession with someone someone she calls Her refers to Ludovika, but in fact it’s something much, much, much older and infinitely worse. It’s a horror straight out of a Witch World novel, an obscenely female statue inhabited by a malign intelligence, complete with Norton’s favorite horror-signal: a head like a blank ball with empty hollows for eyes.

Amelia escapes with the Colonel’s help, and there is one of several headlong rides through the horrid forest, with not-quite-chance encounter with Truda and her stalwart swain, Kristophe. Naturally they run into the Baron’s men, who are hunting them, but equally naturally, they manage to escape—assisted by one of the Colonel’s connections in a neighboring principality. And so they all return to safety and sanity in the United States, and Amelia of course, because this is a romance, has found her true love.

In a lot of ways as I read, I felt that Norton was straining against the bonds of the Gothic genre. Mashing it up with Ruritania is kind of fun, but throwing in ancient horror a la the Witch World kicks it down a fair notch.

Hesse-Dohna is an awful place in general. It’s been worked over relentlessly by centuries of war. Much of it is in ruins, and where it’s been modernized, it’s been renovated badly, with all the excesses of Victorian overdecoration, though the actual timeframe has to be pre-Victoria. Norton really, seriously did not like red velvet or heavy furniture.

The medieval underpinnings are if anything worse. Walls and parapets crawl with hideous monstrous images and carvings. Streets are dark and filthy. Rural landscapes are gutted and tormented. Amelia’s only wish is to get the hell out, even before she becomes a pawn in the various plots to gain control after her grandfather dies.

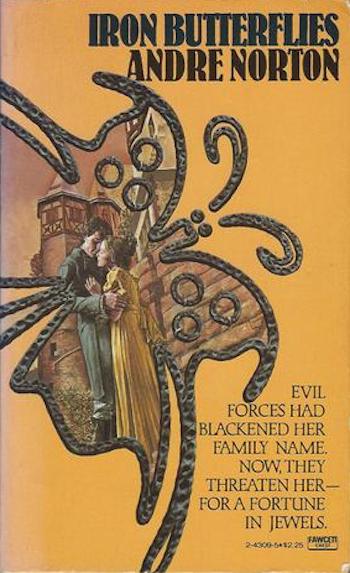

As for the title, this refers to a necklace left to Amelia by her grandmother, made of iron as a symbol of sacrifice during one of Hesse-Dohne’s endless wars. Sometimes it’s a badge of honor, other times it’s a ghastly burden that Amelia cannot stand to touch. It never really amounts to much, and it literally gets dumped in the end.

Rather like Lisolette, whose plot is distinctly problematical. Amelia has a horror of mental illness. She uses the child ruthlessly and after using her, abandons her to her horrid worship and her ghastly goddess.

Amelia makes feeble efforts toward saving her, but the Colonel talks her out of it. She’ll be all right, he says. She knows the secret passages. She’s safe. She’ll be fine.

And Amelia gives in. Maybe the girl is physically safe, but she is “broken-minded” as Amelia says. Amelia can’t face that. So off she goes with her hunky Colonel, and never looks back.

Norton isn’t generally so callous about disability, but she seems to have had more trouble with mental disability than the physical kind. It could not have helped that she lacked the skills to write nuanced or complex characters. Lisolette strained those skills to the breaking point.

I should add, in the interest of fairness, that Norton did pleasantly surprise me in a couple of places. One is the dying Elector’s description of the love he had for his Lydia. It was a true meeting of minds, a match between equals. He loved her with all his heart, but his duty to his country overwhelmed that love. And so he left his wife and family and doomed them to decades of scandal. But in the end he did what he could to redeem it.

And then there’s Amelia’s claustrophobia. For once I could relate to a Norton character having subterranean adventures. Amelia hates dark, closed spaces. For her, the secret passages and the deep dungeons are a true nightmare. Yes, I said as I read. Finally. Norton did get it about people like me.

Next time I’ll tackle Wheel of Stars. It looks like another odd one, but I’m game to try it.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Since then she’s written novels and shorter works of historical fiction and historical fantasy and epic fantasy and space opera and contemporary fantasy, many of which have been reborn as ebooks. She has even written a primer for writers: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.