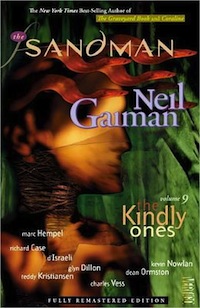

The collected edition of The Kindly Ones begins with a short story written by Neil Gaiman and drawn by Kevin Nowlan, and I think that’s a mistake. The story was originally published in Vertigo Jam #1, and I’m sure the story fits between World’s End and The Kindly Ones, and was published around that time, and all of that is just fine, but it’s not the best way to start reading “The Kindly Ones” as a story arc.

Gaiman and Nowlan are great, sure, and it’s a nice little story about a dreamer.

But as a massive thirteen-part opus, “The Kindly Ones” deserves, in a collection with its name in the title, to get the spotlight from the first page.

The first page of “The Castle,” by Gaiman and Nowlan, begins with a panel of faceless, fanged women approaching the reader, while the caption says, “There’s a dream in which huge faceless women with wolves astride them are chewing at my entrails and legs. They have sharp teeth.” There are wolves depicted in that opening panel as well.

The first page of “The Kindly Ones,” by Gaiman and Marc Hempel, begins with a close-up on a ball of gray yarn, held by a young woman dressed in black, her hands holding the ball of yarn in front of her chest. “Is it ready yet? Are you done?” says a voice off panel.

“Nearly. There we go,” she replies, and we realize the young woman isn’t merely holding the ball of yarn, but finishing the act of rolling the yarn into a ball.

The Gaiman/Hempel panel is a much more appropriate way to begin The Kindly Ones collected edition that the Gaiman/Nowlan panel, even if the latter is part of a story subtitled “(prologue).”

Gaiman and Hempel give us foreboding and yet a sense of eerie calm. The impatient voice off panel, “Is it ready yet? Are you done?” could well echo the voice of the reader, during Sandman’s initial serialization or today. In the 1990s, as the series was coming to a close, the last dozen or so issues weren’t released as swiftly as the first few years of Sandman. There was anticipation about what would happen and how Dream would meet his demise. Today, readers staring at the pile of trade paperback collections or, better yet, the four-volume massive hardcover Absolute editions would be approaching the final book(s) in the series wondering how Gaiman will tie everything up.

And that ball of yarn? Don’t we sometimes call stories “yarns”? And do writers not knit together scenes and characters to make the story come together. That’s what it’s all about.

That Gaiman/Nowlan description and image of feral women is nightmarish, and will ultimately parallel what leads to Dream’s death, but it’s unsubtle. Without the dignity the series deserves. Too on-the-nose.

No, the Gaiman/Hempel opening panel is a better one. More suited to what has come before and what is yet to come. It’s a reckoning, but not one clothed in ferocity from the beginning.

There’s also the fact that Marc Hempel’s art—blocky and angular and graphically bold and unlike anything else in the series—defines The Kindly Ones, even if he doesn’t draw every single page. Other artists who come in take their lead from Hempel on this penultimate story arc. It’s a shame to open the collection and not immediately see his images first. It’s the best pure art of his career, and it’s the best-looking Sandman arc of them all.

Oddly, Hempel’s art isn’t often associated with Sandman. When I think back on the series, I never picture Hempel’s version of the characters. I picture Mike Dringenberg’s. Or Kelley Jones’s. Or Jill Thompson’s. Or that statue based on P. Craig Russell’s version. In all those incarnations Dream is delicate, with deep-set eyes, and a look of haughty sullenness. Hempel’s Morpheus shares those traits, but he’s more a collection of shapes and lines than a fully-formed figure. He’s a drawing of a character first, and a persona second. That’s probably what I love most about Hempel’s take on Sandman’s world—that it’s so unabashedly stylized, but not at the expense of storytelling. If anything, Hempel draws everything with such bold symbolism—with him, on Sandman, it’s the clarity of image first and the movement of characters through space second—that the story becomes more quintessentially dreamlike.

Most artists would depict “dreamlike” in hazy incorporeality or crazy surrealism. Hempel depicts it as silhouettes framed against jagged backgrounds, or as angular close-ups cutting away to insert shots of important objects. His panel-to-panel rhythms are unconventional, his figures cropped oddly in the frame, and it works wonderfully to capture the conversations and the conflicts in The Kindly Ones.

If only he drew every page of The Kindly Ones, it might rank as one of the all-time great graphic novels, apart from its importance in Sandman proper. But he didn’t. It’s still really good, though.

Rereading The Kindly Ones this time, I was fascinated by the confidence it seemed to have as a story. So many other Sandman arc are exploratory, playful, and we can feel Gaiman learning new things about storytelling as he tries to layer in all the things he’s loved about stories in the past. Even World’s End felt like Gaiman getting something out of his system, as masterful as that collection was. With The Kindly Ones, Gaiman—and Hempel, and others—seemed less interested in exploring various avenues of story and more interested in telling this one, specific story. The story about Dream facing the consequences of his previous actions. The story about Dream’s past coming back to kill him.

Sure, there are digressions, because it’s a Sandman story written by Neil Gaiman, but even the digressions seem more like pieces of clockwork machinery than colorful asides. To put it another way, and bringing Neil Gaiman’s mentor Alan Moore into the equation: The Kindly Ones is to the early years of Sandman as Watchmen is to The Saga of the Swamp Thing. As a reader, I love all of that stuff. But clearly the later work is more precise (and yet still vibrant) than the former.

I might even recommend that readers who want to try out Sandman but are put off by the earlier artistic inconsistencies and the Gothic decor of the first few arcs skip all that stuff and just read The Kindly Ones. Except, I’m not sure that would work. The Kindly Ones is a carefully-crafted, immensely powerful story of revenge and resignation, but it’s also hugely dependent on the characters and situations that have appeared in previous issues. The Kindly Ones is a near-masterpiece, but it isn’t one that can stand on its own.

The good news is that readers of the entire Sandman saga have The Kindly Ones to look forward to. It’s basically the final chapter of the entire series, with The Wake as an epilogue. And what an excellent final chapter it is.

As always, it’s better that you read the story yourself and look at all the pretty pictures than have me summarize it for you, but I will highlight a couple of my favorite parts of this quite-significant and, I think, as much as Sandman is acclaimed overall, quite-underrated story arc.

Everything with Nuala, the faerie who has been left in Dream’s kingdom, is masterfully done. Nuala, who first appeared in Season of Mists, has mostly been a background character. She lives in Dream’s palace, and helps clean up to keep herself occupied, but without her fay glamour, she’s just an unkempt runt of a girl. Her brother comes to retrieve her in The Kindly Ones, and Dream grants her leave, but offers her a pendant that she can use to receive a single boon, whenever she needs him.

Gaiman piles the narrative weight of the entire story onto that one pendant-granting scene. Without ever saying why or how—though the intervening issues have showed us—Gaiman implies that Dream has profoundly changed since the beginning of his journey in issue #1. Yet, couldn’t he be granting her the boon just to remind her of his power? As an act of intimidating grace? Perhaps. But why else would he give her the pendant which grants her such a powerful boon? Is it because he has come to like her? Or because he still feels guilty about how he has treated women he has cared about in the past? Probably, and probably. But it’s all unspoken. And there’s yet another reason he has to give her the pendant and the boon: in answering her call—when it comes—he will be forced to leave his realm and fall prey to the forces who want to destroy him. He must grant her the boon, because his demise is already written in Destiny’s book.

All of that is bundled up in that one scene between Dream and Nuala and none of it is spoken about and yet it is conveyed in Marc Hempel’s wonderfully expressive character work and in the context of the scene within Sandman as a whole.

Then there’s Lyta Hall.

Lyta Hall, the former member of Infinity Inc. Lyta Hall, the widow of Hector Hall, the former superhero who became temporary yellow-and-hourglass-clad Sandman in a tiny corner of the dream world while Morpheus was still imprisoned. Lyta Hall, the girl who was once known as Fury.

In The Kindly Ones, Lyta is not the trigger of the events that leads to the death of this incarnation of Dream, but she is the bullet. Already unstable, thanks to the death of her husband (for which she still, erroneously, blames Dream), and pushed over the brink by the kidnap of her son Daniel (for which she, again erroneously, blames Dream), she rages against the dream world and with the help of the “Kindly Ones”—aka the Furies of myth—seeks revenge against the dream king. She seeks to destroy him.

And she does. But not before marching against his domain and razing everything in her path. Hempel draws those scenes as if we are looking out from Lyta’s point of view. We see the denizens of the dream world—characters we’ve come to love over the years—brutally slain by what seems to be our own hands. It’s terrifying to become complicit in such actions, but, like any dream, we have no control over what’s happening.

Dream dies, vulnerably to the Furies, because he fulfilled his obligation to Nuala.

It’s more complex than that, though. Thessaly is involved. More involved than we ever would have imagined before the start of The Kindly Ones. And Loki, whom Dream spared from imprisonment in Season of Mists, is the real trigger for all of the destruction that occurs. But there’s some mysterious motivation there as well. And a dozen other characters from previous arcs play important roles in the story as well. It really is a fitting climax for everything Neil Gaiman built in Sandman.

Daniel, magically grown, takes over the role as the dream king. Dream lives, albeit in a different form.

And The Kindly Ones ends with a reflection of what should have been the first panel in the collected edition. It’s the same young woman as before—holding the same yarn—and now we know she’s one of the Furies. And she’s rolling the yarn back up into a ball again, but just beginning to wind it up. From off-panel, a voice says, “There. For good or bad. It’s done.”

And so it is.

Except for The Wake.

NEXT: Friends and family mourn the departed Dream, and Shakespeare writes his final lines.

Tim Callahan would like you to know that Marc Hempel’s “Gregory” books are well-worth tracking down as well. They are nothing like Sandman, but they are odd and hilarious and wonderful in their own way.