Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a space for conversation about recent and not-so-recent short stories. While the format has been the same for the past forty-something columns from me in the series, we’re switching things up a bit based on reader feedback: from here on out I’ll be talking about more stories at less length, so we’ll be covering more than just a few things per month. This means more coverage of more folks, which is something people have been looking for, so—here we are for a fresh take on a familiar project.

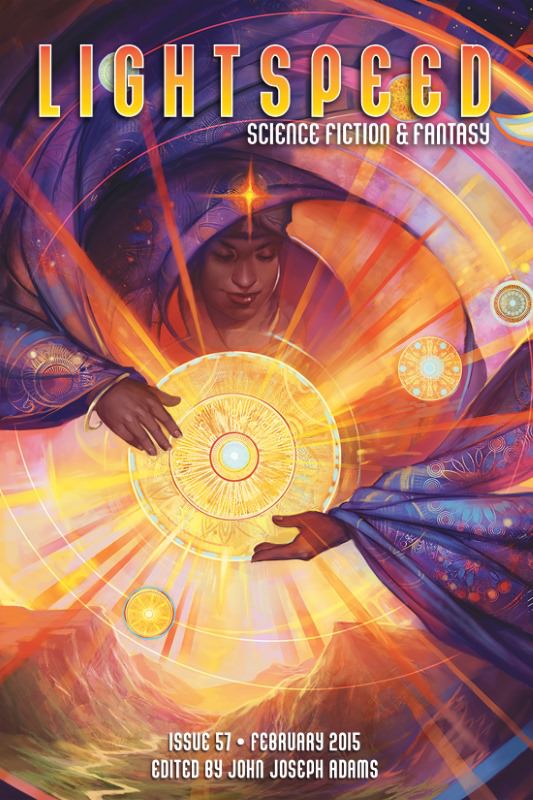

Stories this installment come from various publications, though as this new format goes forward we’ll also often cover whole issues of one magazine (or chunks from a single anthology) as well. This time around, I looked at pieces from Lightspeed, Clarkesworld, and Weird Fiction Review.

“Things You Can Buy for a Penny” by Will Kaufman (Lightspeed, Feb ’15) is a rather direct piece about the costs of magic and wishing. It’s playing with a familiar toolbox of tropes—and, of course, acknowledges that from the very beginning—but it does so in a way I nonetheless found worth sticking around for. The prose is a balance of simple and lyrical, giving it a fairy-tale sort of air. The thing I liked best was that the story ends up leaving the reader gaps (the father’s wish and terms, the son’s fate) that aren’t hard to fill in regardless, because of its allusive strengths. It’s almost a game with the shape of the wishing-well tale. The piece is mostly just asking for the reader to appreciate the back and forth of the wishes and their granting—and to see the threads between stories about wishes, stories about stories, and the power of a penny. Worth a look, and sort of like a warm old blanket with a fresh bit of edging.

“Things You Can Buy for a Penny” by Will Kaufman (Lightspeed, Feb ’15) is a rather direct piece about the costs of magic and wishing. It’s playing with a familiar toolbox of tropes—and, of course, acknowledges that from the very beginning—but it does so in a way I nonetheless found worth sticking around for. The prose is a balance of simple and lyrical, giving it a fairy-tale sort of air. The thing I liked best was that the story ends up leaving the reader gaps (the father’s wish and terms, the son’s fate) that aren’t hard to fill in regardless, because of its allusive strengths. It’s almost a game with the shape of the wishing-well tale. The piece is mostly just asking for the reader to appreciate the back and forth of the wishes and their granting—and to see the threads between stories about wishes, stories about stories, and the power of a penny. Worth a look, and sort of like a warm old blanket with a fresh bit of edging.

There were two stories in Clarkesworld’s February issue that snagged my attention—one a reprint from Jonathan Strahan’s Eclipse Three (2009) and one original. Nicola Griffith’s “It Takes Two” is a novelette about sex and emotional connection originally published in the Strahan anthology several years ago. It’s a science fiction piece with a core interest in the drives and desires of all-too-human people; Cody is a travelling venture capitalist who is looking to land a big deal for her struggling company, while her acquaintance Richard is getting out of the capital game to do hard-line research on biomechanics and behavioral modification. The confluence of those two things ends up landing Cody in love with a young woman from a strip club, and Richard with a lot of unpublishable but significant findings on making people fall in love.

Griffith’s prose is, as always, handsomely transparent and strongly readable—the conversations and the scene-setting details feel concrete and real, while the exploration of what it is like to be in an emotion state are complex and deftly handled. Though it’s a long piece it’s a fast experience: I found myself scrolling ahead almost faster than I was reading. The experiment is unethical and extreme; the feelings each woman has are therefore complex and debatable—but both seem willing, in the end, to dive in and let it happen. Yet, there’s something compelling about that breath of hopefulness or potentiality at the end of a story that has some fairly grimy ethics and is exploring issues of manipulation/exploitation. It certainly maintained my attention.

Griffith’s prose is, as always, handsomely transparent and strongly readable—the conversations and the scene-setting details feel concrete and real, while the exploration of what it is like to be in an emotion state are complex and deftly handled. Though it’s a long piece it’s a fast experience: I found myself scrolling ahead almost faster than I was reading. The experiment is unethical and extreme; the feelings each woman has are therefore complex and debatable—but both seem willing, in the end, to dive in and let it happen. Yet, there’s something compelling about that breath of hopefulness or potentiality at the end of a story that has some fairly grimy ethics and is exploring issues of manipulation/exploitation. It certainly maintained my attention.

The other story I thought it was pointing out also deals with exploitation and all-too-human needs or wants: “Meshed” by Richard Larson. The protagonist is attempting to get a young basketball player from Senegal to sign with Nike and get a neural mesh to broadcast his experiences; his grandfather, however, was a soldier who had the old kind of mesh—the kind used for “puppeteering.” The protagonist attempts to play son against father to convince the son to get the mesh for his dad’s sake—so he can feel what it’s like to play ball again—and it’s a particularly dirty move, one that the reader also feels gross about. It doesn’t seem to work, though it’s hard to tell in the end what the kid’s choice will be.

This one also has the taste of a near-future piece; it’s got that sense of capitalist drive and unethical manipulation, the sources for most of this particular brand of American advertising-and-technology driven dystopia. Except it isn’t dystopic—it’s quite realistic, and also echoes quite a bit with contemporary concerns about the nature of professional sporting and the “purchase” of humans through contracts, endorsements, et cetera. The added complexity of the narrator’s total lack of understanding of what it’s like for a family from Senegal, who have this relationship to the neural mesh technology that he cannot even fathom, makes this more than just a didactic little romp, though. It’s also good at revealing the undercurrents of racism and global politics that imbue capitalist exploitation, and at showing the slippery slope of different peoples’ emotional and financial needs put at odds on an unequal playing field. Short but effective and dealing with interesting issues.

Lastly, there’s “Tin Cans” by Ekaterina Sedia at Weird Fiction Review (Feb. ’15). It’s a darker story than the rest by a significant margin, dealing with the brutal rapes and murders of young women by Lavrentiy Beria during the Soviet era in Russia. The historical record matches up with this story; however, Sedia tells it from the point of view of a man who once drove Beria’s car and now, as an elderly man, works as a night guard at the Tunisian Embassy (once Beria’s home). The moment at the center of the story is the night when he is ordered to stop the car and allows Beria to abduct a young neighborhood girl who he personally likes. He does nothing to save her and is haunted by the knowledge—quite literally.

This is a piece that manages to be simultaneously homely—the old man is a quintessential old-man-narrator, with his asides about his son’s emigration and how the grandkids don’t read Cyrillic—and crushingly, terribly bleak. The girls’ skulls are unearthed and laid out in the garden in the end, which is not much of a memorial; it’s more of an acknowledgement of crimes that could not be revenged or brought justice. The depiction of the hauntings is also graphic and upsetting. The narrator always looks away before the rapes occur, but the lead-up is awful enough by far. The thing that makes the piece’s misery more than just a trotting-out of grim historical fact is the humanity of the narrator, though: his complex reaction to his own accountability, to the impossibility of having stopped a man like Beria, to the horror of the ghosts’ final moments. It’s not a simple emotional register that Sedia is working with, and it’s definitely not for all readers, but I do think it’s doing something necessary—though, yes, very unpleasant—in taking this angle on such a terrible reality.

So, that’s perhaps a harsh note to go out on—but it is a solid, evocative, memorable piece. It’s also chilling, both for its fictional emotional register and for its real-world truths. Weird Fiction Review doesn’t publish as much fiction as some venues, but what it does publish tends to be worth chewing over.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.