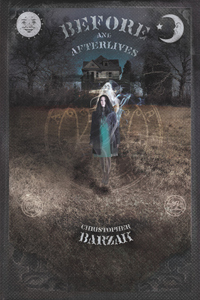

Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a space for conversation about recent and not-so-recent short stories. Our conversational focus this week will be a few stories from a recent collection by Christopher Barzak, Before and Afterlives. The collection, recently published by Lethe Press, is Barzak’s first full-length book of short fiction, following 2012’s diminutive but vivid Birds and Birthdays (published as part of Aqueduct Press’s Conversation Pieces series, reviewed here). Before and Afterlives collects previously published stories spanning from 1999 to 2011 and also includes one piece original to the book, “A Beginner’s Guide to Survival Before, During, and After the Apocalypse.”

I’ve previously discussed one of the stories included in this collection—“Map of Seventeen”—but this time around, I’d like to shift focus to a couple of the stories that I find most emblematic of Barzak’s work as it comes together in this particular book: “What We Know About the Lost Families of ——- House” and “Plenty.” I’ll also spend a little time on the story original to the collection.

“What We Know About the Lost Families of ——- House” is in the vein of a gothic. It has a haunted house, grim family secrets, incest, murder, and most of the other accoutrements. Barzak, though, takes the typical gothic and twists it by giving the narrative through a communal voice: a voice that represents the town itself, the people who make it up and who have observed ——- House’s history. In a move familiar from Barzak’s other stories, which are often densely and carefully constructed, this piece relies on strong, detail-oriented prose with an engaging voice; however, it also relies on the audience’s familiarity with the tropes of the genre to offer a different avenue of exploration.

The story is not told from the point of view of the young woman who marries into the House to communicate with its ghosts, as I’ve mentioned before, so it’s not a typical gothic. Moreover, and more interestingly, though the town’s communal narrative is concerned with rescuing her by the end and with telling us her story as if it’s tragic, it’s impossible to read it the way the townspeople want us to. Their patronizing tone, their willful ignorance and their excuses, render the reader unable to sympathize with their point of view entirely, so we cannot believe or support everything that they do or say. As with the underbelly of resentment, neighborly knowledge, and gossip in any small town, the town in which ——- House is located is conflicted, uneasy, and often judgmental. (Of course, considering the ending, they are perhaps not entirely wrong to want to burn the House to the ground.) This sense of play with form and with tropes is common to Barzak’s short fiction.

And, of course, so are the ghosts: Barzak’s fantastic work is often concerned with the strangeness that lies just outside of everyday life. In Before and Afterlives, as the title implies, there are many sorts of hauntings, not merely of houses and not all of them unpleasant. There is a resonance to these pieces about death and lingering, or about leaving and loss, or all of the above, that makes them quite memorable—just as much as the generic experimentation and the investment in telling different-but-familiar stories with rich characters and settings.

On the other hand, “Plenty” is a different sort of story, one that represents another thread in Barzak’s body of work. It’s set contemporarily, it deals with economic impoverishment, the decay of industrialism, and the fantastic alongside one another, and it offers—more than a plot, though it has one of those too—a developmental arc or moment in a person’s life. “Plenty” and other stories like it in this collection are, in a word, intimate. They are character driven, observational, and often the narrative arc serves a greater provocative emotional arc. In this piece, where friends come apart and together based on differences in their personalities and life choices, a fantastical table that makes feasts—but only for someone so generous as to want to give them away—helps the protagonist to see what he had been unable or unwilling to see about his good friend’s inner nature. The other man is able to reconsider his own distant friend’s apparent selfishness through his gift of the table, his willingness to part with it and to keep its secret for the betterment of the suffering community. (Put like that, it’s almost a parable.)

These characters and their realistic, unfortunate misunderstandings and misapprehensions are the focus of the tale. When Barzak is studying people, telling us their stories, his work is powerful; these stories incite a great deal of consideration about others, their needs, and the functions of living in a world where industrialism in the West is decaying and whole cities are ground under by poverty. Barzak’s background in an Ohio city of similar experience adds a distinct level of solidity to many of the stories set in or around that milieu, and offers the reader a glimpse into the sort of survival that those places require.

These two stories represent interests and tendencies that are clear throughout Before and Afterlives. The majority of Barzak’s stories as represented here could be shifted into one group or the other, with a few lingering somewhere in between. The treatment of the fantastic in both is often naturalistic, rather than surreal or over-the-top unreal. However, in one set of stories the concern is generally with the form and function of story itself, with what can be done in certain kinds of restraints to tell new kinds of stories or to explore new facets of the familiar. In the other, the focus is character and place, and the story flows along moments-in-the-life with most of its attention devoted to realistic detail and intimate observation. These are gentle stories, though often upsetting, and their narrative shapes tend to be similar; they end on contemplative notes.

There is also, finally, the story fresh to this collection: “A Beginner’s Guide to Survival Before, During, and After the Apocalypse.” This story wavers between the poles I have just laid out. It’s immersed in a generic structure (the apocalypse survival story) that is then played with and altered, showing the delight in experiments in form in content familiar from “What We Know…,” but it’s simultaneously a closely observed, personal, and mundane story about survival and self-identification. Barzak, after all, is not a one-trick writer. His prose, even in this rather short piece, is detailed nearly to the point of lushness—but not too much so.

Before and Afterlives reveals a series of confluences and concerns in his short fiction, and as such, works remarkably well as a coherent collection. It’s a thoughtful, pleasant, and lingering sort of book: many stories, many lives, and many deaths to consider—as well as how these things, and the people that power them, intersect and reflect reality in a fantastical mirror.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.