Miriam is a drifter with an unusual gift: when she touches someone skin to skin, she sees a brief vision of the circumstances of that person’s death. It could be decades into the future or later the same day. Some deaths are accidents, some are of old age. Regardless, the first time Miriam touches someone, she sees when and how that person will die.

She occasionally uses this gift (or curse?) to loot some cash from the recently or soon-to-be deceased, which allows her to stay in motels and keep a steady supply of booze on hand to numb herself, but one night her life changes drastically: when she touches a friendly trucker giving her a ride, she sees not only that his death will be a violent one, but also that the very last word he utters is her name…

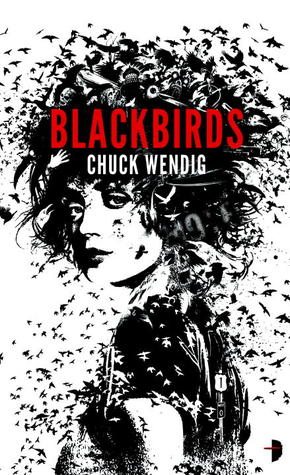

Blackbirds took me by surprise. What originally drew me to the book is the stunning cover by Joey Hi-Fi (as far as I’m concerned, it’s more than award-worthy) but the book’s blurb somehow sounded hokey to me, one of those ideas that seemed a bit too familiar even though I couldn’t put my finger on exactly where I’d seen it done before in recent fantasy. It seemed like something that could go horribly wrong or turn into a good plot, depending on how it’s handled.

Dear reader, I’m here to tell you: Chuck Wendig handles it exceptionally well. He turned my initial slight skepticism around in no time, well before I reached the scene described in the plot summary. This is one of those novels that sucks you in and doesn’t let you off the hook until you’ve turned the final page.

Part of the reason for this is, well, the hook: you’re spoon-fed a scene that’s, if not the final one in the novel, at least probably close enough to the end to make you curious: what exactly led up to that horrible situation, and how is the author going to resolve it? Chuck Wendig essentially works his way towards an ending you already know, which is a tricky technique to attempt because, well, how do you maintain the reader’s interest?

A big part of why this works out so well is Miriam. She’s an opportunistic, bitter, abrasive loner who takes advantage of people who are about to die. While she does this, she’s not afraid to rub it in and generally be as unpleasant as possible. As she travels around, she meets a range of other people who, for the most part, are highly unlikeable individuals themselves: rootless drifters, criminals, con men. The one notable exception is Louis, the man who says her name right before he dies, and even though he’s maybe the most relatable character in the book, he has one huge strike on his model citizen scorecard too. In case it wasn’t abundantly clear yet: this may not the book for you if you tend to prefer likeable characters.

All of these people meet and live on the periphery of towns: motels, truck stops, diners, bars, the places frequented by people who don’t have a place of their own to go to. These settings make the novel’s atmosphere even more grim, as if the reality in which people live in actual homes is a fantasy realm. In Blackbirds, all that remains is the faceless, grey area on the edges of cities, where people bed down in temporary rooms and eat in roadside diners and never get the chance to make any kind of meaningful connection with their environment.

Their relationships are often equally fleeting. For the most part, they’re all just passers-by in each other’s lives, which makes the highly intimate glimpse Miriam catches of their deaths even more stark and poignant. The interactions we see in Blackbirds are mostly unpleasant: meaningless sex, bar brawls, verbal abuse, theft, torture. And death. People live and die alone, and Miriam does her best not to get involved in any other capacity than as an opportunistic scavenger. Things seem to go wrong whenever she goes beyond that.

If all of this sounds stark and grim, well… it is. At the same time, we learn enough about Miriam’s past, in a series of Interview with the Vampire-style interludes, to explain some of her motivations. There are redeeming qualities. Even better, this information becomes more than just window-dressing as the story progresses. Add to that some welcome touches of humor—although admittedly often of the bleak, even gallows, variety—and you’ve got a novel that’s dark as dark can be, but still immensely entertaining.

It would be so easy for an author to self-indulge with this type of story, going for moody, high-goth flowery prose, but instead what you find here is the polar opposite: a tight, spare narrative that doesn’t have too many wasted words. Maybe some of Miriam’s verbal tics are played up just a bit too much at times, but that’s really just part of her character: she’s not averse to acting the hyper-verbal brat to get under people’s skins. It may be over-done once or twice, but for the most part it works out well. The term “verbal sparring” is surprisingly appropriate for many of the dialogues in this novel.

So. If you don’t mind grim and gritty novels full of death, violence, and nihilistic loners, you really should consider picking up Blackbirds by Chuck Wendig. It’s a short, sharp tale that’s consistently captivating and a pure, dark delight from start to finish.

Stefan Raets reads and reviews science fiction and fantasy whenever he isn’t distracted by less important things like eating and sleeping. His website is Far Beyond Reality.