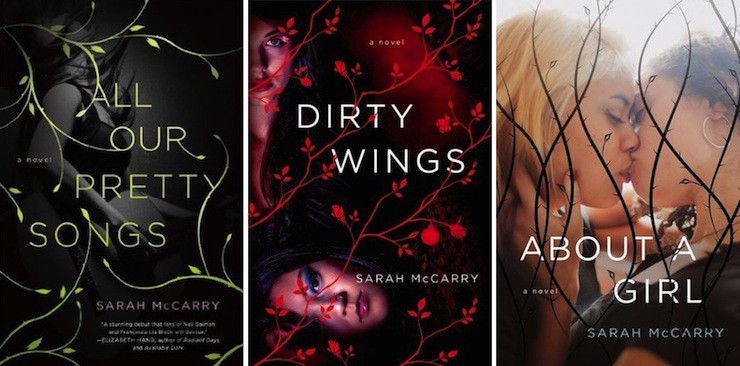

According to their marketing, Sarah McCarry’s first three novels are Young Adult books, though there is very little that’s solely young about them. All Our Pretty Songs. Dirty Wings. About A Girl. They form a triptych, as rich and deep and strange a tapestry as any piece of literature I’ve ever come across. Drenched in mythology, saturated with metamorphoses, they’re books about liminality. About the edges of things. About the border between youth and adulthood, between the familiar and the strange, between being and becoming, loss and belonging.

They’re books about transition and transformation, and it’s far from astonishing that the main character of About A Girl is offered a copy of Ovid’s Metamorphoses as she finds herself falling in love with a girl who is also a monster, who is also a version of a woman in a myth: no, it’s no surprise at all.

So, as she counted in her well-stored mind

the many tales she knew, first doubted she

whether to tell the tale of Derceto,—

that Babylonian, who, aver the tribes

of Palestine, in limpid ponds yet lives,—

her body changed, and scales upon her limbs;

or how her daughter, having taken wings,

passed her declining years in whitened towers.

Or should she tell of Nais, who with herbs,

too potent, into fishes had transformed

the bodies of her lovers, till she met

herself the same sad fate; or of that tree

which sometime bore white fruit, but now is changed

and darkened by the blood that stained its roots.— Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.43-52, trans. Brookes More

All Our Pretty Songs, Dirty Wings, and About A Girl are saturated in conscious resonance with Graeco-Roman mythology, layered over—or under—with echoes of Christian narratives of temptation and fall. These are each, in their way, Orphic narratives: bound up in music, but tied, too, to the Orphic descent to the underworld. In myth, Orpheus is a poet and prophet, who can charm wild animals, rocks, trees, even Hades himself with his music. In one version of the story, he voyaged with the Argo. He goes to the underworld to redeem his wife Euridike—and fails. And at the end of his life, Orpheus is torn apart by women who follow the rites of Dionysos.

McCarry’s characters are torn in different ways.

In Classical mythology, nothing ever ends well for mortals with godly gifts. McCarry is slightly kinder to her characters. Slightly. But one of the themes running through this triptych is about making choices and assumptions, and about who pays the price for those choices—and about how you can’t take them back. The road to hell is wide and easy, and if you make a deal with the devil, you ought to be sure of the terms. (And you can’t save everyone, especially not from themselves: sometimes the only person you can save is yourself.) The underworld descent is a reified metaphor, and one that works on several levels. For McCarry uses a kind of poetic realism, a magical realism: the world of her characters looks ordinary and everyday until it doesn’t, until things turn aslant and strange.

All Our Pretty Songs, Dirty Wings, and About A Girl are novels about three generations of women. Three generations of a family, if we’re defining family a little outside the standard parameters. Though All Our Pretty Songs is first in publication order—and is the keystone of the triptych as a whole—Dirty Wings, published second, is first in terms of the internal chronology. Each of these books are about young women: young women as friends, as sisters, as lovers, as people making choices.

And the language. Bloody hell, McCarry’s prose. It’s lyrical, poetic, at times lush — at times brutally straightforward, but always with the rhythm of poetry behind it. These novels are worth the investment in reading time for the prose alone—although they’re worth it for much more than that. The mythic resonance goes deep: About A Girl adds layers to Dirty Wings that only seem obvious in retrospect, as Dirty Wings does for All Our Pretty Songs. As a set, as a triptych, this is an immensely clever piece of art, and an immensely playful one. It plays with language, with myth, with style. It plays your bloody heartstrings with downright Orphic virtuosity.

So I guess what I’m saying is: they’re good books. Read them.

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books. She has recently completed a doctoral dissertation in Classics at Trinity College, Dublin. Find her at her blog. Or her Twitter.