The literature of the fantastic is a fruitful place in which to examine gendered questions of power. People have been using it to talk about women’s place in society (and the place of gender in society) pretty much for as long as science fiction has been a recognisable genre. Joanna Russ and Ursula Le Guin are only two of the most instantly recognisable names whose work directly engaged these themes. But for all that, science fiction and fantasy—especially the pulpishly fun kind—is strangely reluctant to acknowledge a challenge to participation in demanding public life (or a physically ass-kicking one) faced primarily (though not only) by women.

Pretty sure you’ve already guessed what it is. But just to be sure—

Pregnancy. And the frequent result, parenting small children.

As I sit down to write this column, my brain is hopping around like a rabbit on steroids. (Metaphorically speaking.) For me, it’s the end of January, and I’ve come home from a flying visit to New York and Philadelphia to attend part of an Irish political party’s national conference as a participating member,* and so politics and the difference between cultures that may have surface similarities are somewhat on my mind. And, too, the social assumptions and contexts that mean women are underrepresented in politics and leadership roles, both in real life and in fiction.

New Zealand’s Labour Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern joined the ranks of history’s handful of female premiers last October, and now she’s only the second democratically-elected premier in modern history to be pregnant and plan on giving birth while in office. That’s a striking number: number two in history.

Science fiction and fantasy is seldom interested in people’s reproductive lives from a social perspective, except when it’s in the context of dystopian social control. Childbearing and child-rearing are central to many people’s life experience, which makes it more than a little odd that I can only think of perhaps two or three SFF novels that, without being entirely focused on it, incorporate pregnancy and reproductive life as a central part of their narrative. Lois McMaster Bujold’s Barrayar is one of them. Cordelia Naismith Vorkosigan’s pregnancy (both in her body and in the uterine replicator) and her feelings about children and Barrayar is central to the narrative—which involves, among other things, civil war, and Cordelia herself playing an important role in bringing that civil war to an end. We find reproductive concerns (as well as conspiracies, spies, and the fragile environments of space stations) at the heart of Ethan of Athos, too, where a young man from a planet inhabited only by men** must go out into the wider universe to bring home ovarian tissue cultures so that his people can continue to have children.

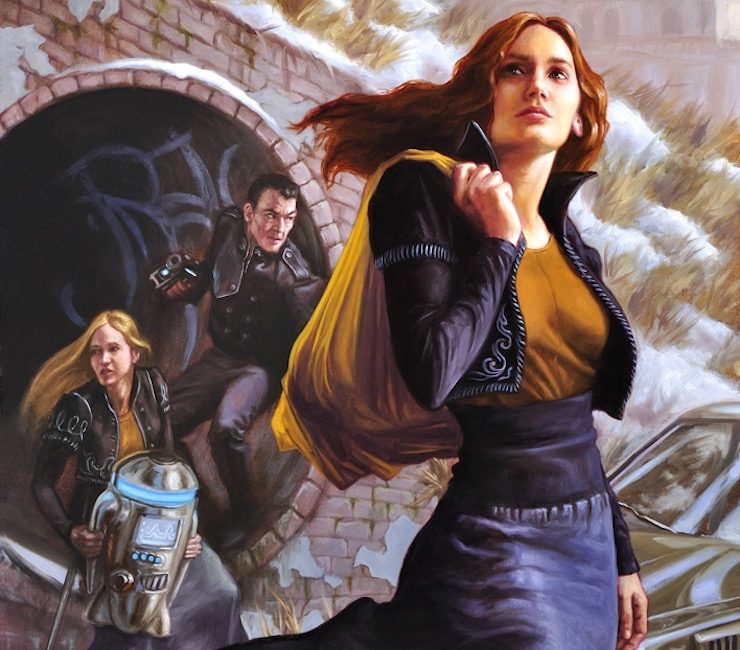

And pregnancy, as well as politics, forms a significant part of the first science fiction novels I ever read: Timothy Zahn’s Star Wars: Heir to the Empire, Dark Force Rising, and The Last Command. Heir to the Empire and Dark Force Rising, in fact, stand out for being action novels in which one of the major protagonists—in this case Leia Organa—must deal with being pregnant, how the people around her react to her being pregnant, and the ways in which being pregnant increasingly changes her ability to do things (like participate effectively in fights and chases) which when not pregnant she took for granted. I’ve looked ever since the mid-1990s for other portrayals of pregnant diplomats who can kick ass and take names at need, and found myself surprisingly disappointed.

In real life, we’re pretty terrible about articulating and addressing assumptions about childbearing and child-rearing. We are, in fact, distressingly bad as societies about facilitating the participation of people with primary child-rearing or caregiving responsibilities in all aspects of social, community, and political life: it’s not really surprisingly that our fictions tend, as a rule, to avoid looking closely at the circumstances that make it easy—or conversely, hard—for pregnant people or people with small children to be fully a part of public and community life. What does a world look like if the society doesn’t assume that childbearing and child-rearing work is (a) a private matter for individuals, (b) isn’t assumed to be primarily the responsibility of women, (c) isn’t often outsourced by wealthy women to poorer ones? I don’t know.

I don’t particularly want to read an entire novel about the economics of child-rearing. But I’d like to see more books, more SFF stories, that consider its place in the world and how that affects people in their societies.

Have you read novels like this? Have you any recommendations? Thoughts? Let me know!

*Where I met a reader of this column who turns out to also be related to my girlfriend. Ireland is a small place. *waves to Siobhán*

**There is no social space on that planet for trans women or nonbinary people.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, is out now from Aqueduct Press. Find her at her blog, where she’s been known to talk about even more books thanks to her Patreon supporters. Or find her at her Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.