People often fear (or dislike, or get stressed out about) change—in culture, in fandom, in fiction, in science… and they like to make their displeasure known. For the record, I find complaining that the inexorable passage of time has transformed fandom or other realities as ludicrous as assessing people by their preferences in slide rules… but I suppose shouting at clouds fills the empty hours.

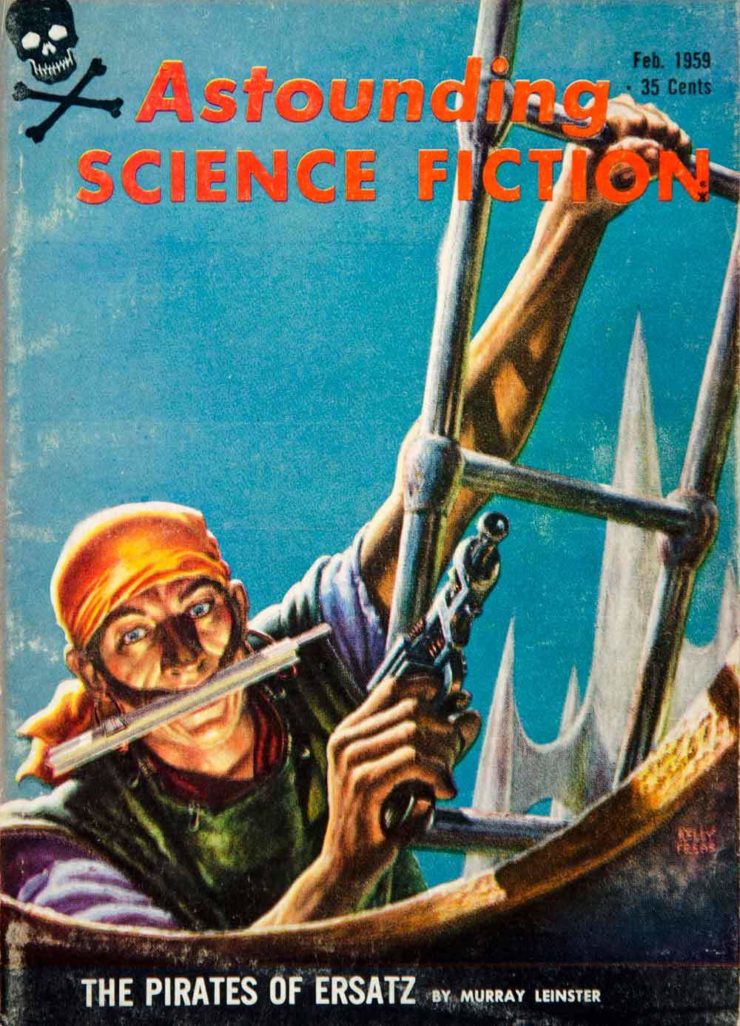

Still, it must be said: slide rules are pretty cool and way important to the history of science fiction, as evidenced by the ray gun and slide rule toting space pirate on the cover of Astounding Science Fiction.

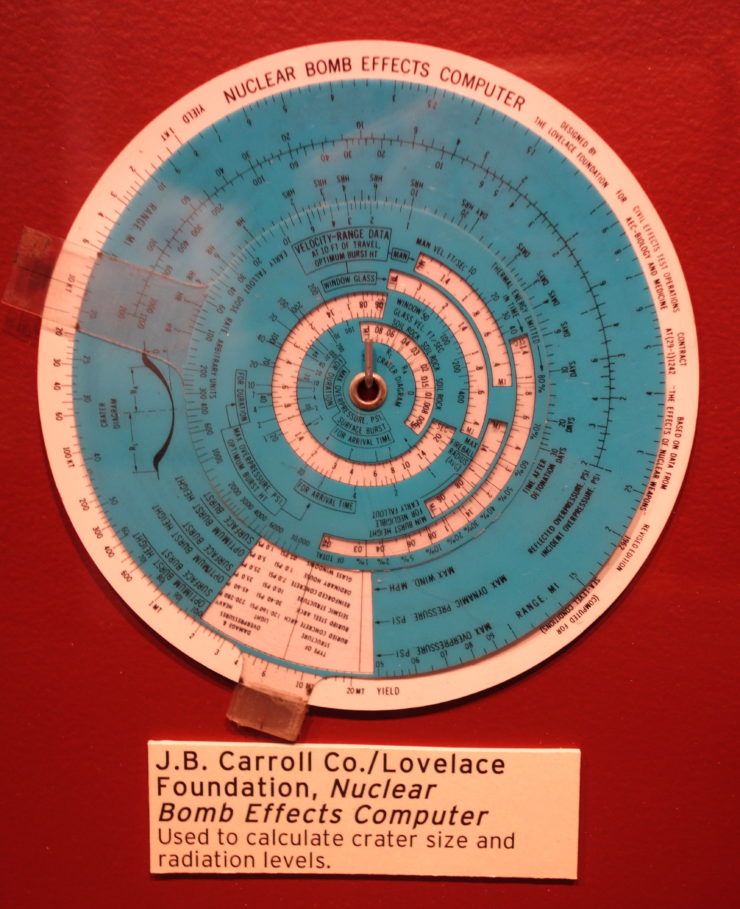

Like so many of us, I cut my teeth on a Pickett. Pickett made fine slide rules and I still know where mine is. Hence you may be surprised to discover that the slide rule I have used most often was not one of my Picketts. It was this magnificent embodiment of the Cold War:

This circular slide rule was included in Samuel Glasstone and Philip J. Dolan’s popular children’s book, The Effects of Nuclear Weapons, which along with classics like Hershey’s Hiroshima and Lapp’s The Voyage of the Lucky Dragon, made growing up in the 1960s the delightful, carefree experience it was. Why fret over grades or fitting in with the school’s social hierarchy when at any moment a Russian bomber (or missile) might reduce one to a shadow on a wall?

Of course, as Effects and that delightful gem of a calculating device made clear, instant incineration is a fate only a small fraction of the casualties would enjoy. A few twirls of the slide rule drove home the fact that one was much more likely to be smashed by a falling wall or burn to death in a blazing building. If one was lucky, one might find a refuge in which to wait out fallout decay. (If one were even luckier, the refuge would be stocked with succulent neighbours.)

The one downside of Effects and resources like it is that they ruin works like On the Beach for informed readers. Fallout does not act as Nevil Shute has it act, nuclear bombs are a lot more expensive than he supposed, and while his tale of people grappling with their inevitable mortality is still engaging, one has to wonder why nobody tried to dig a fallout shelter. Familiarize oneself with the actual effects of nuclear weapons and the fictional accounts often disappoint.

Of course, authors could familiarize themselves with the facts of nuclear weapons before writing post-apocalyptic tales, but that might be asking too much.

Time marches on. We still live in a world where even now a Russian or American ICBM may be on its way to rearrange our living room whilst transforming us into a singed Jackson Pollock painting. It’s quite possible that some picayune dispute in the Middle East or Asia might balloon into a catastrophe that would leave us in a state of permanent Mad Max cosplay. That’s still true. What has changed is that books that were formerly only available on paper are now found online. My beautiful circular slide rule has been turned into software.

Alex Wellerstein did Effects’ slide rule one better by combining the models behind it with modern mapping software. No more wrestling with paper maps, measured lengths of string, and markers! Thanks to Nukemap, you can select a city, a yield, the effects that you want to track, then click detonate and, voilà! Results in less time than it would take for a thermonuclear detonation to bring the house down around you. It’s an addictive experience, as proved by the fact people have used the site over 177 million times.

Isn’t the future a wonderful place?

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a finalist for the 2019 Best Fan Writer Hugo Award, and is surprisingly flammable.