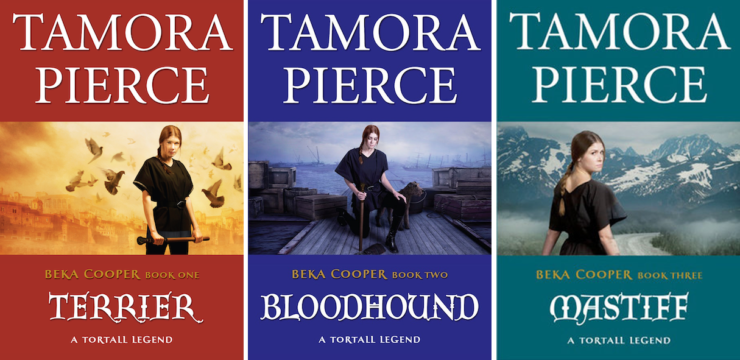

The Provost’s Dog trilogy by Tamora Pierce tackles the difficult relationship between the police force and civilians in a fantasy medieval society. Sixteen-year-old Rebekah Cooper is a police officer in a community where the police are still forming their own moral code; therefore, the road between law and lawlessness is full of twists and turns. Criminals are common in the poor neighborhood Beka patrols, and her job is made more difficult by criminals assuming they deserve something from the upper classes.

Beka Cooper’s stories are part of Pierce’s young adult fantasy Tortall universe, named after the fictional country where much of the action takes place. Pierce’s first (and arguably most famous) series, Song of the Lioness, features Alanna of Trebond, a noble girl, as she fights to train as a knight in a time when only men are allowed to do so. Lioness focuses on the nobility, while Provost’s Dog skirts around it, dealing mostly with commoners in the poorest section of the capital, the Lower City of Corus.

Beka did not grow up in high society and willingly works with the poor, facing child murder, poverty, domestic abuse, and the slave trade throughout her rounds. At the age of 8, Beka tracked down a man who was beating her mother and managed to deliver his gang to the Lord Provost, who took in her family in return. Afterwards, she wanted to be a Provost’s Guard, and the epistolary trilogy consists of her diary entries describing her work on the streets. As a former ward of the Lord Provost, Beka is careful to avoid using that high connection to rise quickly in the ranks, unlike some police officers today.

The first novel, Terrier, opens with Beka waiting to be assigned to her training officers. The scene is descriptive and slow, until someone comes into the station and asks, “Be there word of who left old Crookshank’s great-grandbaby dead in the gutter?” Beka is immediately reminded that the work she is training for has a purpose, because terrible things happen every day in the Lower City.

The topics explored in this series are deliberately dark and unnerving, despite the target age range being young adults. Fantasy is so often about the next great adventure or mystery, that it’s important for readers to be reminded that fantasy is usually settled in history—messy, awful history, driven by ordinary people as much as politicians or nobles. Beka tells her tales from a place of relative safety, but with her own poverty-stricken childhood looming over her shoulder.

Beka grew up in the slums of the Lower City and continues to live there while working as an officer since she’s comfortable with what she knows. Class issues are more inherent in this series than Pierce’s others. When the poor of the Lower City are all striving together, small differences like a suddenly new necklace or a better job make a big difference. Nobility play a small role in Beka’s adventures, and they are treated with appropriate distance to indicate the social gap. Whenever Beka meets with a noble, there is a general sense that their worlds and lives are miles apart, and it’s better that way. Tortall has created a rigid class system for itself, and most don’t try to change it too drastically. Lord Gershom, the Lord Provost, is respected by all the Guards, but comes off as a rarely seen executive rather than a hands-on boss due to his absence from their daily lives and duties. All Guards must report to the magistrate, a noble, on court cases every week. Beka has to be careful to address him properly, avoiding slang and landmarks only commoners would know. She changes her speech to interact with him, and though that’s part of her job, it’s also an aspect of dealing with the class system. While even Beka’s training officers know the city she lives in, her friends, and the general shape of her life, nobles don’t, and so she can’t relax around them. There is always separation and caution, tempered with respect.

Beka has four younger siblings, and wants to see them rise in the world, but she has realistic expectations for how high they can go. As a child from the slums who was rescued by a rich man, she knows that rescue doesn’t go further than a place to live and an education. In this series, when a character wants something beyond their means, they’re usually willing to do something unspeakably awful, such as murder, to get it. There is very little class mobility in this world; when a character does drastically rise in status, it’s usually for an extraordinary good deed, like rescuing the prince. The character who has delusions of grandeur in Terrier turns out to be the villain; when she was breaking her back with physical labor, she couldn’t stand the thought that other people might have treasures nicer than she did, and stole their children as ransom. In a way, it’s disheartening to find a series that relies so heavily on a stratified social structure, but on the other hand, a cynical person would say it’s impossible to achieve upward social mobility in most societies anyway. Is it better to fight for a few feet of ground or to just live your life as best you can?

Buy the Book

A Master of Djinn

Pierce reveals her most effective worldbuilding in Provost’s Dog. Slang is prominent and infuses the narrative with detail. For example, the Guards are called Dogs, while trainees are called Puppies; Beka’s kennel, or station, is Jane Street. Though Puppies are still in training, they’re expected to carry their weight when on the streets, either by helping in fights or by running after thieves. The mentorship between training Dogs and Puppies depends heavily on how well they all get along as people, since their job is to walk the streets for hours while looking for trouble. It is noted that of the Puppies stationed in the Lower City, one-quarter quit or die within the first year of service.

When Beka and her training officers, Goodwin and Tunstall, are on a case, they often ask citizens for information; being asked flat-out affects how people speak and what they reveal. Dogs also have paid informants. The civilian populace generally respect the Provost’s Guard, as well as their ability to stay alive on streets where swords and knives are common. Dogs carry wooden batons with a lead core; they can do damage, but they don’t kill, unlike a knight’s sword. Dog work isn’t usually done with the intent to murder, after all. However, police brutality isn’t brought up as a major theme in Provost’s Dog; generally, suspects really are guilty, and though the wider world does have dark-skinned people, the issue of racism isn’t addressed. When the bandits have sharp knives and will gladly skewer you to the wall, it’s easy to hit them in the kneecaps with your baton. It certainly beats dying.

When Beka helps Tunstall and Goodwin break up a brawl between country boys, citizens in the crowd who knew her as a child congratulate her. Goodwin cautions her not to let the attention go to her head, but also to be aware of the fine line all Dogs must walk. “You think you’re their gold girl now, Cooper? Wait till you have to take in someone they love, someone popular,” she says. “You’ll learn fast enough whose side they’re on.” Since this community is so small, citizens know who is being arrested and are invested in what happens; the magistrate’s court is open to the public. Beka’s experience is that people appreciate the Dogs for dealing with the dregs of society, but Lower City denizens can be particularly vicious when one of their own is taken, either through murder or the Guard. Beka loves the Lower City for those who live there, and for the fact that there’s always something happening with people caught up in the action; the Lower City is alive for Beka. She is an officer because she wants to protect her city. Bad things can happen, however, as people fight to get out of poverty in the wrong ways. Despite the subject matter, this series posits that people are generally good, and are forced into unsavory behavior by circumstance or negative emotions such as jealousy. With magic that allows the Guard to tell when someone is lying, most criminals are guilty. Those who aren’t are mainly foolish, and learn from the experience.

The Guards are still making up their police work as they go. They accept bribes, both individuals and those of the local thieves’ den called the Court of the Rogue, which was originally formed to protect the city’s poor. Beka and her fellow trainee Ersken are friends with criminals who serve the Rogue. The novel acknowledges that there is a system in place that makes these jobs necessary; there is no condemnation for crime here. Despite the potential for problems, they all manage to stay friends by avoiding discussion of their work. Bribes are deemed acceptable if Dogs perform the asked-for task; too many unfulfilled bribes can get a Dog killed. However, if a Dog is smart, careful, and motivated, they can succeed in the worst conditions, as Beka, Tunstall, and Goodwin strive to do. Again, bribes are accepted because they spread money and information around for the Dogs. This world is messy and complicated, and the rules are still being written.

Beka Cooper and her fellow Dogs of the Jane Street kennel work with the most poverty-stricken in the Lower City, and their shift, the Evening Watch, gets the worst of the robbers and murderers who are out and about. They do their best in a society that both accepts and refutes law enforcement; for example, the slave trade is still legal in Tortall. Despite this, Beka always fights to do her work for the Lower City, as all officers should. This is a society—and a police force—still in the making, in spite of what they have managed to create. Even in our modern society, laws are still being written and rewritten. There is always space for change.

Noemi Arellano-Summer is a journalist currently working in the Los Angeles area. She has experience as a writer, editor, copy-editor, photojournalist, and arts critic. She is passionate about arts, history, culture, entertainment, film, and literature.