Whatever else Andre Norton did during the Golden Age of science fiction, writing apolitical “pure” adventure was not in her wheelhouse. She had her favored protagonist: young, male, orphaned and alone, struggling to make a go of it in a hostile universe—and her favorite settings: backwater planets full of inimical alien life and mysterious ancient ruins with lots (and lots and lots) of subterranean chambers and passages. Oh, she loved her underground traps and desperate escapes. Her pacing was breakneck, her plots full of wild twists and turns.

And she had an agenda.

She always had something to say about the flotsam of war, the human costs of conflict both planetary and interstellar. Her universes teetered on the edge of decadence and sat on top of millennia of war, colonization, and conquest. Her human characters were sometimes default-white (and usually of Nordic extraction; like Poul Anderson, she had a predilection for that particular heritage), but more often either mixed race or explicitly not white.

The future, she made it clear, was not white-bread or English-speaking. Nor would Earth, in the end, be the dominant world. It might actually not exist at all, or be bombed to slag either by its own people or by alien invaders.

In the series of novels set in or around the pleasure world of Korwar, Terra is still extant but has played one too many games of interstellar war and lost its claim to primacy. Capitalism rules, income and class inequality is extreme, the Thieves’ Guild is a major political and economic force, and war refugees have flooded into the slums called The Dipple.

In 1961 when this novel was published, the memory of World War II was still fresh, and all of these elements may have seemed slightly quaint in the flush of the postwar boom—in the sense of, “We’ve moved past this, but let’s not let it happen again.” In 2018, they’re strikingly and almost painfully timely.

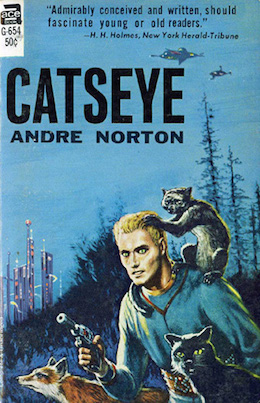

Catseye offers a young Nordic protagonist (in so many words: he’s from a ranching world called Norden) named Troy Horan. His world was conquered and its people dispossessed; his father died in the war and his mother, as usual, is conveniently dead. Troy just barely scrapes a living in classic Norton-protagonist fashion, until, also in a classic plot development, he’s given a job as a general dogsbody for a purveyor of exotic animals to the rich and dissolute.

He’s quickly caught up in a nefarious plot to use telepathic Terran mutant animals as spies and assassins. The animals’ spy-handler turns out to be his boss, using a mechanical device that enslaves them to his commands. Troy is able to communicate with the animals without artificial assistance, and being a ranch kid and an animal lover and an overall standup guy, he takes their side.

This unfolds rather slowly while Troy settles in to his new job, meets the animals and discovers his telepathic abilities, clashes with a senior employee named Zul, and worries about whether his seven-day contract will be renewed. He quickly makes himself indispensable by being the only person in the place who can handle the fussel hawk (a Norden native species) that is going out on trial to a hunter from the Wild—the extensive, non-citified region which is controlled by a federation of hunter Clans. Troy travels with the hawk, comes to like and almost trust Rerne the Hunter (whose name no doubt is an echo of the Terrestrial Herne), and learns about the heavily embargoed alien ruins which are (inevitably, this being a Norton novel) located in the Wild.

In the meantime Troy discovers that the first Terran telepath he met, the kinkajou whose owner has just died mysteriously, has disappeared. The second two, a pair of cats, are intended as pets for a (female!) head of state. The kinkajou’s cage is now occupied by a pair of foxes, also destined to be placed with one of the planetary elite. All of these creatures, he’s told (falsely as he discovers later), can only eat special food provided by the shop, and it’s while delivering a supply of this to the late dignitary’s estate that Troy happens to come into mental contact with the kinkajou.

Then comes a huge reversal, and the action speeds up. Troy’s boss is killed, and he makes his escape with all five Terran animals. He’s been framed for the murder, and everybody is after him, from his rival in the shop to the Thieves’ Guild to the planetary Patrollers—and, once he breaks out into the Wild, Rerne and the Clans as well.

Of course he crashes in the ruins, where he learns a few of its secrets (underground, of course) and uses them to defeat his enemies and work out a deal with Rerne and his people. Troy trusts no human, and that’s to his advantage. In the end he’s a free man, and his animal companions are his full partners, with equal stake in what happens.

There is one squirmy bit for the reader in 2018—the evil Zul, who is described as stunted, yellow, and ugly inside and out, turns out in the end to be a Terran “primitive,” a Bushman. The way he’s described and the role he plays represents the kind of casual and ingrained racism that around here we refer to, euphemistically, as “of its time.” And that’s after the echo in my brain of the much later, iconic line from Ghostbusters, “There is only Zuul.”

But to balance this, Norton has a lot to say about the way refugees and homeless people, and the poor in general, are treated. She’s also explicit about the theme of the book, which is the role of animals as pets. The five Terran animals are highly intelligent and able to communicate telepathically with each other and with humans who have the right technology or mental gifts.

Kyger the shop owner uses them as tools, with no consideration for their personal wishes. Troy quickly learns not to do this, and rebukes himself when he falls into the human habit of thinking animals exist to serve man. These creatures are full partners in the adventure, and they make it clear that they will work together for mutual benefit but they don’t take orders. He can ask. He can’t compel.

This is pretty radical. It’s hard for Troy, and the rest of his universe isn’t set up to cope well with it, though the Clans are at least willing to entertain the notion.

What Norton doesn’t do, and to be fair it’s beyond the scope of the novel, is take the next step and address the issue of sentience in general. It’s easy enough for her humans to accept aliens as equals in intelligence (or even superiors in the case of the Zacathans), and there’s a lot of discussion in the Solar Queen books about how the presence of intelligent native life renders a planet inaccessible to human colonization. The Janus novels touch on this very lightly, but don’t follow through.

But here is a different and even more complicated question, which is what to do about creatures from Terra itself who have been modified, or who have mutated to be fully sentient in the human sense. When does a pet stop being a pet and start being a moral and legal equal? Where do we draw the line?

That’s what Troy faces, and what he forces the powers of his world to confront. On the one hand, these creatures are guilty of murder and espionage. On the other, they were coerced. On the third, what right did anyone have to use these fully sentient beings as tools? And on the fourth (since they’re all quadrupeds), what happens next? How will this universe deal with all the other Terran animals being used this way on other worlds?

Buy the Book

Binti

That’s where Norton backs off, as she did with the Janus books. Here as there, she sets up scenarios with major ramifications, but she seldom if ever pursues them. She stops short of it, focuses on the chases and the blaster battles and the underground ordeals, and closes down the plot before getting into the really difficult stuff.

But then her audience at the time was presumed to be tween and teen boys, for whom the chases and the blasters were everything. To them, I’m sure, psychological complications and deep ethical dilemmas would have totally got in the way of the story.

It is a nice adventure yarn. I found it highly readable, lots of fun, fairly accessible protagonist, and seriously cool animal companions. Good one, as these early Nortons go.

Next I’m off to another early set of novels, starting with The Crossroads of Time (1956). Time travel, whee!

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Her most recent short novel, Dragons in the Earth, a contemporary fantasy set in Arizona, was published by Book View Cafe. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies and space operas, some of which have been published as ebooks from Book View Café. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.