It’s important to remember that the term “space opera” was first devised as an insult.

This term, dropped into the lexicon by fan writer Wilson Tucker, initially appeared in the fanzine Le Zombie in 1941. It was meant to invoke the recently coined term “soap opera” (which then applied to radio dramas), a derogatory way of referring to a bombastic adventure tale with spaceships and ray guns. Since then, the definition of space opera has been renewed and expanded, gone through eras of disdain and revival, and the umbrella term covers a large portion of the science fiction available to the public. It’s critical opposite is usually cited as “hard science fiction,” denoting a story in which science and mathematics are carefully considered in the creation of the premise, leading to a tale that might contain more plausible elements.

This had led some critics to posit that space opera is simply “fantasy in space.” But it isn’t (is it?), and attempting to make the distinction is a pretty fascinating exercise when all is said and done.

Of course, if you are the sort of person who terms anything with a fantastic element as fantasy, then sure—space opera falls into that sector. So does horror and magical realism and most children’s books and any other number of sub-genres. The answer as to how much any given qualifier for a sub-genre truly “matters” is always up for debate; pairing it all down until your favorite stories are nothing but sets of rules is a tasking journey that no mortal deserves to suffer through. What does it matter, right? We like the stories that we like. I prefer adventurous stories with robots and spaceships and aliens, and nothing else will ever be as good to me. I enjoy the occasional elf, and I love magic, and fighting against a world-ending villain can be great sometimes. I also adore it when real-world science is applied lovingly to a fictional framework. But if I don’t get my lasers and my robots and poorly considered space wardrobes in regular doses, the world will not turn properly.

Which means that something about the genre is distinct—so what is it? Highlighting the variations can make a heaping difference in helping people explain what they enjoy in fiction, and to that end, the definition of space opera has had quite a journey in the popular lexicon.

To start, a word from The Space Opera Renaissance, written by David Hartwell and Kathryn Cramer. Their book defines the genre as “colorful, dramatic, large-scale science fiction adventure, competently and sometimes beautifully written, usually focused on a sympathetic, heroic central character and plot action, and usually set in the relatively distant future, and in space or on other worlds, characteristically optimistic in tone. It often deals with war, piracy, military virtues, and very large-scale action, large stakes.”

Plenty of those ideas apply in a wide spread of fantasy tales, particularly epic fantasy; central hero, war and military virtues, colorful and dramatic yarns, large-scale action and stakes. The trappings are still different in space opera, with stories set in the far future, and the use of space travel and so forth. But what about that optimism? It’s an interesting stand out, as is the tendency toward an adventure narrative. Epic fantasy can end happily and be adventurous at times, but it often doesn’t read with a plethora of either of those traits. The Lord of the Rings is harrowing. A Song of Ice and Fire is full of trauma and darkness. The Wheel of Time turns on minute detail and precise depictions of a world that has been thought through in every aspect. Fantasy lends itself to extreme specificity and worlds in turmoil—space opera doesn’t have to in order to work.

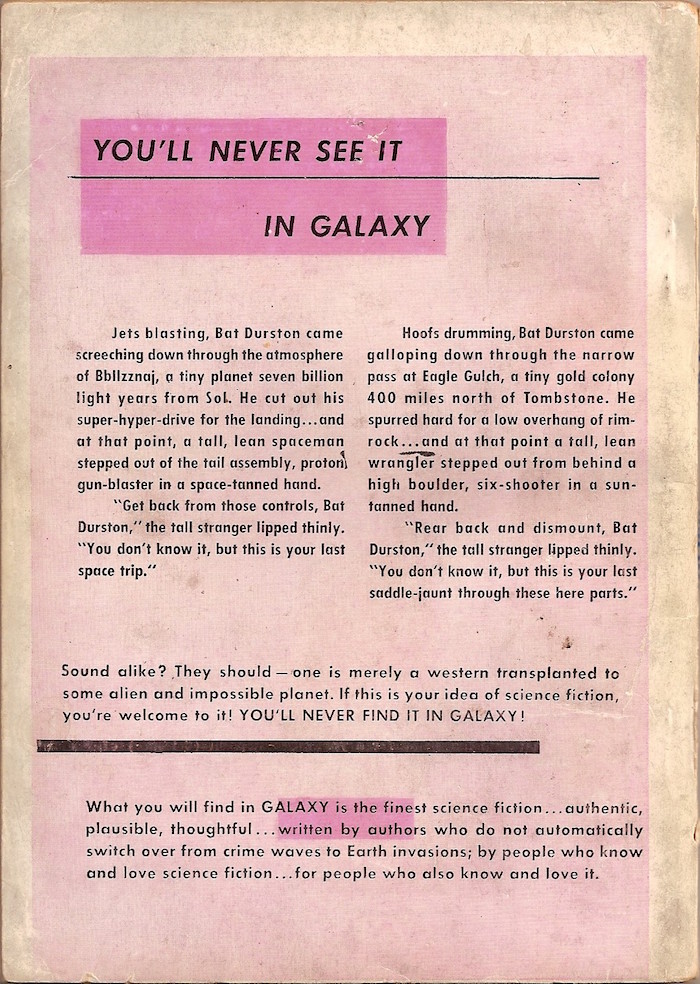

What’s more fascinating is that the comparison to fantasy is relatively new in the history of space opera’s existence as a genre. In fact, what it used to be compared to was the “horse opera”… that is, Westerns. Here is the back cover of the first issue of Galaxy Science Fiction from 1950:

Whoa. Outside the fact that this copy is throwing some serious shade, we can glean a better sense of what space opera meant to many seven decades ago, and how it was viewed. And what it reveals is perhaps a larger problem: why has space opera always been compared to other genres throughout its history? Why can’t it just be considered its own thing?

The macrocosm answer is simple enough: stories are stories. They all rely on similar devices, tropes, and narrative styles. There is very little that sets one genre apart from another in the broadest sense, and that’s perfectly fine. The microcosm answer is more complex: space opera used to be an insult, and it has taken years and the advent of incredibly successful space operas—like Star Wars and the Vorkosigan Saga and the Culture series—to allow it to stand on its own. But perhaps all those years of hanging out in the shadows has made fans more hesitant in parsing out what they love about the genre.

So what is it?

As a fan of the genre, I find the Western comparison hilarious because Westerns are very much not my thing. So what makes the difference? Why are aliens and robots important? Why are ray guns and space travel better than horses and six-shooters? There’s a part of me that wants to argue for introspection in that vein; robots and aliens are often used as a way to examine aspects of human nature, to dissect ourselves by using other beings as a template. Dwarves and orcs can do this too, but seem a bit more earth-bound, whereas robots and aliens are a part of our future—they ask questions about where we might go, what challenges we might face as we evolve.

But there’s also the “opera” part of space opera, something that doesn’t get enough credit in the phrase. After all, labeling something an opera creates a very specific expectation in the mind of your audience. It grants your story scale, yes, but not just in terms of set pieces and costumes. Opera is all about performance, about emotion. Operatic stories are bursting with feelings that can only be spelled out in all-caps. You don’t need a translation of an opera to understand it because the spectacle of it should transcend the need. Opera works with visuals, music, dance, poetry, as many forms of art as we can shove into a collective space and time. Opera is bigger than all of us.

Space operas often deliver on those terms. They are writ large and bursting with color and light. Perhaps that is the distinction worth making in the quest to explain its pull as a genre. Taking the opera out of space opera leaves us with… space. Which is great! But I don’t want to spend most of my musings on space marveling at the use of silence in Gravity. Space needs a little melodrama. It needs an opera.

Is space opera just fantasy in space? To each their own on that definition. But there’s a difference between the two all the same, and even if we don’t need to pin it down, we can at least honor the fact that space opera is no longer an insult—it encompasses many of the stories that we treasure.

Originally published in May 2017.

Emmet Asher-Perrin has been asking for a robot friend and an alien friend since childhood. You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.

You know, I never really looked into it academically, but I always thought of “space opera” as being, in large part, about the relationships. I LOVE robots, spaceships, laser battles, aliens and all of it. But the memorable parts, the things that linger, for me, are the relationships. In Star Wars, Farscape, Firefly, and even, might I suggest, X-Files the things we remember are the characters and how their interactions make us care about them. Something like Ringworld, usually considered “Hard Sci-fi” is mostly about one protagonist dealing with an adverse environment and situation. Relationships are far less central. That’s always how I’ve seen it anyway, opera = relationships.

Also, thanks for another fantastic essay. This was yet another article where I started reading and thought, wait, this author is right in sync with my thought process and ethos, it must be Emily. And I checked and it was!

Strange no mention or reference to the Grandaddy of modern space operas, Star Trek…. which was pitched as ” Wagon Train To The Stars” …. after a western yet.

I just wish Amazon would stop shoving Military SciFi in the Space Opera category. Those two things may have the same settings and even characters, but they are wildly different kinds of STORIES.

I’m inclined to see it as its own thing as well, big enough to merit being its own subgenre alongside science fiction and space fantasy (they’re all under the general genre of “speculative fiction”, and “space opera” probably tells you as much about a potential story as calling it “science fiction” does).

All that said, it does overlap pretty heavily with space fantasy and science fiction, with the key distinction being this between the two:

I would speculate that part of the divide is that while there are those of us who fall within the overlapping set of the venn diagram of Fantasy, Science Fiction, and Space Opera (especially on this site, which deals with all speculative genres), the vast majority of genre readers thirty years ago fell outside the overlap. To the typical hard SF reader, Space Opera is silly.

Until very recently, most people bought books by walking into a bookstore and browsing the shelves, and consumed short stories through subscriptions to magazines. And as a Tor employee once told me, as far as bookstores are concerned, “If it has a space ship on the cover, its Science Fiction.”

So, you have the larger subset of SF readers who go to the bookstore and can’t tell the difference between what is Space Opera and what is their beloved hard SF. The descriptions aren’t always helpful, either. They drop $50 on a number of books, get home, start reading something, and feel betrayed. Or their SF magazine comes in the mail, that they pay for quarterly, or monthly, and half the stories are not what they’re looking for. So, space opera becomes the ghetto within the ghetto. Until Trek, and Star Wars, and the rise of Epic Fantasy bring the genre to more people. And Space Opera is far closer to other kinds of adventure stories and movies that the casual genre fan may also be interested in. So, there’s something of a flip happening.

Space opera has NEVER been “fantasy in space”. It’s a subgenre of science fiction, not of fantasy. Although, watching Star Wars, I can see how people would get confused about this. It has always been possible to interpret Star Wars equally well as either sci-fi or fantasy (at least until the latest movie, which no longer pretends to be sci-fi, but is pure fantasy), but anything that takes place in space and uses spaceships and other sci-fi tropes MUST BE SCI-FI. To mix it up with fantasy elements can only work to its detriment, in my opinion. But I guess I am something of a science fiction purist (who uses the terms “sci-fi” and “science fiction” interchangeably, by the way).

What in the name of Frak and the Colony of Kobol is Starbuck looking at?

Space operas often feature telepathy (magic), FTL travel (teleportation), monstrously implausible battles (which have more to do with Trafalgar or the Pelennor Fields than actual science) and laser bolts (fireballs). More to the point, those “space operas” which go out of their way to avoid these tropes and invoke actual science – like say Alastair Reynolds’ Revelation Space series – are re-labelled “hard SF” instead.

Many of the most famous works of space opera have strong parallels with fantasy or other genres: Dune, Babylon 5, Star Wars, Warhammer 40,000, some elements of Star Trek, David Weber’s work etc are all rooted in fantasy or history, not in actual science fiction.

So yes, I feel quite comfortable agreeing with George R.R. Martin’s “Furniture Rules”, at least in the main. Space opera very often is fantasy. It’s nice when it isn’t, but when it isn’t, it’s no longer labelled space opera. QED.

@8:

In general, I agree with you, as long as you are willing to limit the definition of “actual science” to the hard sciences. Especially physics. There is plenty of science in Dune for example. Most of it is social science, however, with a smattering of ecology. Same for the Vorkosigan Saga. And there are plenty of physicists who would argue that creating a stable Einstein-Rosenberg Bridge is an engineering problem, not a physics problem. So FTL via wormhole hasn’t been the realm of “soft” science fiction for about 25 years now. Maybe longer.

As noted by @5 Anthony Pero, named genres exist largely as a way to organize physical bookstores, which is done to cater to buyers’ tastes. “If you liked one book under this heading, you may like others” (although you may also like books found in other sections). In isolation, it’s never going to be a perfect recommendation — by analogy, imagine if restaurants were classified by their principal ingredients. “I find that I liked this place called ‘Noodles, with Tomato Sauce in Italian Style.’ Will I like ‘Noodles, with Fish Sauce in Vietnamese Style?’ Egads! The spices are completely different!” Conversely, imagine a bookstore with a single “fiction” section organized exclusively by author — wouldn’t that be frustrating?

Now, an electronic bookstore needn’t be constrained by the tyranny of physical space (“file each book in exactly one category”), but as noted in @3, Amazon’s taxonomy doesn’t necessarily serve, either. OTOH, you have something like Netflix, where the categories are an emergent property of what viewers seem to like, rather than being assigned by a human cataloger with preconceptions.

One can posit an AI recommendation engine that, like a well-read bookstore clerk, can detect the properties of a story (length, text stylings, number of characters, presence of tropes) and can quiz you on your preferences — but this won’t help if the reader himself can’t articulate why he liked one story and not another.

I’ve read enough “hard science fiction” that has become completely obsolete to realize that what we call “hard” is just as fantastical as Star Wars –it’s just based on the fantasy conceit that there are no new discoveries or technologies to come, that in hundreds of years, everything we have will still be built to today’s best-hope specifications. There are no smartphones in the future. I’m fine with artificial gravity, directed-energy weapons, FTL, aliens, and even time-travel, if it can be at least dressed up in plausible science.

I still think the more useful distinction is between Space Opera and Space Western: where space opera is concerned with larger-than-life matters of cosmic significance, space westerns are about the common, everyday folk who just happen to be living and working in space.

Characters in a space opera are often (but not always) beings of importance, with uniforms and titles, and associated with powerful entities –nations, corporations, navies, or religions. They never have to worry about their paycheques or where their next meal is coming from, and so are free to explore strange new worlds and debate philosophy over wine.

Characters in a space western are more rugged, usually freighter crews, smugglers, pirates, or rank-and-file military grunts (who fight the wars that those fancier people start and end). The powerful forces around them aren’t active agents, but obstacles or forces of nature to be avoided or accepted, while their real focus is just staying alive and putting food on the table however they can.

The details of the setting are in service to this; if space is easily traveled, full of civilized nations, expect a space opera crew to navigate treacherous politics. If space is an unsettled wilderness full of navigational dangers and dangerous “natives,” expect a space western crew to flee there to escape from the Law.

(Star Wars, at its best, is a collision of worlds, between Leia’s space opera story of the Rebel Alliance against the Empire, and Han’s space western story of smugglers and crime lords –both of them witnessing the Jedi from different perspectives, whether iconic war-heroes or hokey religion.)

He just heard that Katee Sackoff landed his part in the BSG reboot…

Which, BTW, is probably the most glorious example of space opera to ever grace the small screen.

i think the distinguishing point from Space Opera and Fantasy is the old term “Sense of Wonder”.

Also, about the Western roots of space opera, it depends: they are stronger when dealing with the myth of “the Frontier” (that any realistic SF nowaday must realize it will be never found in those terms in space, and would be ethically questionabile even in case we found it nothwithstanding probabilities).

But injecting an adequate dose of Sense of Wonder, you can also have “napoleonic wars in space”, “colonial narratives a-la Kipling in space”, “pirates stories in space”, “rise and fall of the roman epmpire in space”, “detective stories in space”, and all that…

Cybersnark@11:

That definitely falls firmly into the physics vs engineering problem I referenced @9. Hard science fiction does its best to extrapolate what future technologies might be engineered while remaining within the guidelines of our current understanding of physics. And the underlying principles beneath modern physics have been around for almost 100 years now. Our understanding of the physics of sub-atomic particles has changed greatly in the past 50 years, and is still evolving, but not the basics of astrophysics. So, while the imagination of Hard SF writers of the Golden Age may have been outstripped by modern engineering, the underlying physics shouldn’t have changed.

And Space Opera was never concerned with physics. Its using the SF setting to illuminate character, and other story telling dynamics.

I would argue that what makes something a Space Opera, or a Space Western, or MilSF or Hard SF has more to do with what drives the story than anything else. Space Opera and Space Westerns fall within the same general category of stories. They are concerned with individuals or individual groups, and how characters grow and change due to what happens. While the “types” of people are different, as you point out, between a Space Opera and a Space Western, the stories use the same structure, and many of the same archetypes.

Military SF, on the other hand, has the same trappings as Space Opera. Interplanetary wars, Emperors and Generals and men and women in uniform, etc. But they have very, very different story structures. Whereas pure Space Opera involves war and politics and civilizations on grand scale, its concerned primarily about individual characters and their journeys. That’s what drives the story forward. Military SF is inverted. It involves individual characters and their journeys, but is primarily concerned with war, politics and civilizations. These larger movements are what move the story forward.

With Hard SF, the story will involve many of these other elements, but will not be primarily concerned with them. What tends to drive the story forward is the scientific discoveries of its characters. That’s why so many of them are Idea or Milieu stories, to borrow from Orson Scott Card’s MICE Quotient.

That’s why Space Opera does compare more to Epic Fantasy. Its not the wishy washy science. Its the focus on character and individual driven plots. They are the same type of story.

Now, obviously, these aren’t hard and fast rules. There are overlapping sets with genres, just like with readers. On the Space Opera side, The Expanse is so popular primarily because it sits firmly within an overlapping set that includes Hard SF, Military SF and Space Opera. Dune ticks multiple boxes as well. On the fantasy side, Malazan manages to be an epic fantasy that is primarily about the larger picture, while still telling some character driven stories.

Opera is about people and their emotional relationships — love, jealousy, hate, betrayal, loss — Rigoletto is about love and jealousy. Madame Butterfly is about love, loss and betrayal, Don Giovanni is about lust and the misuse of power, etc. Soap opera was called “soap opera” because it is essentially opera minus the music and singing, plus soap commercials. The appeal is the same — people dealing with intensely emotional situations. Opera is the stuff of which crying in your beer C&W songs are made.

It’s the “opera” part that defines space opera to me. The “space” part is the stage set — rather than set in the past or present, it’s set in the future.

Hard SF deals with things — events, causes and effects, concepts and ideas. Space opera deals with people and their relationships and how outside events and situations effect them.

To me, it’s about point of view. You can take an event or series of events, what caused the event(s) to happen, and the aftermath and view it from several different angles.

Hard SF is “this is what happened, this is why it happened, this is how it happened.” Space opera is “this is what the people who had to go through what happened felt about it happening, and how they came to terms with what happened and dealt with the aftermath.”

Yeah, the Vorkosigan saga deals with big sweeping events and massive battles and such like, but the focus of the stories is on the main characters. –Cordelia, Aral, Miles, etc. — and how they interact with each other emotionally and how the events of the stories affect those interactions. Same for the Liaden stories (Lee and Miller), the Foreigner stories (Cherryh) and other such “space operas.”

er, make that “Rigoletto is about power, its abuse and revenge. Pagliacci is about love and jealousy.

” Westerns are very much not my thing.” You just made me cry. :(

@2 – Brian: The “Wagon Train to The Stars” in the Star Trek pitch is not because they’re saying they’ll make a space western (TOS is not that), but because the original idea for the show was to have it be about the guest stars of the week, with the regular cast/crew of the starship Enterprise as a backdrop; just like the show “Wagon Train” was. Of course, it didn’t fully coalesce into that, as the Trek characters grew popular, but that was the plan.

So this…

Space Opera!

I stopped trying to classify the stories I enjoy into little niches… When forced, I go by three broad categories. Fantasy (historical setting or made up quasi historical setting); Modern (contemporary events, recent past to near future setting); Sci-Fi (stories based in, around or adjacent to either interstellar travel or (quasi-)scientific concepts). In general I just call them ‘stories’ though.

I wish fantasy and space ANYTHING would quit being lumped together. I also wish there were more budding space exploration novels with humans just leaving earth. It feels like there was suddenly world’s settled everywhere without all tthe stories of discovery and learning and living that would be in between.