Studio Ghibli is known for making coming-of-age films, and for films with complex female characters, but there are two in particular, made 6 years apart, exemplify these traits better than any of their other work. One is considered an all-time classic, while the other is a lesser known gem. One gives us an alternate world full of magic and flight, while the other stays purely grounded in this world. But taken together, Kiki’s Delivery Service and Whisper of the Heart celebrate the single-minded passion of the artist, and the need for young women especially to ignore societal pressures in order to create their own destinies.

Historical Background

Kiki began life as a children’s book written by Eiko Kadono, a much simpler, picaresque adventure story compared to the film, which stresses Kiki’s emotional growth and existential crises. When Miyazaki chose to adapt it he also added Kiki’s struggles with her loss of magic, and then wrote a dramatic blimp accident to supply the film’s climax. Trust Miyazaki to find a way to stick an airship into a story about witches…

When Kadono wrote the story, she titled Kiki’s service “takkyubin” which literally means “express home delivery” or “door-to-door service”. This phrase had been used and popularized by the Yamato Transport Company—whose logo, a mother cat carrying her kitten, bears a resemblance to Kiki’s familiar, Jiji. Yamato’s logo is so popular that the company is often colloquially called “kuroneko” – black cat. Miyazaki’s partner Isao Takahata approached the company when they began the adaptation, and the transport company eventually agreed to co-sponsor the movie, thus smoothing over any copyright worries.

Kiki was a big hit, and was the highest-grossing movie movie at the Japanese box office in 1989—the film’s success inspired Kadono to write a series of sequels to Kiki’s original adventure. It was also one of the first Ghibli films available in the US, when Disney released an English-language dub on VHS in 1998. (And, if you’d like to read a completely obsolete sentence, according to Wikipedia: “Disney’s VHS release became the 8th-most-rented title at Blockbuster stores during its first week of availability.”) The dub featured Kirsten Dunst as Kiki, Janeane Garofalo as Ursula, and the late Phil Hartman as the acerbic Jiji—a prominent cast for a fairly early foray into Disney’s attempts at marketing anime.

Whisper of the Heart was based on a manga by Aoi Hiiragi. The film, released in 1995, was the directorial debut of Yoshifumi Kondo, a veteran Ghibli animator (including on Kiki’s Delivery Service), who was seen as the obvious heir to Miyazaki. The film was a success, and two years later, following the blockbuster of Mononoke Hime, Miyazaki announced his retirement, seemingly with the idea that Kondo would become the studio’s primary director, while Takahata would continue turning out masterpieces at his slower rate. But, as Helen McCarthy’s history of Studio Ghibli relates, mere days after Miyazaki’s farewell party, Kondo died suddenly of an Aortic dissection. This obviously threw the studio into disarray, and led to Miyazaki coming back to work, but at a much slower pace, as many in the industry felt that Kondo’s tragic death was a result of overwork. With his one directorial effort, Kondo proved that he was a delicate, sensitive craftsman with an eye for the tiny details that imbue every day life with magic.

Whisper of the Heart was a hit in Japan, earning 1.85 billion yen, and garnering strong reviews. But it didn’t get anywhere near the traction in the US that some of Ghibli’s other films did. It’s about kids in mid-90s Tokyo, with very little of the fantastical element that people had already come to expect from Ghibli, and it’s also a deceptively simple story, as I’ll discuss below.

Kiki’s Delivery Service

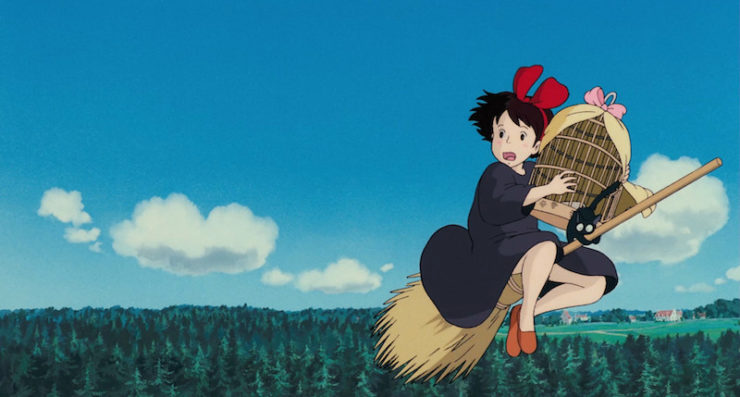

Kiki is a young witch, and since she’s turning 13, it’s time for her to follow the witch tradition of setting out on her own and establishing herself in a witchless town. She leaves her mother and father and flies toward the sea—but since this is Ghibli the burst of freedom is tempered by responsibility. Kiki can only take her cat, Jiji, with her, and she has to dress in a regimented black dress so everyone will know she’s a witch. From now on her own desires have to take a backseat to the needs of her town, as she’s essentially a public servant.

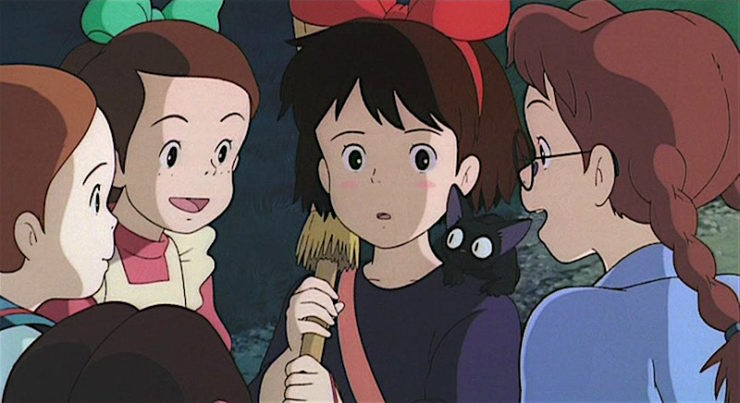

She finds an idyllic city near the sea, establishes that they don’t have a witch already, and lands on the street to take stock. She immediately attracts the attention of a group of young girls of the town, who look at her like an odd zoo animal—her freedom is inextricably bound to her otherness.

In short order she finds a homey bakery in need of a delivery girl, and agrees to exchange her work for an apartment behind the shop. The bakery’s sales go up once they start advertising their magical broom-based delivery service, and Kiki gains a new set of parental figures in Osono and Fukuo, the husband-and-wife bakers—but they’re also her employers. They check on her when she’s sick, and encourage her to take time off, but they also expect her to work hard, and they treat her as a young adult rather than a little girl.

She does make one friend her own age: a boy named Tombo. Tombo resembles a younger version of Kiki’s dad, and he’s awkward and nerdy and completely enamored of her witchiness, just as her father seemed to have been enraptured by her mother years before. Tombo loves flight, and part of his interest in Kiki is sparked by seeing how much she loves it, too. The tentative friendship turns on their conversations about flying, with Kiki supporting Tombo’s ridiculous attempts to build flying machines, but since her confidence has taken a hit since she left home, she’s also apt to run away when she’s faced with Tombo’s friends. It’s just too much to take.

Kiki’s Delivery Service becomes a success, but it also means that Kiki can’t practice any other witch skills. (I could say something about how even in a children’s fantasy movie the realities of capitalism constrain magic…but that’s a whole other article.) This radiates through the film in a surprising way. During a delivery, Kiki is attacked by birds and drops the toy she’s carrying to a country manor.

She finds it in a cabin, but more importantly she meets an artist named Ursula, who kindly fixes the damaged toy, allowing Kiki to finish her job. A few weeks later she’s commissioned to deliver a fish pie to an elderly lady’s granddaughter, but has a rough flight. Soaked and bedraggled, she learns that the pie is for one of the snotty girls who gawked at her on her first day in the city. The girl is dismissive toward both Kiki and the pie, and haughtily sends the girl back into the storm. For a moment Kiki has a glimpse of the life other girls her age are living: birthday parties, time with friends and family, pretty clothes and gifts. Between her depression and the chilling weather, she ends up with a fever…but far worse, she has a crisis of confidence that robs her of her ability to fly, her broom breaks in a crash, and maybe worst of all she realizes that she can no longer understand Jiji.

She has no other talents to fall back on. She’s never learned potions or healing magic or divination. So the witch ends up as a shopgirl, answering phones for Osono, knowing that she’s not really earning her keep, with no idea whether she’ll ever get her powers back. Will she have to go home in disgrace? Is she even a real witch?

Luckily Ursula shows up.

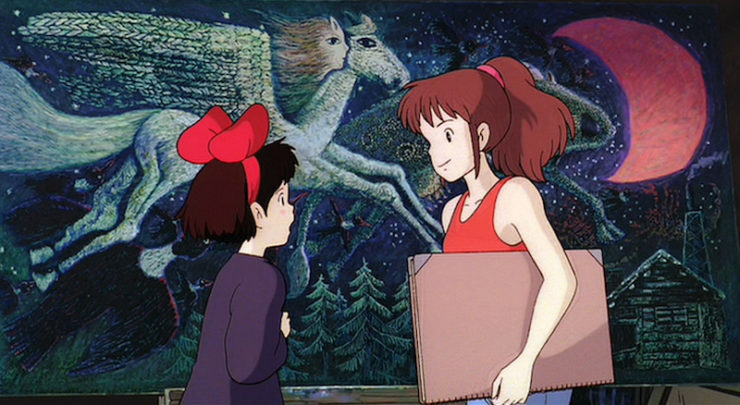

The older woman recognizes the thousand-yard-stare of an artist who has lost her way, and chooses to do the generous thing: she invites Kiki to take a damn vacation already and come back to the cabin with her. For me, this is the heart of the film. Ursula removes Kiki from her ordinary life to give her a new perspective, the two women discuss the similarities of art and magic, and for the first time the young witch is able to see her life from a distance. The next day Ursula reveals her work in progress, and Kiki realizes that she’s inspired her friend to create a beautiful work of art:

Seeing herself through her friend’s eyes makes her realize that she’s more than just the town witch.

She visits Madame, her elderly friend, who makes her a version of the pie that her jerk granddaughter rejected. And then a crisis hits: Tombo is involved in that zeppelin crash that I mentioned earlier. Kiki rushes to help, borrows a streetsweeper’s broom, and rescues him. The film ends with Kiki able to fly again and restarting her delivery service, but more importantly, it ends with her knowledge that she’s a whole person, not just a function. Her magic is an art that will grow with her. Best of all she knows she’s not alone. She’s part of Tombo’s group, she’s part of Osono’s family, she has Ursula, Madame, and Madame’s maid—adulthood doesn’t mean going it alone without her parents, it means building a new community. Plus Jiji has started a family with the cat next door.

Whisper of the Heart

I’ll begin by saying that Whisper of the Heart, while one of my favorite-ever Ghibli film, features more renditions of John Denver’s 1971 hit “Take Me Home, Country Roads” than any film should have—including a cover by Olivia Newton-John. The movie opens over Tokyo—bustling sidewalks, commuter trains, office windows still lit long into the night. We join our heroine Shizuku as she steps out of the corner market, dodges neighborhood traffic, and finally steps into her family’s tiny, cluttered Tokyo apartment. Her father works at the family’s computer in the one large room, as her mother works on a paper at the dining table. The room is dilapidated, dishes piling next to the sink, books and papers sliding from shelves. Shizuku’s older sister, a college student, also lives at home.

The details build gradually—the washing machine is in the shower room, separated from the main room by a curtain. The two sisters have bunk beds, each with their own lamp and a curtain, so they can essentially retreat into their own space and block some of the light and sound out. We never see the parents’ room, because the girls have no reason to go in there, but I think it’s safe to assume that it is as Spartan-yet-cluttered as the rest of the house.

We’ve met Shizuku at a crossroads in her life: she’s in the waning days of her summer vacation, and when school resumes, she’ll be taking her high school entrance exams. These exams will determine her future, and it’s all anyone at school talks about. Things are changing at home too—father is a librarian at the large county library, and they’re switching from card catalogues to digital records (father and daughter agree that this is not a good change); mother has started classes at the local university, with plans to start a new career after graduation, which has required Shizuku and her sister to help with the housework; older sister is juggling college and part-time work, and planning to move out on her own. Shizuku is trying to hold onto the last scraps of her childhood—sleeping in, reading fairytales—as her family tries to push her into adult responsibility and her friends try to push her into romance. The plot is whisper thin, but also not the point.

Shizuku notices that each time she check out a book for her project, the name Seiji Amasawa appears on the card above hers. She starts researching the Amasawa family to try to learn more about this mystery reader. Later, she sees a cat on the train, follows it at random, and discovers an antique shop run by a loving elderly caretaker who just happens to be Seiji Amsawa’s grandfather. Shizuku visits the store and becomes entranced by a particular antique, a cat figurine called The Baron.

She spends time with Seiji while struggling to keep up with her studies, and the film seems to be a sweet YA anime. But the whole film shifts abruptly when Seiji announces he’s going to Cremona, Italy to learn to make violins. This doesn’t happen until about the 45-minute mark, but suddenly the story snaps into focus: talking with her best friend Yuuko, Shizuku realizes that what she really wants is to write a story like the ones she loves. She decides to spend the two months that Seiji is gone testing herself by writing an entire short story. Seiji’s grandfather agrees to let her use the Baron as her main character, on the condition that he gets to be the first person to read the story.

It becomes extremely clear that Kondo has been lulling us with a comfortable coming-of-age movie for nearly an hour, when he was actually creating the origin story of an artist. We’ve been passively watching Shizuku’s ordinary life, just as she was content to read for hours at a time, but now she is actively challenging herself. She spends hours in the library doing research for her story, and we get to see snippets of it—a lovely fantasy of a cat who must rescue his lover with the help of a young girl and a magical jewel. We see traces of stories like Peter Pan and Pinocchio, but also some moments of real originality.

Her grades fall, her sister freaks out, her parents worry, and she doesn’t sleep much, but she meets her deadline. As promised, she shows the finished story to Grandfather Nishi, before having a slight breakdown from all the stress. And then she returns to normal life, but it’s clear that she’s a changed girl. She treats her romance with Seiji as the beginning of an artistic partnership. and makes it clear she plans to make her own way in the world. Even her decision to recommit to school is framed as an artistic choice, when she says she needs college in order to become a better writer.

The Perfect Pairing

So last time on the Ghibli Rewatch, I talked about how watching My Neighbor Totoro and Grave of the Fireflies together was not exactly a fun experience. I’m happy to report that Kiki and Shizuku make for a perfect pair. In fact, if I had access to a daughter and her friends? I would suggest that this is the best slumber movie marathon ever created by human hands. There are two elements that I think make these among the most important of Ghibli’s movies…

The Power of Female Friendship!

Whisper of the Heart is slightly weaker on this. Shizuku has a tight-knit group of friends who are supportive of her artistic tendencies, including encouraging her English to Japanese translation of “Take Me Home, Country Roads”, but they’re not in the film that often. While I personally find Shizuku’s sister insufferable, she is trying to be helpful, and thinks that bullying her kid sis into better grades and more chores will make her stronger. I don’t agree with her methods, but I do think her heart is in the right place. The other two women in Shizuku’s life are more significant. Shizuku’s mother mostly leaves her daughter alone to work (which is probably as much a result of the mom’s own studies as any attempt to encourage independence) but when Shizuku faces her parents and tells them of her need to test herself with her writing project (more on the below), her mother doesn’t just tell her to go ahead and try—she also goes out of her way to tell Shizuku that she, too, has had times when she needed to test herself against deadlines and challenges. She makes herself, and her hard work and sacrifice, a model for her daughter to follow. And then she nudges the girl and tells her she still has to come to dinner with the family. Finally we come to Shizuku’s best friend, Yuuko. Yuuko doesn’t have a terribly large role, but her friendship is pivotal. Shizuko first decides to test her writing through a conversation with Yuuko, not Seiji. It would have been easy for the film to give Seiji that scene, since he’s the other character with a real artistic passion. Instead the film shows us the more emotionally resonant path of placing that decision in a conversation between two best girlfriends.

This theme is much stronger in Kiki. The generosity of all the characters is incredibly touching. Kiki is part of a matrilineal line of witches. When she leaves the safety of her mother, she is taken in by Osono, and befriended by Ursula, Madame, and Madame’s maid. She does have to deal with a few mean girls, but Tombo’s female friends actually seem cool—it’s Kiki who freaks out and runs away from them, but by the end of the film it’s clear that they’re completely accepting of her. The film subtly shows us different phases of a woman’s life, all presented to Kiki as potential choices: she meets a snooty witch, and then a group of girls who represent the typical teenager girlhood she’s leaving behind for a life of witchery; Osono is hugely pregnant, so Kiki also gets an immediate, non-parental model of marriage and new motherhood; Madame provides an example of loving, dignified old age.

Best of all, though, is Ursula. Ursula is a young painter, in her early 20s, working to make it as an artist. She lives alone in a cabin, and is entirely, gloriously self-sufficient. She gives no fucks about social mores, feminine beauty standards, corporate ladders—all that matters to her is her art. When she sees that Kiki needs her she steps into a mentorship role, with no expectation of reward beyond a sketching session.

She is perfect.

The Life of the Artist

I will admit that there was a time in my life (college) when I watched Kiki at least once a week. I didn’t really have the time to spare, but I felt so adrift and unsure of what I wanted to do with myself that losing myself in Kiki’s story of failure and rebirth became my own sort of reset button. Each week I’d watch this girl prove herself, fall and get back up. I watched it in the hope that the story would rewrite my own synapses, make it possible that failure was a temporary condition, that I, too, would get my magic back. While Mononoke Hime was my first Ghibli film, and Porco Rosso my favorite, I think Kiki was the most important to me. It’s so rare to see a story of an artist in which failure is treated as natural, inevitable, and part of the process. Of course her magic fails—she’s killing herself with too much responsibility, and she isn’t allowing herself to enjoy flight anymore. When flying stops being fun, you need to take a break and reevaluate.

It’s a perfect metaphor, and the fact that Ursula is the one who steps in to help just makes it all the more resonant. No matter what art or craft you practice, you have to refill your tank occasionally.

Where Kiki has adulthood thrust upon her at the age of 13, Shizuko actively chooses to try living as an adult, full-time writer for two months, to see if she can produce a real story like the ones she loves reading. No one would blame her if she gave up and lived as a regular student for a few more years before heading off to college—her family would actually prefer it. And she isn’t doing it to impress Seiji, as he isn’t even there to see how hard she’s working, and at that point she thinks he’s staying in Italy for several more years. This is purely for her—to test her own mind and resolve against a blank page.

The film goes from being a fun piece of YA to a great look at the artistic life by treating this completely realistically. Shizuku doesn’t just sit and scribble words down—she goes to the library repeatedly to do serious research for her story, which is the thing ironically that finally gets her to focus rather than passively reading storybooks constantly. She pours herself into her work with a dedication that is far beyond her work on exams, and has stacks of books around her so she can cross-reference. We see her re-reading, editing, swapping words out. She’s trying to craft a real, publishable story. You don’t get to sit down and manically write your way through a montage that ends with a perfect, polished story that magically flies through the New Yorker’s slushpile. You stay up late, you get up early, you drink an unhealthy amount of coffee, you hear a lot of voices (all of them louder than the whisper of your heart, and many of them your own) telling you your project is foolish, and at the end of the whole process you collapse in tears from stress and exhaustion as one person tells you the story’s pretty cool. (And hell, Shizuku’s lucky—at least one person liked the story. Plenty of people write stories for years before anyone likes them…)

The film doesn’t sugarcoat the difficulty of the creative process, and it also doesn’t try to turn Shizuku into a cute kid who’s doing her best. She wants the story to be great, and she falls short of her own standards: “I forced myself to write it, but I was so scared!” When Grandfather Nishi tells her he likes her story, he also tells her “you can’t expect perfection when you’re just starting” and makes it clear that this isn’t a masterpiece, it’s only a beginning. Writing, like all endeavors, requires work and practice. It requires failure. Most adult films about writers never capture this kind of work, so seeing it here made me ecstatic.

Maybe the absolute best part of all, though? Once her parents notice her obsession they sit down and talk with her, seriously, about why she’s pursuing writing. In what may be my favorite-ever Ghibli moment they tell her to go ahead with it. Her father says, “There’s more than one way to live your life,” but follows up by saying that she’ll need to live with the consequences if her writing project tanks her chances of going to a top high school. And as she learns in working on the story, she’s going to need proper research skills and strong discipline to make it as a professional writer, so she’s going to have to be serious about studying. After Grandfather Nishi reads her first story the two eat ramen together and he shares a little of his life story. She goes home and tells her mother that she’s going back to being a regular student…at least for now. And even when the film ties the romantic plot together, and makes it clear that she and Seiji are going to embark on a romance, both of them frame it as a creative partnership rather than just two kids dating.

These two films are so good at showing what it means to try to follow a creative path in life—whether it’s writing or painting or craft beer brewing or hairstyling. Any time you try to express yourself creatively there is going to be an undercurrent of terror that people might not get it, might reject you, might mock you. Your work might not live up to your own standards. But Studio Ghibli was brave enough to give us two films, neaarly a decade apart, assuring young girls that failure was just part of growing up, and that when you found something you were truly passionate about, you should pursue it with your whole being.