Summer of Sleaze is 2014’s turbo-charged trash safari where Will Errickson of Too Much Horror Fiction and Grady Hendrix of The Great Stephen King Reread plunge into the bowels of vintage paperback horror fiction, unearthing treasures and trauma in equal measure.

“Last night I cast my first spell…this is real power!” Debbie gloats.

“Which spell did you cast, Debbie?” Ms. Frost asks.

“I used the mind bondage spell on my father. He was trying to stop me from playing D&D…He just bought me $200 worth of new D&D figures and manuals. It was great!”

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to 1984, the year Jack Chick published his famous anti-RPG tract, Dark Dungeons, revealing the shocking truth behind D&D: it is a gateway to Satanism and suicide! If you have rolled the polyhedral die, the only way to save your immortal soul is to burn all your monster manuals and player handbooks for Jesus. Underneath all its bluster, the moral lather B.A.D.D. (Bothered About Dungeons and Dragons) worked itself into over RPGs had a very real nougaty center: the very sad suicide of a child prodigy named James Dallas Egbert III.

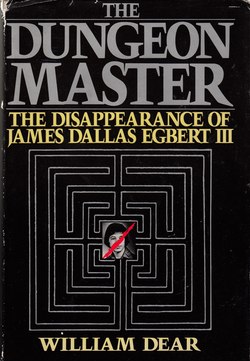

Three very naughty people were at the center of the exploitation of Egbert’s suicide: Rona Jaffe, John Coyne, and William Dear. First, the actual facts of the case. In 1979, Egbert disappeared from his dorm room at Michigan State University and was traced to the steam tunnels that ran underneath the campus. There the trail went cold. His parents hired private investigator and tireless self-promoter, William Dear, to look into the case. Dear knew that Egbert played D&D, and he knew that some of the Michigan State students LARP-ed in the steam tunnels, and he knew absolutely nothing about D&D, so he mused to a reporter that D&D might have had something to do with the disappearance. That was all the press needed to hear to declare that Egbert had died in a D&D game “gone wrong.”

If you’ve played D&D you know that a game “goes wrong” when someone throws a hissy over a roll, or one player keeps screwing around on his cell phone and ignoring what’s being said. And if you’ve never played D&D you assume that when a game “goes wrong” Satan is summoned and sucks out everyone’s soul. By the time Egbert showed up six months later, living in Louisiana under an assumed name, William Dear’s far more colorful version of events had taken hold in the media consciousness and two books were already on their way to market.

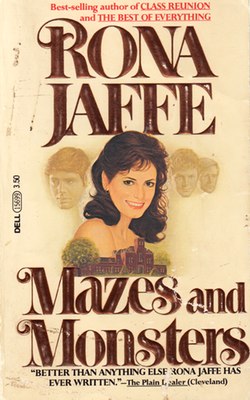

The first was from Rona Jaffe, extremely famous author behind the scandalicious bestselling proto-Mad Men and proto-Sex and the City novel, The Best of Everything. Published in 1958, TBoE provided not only a great late-career role for Joan Crawford in the inevitable movie, but it also provided deep insight into what it was like to be a young woman in 1958. Mazes and Monsters, on the other hand, provides no insight into what it was like to be a D&D player in 1980. It’s a book written by an author who knows nothing, and cares less, about roleplaying games, only coming to life when she devotes her time to the backstories of the RPG enthusiasts’ parents, each of whom was a young person in 1958.

The first was from Rona Jaffe, extremely famous author behind the scandalicious bestselling proto-Mad Men and proto-Sex and the City novel, The Best of Everything. Published in 1958, TBoE provided not only a great late-career role for Joan Crawford in the inevitable movie, but it also provided deep insight into what it was like to be a young woman in 1958. Mazes and Monsters, on the other hand, provides no insight into what it was like to be a D&D player in 1980. It’s a book written by an author who knows nothing, and cares less, about roleplaying games, only coming to life when she devotes her time to the backstories of the RPG enthusiasts’ parents, each of whom was a young person in 1958.

She does mint two conventions that became staples of this mini-genre, however. The first is that each of the kids turned to RPGs because something was broken inside of them (Kate’s parents are divorced; Daniel’s parents push him too hard; Jay Jay is neglected by his divorced parents; and Robbie’s brother ran away from home). The other convention is that her role-playing system is very silly. (“Kate was Glacia, the fighter, Jay Jay was Freelik the Frenetic of Glossamir, a Sprite, and Robbie was Pardieu, a Holy Man.”) Daniel, of course, is the Maze Controller. As Kirkus sighs, “Jaffe never succeeds in making this obsession (or the boring game itself) credible.” Mazes & Monsters is probably best remembered today for its TV movie version, which aired in 1982 and featured Tom Hanks in his first leading role as Pardieu the Holy Man, freaking out on the streets of New York, then trying to jump off the World Trade Center. (“I have spells,” he says. “I’m going to fly.”)

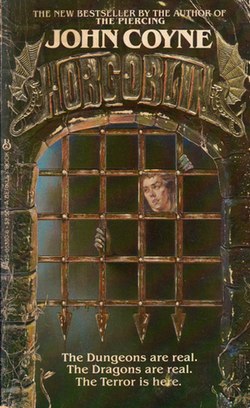

It’s an unwritten rule that if you’re going to try to make a quick buck off a young person’s attempted suicide you should at least be entertaining. Jaffe broke that rule, but the next book would not repeat her mistake. John Coyne was a slick journeyman writer, turning out relatively forgettable mass market horror paperbacks in the wake of Stephen King’s massive success. He earned a living with books like The Legacy (1979), The Piercing (1979), and The Searing (1980) but not a whole lot of respect. To his credit, his cash in attempt, Hobgoblin (1981), isn’t a thinly veiled account of Egbert’s story and the result is a book that is, as Kirkus puts it, “…considerably less offensive than The Piercing or The Searing.”

Meet Scott Gardiner, exactly the kind of kid Jaffe warned us was vulnerable to the lurid lure of RPGs: brilliant, creative, socially awkward, and WITH A DEAD FATHER OMG NO THIS KID IS DOOMED. Scott is obsessed (OBSESSED I TELL YOU!) with a truly terrible RPG called Hobgoblin that may be less boring than Mazes and Monsters but only just barely. One part RPG, one part Magic: The Gathering, it’s based on Celtic mythology so it’s full of unfortunate character names like “Boobach” and questionable spells like “fairy vision.” Players speak in fraught, reverent tones (“The dice? Oh, God, Gardiner, no! It’s too risky.”) and, in a deeply unrealistic touch, Scott is wildly popular after introducing this role-playing monstrosity to Spencertown, his fancy boarding school. But he’s not attending some fancy boarding school anymore. After his dad died (while Scott was playing Hobgoblin!!!!!!!!!!) he got sent to public school where his skill as the 25th level paladin, Brian Boru, doesn’t make him an object of admiration, it makes him a creep.

Meet Scott Gardiner, exactly the kind of kid Jaffe warned us was vulnerable to the lurid lure of RPGs: brilliant, creative, socially awkward, and WITH A DEAD FATHER OMG NO THIS KID IS DOOMED. Scott is obsessed (OBSESSED I TELL YOU!) with a truly terrible RPG called Hobgoblin that may be less boring than Mazes and Monsters but only just barely. One part RPG, one part Magic: The Gathering, it’s based on Celtic mythology so it’s full of unfortunate character names like “Boobach” and questionable spells like “fairy vision.” Players speak in fraught, reverent tones (“The dice? Oh, God, Gardiner, no! It’s too risky.”) and, in a deeply unrealistic touch, Scott is wildly popular after introducing this role-playing monstrosity to Spencertown, his fancy boarding school. But he’s not attending some fancy boarding school anymore. After his dad died (while Scott was playing Hobgoblin!!!!!!!!!!) he got sent to public school where his skill as the 25th level paladin, Brian Boru, doesn’t make him an object of admiration, it makes him a creep.

Coyne doubles down on Scott’s creep-factor. Sure, his mom uprooted him after the death of his dad and moved them to be near her new job in Ballycastle (an ancient Irish castle brought over to America by a rich guy at the turn of the century), but Scott is a whiny jerk with a hair trigger temper. When Valerie, the resident hot girl at school, falls for him because he memorizes his locker combination so quickly, he tries to make her play Hobgoblin, gets angry when she doesn’t take it seriously enough, then erupts into a rage when she calls him a “turkey” (“Kids say it to each other all the time,” she explains. “Not at Spencertown. I never heard it at Spencertown.” he mutters, darkly). When she finally agrees to play his stupid game the first thing he does is have three different NPCs try to rape her character. 1981, everybody!

Scott continues trying to prove to everyone at school how cool Hobgoblin is. It is not cool. In fact, because of Hobgoblin, his mother is murdered, Scott is attacked, and Valerie is kidnapped, stripped naked, and almost raped by the school bullies. (There is a LOT of attempted rape in this book.) Throw in a subplot about a crazy woman living secretly on Ballycastle grounds, a series of serial murders in Ballycastle’s past, and a bunch of 19th century S&M photos, and by the time the climax arrives you think you’re ready for anything. Turns out, you aren’t ready for this climax.

After a ambling along like a relatively slow-moving character study for 18 chapters, chapter 19 is a gibbering, blood-drenched scene from a slasher movie. Set during the school’s Halloween dance, almost every single secondary character is gruesomely slaughtered in just 42 pages, then there’s a brief one-page epilogue in which a happy Scott returns to his fancy boarding school where people really understand him. Also, now that he has murdered a man, he decides that he’s a grown-up and no longer needs to play Hobgoblin.

Egbert’s 1979 disappearance helped spark the anti-D&D moral panic that lasted for most of the 1980s. It lasted longer, in fact, than Egbert did. In 1980, he tried to kill himself again and this time, sadly, he succeeded. William Dear’s cavalier statements to the press helped spark this bonfire of the inanities, but when he published his own true crime account of Egbert’s disappearance in 1984’s The Dungeon Master, the only totally over-the-top thing about it was his author’s photo, pictured here. In the book, Dear makes it clear that Egbert was deeply unhappy, under a lot of pressure, and disappeared (and later killed himself) for reasons that had nothing to do with D&D. Of course, that doesn’t keep him from writing about the game in tense, melodramatic language: “My Dungeon Master and his friend arrived promptly at 2PM…For reasons I can’t explain, I tingled with anticipation and curiosity,” he reports.

Egbert’s 1979 disappearance helped spark the anti-D&D moral panic that lasted for most of the 1980s. It lasted longer, in fact, than Egbert did. In 1980, he tried to kill himself again and this time, sadly, he succeeded. William Dear’s cavalier statements to the press helped spark this bonfire of the inanities, but when he published his own true crime account of Egbert’s disappearance in 1984’s The Dungeon Master, the only totally over-the-top thing about it was his author’s photo, pictured here. In the book, Dear makes it clear that Egbert was deeply unhappy, under a lot of pressure, and disappeared (and later killed himself) for reasons that had nothing to do with D&D. Of course, that doesn’t keep him from writing about the game in tense, melodramatic language: “My Dungeon Master and his friend arrived promptly at 2PM…For reasons I can’t explain, I tingled with anticipation and curiosity,” he reports.

Ironically, for all that Dear, Jaffe, and Coyne posit that RPGs are a way for disturbed individuals to escape from reality, it turns out that they themselves were the ones running from the truth, fabricating a fear of games that hadn’t harmed anybody, based on false information about a missing persons case involving a young man who killed himself right before their books came out. Roll new characters, guys. Your last turn sucked. You three need to try again.

Grady Hendrix is the author of Satan Loves You, Occupy Space, and he’s the co-author of Dirt Candy: A Cookbook, the first graphic novel cookbook. He’s written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today and he’s the author of the upcoming novel, Horrorstör, about a haunted Ikea.