In Which the Noldor Plant Flags and Raise Towers, Ulmo Plays Favorites, Turgon Goes Isolationist, and Galadriel Gets People Talking

If you’ve made it this far into The Silmarillion, dear reader, this is where J.R.R. Tolkien gives you the chance to show your quality. “Of Beleriand and Its Realms,” Chapter 14 of the Quenta Silmarillion, is a literary map, and it’s the one where the professor really nerds out on names, places, and earth science, going nomenclative and topographic to the max. This is his jam. There’s no dialogue, action, or conflict, yet it’s fairly important stage-setting for what’s to come. It even features a not-so-fleeting Lord of the Rings crossover. But I sure hope you like maps!

Fortunately, in Chapter 15, “Of the Noldor In Beleriand,” drama and intrigue are not so scarce. Turgon keeps on keeping on for Gondolin—you know, the Elf city that’s so famous it even gets a mention in The Hobbit!—and Galadriel starts to spill the Noldorin beans.

Dramatis personæ of note:

- Turgon – Noldo, Fingolfin’s kid, daydream believer

- Ulmo – Vala, far-sighted Lord of Waters

- Galadriel – Noldo, Finarfin’s kid, goldilocks, chatterbox

- Finrod – Noldo, Finarfin’s kid, cave-hewing overlord of Nargothrond

- Angrod – Noldo, Finarfin’s kid, whistleblower

- Melian – Maia, cool-headed Queen of Doriath

- Thingol – Sinda, hot-hearted King of Doriath

Of Beleriand and Its Realms

This chapter (re)introduces the various Elven holdings in Beleriand, which seems to be the busiest corner of Middle-earth. Yeah, there are other regions of the continent, and even other continents, based on map sketches Tolkien made. We know that the Avari, the Unwilling Elves, are still way out to the east, and that all Men and many Dwarves have been milling about there for some time now. But as The Silmarillion is primarily concerned with the Noldor and their impact on history, and of course with Morgoth himself, it’s with Beleriand that we need to become familiar.

I admit, I do want to know more about the lands of Rhovanion, Harad, and Rhûn in these ancient days—all places stamped near the edges of more familiar maps in The Lord of the Rings—but Tolkien doesn’t give us much information about them, and certainly not in The Silmarillion. So let’s just work with what we’ve got.

You might think that this chapter could just be replaced with a quality atlas, and that would be most welcome. But it’s Tolkien’s descriptions and the emphasis he places on certain regions that solidify this time and place of the First Age. We’ve already been introduced to the Noldor princes and Sindar lords, but now Tolkien is making sure we’re all on the same page about where they’ve settled and what lands they control. You know, before things start to get hairy…

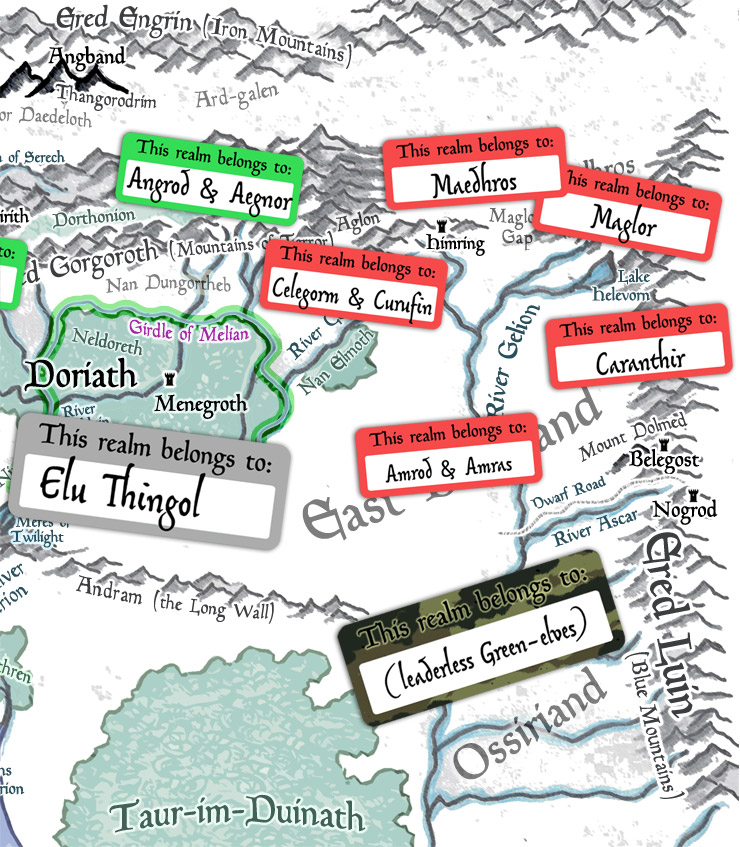

So who is in power, and where?

Morgoth, of course, is the big baddy up in the north, flanked by the Iron Mountains (which he himself raised back when he was the Vala formerly known as Melkor and could actually do crazy things like that). With his original HQ of Utumno trashed by the Valar long ago, it’s in “the endless dungeons of Angband, the Hells of Iron,” that he’s now consolidated his power. Morgoth has lost too much of his ancient potency to go pulling up whole mountain ranges again, but he was at least able to erect the three peaks of Thangorodrim to guard his underground fortress. Although we do learn in this chapter that Thangorodrim isn’t even proper mountain material; rather, it’s the “ash and slag” and “vast refuse” from his workshops and digs. It’s all the crap he displaced when he had his later tunnels dug out, just molded into it mountain-shaped peaks. It’s like Morgoth’s Super Sculpey® baked with volcanic heat—except replace the polymer with, you know, evil.

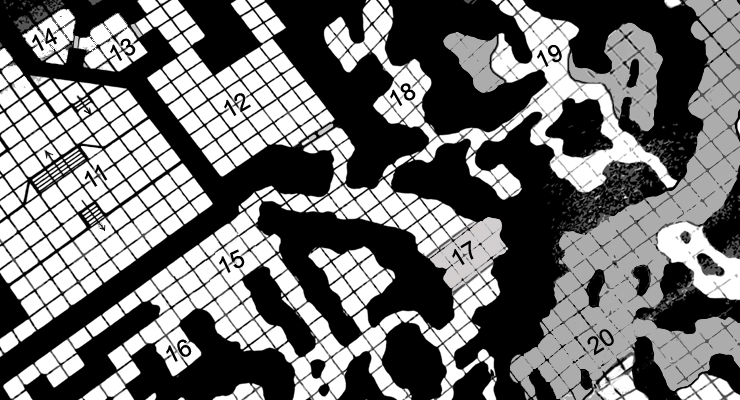

As an aside: this information implies that the vaults and dungeons of Angband are at least as deep as Thangorodrim is high, and who knows how wide? The Labyrinths of the Hells of Iron sounds like an epic oldschool dungeon crawl module, is what I’m saying. While the weakest of Orcs guard the 1st level, elite Orcs and the Elf-slave mines are found maybe on the 5th, trolls on the 8th, young fire-drakes on the 12th, and Balrogs won’t appear until, say, the 15th level. Morgoth’s throne room is, of course, the final chamber on level 20. I bet there’s even a place the heroes have to pass through where all the reeking slag and refuse gets hauled up by Orcs.

But no wonder the three peaks of Thangorodrim stink, while smoke fumes out of their tops like the worst industrial factories you can imagine. For miles outside the gates, the plains of Ard-galen are thus polluted and desolate…

but after the coming of the Sun rich grass arose there, and while Angband was besieged and its gates shut there were green things even among the pits and broken rocks before the doors of hell.

Which is an awesome little nose-thumbing at Morgoth. Even from across the world Yavanna’s little green seedlings thrive like grass sprouting up through cracked pavement. I bet an Orc is sent out every now and then with a WeedWacker™ but it’s never really enough.

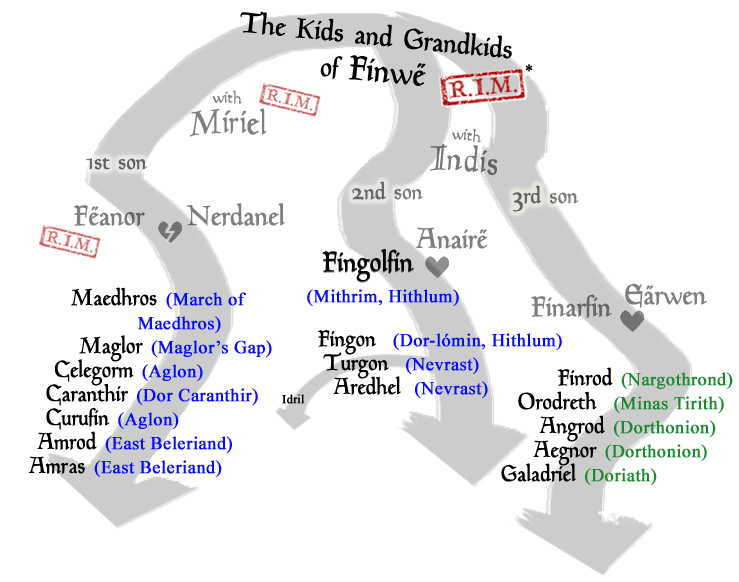

As far as the Elves go, there are two primary groups in Beleriand. There’s Thingol and the Sindar, which includes Círdan and his Havens and to a lesser extent, the Green-elves of Ossiriand. Then there are the Noldor, whose rulership is divided into the three houses of the sons of Finwë: Fëanor, Fingolfin, and Finarfin.

With Fëanor offed in the previous chapter, his seven sons have become the Dispossessed side of the house. His eldest, Maedhros, calls most of the shots in the family and for those Noldor faithful to them. Fingolfin is still around, along with all his kids. And then there’s Finrod, who now stands in for his dad, Finarfin (who stayed behind in Valinor with his wife, Eärwen), and all their younger siblings.

All right, so where are they now?

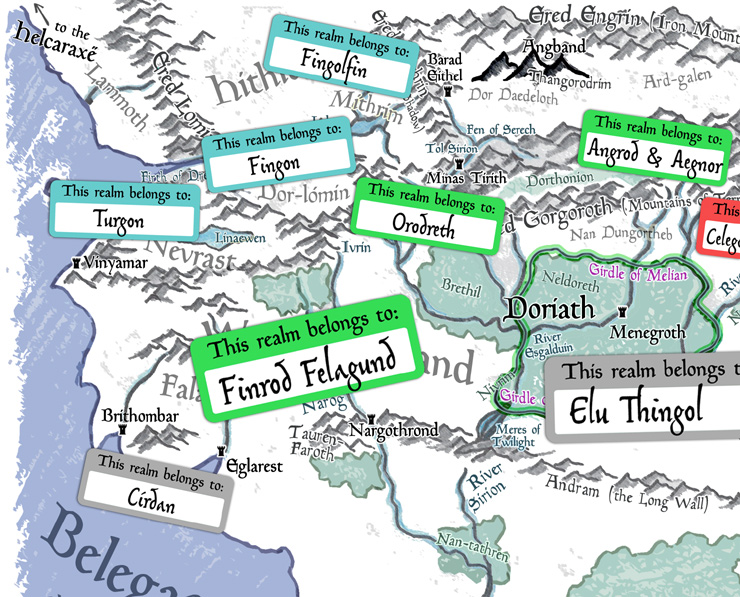

Well, west of Angband and across the Mountains of Shadow are the misty lands of Hithlum, where Fingolfin and his eldest son, Fingon, have set themselves up to maintain the leaguer against Morgoth. Fingon takes the westerly Dor-lómin half and his dad takes the easterly Mithrim half. A watchtower, Barad Eithel (“Tower of the Well”), serves as their main fortress, and it’s literally the closest Elven stronghold to Angband. Fingolfin is not kidding around when it comes to being “the most steadfast” of the sons of Finwë.

South and west of Hithlum is the Nevrast region, a cliff-, hill-, and mountain-ringed coastal region where Turgon, son of Fingolfin, and a whole bunch of Noldor first settled. In the middle, there’s a great big mere, which is a sort of swampy lake with “no certain shores” and plenty of birdwatching opportunities. Interestingly, Nevrast is kind of a melting pot of a realm, since lots of Sindar were already living here by the shores—since they used to be Teleri and we all know what Teleri think of waterfront property. Here in Turgon’s realm they get along swimmingly. Vinyamar is the name given to the cliffside settlement from which Turgon governs—but as we’ll see below, these halls are just holding him over temporarily. Even as he lives here with his little sister, Aredhel, he’s dreaming up a secret new city.

Now, just south of Morgoth’s front yard is the highland of Dorthonion, which is where Angrod and Aegnor, brothers and vassals of Finrod, set up shop for their part in the leaguer. It’s comparatively barren, and surrounded by some pretty scary mountains, but this region makes a massive barricade between the forest-realm of Doriath and Angband.

By gentle slopes from the plain it rose to a bleak and lofty land, where lay many tarns at the feet of bare tors whose heads were higher than the peaks of Ered Wethrin: but southward where it looked towards Doriath it fell suddenly in dreadful precipices.

That’s right, many tarns and bare tors! Tarns are small mountain lakes, and, well…another name for a high craggy hill is:

Just sayin’.

Further south, Finrod Felagund is the lord of Nargothrond, which is the name of both his cavern stronghold and his wide-ranging realm. Finrod is considered “the overlord of all the Elves of Beleriand between Sirion and the sea” (effectively all of Western Beleriand) and that sovereignty also extends up into the Pass of Sirion. There in that pass, on the river island known as Tol Sirion, Finrod constructs a watchtower called Minas Tirith. Yup, a very familiar name! And it just means Tower of the Guard. (Those later Gondorians sure liked Sindarin nomenclature!) From Minas Tirith, Finrod is able to help keep an eye in Morgoth’s direction as well, although he hands this tower’s rulership to his little brother Orodreth.

Over on the coast, Círdan the Shipwright is the leader of his group of Sindar, “who still loved ships,” and who are based out of the Havens of Eglarest and Brithombar. But he gets along really well with Finrod; there aren’t any territorial disputes between them, because honestly they’re just both great guys.

Then, of course, there’s Doriath and its forests of Neldoreth, Region, Brethil, and Nivrim—most of which are secured by Melian’s Girdle of Realm Protection +5. Elu Thingol is here called the Hidden King, which is a pretty sweet title, and because of his wife nothing can enter his realm without his permission. And that’s not just some law; this is a metaphysical barrier that the Maia herself had woven long before (four whole chapters ago). Nothing less powerful than Melian herself can pass: one does not simply walk into Doriath—especially evil things, like those creatures lurking just beyond the northern border.

Those evil things to the immediate north of Doriath dwell in the narrow land called Nan Dungortheb, which means Valley of Dreadful Death. Definitely not a place anyone wants to go. The Elves who have no choice but to pass through it make all haste when they do. And why the ominous name? Because the “foul offspring” of Ungoliant occupy those ravines and fill them with their “evil nets.” The whole place is just bad news. It would be crazy if, say, a lone mortal Man went wandering through there.

I’m just saying, it could happen…someday…

Oh, and there is a stretch of mountains on the western corner of the Ered Gorgorth called the Crissaegrim (Kris-SY-grim), which is where Thorondor and the Eagles dwell in their eyries. No one can reach them way up there, and they certainly play no political role in Beleriand. They’re basically just the eyes in the sky for Manwë, occasionally lending a helping talon—but only under specific, if mysterious conditions.

East of Doriath, we have the wide open lands and “hills of no great height” that Maedhros has taken charge of and aptly named the March of Maedhros. Into this region he brought the other six sons of Fëanor, mostly to keep them away from the other side of the family. While Maedhros governs his people from a citadel on the Hill of Himring, he has his little brothers take charge of the regions around it, always keeping himself between Angband and East Beleriand.

Celegorm and Curufin, two highly skilled asshats who’ll cause a great deal of trouble in the future, defend the Pass of Aglor between the March of Maedhros and the mountains of Dorthonion. (And with Celegorm is a fantastic dog whose master totally doesn’t deserve him and who gets no mention here but damn it, he’s here—most likely keeping the Pass of Aglor free of wolves. What a good boy!) Meanwhile, brother Maglor watches the flatter lands in the east, and brother Caranthir operates out of the vales and mountains closer to the Dwarf cities of Belegost and Nogrod. Finally, the two youngest, Amrod and Fëanor Jr. Amras, just sort of hang around the grasslands and woodlands further south, big game hunting and posing with the trophy kills of Yavanna’s most beautiful creatures, I’d expect. Just generally being typical jerk sons of Fëanor.

Still with me? Good. Because finally, in the southeast quadrant of Beleriand is Ossiriand, the Land of Seven Rivers where the woodsy Green-elves live, leaderless and overcautious. I’m not saying they’re xenophobic, but ever since they lost their Elf-lord, Denethor, in the first of the Wars of Beleriand, they’re not the most trusting of the Eldar. Camouflaged in their everyday togs, the Green-elves excel at keeping out of sight “such that a stranger might pass through their land from end to end and see none of them.” But you know, that’s better than peppering said stranger with arrows—which is something they’re not totally against, as we’ll see in a few more chapters.

One very notable exception is Finrod, who loves to wander even outside of his own realm of Nargothrond, and who—no surprise—becomes easy friends with the Green-elves when he visits them. Finrod’s the best.

Of course, all these kingships and overlordships are presented from the point of view of the Eldar.

But let’s be honest: it depends on who you ask. I mean, some people—even those shut up in their creepy fallout Daystar shelters—might claim ownership of all of Beleriand, if not the whole world.

So anyway, that’s the basic geographic, political, and geopolitical state of affairs in Beleriand and its environs at this point in The Silmarillion. I know, I know: learning about the basics of Elven geopolitics isn’t exactly why most of us are probably reading Tolkien. But again, this is all important stage-setting. And hey, at least we’re zoomed way out and don’t have to sit through the minutiae of trade negotiations and senate meetings, right? Although frankly, if Tolkien had written about the economic nuances of the Naugrim and their trade partnerships in Beleriand, or if he’d written out every word spoken at the Entmoot, I think it would be a fine read, even as just an Appendix. But maybe that’s just me.

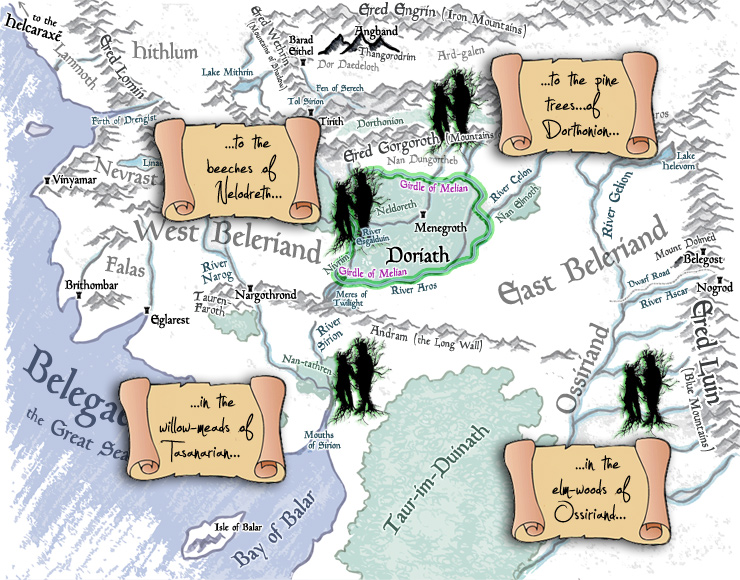

Oh, and speaking of Ents! As many readers have noted before me, some of the places named in this chapter are remembered first-hand by some of the venerable characters in The Lord of the Rings! Case in point: Treebeard himself once roamed Beleriand and fondly recalls some specific sites in the chant he shares with Pippin and Merry. Rather than just list them, here’s my Beleriand map with the highlights of Treebeard’s apparent walking tour.

Or, better still, go and reread his lovely song. And then listen to Christopher Lee’s excellent, if strangely creepy version of the same with the Tolkien Ensemble.

All right, one last thing. I would be doing the professor a disservice if I only hurried through the Elf realms and kingships, because Tolkien famously loved writing about the natural world, too. And to him, the geographic features of Middle-earth are as important as the political ones. They play their part. Nargothrond, for example, wouldn’t be half as defensible without its placement alongside a gorge of the River Narog, nor would Doriath be as difficult to invade—Girdle or no Girdle—without the highlands of Dorthonion situated where they are.

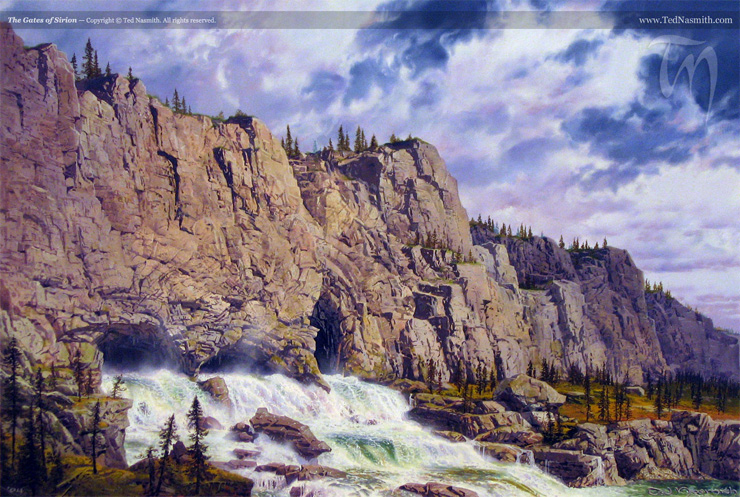

So let me at least point out the “mighty river Sirion, renowned in song.” Funny enough, we’re told explicitly in a paragraph about a different river that…

after Sirion Ulmo loved Gelion above all the waters of the western world.

Which is awesome, because this means Ulmo has a list of favorite rivers—rivers he no doubt had a hand in making and/or shaping, probably after the fall of the Lamps of the Valar a bajillion years ago—and Sirion obviously beats out Gelion! The narrator also points out that Sirion is what essentially draws the line between West Beleriand and East Beleriand. At one point it—no, he (Tolkien personifies the rivers in this chapter)—comes down a great waterfall before plunging into underground tunnels and then issuing from huge stone arches. And these are known as the Gates of Sirion.

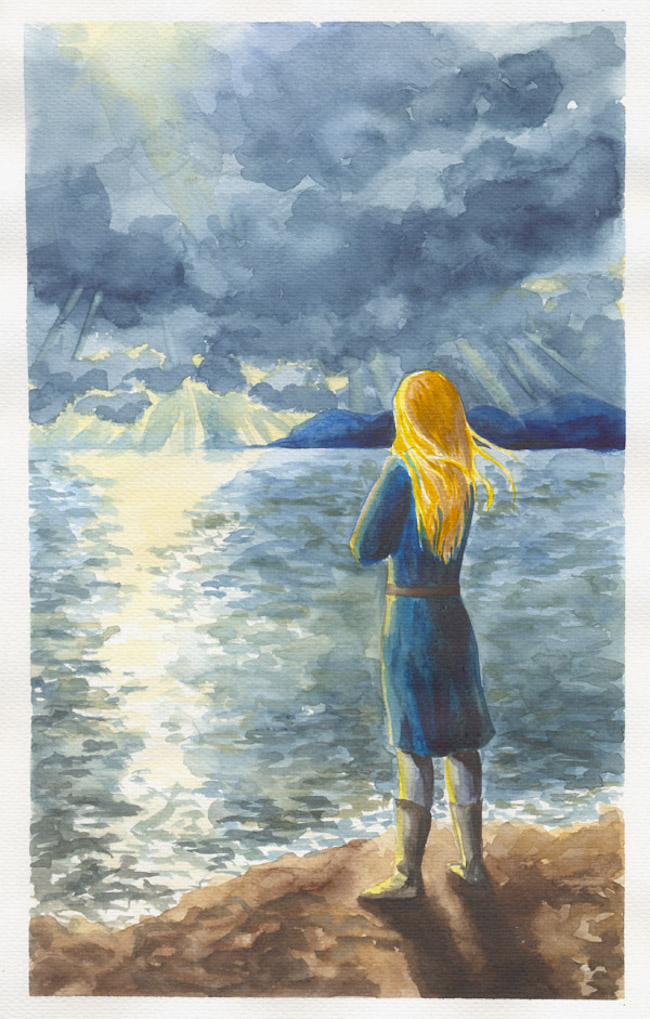

Which now fully justifies my sharing yet another amazing Ted Nasmith painting.

And if I say anything more about this chapter, I’ll lose the newbies. Maybe even some of the old guard. So let’s move on to the next chapter.

Of the Noldor In Beleriand

Okay, so that’s not the most informative title, but this chapter marks a turning point for the Noldor in the First Age. To recap: they’ve been banned from Valinor, they’ve settled in Middle-earth, and they’ve butted heads with the forces of Morgoth (and to a lesser extent, butted heads amongst themselves). Now what?

Well, recall that Ulmo, the Lord of Waters, isn’t good at idling. He “dwells nowhere long,” for one, and “even in the deeps” news comes to him that Manwë himself doesn’t get. He has some ideas about the sort of shit Morgoth is going to start slinging, and wants to help the Elves prepare for it. At first he did so unobtrusively: two chapters ago, he planted the seeds of secret stronghold construction into the dreaming heads of both Turgon and Finrod. Presumably because he thinks these two cousins are (1) the most apt to take his warning seriously, and (2) the best equipped to see it through. They’re very different fellows, but they’re both Noldor princes at the top of their game.

Finrod’s already got his stronghold of Nargothrond in place, but Turgon’s just been drawing sketches of his city in Nevrast…until now. After that last battle against Morgoth’s Orcs, a period of peace settled over the land. So finally Turgon gets to work. He takes his best architects and builders and leads them to the hidden valley of Tumladen in the Encircling Mountains (due west of Dorthonion) and they set about building Gondolin. It takes fifty-two years of “secret toil” to build it, which seems like a long time to us but wouldn’t be to an immortal Elf. Then again, we’re talking about an entire city, and one that’s fashioned in the memory of Tirion over in Eldamar.

When he’s finished, Ulmo comes to Turgon in Nevrast one last time for some prophetic chit-chat. He tells Turgon that:

- It’s time for all his people to occupy Gondolin full-time.

- He, Ulmo, will use the waters of Sirion (still #1 in Ulmo’s Top 40 Rivers charts) to hide the secret paths into Tumladen.

- Gondolin will hold up against Morgoth longer than any of the other Elves’ strongholds.

That last bullet point is a bit alarming, though, because on the one hand, sweet!—Gondolin’s the best fort ever!—but on the other, holding out “longest” implies it’s still bound to fall. And in fact, they all will. *gulp* So now it’s just about making Gondolin last as long as possible. Additionally, Ulmo warns him…

But love not too well the work of thy hands and the devices of thy heart; and remember that the true hope of the Noldor lieth in the West and cometh from the Sea.

Which sure sounds like something a sea-based Vala would say, doesn’t it? But actually, Ulmo isn’t referring to himself. And at no point is he trying to say, hey, if we really work at this, maybe we can hold off Morgoth indefinitely, or even beat him. He’s saying the Noldor aren’t going to win on their own. Something or someone will be coming from the sea to help achieve that. Ulmo goes on to remind Turgon that his people are still “under the Doom of Mandos,” and there ain’t no nothing he can do about that. Being under that Doom means treachery may come from within Turgon’s own city because the Noldor have introduced the very concept of treachery among their own by virtue of the Kinslaying. And it’s treachery, not Orc spies, that Turgon will need to watch out for.

But as one last bit of help, Ulmo says that when threats to the hidden city do draw near, then Turgon will at least get a heads-up. This warning will take the form of a dude coming from Nevrast. Who will this be? Ulmo doesn’t say. But hey, Turgon, maybe leave behind a specially commissioned shield, hauberk (coat of mail), sword, and helm for said dude as a way of proving it’s the right guy? The Lord of Waters even has the specs for the armor. He’s simultaneously rather vague and yet weirdly specific. That’s just how Ulmo flows.

And then he returns to the sea. I’ll admit, one thing bothers me about this. Remember, Ulmo troubled both Turgon and Finrod with stronghold-building dreams. So…either he thinks Finrod can handle things on his own or he simply favors Turgon. We’re not really told why he only follows up with one of them. I keep imagining Ulmo texting Turgon a little while later as a sort of afterthought on his part.

And with that, Turgon grabs all his people, a bunch of Fingolfin’s (a whole third!), and tons of Sindar, and he leads them, group by group, to his hidden city. Presumably he gave them all a choice—Turgon doesn’t really throw his political weight around until later—but for those who follow him there’s no going back. And there certainly aren’t any clues left lying around as to where they all went to. Nothing for Morgoth’s people to find. No footprints, no candy wrappers, no Encircling Mountains brochures with the route to Gondolin marked in red ink. They all just appear to vanish from Beleriand, aided by Ulmo’s influence in and around the Vale of Sirion. It may be that mists rise to conceal them, or wandering Orc scouts suddenly find the streams and rivers too turbulent to cross in the vicinity. Who knows? With a Vala actively helping Turgon and his people, there was just no way anyone was going to detect them.

The land of Nevrast is then left totally abandoned—well, except for that shield, sword, and armor Turgon stashed. It seems like he doesn’t even send a note to his dad or his brothers about where he’s gone to. It’s that secret. Gondolin, the Hidden City, isn’t joking around with its name. But Turgon does bring his baby sister, Aredhel, with him. And also his daughter, Idril—who, no, we’ve never heard of until this moment. Which makes her the great-granddaughter of Finwë. (See the fine print.) Since Turgon’s wife was lost in the crossing of the Helcaraxë, that means Idril was already around at that time—so while she’s clearly young for a Noldo, she’s still Calaquendi and already at least hundreds of years old at this point. Just a young Elf-maid who saw the light of the Trees with her own eyes.

In any case, it turns out Turgon is really good at what he does, because Gondolin is amaaaaaaazing. It’s a legit rival to Tirion, too—the city which Turgon intended to memorialize and echo in its design and construction:

High and white were its walls, and smooth its stairs, and tall and strong was the Tower of the King. There shining fountains played, and in the courts of Turgon stood images of the Trees of old, which Turgon himself wrought with elven-craft;

And let me tell you, Gondolin is one safe-ass city. It’s built on a great hill of smooth and hard stone in a valley ringed by tall mountains, and the only paths in are concealed by Valar-augmented waters. You might wonder, couldn’t something just fly over the mountains and spy Gondolin? Sure, but Morgoth has no—no!—winged minions at this time. The only creatures who can see inside the valley are mountain-dwelling birds and the Eagles who nest in the Crissaegrim—and they ain’t tellin’ nobody nothin’! (Except, of course, Manwë.)

So Gondolin shuts its mountain gates, and no one is getting in from this point on! (I mean, mostly.) And Turgon’s military force won’t ever be going out again, either.

“Spoiler” Alert: Oh, wait. So there are going to be two guys who are going to be allowed into Gondolin at some point: one named Húrin and one named Huor—whoever they are! But they won’t arrive by the secret gates. Oh, and Turgon himself will depart with soldiers in three hundred and fifty years during something called “the Year of Lamentation.” Yeesh, that can’t be good. Then, because Tolkien is a fan of the one-two punch, he just tosses this in like nothing:

Thus Turgon lived long in bliss; but Nevrast was desolate, and remained empty of living folk until the ruin of Beleriand.

Who does he think he is—Mandos, all of a sudden? I guess all of Beleriand is getting ruined at some point. Great. In any case, I have to say it: this is why the Elves can’t have nice things (for longer than a few hundred years, anyway). Especially under the Doom of Mandos.

Then we pan over to Doriath and rewind a little bit. While Gondolin is still under construction, and while her brother Finrod is still tinkering around in Nargothrond, Galadriel has been hanging out with her friend Melian! You know, the Maia queen. Starting with this chapter, you get the sense that Thingol clearly doesn’t listen to his wife half as much as he ought to. (But maybe that’s just a temporary phase? I mean, why wouldn’t you listen to your spouse if she was one of the Ainur who helped sing the universe into existence?) In contrast, Galadriel learns everything she can from her powerful mentor. Now, if we know Galadriel from The Lord of the Rings and the sort of leader, counselor, and caretaker of the last vestiges of Elvendom that she later becomes, it’s very clear that she learned so very much from Melian. She is a huge part of Galadriel’s origin story.

These two women bond over the memory of the Bliss of Valinor and of the Two Trees, Galadriel’s memories stemming from two or three ages of Morgoth’s captivity (during which she would have been born) and Melian’s from since the Trees’ actual creation. Yet, Melian and Galadriel would have never shared that Trees’ light together: Melian left Valinor before the coming of the Elves and then met her future husband during the great march of the Eldar.

Melian knows about the Darkening of Valinor, of course—remember, she essentially told Ungoliant to piss off when the she-spider came too close to Doriath and has fashioned her Girdle to keep Morgoth’s servants out as well—but it’s important to remember that even though she’s a Maia, she’s in an Elf-like body and has been for a long time. She has no news from Valinor, no informants who bring her word from afar. Not even from Ulmo, who you’d think would at least have some way of conveying information through the waters that run through the woods of Doriath. But Melian won’t, and probably can’t, go about in unclad spirit form and drift abroad—not unless she relinquishes her current setup. But she hasn’t. She has people to protect, a husband, and a life among the Children of Ilúvatar.

She’s also smart and insightful to the max. She asks Galadriel what troubles her; she can see that her friend—and possibly the Noldor at large—have been carrying a heavy spiritual weight ever since their return. She tries to draw the truth from Galadriel, but the future Lady of the Golden Wood is evasive. Melian doesn’t buy that the Noldor came to Middle-earth as messengers of the Valar, for no messages have been delivered (which is a funny thing to point out now, after the Noldor have been back for hundreds of years). And this is fair, but it’s not like the Noldor have explicitly claimed to be sent by the Valar; they just haven’t denied it. Melian suggests the Noldor might have been “driven forth as exiles” and notes that the sons of Fëanor seem to be involved, what with their sucky attitudes. She asks if she’s near the mark.

‘Near,’ said Galadriel, ‘save that we were not driven forth, but came of our own will, and against that of the Valar. And through great peril and in despite of the Valar for this purpose we came: to take vengeance upon Morgoth, and regain what he stole.’

Then, like Angrod two chapters ago, she goes all Chatty Cathy. And just like her brother, Galadriel (the Garrulous?) omits some things, such as the Oath, the Kinslaying, and the stealing and subsequent burning of Teleri ships. She does talk of the Silmarils and of Morgoth’s slaying of Finwë after the Darkening of Valinor. Melian, being Melian, reads between the lines and infers a great deal more that her friend isn’t saying. If we remember Galadriel seeing into the hearts of each member of the Fellowship in Lothlórien, this is her getting a foretaste of her own medicine.

Well, soon after, Melian talks with her husband and shares what she’s learned. She combines this knowledge with her own warnings—which Thingol will almost completely disregard—that the shadows that cling to the Noldor have the fate of all of Arda wrapped up in them. Thingol has got to be careful about how to handle them. Melian also says, as only a foresighted Maia (or a dying Fëanor) might, that the Silmarils will not be reclaimed “by any power of the Eldar; and the world shall be broken in battles that are to come” before they’re retaken from Morgoth. With that rather alarming notion, you’d think that Thingol would take Melian’s words into account going forward. But right now, he’s grieving for Finwë and angry at all the secret-keeping Noldor. Melian specifically warns him about the sons of Feanor in particular, but he mostly just thinks to use them as a weapon against Morgoth.

Speaking of…

Remember that during this time, this period of long peace throughout which Morgoth is literally beleaguered by the Noldor and kept holed up in his basement, he’s still able to send out spies and “whispered tales.” Thus rumors, alternative facts, and even some choice truths start to circulate among the Sindar about the Noldor, and they are “enhanced and poisoned by lies.” When they reach Círdan the Shipwright over at the Havens, he’s immediately suspicious of their origin.

Fascinatingly, Círdan doesn’t ascribe the rumors to Morgoth at all. Why would he? The Sindar, quite unlike the Noldor, never had Morgoth living among them in a fair-seeming form and seeding lies. We know this is classic Melkor stuff, and the Sindar just aren’t wise to it. To the Sindar, Morgoth is not subtle; he’s just been this big monster guy up in the North who sends out Orcs, not sinister lies and insults. So Círdan believes that these rumors going around must be the work of the jealous, contending princes of the Noldor. Probably those sons of Fëanor.

Either way, Círdan sends word to Thingol about what he’s heard and what he’s surmised—and it includes some of the stuff Galadriel didn’t talk about. Even more troubling stuff. So it’s from Círdan, not those directly involved, that at last Thingol—once considered a Teleri himself and the brother of Olwë, the king in Alqualondë—hears about the Kinslaying. You know, this thing…

Dun dun dunnnnn!

Now it’s time to wring the unfiltered truth out of the Noldor! No more dancing around it. Thus, the next time Galadriel’s brothers visit her in his court, Thingol confronts the eldest, Finrod, who is the head of the house. Finrod is embarrassed and evasive, only saying that the Noldor have done no harm in Thingol’s realm since their coming. He doesn’t start pointing fingers or blaming anyone else—even though he absolutely can—because that’s not who Finrod is. But his younger brother Angrod has no such inhibitions, especially when it comes to those contemptible, good-for-nothing sons of Fëanor, whose treachery led him, his family, and all of Fingolfin’s host into the nightmarish Helcaraxë.

Lord, I know not what lies you have heard, nor whence; but we came not red-handed. Guiltless we came forth, save maybe of folly, to listen to the words of fell Fëanor, and become as if besotted with wine, and as briefly. No evil did we do on our road, but suffered ourselves great wrong; and forgave it. For this we are named tale-bearers to you and treasonable to the Noldor: untruly as you know, for we have of our loyalty been silent before you, and thus earned your anger.

It’s like that old slogan: loose lips cite burning ships! Angrod has had enough! He goes on to throw the sons of Fëanor fully under the bus, dishing out all the dirt he can. The Kinslaying at Alqualondë. The theft of the Teleri ships. The Doom of Mandos. The burning of the ships. The goddamned Grinding Ice!

Thingol understands that the children of Finarfin aren’t specifically to blame for the Kinslaying, and didn’t personally participate in the slaying of their own mother’s kin. He gets that they were themselves betrayed by Fëanor and suffered the brutal crossing of the Helcaraxë for it. He even says that he won’t close his doors to the house of Finarfin later, for they at least are family. But right now? They need to get the hell out. Because, as Thingol admits, “my heart is hot within me” and in a rare moment of self-awareness, he knows he might say or do something he’ll regret later.

Yet one thing Thingol does enact right now with the full power of his kingship:

But hear my words! Never again in my ears shall be heard the tongue of those who slew my kin in Alqualondë! Nor in all my realm shall it be openly spoken, while my power endures. All the Sindar shall hear my command that they shall neither speak with the tongue of the Noldor nor answer to it. And as such as use it shall be held slayers of kin and betrayers of kin unrepentant.

And just like that, Thingol blacklists the Quenya language. Sure, the Noldor will speak it to one another privately, but the Sindar never will, and in the march of time Quenya won’t really grow and evolve like living languages should, and it will gradually fade from common usage. (Galadriel will use Quenya it in her parting song as the company leaves Lothlórien.)

Interestingly, most of the Elvish words used in The Silmarillion are Sindarin, not Quenya, which is proof positive that Thingol’s dictum holds. Even our narrator has been sticking mostly with Sindarin this whole time. For example, it is the Sindarin name of Gondolin, and not Ondolindë (which means “Rock of the Music of Water” in Quenya), that Elrond cites in The Hobbit. And as a more familiar example, Galadriel is a Sindarin name. In actuality, up to this point she would have been going by Artanis (at least, according to Unfinished Tales), but when her Sindar friends started using Galadriel (being the Sindarin variant of a pet name given to her by her boyfriend, Celeborn), she went with it. The point being, even in the Third Age, long after Thingol and his laws are gone, she still uses this Sindarin word when speaking to the Fellowship of the Ring. Quenya lives on merely “as a language of lore,” from this point forward.

Speaking of Galadriel, the chapter closes with what seems like the tail-end of a conversation between her and her brother, Finrod, when she visits him in his cool underground lair. She asks him why he hasn’t married. He is Finrod Felagund, King of Nargothrond and Lord of Caves! Everyone loves him. How has no one snatched him up yet?!

But Beleriand’s (seemingly) most eligible bachelor answers her with:

An oath I too shall swear, and I must be free to fulfil it, and go into darkness. Nor shall anything of my realm endure that a son should inherit.

It’s not until he is speaking with his sister that he realizes “such cold thoughts ruled him,” for which I kind of want to blame Galadriel. I know she’s going to be a wise ruler herself someday, who says profound things and knows stuff, who gives heavy, momentous counsel and mighty magical gifts. But can’t an Elf just have tea and biscuits with his sister without some high doom falling on him? I bet this happens with Galadriel all the time, though. She probably can’t even attend some Elf-kid’s birthday party without that kid getting some soothsaying remarks from her.

Anyway, so Finrod has this foreboding that he’s going to make an oath someday, and if he were married he would somehow be constrained from doing so. That’s the official reason why he’s not married. But we’re given the real reason in the last couple of lines of the chapter. See, Finrod has a girlfriend already—and theirs is a very, very long distance relationship indeed. His bonnie lies over the ocean.

The Great Sea, not to mention a little thing called the Doom of Mandos, now lies between them. She is Amarië, an Elf of the Vanyar back in Valinor, and it was she he’d been so hesitant to leave behind when his entire family packed up to follow that shithead Fëanor. Finrod’s not settling down with anyone because the Eldar only choose one partner (okay, except Grandpa Finwë), and the one he wants to be with is dwelling on the slopes of Taniquetil. Waiting for him. As he waits for her.

Earlier in this chapter, Ulmo warned Turgon about Gondolin, which was his pet project, his masterwork, his baby. He said, “love not too well the work of thy hands and the devices of thy heart,” right? Despite my joking, why does Ulmo never give Finrod any such warning? Because he doesn’t really need it. Corey Olsen, the Tolkien Professor, pointed out in his Silmarillion Seminar that Finrod has no such attachments in Middle-earth, no work of his hands that he loves too much. Sure, he’s got Nargothrond, but it’s just a place to guard his people. Quite unlike Turgon, he doesn’t shore himself up in isolation and never go out. Even though he’s a king, Finrod ventures out all the time, roaming Beleriand, hanging with the Green-elves, going on adventures, helping friends in need. And why? The devices of his heart are not here; they’re in Valinor.

If you ask me, the closing message of this chapter is clear: on Middle-earth, Finrod is living on borrowed time.

In the next installment, we’ll look at Chapter 16, “Of Maeglin,” and learn what it means to be a dark elf in Tolkien’s legendarium; a dark elf, that is, among Dark Elves. And in this, we’ll zoom in closer in on some new characters.

Top image: “Gondolin” by Stefan Meisl

Jeff LaSala plans on seeing if reading “Of Belerien and Its Realms” aloud will put his son to sleep at night (please God, please). Tolkien nerdom aside, Jeff wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, produced some cyberpunk stories, and now works for Tor Books.