Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

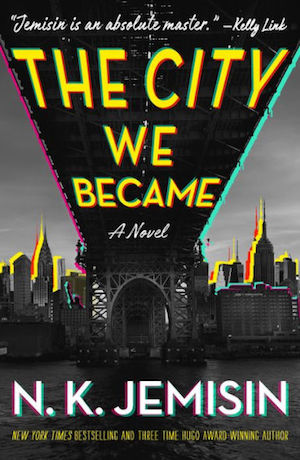

This week, we continue N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became with the Chapters 2-3. The novel was first published in March 2020. Spoilers ahead!

“I’ll miss this universe when everything is said and done. It’s hideous, but not without its small joys.”

Chapter Two: Showdown in the Last Forest

Madison drives Manny to the address he found noted in his bag. There he meets his roommate, a “lanky Asian guy” with a British accent. Manny asks his name, attributing his forgetfulness to a recent fainting spell. Bel Nguyen, his fellow grad student in political theory at Columbia, reveals they’ve met only via Skype. Manny shares his “nickname.”

The roommates explore nearby Inwood Hill Park, Manhattan’s last old-growth forest. Bel checks nervously on whether Manny’s amnesia has changed his mind about living with a trans man. Manny reassures him, and Bel confesses that over Skype Manny struck him as “an arse-kicker extraordinaire.”

Air cleared, they view the site of Peter Minuit’s 1626 purchase of Manhattan. Manny senses strange energies like those in the monster-quelling umbrella. This power seems omnipresent, focusing when Manny uses “the right combination of things? ideas? to summon it forth.”

A white woman approaches, filming them with her phone. She accuses them of “being perverts in public.” A tendril juts out the back of her neck. Manny demands she show her true self, and she shifts into a white-clad, white-haired cross between “a church lady and a female Colonel Sanders.” She mistakes Bel for “São Paulo” before realizing he’s “just human.” Manny she mistakes for the NYC avatar, but he doesn’t use the same “shit-talk.” He’s Manhattan. NYC “stubbed” her city “toe-hold,” and before Manny tore her from FDR Drive she infected enough cars to establish hundreds of other toes.

The Woman-in-White believes Avatar NYC is the city’s “heart,” while the five boroughs are its “head and limbs and such.” “Ghostly little white nubs” sprout from the asphalt. Only the energized earth around the monument remains clear of tendrils; Manny and Bel shelter within it. The woman, possessing entity departed calls the police to report drug-dealing perverts.

Manny intuits that the monument marks NYC’s original “real estate swindle”—Manhattan’s essence, then, is stolen value. He throws his and Bel’s money at the tendril-lawn. It shrivels, but their combined funds aren’t sufficient. Sirens herald the police, but a stylishly dressed Black woman with regal attitude arrives first. Her phone blares old-school rap, crumbling the tendrils. Manny subdues the racist woman with self-startling deftness—where’d he learn this art of studied violence? He deletes the pictures from her phone, then retreats with Bel and their savior.

Said savior turns out to be Brooklyn. Brooklyn Thomason. Former lawyer, current city councilor. Also formerly, the celebrated rapper MC Free. Leaving a crisis-response meeting about the Williamsburg bridge disaster, something led her to Manny.

Manny fears the other three boroughs need help, too. Seeing a tendril-infected dog convinces Brooklyn to join the search. Shortly afterwards both feel “the explosive, brilliant skylineburst” of another borough-birth. Queens, Brooklyn says. They send Bel home and hurry toward a bus stop, Brooklyn trusting public transport will lead them aright. But Manny fears they’re too late to help.

Chapter Three: Our Lady of (Staten) Aislyn

Thirty-year-old Aislyn Houlihan lives with her parents on Staten Island, home of “decent” people. She sometimes considers taking the ferry to Manhattan, but her policeman father’s right. The city would eat her up. It’s full of people you give one name at work and another name at home, where it’s safe to be honest about the illegals and liberals.

This morning, Aislyn suddenly heard vulgar, angry shouting in her head. Vicarious rage so overwhelmed her that she tore a pillow to shreds. Afterwards, something draws her to the ferry terminal. But someone takes her arm to hurry her during boarding, and the crowd jostles them, and then she sees the hand on her arm is black. She flees, screaming. Another hand grabs her. She scratches hard to escape, then runs toward the buses. A woman in white runs alongside. “But no one can make a city do anything it doesn’t want to,” she assures Aislyn.

Buy the Book

A Half-Built Garden

They halt. The woman holds her shoulders, comforting. She remains while Aislyn answers a call from her father and endures a typical rant about the Puerto Rican he arrested that morning. Meanwhile the Woman-in-White touches passersby, seeding tendrils in their flesh. But the woman can’t “claim”Aislyn, who even smells like a city now.

Aislyn’s rage revives, but the woman quells it by calling her “Staten Island,” the “borough no one, including its own, thinks of as ‘real’ New York.” There are five sub-avatars, the woman explains, and the monstrous primary avatar. Manhattan and Brooklyn have already united. They look for Queens and the Bronx, but haven’t even thought of Staten Island. If Aislyn allies with the woman to find the primary, Aislyn will be free of this “algal colony”!

It’s crazy, but nice to have a new friend. The woman points out a tendril protruding from the terminal. Aislyn only has to speak into such a tendril, and the woman will come running!

Aislyn asks the woman’s name. Her name’s foreign, hard to pronounce, but she whispers it in Aislyn’s ear. Aislyn collapses on the platform. Only the bus driver’s there when she comes to, arms breaking into hives. Aboard the bus, a petal dangles from the STOP REQUESTED sign. Aislyn recalls that the woman’s name started with R, and decides to call her Rosie, like the WWII poster. I WANT YOU was Rosie’s slogan, or something similar.

Aislyn feels “immeasurably better.”

This Week’s Metrics

What’s Cyclopean: Where last chapter the tentacles were anemones, this time they’re “Cordyceps, puppet strings, drinking straw”. All with different, and differently creepy, connotations. Brooklyn thinks they look more like pigeon feathers, creepy largely in the implication of pervasiveness.

The Degenerate Dutch: Aislyn’s father is open about his bigotries, but careful to distinguish work-safe insults like “immigrant” from “home words”. Extradimensional abominations are happy to use racism, homophobia, and transphobia like his as levers for mind control—or just plain manipulation. These things are hard enough on our characters even in the absence of Cthulhu, and magic doesn’t make them more palatable.

The Woman in White, meanwhile, has prejudices of her own. “Pardon me, I mistook you for fifteen million other people.” All cities look alike, and some individual humans look like cities.

Weirdbuilding: In the breakthrough quote from Queens, we hear an exasperated objection to the eldritchification of non-Euclidean geometry. “All that means is that you use different math!”

Madness Takes Its Toll: Bel hopes that the “terrorist” responsible for the bridge collapse is a white guy with mental health issues, even as he thinks that’s a hell of a thing to hope for. But at least it’s less likely to touch off hate crimes or wars.

Anne’s Commentary

Could Manny have found a better roommate than Bel Nguyen: smart and funny, with good taste in apartments and a British accent that shifts from Standard BBC to South London street dialect as the situation warrants? Bel is highly open-minded, an outlook his own Asian and trans identities have taught him to hope for (however cautiously) in others. Manny really needs a tolerant co-tenant. He’s barely inside the apartment before he challenges Bel’s credulity with his amnesia story. Then Manny “introduces” Bel to a shape-shifting bigot-alien and her tendril-worm-spaghetti pets. Equally weird if cool is Manny’s status as the very avatar of Manhattan.

Next introduced is Brooklyn Thomason aka rap idol MC Free, lawyer and city councilor and avatar of (yes) Brooklyn. Prepossessing as her queenly presence is, Manny sees beyond it. He experiences another shift into double perception and sees side by side the micro-world of present “reality” and the macro-world of a deeper reality. It reveals Brooklyn as Brooklyn, her “arms and core… thick with muscled neighborhoods that each have their own rhythms and reputations.” Her spires aren’t as grand as Manhattan’s, but they’re “just as shining, just as sharp.” In the instant of this epiphany, Manny “cannot help but love her,” the ideal and the “real,” a middle-aged woman “with a shining, sharp grin.”

Manny has a Ph.D. to pursue. Brooklyn has political duties, a fourteen-year-old, and an ailing father. Both must put aside personal responsibilities for those of their new compound selves. Manny has an additional burden in his forgotten identity. He’s different from Brooklyn. She’s a New Yorker born; he’s an out-of-towner. She was named to match her future borough-self; he was not. She remembers her past; he’s amnestic to the personal aspects of his. Precariously amnestic. Manny doesn’t want to remember who he was pre-NYC—clawing through his wallet, he deliberately avoids looking at his old ID. Bits of his history resurface, vague yet disturbing. He knows he’s faced death before. He has sick fighting skills—how, after all, did he get to be Bel’s “arse-kicker extraordinaire”? Manhandling Martha, he realizes he’s hurt a lot of people. He knows how to erase evidence from her phone. His Amex card clears tendrils from an impressive chunk of Manhattan real-estate—how high must his balance have been?

Who was pre-NYC Manny? His past must be part of what qualifies him to become not only the glamorous Manhattan, but the Manhattan founded on a real estate swindle, home to murderers, slave brokers, slumlords, stockbrokers. Facing this truth, he feels “a slow upwelling of despair.”

Slow despair is where Aislyn Houlihan starts off. She’s lived thirty years under a bigot father who uses his policeman’s authority to persecute the “illegals” and “libtards” infesting NYC and threatening SI, last enclave of normal, decent folk. Right-wing talk radio must play nonstop in Aislyn’s home, when it can be heard over Daddy’s rants. She’s well-indoctrinated into fear of the hydra-headed Other and resentment of the other four boroughs.

She does love SI. It’s her homeground. But curiosity about the larger world, about the city, still sparks in her. When Avatar NYC’s battle-fury reaches her, those sparks explode. She’ll finally take the ferry she’s avoided.

That Aislyn doesn’t take it, panicking when surrounded by Others, is what must decide the Woman-in-White to manifest. The newborn avatar of self-doubting SI, Aislyn is the most vulnerable borough, the one the Woman can manipulate. The Woman is herself an avatar of the Outer Enemy, protean, assuming whatever form serves best with the target-of-the-moment. To Manny, she looks like a cross between the stereotypical churchlady and Colonel Sanders, insidiously cheerful white icons. To Aislyn, she’s the Big City Woman she fantasizes being herself. She’s not intimidating, though, except when Aislyn glimpses the looming presence she really is. Instead she’s comforting, a big sister or best friend, Not-Normal yet reassuring in the way, amidst incomprehensible pronouncements, she echoes Daddy’s truths.

Names are magic. The people bearing New York, Manhattan, Brooklyn, we’ve met. Now Staten Island, or rather Staten Aislyn, which isn’t quite the right name. It can’t withstand the poisonous blast of the Woman’s name. Aislyn must translate that utter foreignness into something homey. Aislyn links the Woman with the powerful and yet familiar, normal, decent image of Rosie the Riveter. Rosie’s actual slogan is We Can Do It! Aislyn replaces that with I WANT YOU, a more naked statement of what Rosie and the Woman are, each in her own way.

Recruiters.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Manny, it turns out, does have an address. And a roommate, who knew Manny had an edge, but didn’t necessarily sign up for tentacle invasions and magical capitalism.

Manhattan-the-place has an edge, too. An origin myth that accurately reflects the blood and lies at its foundation, if not their exact shape. Real estate fraud and land theft, stockbrokers and slave brokers, as close to the surface as Manny’s fugued-out experiences dealing violence. The past is a double-edged sword. Useful in the moment for fighting off tentacular Karens, but not easy on the wielder. “History hurts,” indeed.

Speaking of tentacular Karens, the Woman in White is a disturbingly appropriate way for an extradimensional abomination to manifest sorta-human personality. Jemisin is writing New York versus Cthulhu, and her Cthulhu is necessarily different from Lovecraft’s—but related. In some ways her Cthulhu is Lovecraft. Or rather, uses Lovecraft types as tools. the Woman in White may think of humans as amoebae, but sees our fears and bigotries as convenient leverage to take over our reality. She’d argue, of course: she’s here to protect a hundred billion realities from the threat of our own. Do wakeful cities really threaten the multiverse, or just the eldritch version of comfortable status quo? I have my suspicions.

Either way, she’s the perfect manic pixie dream temptation for the newly-introduced avatar of Staten Island. Aislyn, unfortunately for everyone, has a bit of Lovecraft in her. Like Lovecraft, much blame can be laid on her family. I’d call Daddy cardboard if I hadn’t heard too many recordings, over the past few years, of how certain sorts of authorities talk when they think they can use “home words.” So let’s say instead that in this case, Jemisin doesn’t offer the pleasant fantasy of nuance. Some people are just terrified of what will happen if those people think they can go about living their lives. Why, they might treat the “some people” the way the “some people” treat them! Better to keep those people in their place, and avoid any weakness that might let you slip off the narrow ledge of People Who Matter.

It’s a great way to give your kid an anxiety disorder—one that’s hard on both her and her surroundings. Aislyn’s scene at the ferry terminal may be both my favorite section so far and the least comfortable. It’s clear that she’s been trained to panic at the presence and touch of people who look different from her (shades of Lovecraft’s “nautical negro”). It’s equally clear how quickly her fear shades into violence—and how vulnerable she is to sympathy from someone even superficially similar to her.

How much does the Woman in White have in common with Aislyn and her father? Better to put those cities in their place now, lest they do unto you? She certainly seems to see… something… in Aislyn, beyond vulnerability. Maybe even recognizable motivations. After all, they are both composite entities for whom the boundaries of space, time, and flesh have meaning! And who are therefore anxious to defend those boundaries.

My admittedly-outdated experience with Staten Island suggests that the Woman has its anxieties nailed. It seems like a place that holds the rest of the city at a remove, with mutual resentment. A place that isn’t quite comfortable being a city, and where enough money can convince anyone that the face-eating leopards won’t eat their faces. Manny’s neighborhood is much safer if you don’t have that money, even if equally prone to extradimensional Karens.

I haven’t even gotten into our brief introduction to Brooklyn, who wins my heart instantly by seeing saving the world as one more thing when she has to get home to her kid and sick father. I feel you, Brooklyn. And feel, from personal experience, that you’re going to be stuck doing that one more thing despite having zero room on your schedule.

Next week, we return to the heady, dangerous art of The King in Yellow with Molly Tanzer’s “Grave-Worms.” You can find it in the Cassilda’s Song anthology.

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden comes out July 26th. She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.