Let’s talk about the best of Alan Moore’s comic book work. Looking at his career, what should we designate as the capital-b Best of the Best? What ten comics would be the ultimate incarnation of Moore’s genre-bending, highly-influential comic book scripting?

I’m glad you asked!

Here’s the All-Time Alan Moore Top 10, as determined by me, the guy who has reread all of the Alan Moore comics and written about 100,000 words on the topic. All of the Alan Moore comics are worth reading (well, maybe not all of the later Extreme or Wildstorm work, but even those have something interesting going on at times), but these are the cherries on top of the ice cream sundae that is the Alan Moore oeuvre.

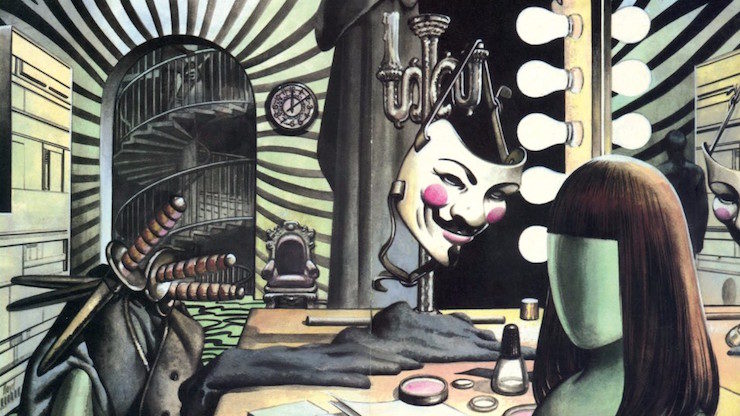

10. V for Vendetta, by Alan Moore and David Lloyd

I will still always dream of a world where the series was completed in black and white, but this challenging work remains one of Moore’s best, and Lloyd’s bleak artistry outlines the harsh conglomeration of a fascist state with manipulative media as well as anyone ever has. The title character—popularly interpreted as a rebel working against a corrupt system—may be more of a monster than some of his victims, but by giving us such a charming but merciless protagonist, Moore and Lloyd avoid simple answers to the tough moral questions.

Above all, V for Vendetta will haunt you long after you close its covers, even after the second or third or fourth read.

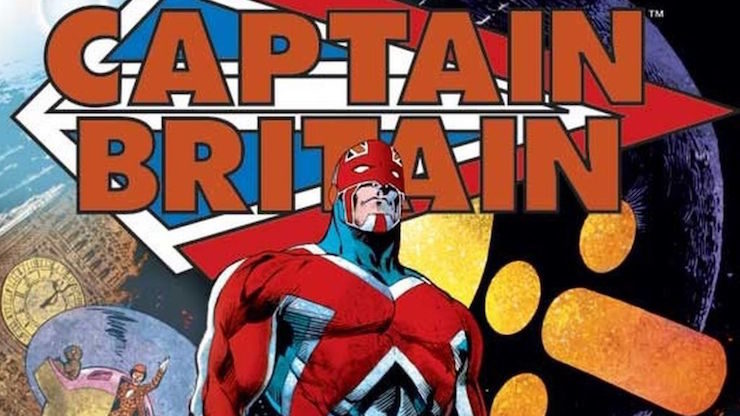

9. Captain Britain, by Alan Moore and Alan Davis

Moore’s first superhero work, now thirty years old, remains the ur-text of modern-day capes-and-cowls comic books. Too often does an incoming creative team break down and destroy a character before building him back up, but that approach was pioneered by Moore in his “Captain Britain” serials before he went on to explode the series into a widescreen action comic the likes of which the world rarely saw until the kids who grew up reading this series started writing and drawing their own comics a decade later. But this All-Time Alan Moore Top 10 isn’t based on what’s historically important. It’s based on what’s the best to read, and Moore and Davis’s “Captain Britain” comics are brutal and funny and wide-ranging and intimate.

Alan Moore didn’t just learn how to write superhero comics while plotting and scripting the adventures of Brian Braddock and friends, he demonstrated that he had massive storytelling ambitions from the start. “Captain Britain” does what so few superhero comics can: make you care about what happens while an insane, unrecognizable, imaginative world launches at your eyes.

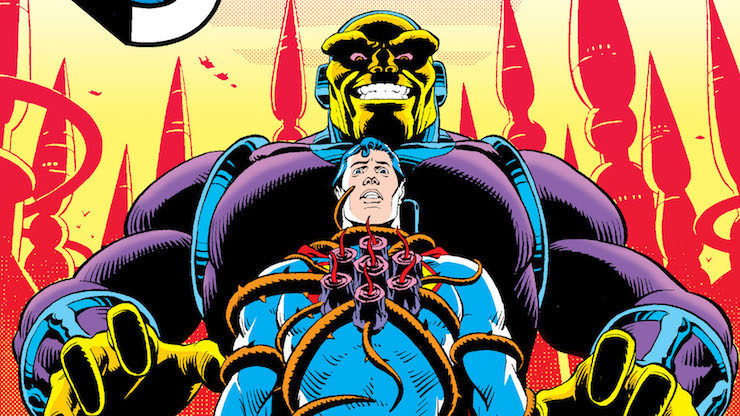

8. Superman Annual #11, by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

This is the only example of a single issue on this list of series and graphic novels, and while I thought about including “The Superman Stories” as an entry by itself—like I did with the original reread post—that would have been disingenuous. “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” the two-part story that closed out Superman’s pre-Crisis continuity just isn’t in the same league as Superman Annual #11. The former has some evocative moments, but it’s the comic book equivalent of a sinister clip show with a tragic tinge. With Dave Gibbons in Superman Annual #11, though, Moore tells perhaps the single best Superman story of all time.

In that issue, “For the Man Who Has Everything,” Superman is forced to accept reality and break free from an all-too-enticing dream of what might have been. It’s a gorgeous-looking superhero action comic that doesn’t skimp on thematic resonance. If you want a single, self-contained but powerful dose of what superhero comics can be like when they’re done well, this is a superior example.

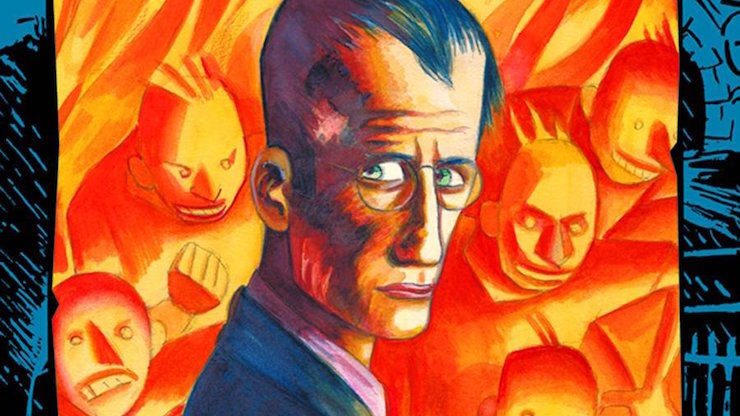

7. A Small Killing, by Alan Moore and Oscar Zárate

Part Nic Roeg nightmare and part semi-autobiographical exploration of a man who compromises his artistic integrity to produce commercial products for cash, this not-too-well-known graphic novel is one of Moore’s few completed non-genre comics, and the stunningly evocative work of Zarate would make it the belle of the alt-comics ball in any recent year.

But it’s over 20 years old, written at a time after Moore had broken away from mainstream superhero comics (and before he would return to the weird and maybe-not-really-wonderful industry as Image Comics exploded into the market). It’s easy to read A Small Killing as Moore’s commentary on his own compromises, showing a man so haunted by his childhood dreams that’s he’s forced to violently exorcise what’s left of his innocence, but even if you ignore that possibly-self-referential facet of the book, this is a great comic about a human struggling against himself and against the cruel world that would force him into that unwinnable situation. Yet it’s not bleak and hopeless. It’s alive. Like a wriggling snake sinking its teeth into your heart.

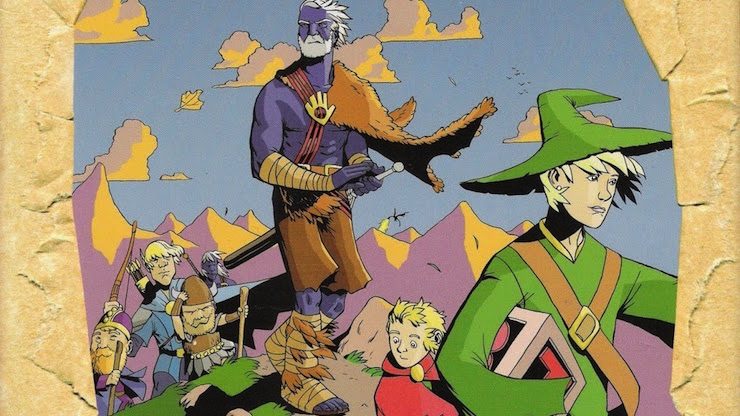

6. Smax, by Alan Moore and Zander Cannon

If you had told me when I began the Great Alan Moore Reread that Top 10, Alan Moore’s superheroes-as-cops comedy/melodrama would not crack my All-Time Alan Moore Top 10, I would have called you an evil lying liar. I mean, “Top 10” is even in the title, and that series was really good, and hyper-detailed, and how could it not be considered one of Moore’s best?

As much as I like Top 10, and I sure liked it a lot even after reading it last year, it’s not as substantial or as entertaining as the rest of the comics on this list. And it’s not as good as its own spin-off. Smax takes a different approach than Top 10—pure parody instead of pastiche plus satire—but Smax is the better comic all-around. Zander Cannon brings humor and humanity to this slapstick fantasy quest, and though Alan Moore isn’t known for his hilarity, he sure does have a wicked sense of humor that he’s not afraid to unleash. Some of his other comics are actually, um, comical, but Smax is the best of the Moore funnybooks. It’s pretty mean, too. Just the way we like ‘em back home.

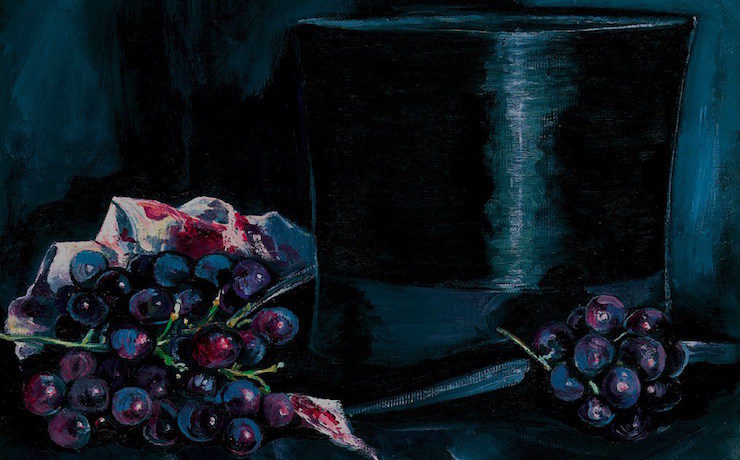

5. From Hell, by Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell

If Smax is Alan Moore at his most successfully hilarious, From Hell is Alan Moore at his most methodically serious. But it’s Moore’s attention to detail—and the disciplined work of collaborator Eddie Campbell—that makes the narrative architecture of this story as interesting as its unfolding plot.

Yes, there is literal architecture at the heart of the conspiracy within From Hell, something we learn quite a bit about thanks to a rousing bit of London travel and a guide to Freemasonry, but when I’m talking “architecture” in this comic, I’m talking about Moore’s structural poetics. From Hell is constructed from historical reference materials and panicked suppositions and the psychogeography of a specific time and a specific place when bad things happened to many people.

The book may be about Jack the Ripper and the hunt to catch the killer, but that’s only what it’s about when you turn it into a tame Hollywood movie version. That’s the surface. Beneath, Moore and Campbell give us a chilling portrait of the Victorian Age, a true work of horror that relies not on shocks and gore but on the inhuman unfolding of history.

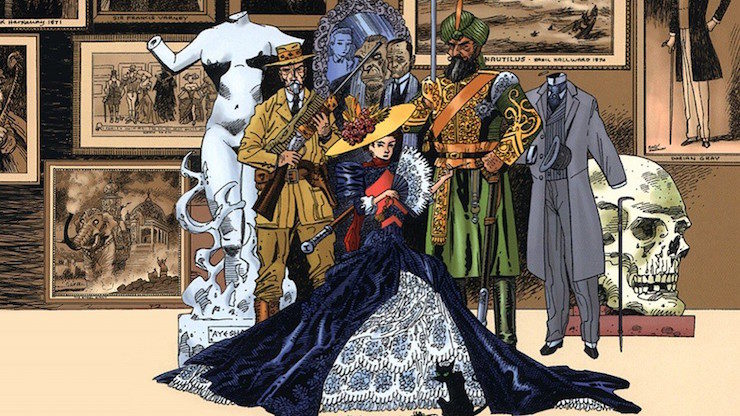

4. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, by Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill

The conceit is simple: public domain literary characters team up…for adventure! In the hands of Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill it becomes something far more than that.

Every time I reread The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen series—whether it’s the original six issues or the Mars attacks follow-up or The Black Dossier or the Harry-Potter-and-the-End-of-the-World in the three-part Century—I love it all the more.

Mina Murray is one of the great heroines in fiction, thanks to the resurrection performed by Moore and O’Neill, and she leads the ragged band of British agents against the most menacing foes. That’s all great and fun and deadly and, thanks to the carved linework of O’Neill, hideously beautiful, but it’s the literary gamesmanship that provides abundant texture to the series. Moore and O’Neill pack allusions into every page, and it takes a whole team of annotators to get most of the references, but you won’t need the cheat sheets to get the point of each chapter of the larger story. The allusions amplify and enhance, tremendously, and they add a wink and a nod to each section, but there’s still a heart and soul to these comics that tell of flawed men and women facing insurmountable obstacles with wit and vigor. And sometimes dying in the process.

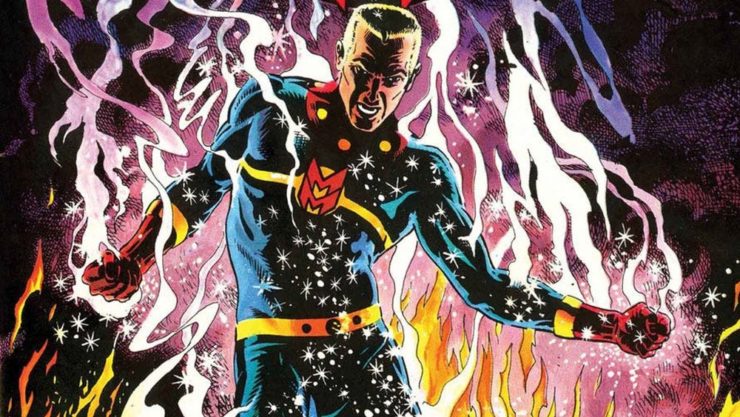

3. Marvelman, by Alan Moore, Garry Leach, Alan Davis, and Friends

If you read my original reread posts on this series, you’ll know that I stubbornly cling to calling this comic “Marvelman,” even though it became “Miracleman” once it resumed publication from Eclipse Comics in America. So my revisionist historical version of Marvelman runs up through the Eclipse issues until Moore steps away from the series, leaving it in the hands of Neil Gaiman, who never got a chance to finish what he started (to continue).

But why is Marvelman so great that it deserves a spot in the All-Time Alan Moore Top THREE?

Because this is the one that changed everything, and it’s still a heck of a comic to read, if you can find it.

The Eclipse reprints of the earlier Warrior installments of the series are gaudily colored and the word balloons and captions are too small, and the later issues—particularly the ones drawn by John Totleben—are rare and somewhat pricey for single issues. But Marvelman is worth tracking down as a milestone of the superhero genre and as a declaration by Alan Moore about what it means to enter the Modern Era of mainstream comics.

Marvelmanis based on a Captain Marvel analogue, with the cynicism of the 1980s and a dose of real-world logic smashed into its innocent shell. The opening few chapters provide a blueprint that revisionist superhero comics would follow forever after—the revelation that everything the hero thought he knew was wrong, and he may not even really be a hero to begin with—and the inky realism of Garry Leach’s drawings only helped Moore make his stand on behalf of smart, relevant, devastatingly powerful superhero comics.

The fact that everyone who came after Moore took the faux-realism and the hyper-violence of Marvelman as its primary lesson isn’t Moore’s fault. He did it right, and they just missed the point.

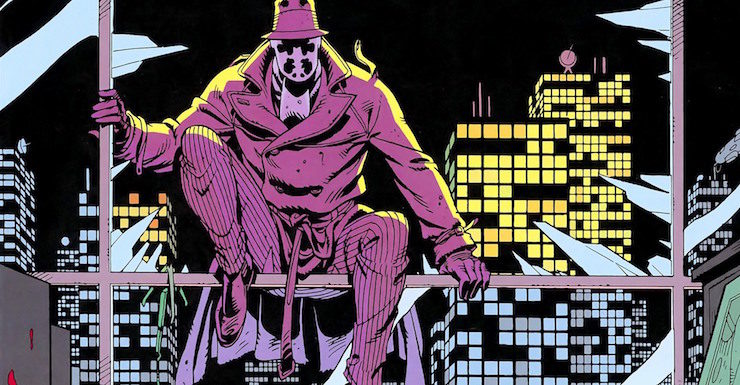

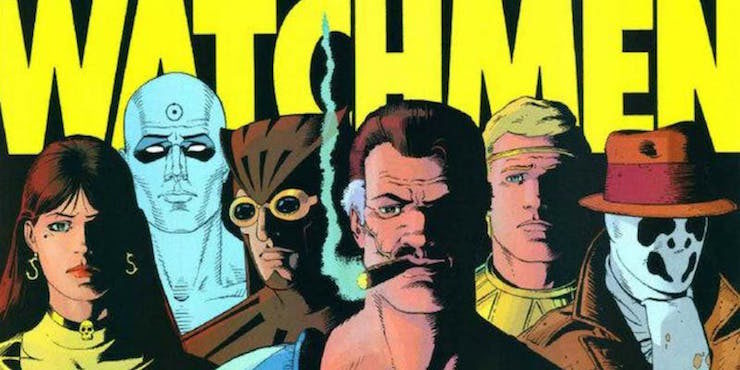

2. Watchmen, by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

Marvelman was born first, but Watchmen is the slightly younger child who learned from his sibling and turned out even more refined. The precisely designed structuralism of Watchmen can make the comic seem unnecessarily cold and self-important, until you actually sit down to read it. Watchmen’s reputation as a masterwork imparts it with a kind of aura of untouchability that’s not true to its trashy roots.

Yes, it is a well-crafted, exceedingly ambitious story with multiple narrators and multiple layers of meaning, but it’s also a comic about a mad scientist and a naked physicist and a vigilante who breaks people’s wrists. It’s about love and death and sex and violence and politics and science and war and a thirst for peace. Even when it was twelve single floppy issues, it was a big book, and nowadays you’re likely to see it in some massive Absolute Edition or regal hardcover. It deserves that treatment for the role it has played in showing that comics can do more than just tell racy stories about guys and gals in tights. But it’s really just a pulpy superhero story at its core, and it’s one of the best ever told because of how it’s told. Few comics in history surpass its achievements, and even fewer are as engaging and exciting on an aesthetic or storytelling level.

There’s only one Alan Moore comic that’s better, and it’s….

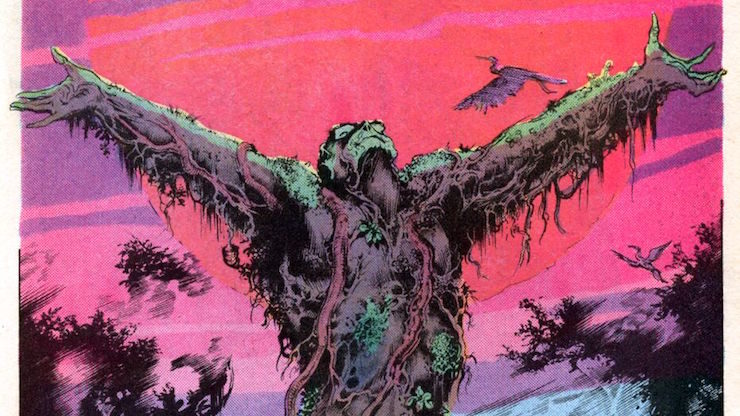

1. Swamp Thing, by Alan Moore, Steve Bissette, John Totleben, and Friends

Watchmen may be more precisely crafted and Marvelman may be more pioneering, but there’s only one correct answer to the question of “What is the Best Alan Moore Comic Book Series Ever?”

Swamp Thing, of course.

With Swamp Thing, Alan Moore trotted out his Marvelman revisionism on the much more fertile ground of American comics, and Moore’s early issues of this muck monster series show his facility at presenting characters as trite and overdone as the Justice League with a completely new point of view. In Moore’s Swamp Thing, the gods in the satellite above the Earth are terrifying and unknowable. It’s Swamp Thing’s world, and we all just walk on top of it.

Moore’s collaborators—mostly Bissette and Totleben and their former schoolmate Rick Veitch—give the comic a terrifying sense of frantic unreality, and their contributions cannot be minimized. Moore is only as good as they are, but they’re very good here and so is Moore. His second issue on the series, “The Anatomy Lesson” stands as one of the best single issue comics in the history of the medium, presenting a tragic unfolding of horrifying vegetable rebirth inside a sterile corporate laboratory. And the issues that followed—everything that makes up what would become the first Swamp Thing collected edition—present a challenging environmentalist horror action comic disguised as a monster story dressed in superheroic garb. It’s weird and wonderful and Moore tries to write the captions and dialogue like savage poetry and he succeeds.

Swamp Thing stumbles a bit at times, but for over 40 issues, Alan Moore chronicles the journey of the creature that once thought it was a man named Alec Holland, and where the monster travels to the depths of hell or into deep space, he’s always bound by his mortal love back home in the bayou. It’s messy and uneven and melodramatic and full of life and ambition and enthusiasm for comics and everything that surrounds it. It’s not pure Alan Moore, but it’s sloppy, amazing, wondrous Alan Moore and it’s the number one All-Time Best.

Originally published in January 2013 as part of The Alan Moore Reread.

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.