When I learned that Laura Dern was returning to the Jurassic-verse as Ellie Sattler in the upcoming Jurassic World: Dominion, it sent me on a spate of glorious reminiscence of how much a small group of fictional scientists meant to me.

There was a brief time, a time that shines in my memory, when weird women scientists were heroes. And I’m going to talk about them, possibly at uncomfortable length. Journey with me to a magical era of hope and high concept sci-fi, and join me in celebrating a few of coolest female scientists of the decade.

I’ve organized these women by decidedly unscientific categories; I am sure I’ve missed some of your favorites, so please sing their praises in the comments! And before we go a step further I want to shout out my beloved colleague Emmet Asher-Perrin’s essay on Real Genius, specifically for their encomium to Jordan Cochran, who is basically the baby version of the women I’m about to talk about.

Dr. Ellie Sattler — Jurassic Park (1993)

Ellie Sattler was such a blast of pure joy. From the moment we meet her in her dust-covered, head-to-toe denim, she’s funny and competent and clearly the co-leader of the dig. She also wants a kid, and is nudging Dr. Grant toward relaxing his anti-kid stance, but her feelings about motherhood don’t define her in the way they’ve seemed to define Claire Dearing in the later Jurassic Park trilogy. She doesn’t get restricted to a caretaker role in this movie, and at no point does the film itself seem to be taking a stance—after all, a different kind of film could have played out with Ellie caring for Lexie and Tim after Nedry sabotages the park, but instead she’s back at the island’s HQ, doing whatever’s necessary to get the power back on, while Allen gradually learns to be a bit more nurturing. The only instance of “men explain things to her” is Ian Malcolm explaining his expertise, chaos mathematics, at her request.

But leaving the kids aside for the moment: what’s the best scene in the movie? Ian Malcom’s water droplet demonstration? The T-Rex shaking the water cup? The T-Rex eating the lawyer? The raptor pack stalking the kids in the kitchen?

While all of these scenes are fantastic, I would argue that the film’s best scene is the one with the Triceratops shit. Remember? Soon after they start the tour, the come across a sick Triceratops. Dr. Sattler immediately goes to her aid and speaks with one of the Park’s caretakers. She surveys the plants in the area, looking for obvious toxins. And finally she dives into a mountain of Triceratops shit to check on what she’s been eating.

Doctors Grant and Malcolm stand back in horror—Grant is used to studying fossils who have been freed of basic biological functions, and Malcolm, as a mathematician, lives in a world of pure theory. But Dr. Sattler is a paleobotanist. She was the first to realize that something was strange at the Park, because she noticed flora that shouldn’t exist. And she’s ecstatic at a chance to observe an ancient herbivore and the plants it eats. She’s completely matter-of-fact at being up to her elbows in excrement, and shoos the rest of the group away to finish the tour so she can hang back and talk about plants and crap with the dinokeeper.

Maybe this doesn’t seem like such a huge deal, but it’s a woman, happily doing fieldwork—in a field where she’s regarded as one of the best in the world, per Dr. Hammond—being treated with automatic respect by all the men she’s dealing with, and not even noticing that a couple of her colleagues are grossed out because she’s too, well, engrossed.

Dr. Sarah Harding — The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997)

The sequel, The Lost World: Jurassic Park, is nowhere near on the level of the original JP. But one thing is does give us Dr. Sarah Harding, behavioral paleontologist. (It also gives us Kelly Curtis, Ian Malcolm’s fabulous daughter, but she’s not a scientist—at least not yet.)

Dr. Harding already knows the entire Jurassic Park saga, because she’s also Ian Malcolm’s girlfriend, but—and here’s where things get fun—she does not give one single fuck, because she is, as I mentioned, a behavioral paleontologist, and she jumps at the opportunity to study living dinosaurs because of course she does. Just like Ellie Sattler, she charges into her work, literally running into the middle of a herd of stegosauri to get close-up photos.

As with the first Jurassic Park, The Lost World neatly dodges the trope of the lone adult woman has to take care of a precocious kid. While Kelly and Dr. Harding clearly like each other, Kelly is Dr. Malcolm’s kid, and there’s never any sense that he expects Sarah to co-parent. At the same time, while Sarah and Ian clearly love each other, her decision to take the risk of studying the dinos was her decision, and even as the danger ramps up there’s no point where she gives up ownership of that choice.

As with Dr. Sattler and the triceratops, Dr. Harding gets one excellent setpiece that’s purely about her skill. After rescuing a baby T-Rex, she figures out that its leg is fractured. Despite the extreme danger, she takes the risk to help the animal and set its leg. She does very quick emergency surgery in their team RV, with Vince Vaughan’s Nick Van Owen acting as her assistant. And as with Dr. Sattler, she’s utterly matter-of-fact about what she’s doing. When she needs an adhesive, she simply asks Van Owen to spit his chewing gum into her palm, and uses that.

Since this is a sequel the stakes have been upped: She’s doing all of this while Mom and Dad T-Rex roar and glower through the windows. And, yes, the entire RV winds up being knocked over a cliff, their other team member Eddie Carr dies, and she, Van Owen, and Dr. Malcolm barely escape—but she finished the operation first, and confirmed that her dino parenting theories were correct.

Dr. Jo Harding — Twister (1996)

Jo Harding (no relation to Sarah as far as I know—although wouldn’t that be awesome?) doesn’t get to do quite as much on-screen science as the rest of this group, only because she also gets saddled with a lot of angst over her separation from almost-ex-husband Bill “The Extreme” Harding, and the plot hangs on the idea that Bill wants Jo to finally sign the divorce papers so he can marry his new fiancee, Melissa.

But the good thing about this film, and about Jo, is WEATHER.

Jo is a meteorologist, but what she really is, is a tornado chaser.

Jo’s initial interest in weather was sparked by her father (a theme we’ll see repeated further down the list). As a tiny child Jo watched as a tornado ripped the door off the family storm cellar and sucked her dad into the sky—the trauma seems to have given Jo an (understandable) obsession with tornadoes, but also a seemingly a belief in them as sentient, malicious entities, monsters to be understood, and when she encounter tornadoes in the film she’s transfixed—as attracted to them as she is terrified.

Jo is the head of an eccentric team of meteorologists who have utter faith in her. They’ll follow her into the worst storm in Oklahoma because they know she’s the best in the field, but also because they admire her passion for her work.

We just don’t see the science as much as I’d like, because this is a big summer blockbuster and mostly what director Jan de Bont wants to show us is cows sailing through the air and tornadoes ripping though drive-in movie screens. But even with those blockbuster elements, a lot of the dialogue is pure jargon. While Bill is shown to be kind of an adrenaline junkie, Jo is a scientist—sure she has personal reason for her obsession, but she wants to use science to understand tornadoes better. She’s the one who has finally built on Bill’s idea and created the “Dorothy” tornado tracking system, and while he’s willing to fistfight a rival tornado chaser in a parking lot for stealing the design, Jo is the one who actually figures out how to make the machine work.

Dr. Dana Scully — The X-Files (1993-2002)

And lo we come to my favorite. Dr. Dana Scully, medical doctor, PhD, Einstein re-interpreter, FBI agent, devout Catholic, alien skeptic.

The BEST. The GOAT.

But here’s the thing I want to highlight in particular. We all know that Scully’s character arc got pretty convoluted with alien abductions and pregnancies and cancer and all of that. We also know that one of the ongoing highlights of the first seasons of The X-Files was the slow-burn, deadpan flirtation between Scully and Mulder, where sometimes they were the best friends you could ever imagine, sometimes they teetered on the edge of something more romantic.

But those weren’t the best aspects of Scully, at least not for me. For me it was the moment in many, many episodes where we cut to Dana Scully, Roving Medical Examiner.

Sometimes she assists the local coroner, sometimes she flies solo, but in my favorite scenes in the show, Dana Scully snaps rubber gloves on and paws through the remains of whichever unfortunate victim necessitated the call to the FBI. A lot of the show revolves around her telling Mulder he can’t be right, while we, the audience, are pretty sure he is—but the autopsy theater is her time to shine.

And actually, one of the rare times he challenges her in the morgue is during a third season episode, “Revelations,” where Scully thinks they may have found the messiah and Mr. I Want to Believe balks at religious faith—but then again, this episode wants us to believe that the Messiah will be a white boy named “Kevin” so Mulder may have some points to make.

But, usually, once they’re in the morgue all of that drops away. Here we’re just in the quiet, semi-darkness watching Scully do something that is uniquely hers, applying all of her medical training and skepticism to the body in front of her. And like several of the other women on this list, the thing that gets to me is the sheer matter-of-factness of it. There is neither squeamishness nor gallows humor—just a woman, usually alone, working diligently. She’s doing a job that has to be done, something that’s off-putting to many (most?) people. And this is not the feminine-coded part of death—she’s not preparing a body, or mourning. She’s cutting the body up, doing a job that has always carried a certain amount of cultural taboo. She’s looking for clues to their death, looking to either corroborate or disprove her partner, looking to form her own opinions.

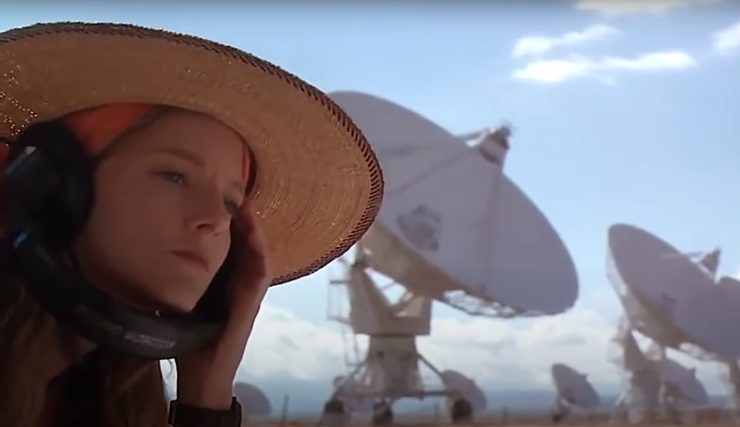

Dr. Eleanor Arroway — Contact (1997)

I’m going to call it—Dr. Ellie Arroway is the biggest nerd on this list. She spends her childhood as a ham radio operator, connecting with people around the country, and charts those connections with pins and thread on a map. If this girl had been born a few years later there would be no movie, because she’d be too busy arguing with people on BBS boards to do anything.

Given that, I also want to point out that Ellie taking her childhood hobby and using it to contact aliens is her literally going HAM.

Ellie is uncompromising, obsessive, blunt, and a little weird. She believes that there must be life somewhere out in the stars, because having such a vast universe with only the inhabitants of Earth would be a waste of space. We meet her as a weird, obsessive little kid, and then re-meet her as a weird, obsessive adult astronomer, newly arrived at Arecibo. Just like Jo Harding, she has a crew: Kent, Fish, and Willie, three men who are fairly eccentric in their own rights (though none of them rise to the heights of Phillip Seymour Hoffman ecstatic line read of “Greenage” in Twister), who trust her instincts and automatically obey her precisely because they recognize that her passion makes her the leader.

But unlike the other women on this list, Ellie Arroway has something that feels all-too-realistic to all-too-many-people: a male nemesis. Specifically David Drumlin, who is a giant in astronomy, who used to be Arroway’s mentor and who is now hellbent on sabotaging her work, undercutting her in front of colleagues, and infantilizing her by telling her that everything he does is to help her realize her promise instead of wasting time on the “nonsense” of alien contact. He gets her kicked out of Arecibo. Then he negotiates to have her lease with the Very Large Array terminated, even though she has private funding and can afford to stay. Then when she does make contact, he hijacks the project from her, making himself the liaison with the U.S. government, and even telling her to flip slides for him during a presentation she’s supposed to be leading.

Why am I spending so much time on this man, who is not the hero of the film? Because I love Arroway’s response to him, which is to not change a single fucking iota. When he yells at her, a colleague, in public, she yells right back. When he fucks with her funding, she finds new funding. When he gets her kicked out of the VLA, she keeps working, more focused than ever, which is when she finally hears the transmission from Vega that kicks off the second, more sci-fi part of the film. After he’s chosen to travel to Vega over her (more on that in a sec) she still comes to the launch as an advisor, and does her best to save him during a fundamentalist terrorist attack on the mission.

Dr. Arroway tells the truth relentlessly, and it’s fantastic to watch. When the crew first receives the schematics from Vega, she openly says she doesn’t know what they are to a panel comprised mostly of furious white men, most of whom assume it’s a weapon. (Because in science, “I don’t know” is not only a reasonable answer to a question, it’s often the best answer to a question—it means you get to find out.) The one person who supports her? Rachel Constantine, a high-level government official who, as the only Black woman in the room, has presumably had to overcome enormous obstacles to get where she is, and who steps in a few times to make sure the nerdy, hapless Arroway isn’t completely shut out.

When the Vega hopefuls are vetted, New Age theologian Palmer Joss questions her about her beliefs; she answers honestly that she bases her decisions on empirical evidence, testing, proof, and she refuses to fake a faith she doesn’t have. Her honesty costs her the mission, and she has to watch as Drumlin coughs up exactly the sort of speech they want to hear: “I would hate to see all we stand for, all we’ve fought for, for a thousand generations—all that God has blessed us with—betrayed in the final hour because we chose to send a representative who did not put our most cherished beliefs first.” But of course it also saves her life, as she’s up in the control tower when Drumlin dies in the terrorist attack. After the Vega trip, she again tells the truth, both her subjective truth of what she experienced, and the fact that she can’t prove any of it, despite National Security Council hawk Kitz screaming questions at her and gaslighting her.

And what happens? She persists, tells the truth, and leaves the hearing to find that her Palmer Joss backs her, and on top of that, thousands of people have surrounded the building to chant and hold up signs of support. More than just her own small crew, there’s a crowd of people who believe her. They’ve accepted her expertise, they admire her passion, and they’re willing to trust her theory while she puts in the work to prove it.

Which she’s able to do because Rachel Constantine, the one person in the White House who supported her, has just told Kitz to give her a grant. They both know that at least some of Dr. Arroway’s story is true—even if the public can’t know that yet—and while Kitz suggests giving her a medal, Constantine knows that the only honor the doctor will be happy with is the ability to continue her work.

***

I think it’s important to mention why these women in particular stood out in my memory. I think it’s that they’re all vindicated by the ends of their stories. Dr. Satler gets to apply her specific skill to a sick triceratops. Dr. Harding confirms her theory about dino parenting, and the other Dr. Harding watches as the Dorothy system takes flight and successfully tracks a tornado. (Both of them nearly die, but they know that the data’s been recorded, and that’s what matters.) Dr. Arroway is right about aliens—but more important she’s right about the idea that the aliens are only contacting us to help us learn. That the pursuit of knowledge is itself worthwhile, and a great adventure. And Scully’s willing to learn and adapt as she has her own alien encounters, but a lot of her core ideas are also proved correct over the course of the series—even if things go a bit wonky later on. (We’ll always have those first few seasons.) Seeing all of them come through their stories with their enthusiasm and weirdness in place, and often rewarded, gave me hope for my own idiosyncrasies. I have to theorize that I wasn’t the only one.

Now’s the part where I get serious. (You didn’t think you were getting out of this list unscathed, did you?) We’re currently living through a time when an enormous, disparate group of people are trying to drag women back into, at best, the 1950s. Everything from legal protections to societal expectations to horrific sports regulations to workplace trends to New York Times op-eds to TikTok trends to fashion—Prairie dresses? Low-rise jeans? At the same time? Really?—it’s impossible for me to look around and not see a giant fist closing around women’s lives. As ever, with everything, this fist is going to crush women of color and queer women and poor women to an even finer powder than those with the protections of money and/or whiteness.

I’m not a senator or a gynecologist or a lawyer—I’m a writer, by trade and vocation, and what I write for pay are essays and list posts about pop culture. So I’m using that to point out that thirty years ago there was a fun uptick in movies where women were just as nerdy, obsessive, competent, and smart as the men they worked with. Where they loved their careers, and where, for the most part, they were automatically respected for their expertise. Where their passion inspired kids to be excited about the futures they were going to get to have. I think it might be, uh, nice, if we could get back to this, in pop culture and in life.

Leah Schnelbach must note that none of these awesome women actually inspired them to go into science—but they have tried to do right by the fictional scientists they write about. Come talk about dino scat and corpses with them on Twitter!