I’ll be honest: it’s going to take me a long time to watch all of Archive 81.

As I have previously discussed, I am a tremendous scaredy-cat when it comes to filmed media. This is a problem, because I want to watch Archive 81, as it sits squarely in the center of one of my favorite subgenres of horror.

I’m not talking about cult stories—at least not this time. I’m talking about stories about evil, haunted, mysterious, or just plain fucked-up filmed media. Stories in which a film of some sort is an active component in the mystery, thrill, or horror, in which the fictional filmed media in question—whether it’s a dusty old reel of unknown origin or a scratchy home movie or a viral video—has an effect on the characters and the narrative that stretches into the realm of the terrifying, unsettling, or weird.

This does include found footage horror and various mixed-media, epistolary, or documentary styles of fiction, but the category is so much bigger than that… It also includes stories about lost and forbidden films, inexplicable recordings, secretive records, haunted home videos, and so much more. If it’s a story about a visual recording that spawns mystery, dread, and terror, I am here for it.

As I was white-knuckling my way into Archive 81, I realized that while I enjoy these stories in different forms—movies, TV, podcasts—the written word remains my favorite. I’ve always kept an informal list in the back of my mind, just in case anybody should ever ask me, “So, hey, creepy books about fucked up films that fuck people up—know any?” (Don’t we all keep book lists like this in our heads? Just in case?) And thinking about those books made me think about why this subgenre remains a favorite of mine, because it’s never really about the films themselves. I like movies well enough, but I’m not a cinema buff by any means, and have never been particularly interested in the culture and history of film as a medium.

But when you take a fictional film and use it to tell a dark, strange story about something else entirely, then my fascination takes hold. Here are some of the books and stories that have fed this interest over the years.

House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski

There was a time circa 2000 when everybody was reading House of Leaves, but just in case it has passed you by: it’s about a guy who finds an academic manuscript about a mysterious (and possibly nonexistent) documentary film. The film itself is about a very strange house that seems to be bigger on the inside than on the outside and changes while the owners explore it. House of Leaves is part haunted(-ish) house story, part satire of academia, part exploration of deteriorating mental health, part metatextual trickery; there is a whole lot going on here, and opinions differ on just how successful it is. I for one appreciate an interesting, ambitious mess of a tome, even if it doesn’t always work, and I have always loved the many layers of obsession, uncertainty, and perspective at work as the story unfolds.

Last Days by Adam Nevill

A documentary filmmaker is hired to make a film about an infamous cult that died in a massacre some years before. He gradually realizes that while he might be conducting the interviews and visiting the locations, he is very much not the one writing the script of how this is all going to go. Last Days has all the trappings of classic cult horror: slow-building dread, portentous nightmares, evil nuns, creepy isolated locations, outbursts of violence. It came out in 2012, before the current resurgence of true crime in pop culture, but as a lifelong true crime aficionado, part of the appeal of this story is that I know I would be all over this documentary if it were real. A mysterious, British, Satanic-flavored Wild Wild Country? Heck yeah, I would watch the Netflix series and listen to all the podcasts and read all the Reddit threads. Last Days stumbles toward the end (a perennial problem of Nevill’s; see also: The Ritual) but up until that point it does so well tapping into that instinctive desire to know more about strange, shocking, taboo tragedies, and keeps building the whole picture with compounding weirdness and increasing danger. It’s a fun, spine-tingling read.

Night Film by Marisa Pessl

This one is another interesting, ambitious mess. It’s the story of a journalist who goes poking into the mysterious death of the daughter of a legendary horror film director. Filled with article snippets, photographs, and other multimedia materials, Night Film is as much about inventing the filmography and mythology of this fictional director as it is about the mystery, which involves a boatload of tropey elements: misunderstood geniuses, coveted secret films, evil priests, sex clubs, mental hospitals, the works. I read this several years ago, and I wonder if the stuff about suspecting a famous filmmaker of terrible things might read differently today, when we have daily reminders that shitty Hollywood men are generally shitty in predatory and mundane ways, not in Gothic and preternatural ways. Overall, I like Night Film best when it’s embracing its schlocky noir roots and less when it’s archly trying to subvert them. But what I really like about the novel is how it is so very much about how the stories we weave around movies and directors can so easily turn to obsession, and how we always want to know the little nuggets of truth that make up the fiction we enjoy, especially when those truths are gruesome or strange.

***

The above three books are all tomes hefty enough to wield as weapons, so it’s time for couple of books of more normal length and a handful of shorter works.

Experimental Film by Gemma Files

By now many of you are shouting at me, with good reason, because we can’t talk about novels about creepy films without mentioning this fantastic, spooky novel. Files is both the reigning monarch of this subgenre as well as the author solely responsibly for convincing me that the entire Canadian independent film community is haunted or cursed or both. In Experimental Film, a film historian begins looking into the origin of a film she sees in snippets at a screening, which leads her to dig into the life and disappearance of a trailblazing Canadian woman filmmaker who also happened to be more than a little interested in folk tales and spiritualism. This is a wonderful example of a story in which the film itself is an active participant in the horror, starting with the sly detail that silver nitrate reels are literally dangerous (i.e., highly flammable). I love it for its depth of the history, its meditations on art and lore that has been lost over time, as well as how the layered tension between subject, filmmaker, and film critic bends and twists in fascinating ways when the subject of a film is something that bends and twists reality itself.

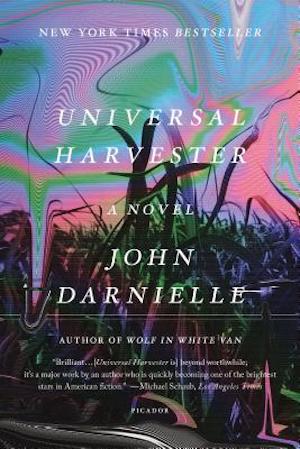

Universal Harvester by John Darnielle

In spite of its extremely misleading marketing copy, this book is neither horror nor thriller, and I suspect many readers are baffled when that’s what they expect. It is laced with a heavy sense of dread and unease, as we step into the atmospheric depression of a small-town video store in the 1990s. An employee starts investigating when customers complain about their rented movies being interrupted by inexplicable snippets of unsettling footage that appears to be about a cult. That investigation forms the scaffolding of the plot, but the book isn’t really about a cult, no more than it’s about the strange footage. It’s about grief, above trying and failing to move on from senseless tragedies, about the different ways we lose people we love, about reaching out and trying to communicate, about the way life so often provides neither explanations nor answers. Darnielle is so good at exploring how the experience of a story, in any form, can change depending on who is telling and who is listening.

***

Now let’s get into some of the shorter works, because it’s a topic that horror writers explore in short fiction to great effect.

One example is John Langan’s “Lost in the Dark” (in Ellen Datlow and Lisa Morton’s Haunted Nights anthology). This is another one that plays with our fascination for the hidden truths behind movies, as it takes the form of a reporter (“John Langan”) interviewing a horror movie director about a film that may or may not be entirely fictional. What I love about this one is how it deals with the inherent trust that we have when we sit down to watch a film, that it is either something true that happened and was recorded, or something fictional that was invented and was recorded, and foolishly assume that we always know the difference.

Another great short story is Gemma Files’ and Stephen J. Barringer’s “each thing i show you is a piece of my death,” which explores some of the same horror elements as Experimental Film, but does so in an completely different way, and hooks right into the fear that comes from learning that just because something is caught on film doesn’t mean it’s captured in any safe, tame sense of the word.

I would be remiss not to mention “Candle Cove” by Kris Straub, a classic of creepypasta for good reason. In about 1100 words of fictional message board posts, it plays with the inherent bizarreness of children’s television, the way old fears linger in the back of our minds well into adulthood, and the unreliability of memory.

Last but not least, Lost Films, edited by Max Booth III and Lori Michelle, is an entire anthology of these stories. The horrifying media in question includes secret movies of revered film auteurs (Brian Evenson’s “Lather of Flies”), childhood baptism home videos (Kristi DeMeester’s “Stag”), art school rotoscope animation (Betty Rocksteady’s “Elephants That Aren’t), the reality-warping unreturned VHS tapes of the Last Blockbuster (“The Fantastic Flying Eraser Heads” by David James Keaton), and so much more. This is one of those rare anthologies that I read through from beginning to end, because even when a story didn’t quite work for me it was still fun to see how many different directions the stories could take.

It’s this variety, I think, that keeps me coming back to this little subgenre of literature. In truth, I rarely want to see the shoddy VHS tapes or the great director’s missing last film. I’d rather imagine it all from the descriptions, from what the characters tell me, from what they don’t tell me. I love going into a story knowing that there will be another story wrapped up in it, and not one that is easy to parse or simple to put together. I love knowing that the interior story will be fractured in some way, filtered through the limitations, interpretations, and purposes of visual media. What it’s missing, how it’s damaged, how it’s been presented, who seems it, who hides it—as well as characters who don’t have the whole picture either and may never get it—all of that, when well-deployed, can add so much. And I love knowing that a story is playing with my trust in what I am being told, with my expectations about what films can do, with my understanding of why people tell some stories and erase others.

There are infinite ways for this play out, because the very nature of structuring a story around fictional media means that both author and reading are constantly splicing together the whole on multiple levels. It’s trickery, sure, but it’s trickery that author and reader agree to enjoy together, because we all go into spooky film stories knowing there is more going on than meets the eye, and we are in fact hoping it will be frightening, destabilizing, and unsettling. Films, movies, visual records in any form—these are all things that have a huge impact on our lives, shaping so much of what we see and how we interpret it. The endless ways we have of exploring that complexity leads to delightful puzzle-box stories I never get tired of reading.

Kali Wallace studied geology and earned a PhD in geophysics before she realized she enjoyed inventing imaginary worlds more than she liked researching the real one. She is the author of science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels for children, teens, and adults. Her most recent novel is the science fiction thriller Dead Space. Her short fiction has appeared in Clarkesworld, F&SF, Asimov’s, Tor.com, and other speculative fiction magazines.