In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Noted science fiction author and critic Theodore Sturgeon famously professed that “ninety percent of everything is crap.” But even if that is true, there are some places where that non-crap, excellent ten percent is concentrated—and one of those places has always been The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, or F&SF, as it is often abbreviated. And when the best of the first 20 years of that magazine was distilled down into 20 stories in a single anthology, the result was some pretty potent stuff—potent enough to have a truly profound effect on the reader.

My reading habits were largely formed by the books and magazines that my dad collected in our basement. There were two magazines he followed during my youth: Analog and Galaxy. Analog had a very strong house style, guided by the heavy editorial hand of John Campbell. The magazine featured plucky and competent heroes who faced adventures with courage and pragmatism, and solved problems largely through logic. While Galaxy, guided by H. L. Gold and Frederik Pohl during my youth, offered a more diverse mix of stories, it also focused largely on adventure and science. F&SF, on the other hand, put emotion before logic, with protagonists who were often deeply flawed, and because fantasy was in the mix, the fiction not strictly bounded by any laws of science, or even pseudo-science. The stories were often extremely powerful and evocative, forcing the reader to think and feel.

When I encountered this anthology in college, I was unfamiliar with the strain of stories it contained. Thus, I had developed no immunity that could protect me from their impact, and every tale hit home like a sledgehammer. The anthology introduced me to authors I had never encountered, and many of them, especially Alfred Bester, later become favorites. The reading choices I made afterward became broader, and I grew less enamored of the stock adventure plots I had grown up with. And I’ve revisited this anthology many times—the copy of the book I read for this review, despite having been re-glued a couple of times, is more of a pile of loose pages inside a cover than a book, tattered from years of re-reading.

About the Editors

Edward L. Ferman (born 1937) edited F&SF from 1966 to 1991. He is the son of previous editor Joseph W. Ferman. The magazine prospered under his leadership, winning four Best Magazine Hugos, and after the Best Magazine category was eliminated, he won the Best Editor Hugo three times. He also edited Best Of anthologies drawn from the magazine.

Robert P. Mills (1920-1986) was an editor and literary agent. He was managing editor of F&SF from its founding, editor from 1958 to 1962, a consulting editor in 1963, and assembled anthologies for the magazine. He also edited Venture Science Fiction for two years, and went on to a successful career as an agent.

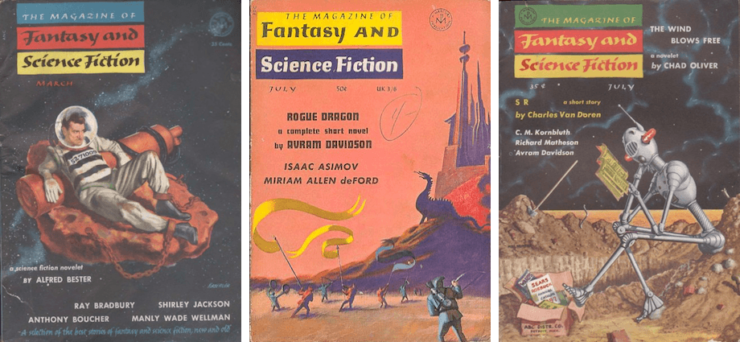

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction

Published continuously since 1949, F&SF is among the most venerable of magazines in the field, and has published well over 700 issues during this long run. The editors at its founding were Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas, with Robert P. Mills serving as managing editor. Subsequent editors included Avram Davidson, Joseph W. Ferman, Edward L. Ferman, Kristine Kathryn Rusch, Gordon Van Gelder, and C. C. Finlay. The magazine has also had many distinguished columnists over the years, most notably long-time science columnist Isaac Asimov, and its book reviewers have included Damon Knight, Alfred Bester, and Algis Budrys.

F&SF has long been known for publishing high quality, sophisticated stories, including fiction from some of the best writers in the field. Both the magazine and its content have been recognized by many awards over the years. F&SF was awarded eight Best Magazine Hugos, and its editors earned a total of six Best Editor Hugos. Over fifty stories published in the magazine have garnered either the Hugo, the Nebula, or both awards. The cover artwork for the magazine has always been distinctive and of high quality. Unlike other magazines in the field, however, it was almost exclusively published without interior illustrations.

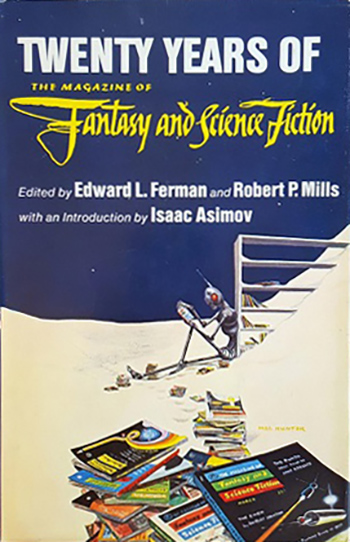

Twenty Years of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction

The book opens with an introduction from Isaac Asimov, “Forward: F&SF and I.” Asimov wrote a long-lived science column in the magazine, and in those days, because of name recognition, was quite in demand to write introductions and cover blurbs.

The first story, by Alfred Bester, was one that completely changed the way I saw science fiction. Starting with the title, “5,271,009,” it was like nothing I had ever read before. It introduces us to Solon Aquila, compelling and eccentric, exiled from Heaven for unexplained crimes, whose anguish at his exile is so powerful that if anyone sees him at an unguarded moment, it can drive them mad. That’s what happens to Jeffrey Halsyon, Aquila’s favorite artist, and Aquila sets out to rescue Halsyon from his retreat into childish fantasy. Aquila accomplishes this by allowing him to live out those immature fantasies: Halsyon experiences being the last virile man on Earth, travels back in time to relive his youth, becomes the only man who can save Earth from aliens, becomes the last man on Earth and meets the last woman, and becomes a character in a book. Each time he feels unique because of a “mysterious mutant strain in my makeup.” But each time the fantasy goes spectacularly and horribly wrong, and finally Halsyon decides to grow up and leave madness behind. I was horrified to realize that each of these stories contained plots similar to many of my favorite science fiction stories. It was clear that Halsyon was not the only one who needed to grow up—suddenly, a single story had me questioning my reading habits and my standards on what made a story a good one!

The next story, by Charles Beaumont, is “Free Dirt.” It follows a man filled with avarice, who ends up consumed by his own passions. Larry Niven’s “Becalmed in Hell,” the closest thing to a hard science fiction story in the anthology, presents an astronaut and a cyborg ship in the atmosphere of Venus, trapped when the ship’s brain can’t control the engines. In the chilling “Private—Keep Out,” by Philip MacDonald, a man runs into an old friend he had forgotten…only to find that the entire world had forgotten the friend, and might soon be forgetting him. John Anthony West’s story “Gladys’s Gregory” is a delightfully creepy tale of women fattening up their husbands; you can see the twist ending coming, but then it twists again. The Isaac Asimov story “Feminine Intuition” is well told, and its breezy style reminds me why Asimov was so popular, and so accessible. It features one of his greatest characters, robotics expert Susan Calvin. But the story is dated, as it depends on Calvin’s being unique in a mostly male workplace, and on the men being gripped with a sexist mindset that blinds them to their problem’s solution.

The next story, “That Hell-Bound Train” by Robert Bloch, is one of my favorites of all time. It follows a man who is visited by the titular hell-bound train and makes a deal with the conductor, who gives him a watch that can stop time whenever he wants. The protagonist thinks he has found a way to cheat death, but always hesitates because he might be happier later. This allows the conductor to think he has won, but the story takes a twist that becomes the best ending ever. I liked the story when I first read it, and with the passing years it has become even more meaningful to me.

“A Touch of Strange” gives us Theodore Sturgeon at his best and most empathic. A man and woman swim to an offshore rock to see their mermaid and merman paramours, but find each other instead, and learn that fantasy can’t compete with real love. In the next story, with their tongues firmly in cheek, R. Bretnor and Kris Neville give us “Gratitude Guaranteed,” the tale of a man who manipulates a department store computer to get things for free, and ends up getting more than he ever hoped for. While it is intended as humor, the story also anticipates today’s mail order culture, and I can easily imagine those items arriving at his house in boxes with familiar trademarked smiles on the side. Bruce McAllister’s “Prime-Time Teaser” gives us the moving story of a woman who survived a virus that killed all life on Earth—and how, after three years, she finally accepts the fact she is alone.

“As Long as You’re Here,” by Will Stanton, follows a couple obsessed with building the ultimate bomb shelter as they burrow deep into the Earth. Charles W. Runyon gives us “Sweet Helen,” where a trader travels to a trading station to investigate the loss of his predecessors. In a tale told from an unabashedly male gaze, he finds the women of this world have pheromones that can affect a human, and is drawn into a mating cycle that mixes passion with horror. The story sent a chill down my spine as a youngster, and still creeps me out today. In “A Final Sceptre, A Lasting Crown,” the incomparable Ray Bradbury gives us a story of the last man in Britain, where everyone else has fled to warmer climates. The story makes no logical sense, but tugs at the heartstrings nonetheless. Bruce Jay Friedman’s “Yes, We Have No Ritchard” gives us a man who has died and gone to the afterlife, only to find there is no judgement, a concept he finds infuriating.

From Philip K. Dick we get the classic tale “We Can Remember It For You Wholesale.” A man wants to travel to Mars, but can’t afford the trip, so he goes to a company that can implant memories to make him feel like he made the trip. The memory-altering company discovers he had indeed been to Mars as a secret agent, and as the story progresses, true and false memories mix until you can’t be sure which is which. The story inspired the 1990 movie Total Recall, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, and plays with some of the same science fiction tropes that Alfred Bester addressed in the tale that opened the anthology.

Fritz Leiber brings his often-zany sensibilities to “237 Talking Statues, Etc.” The son of a famous actor who filled his home with self-portraits before he died finds those portraits beginning to talk to him. Their conversation starts with anger, but becomes quite touching. The next story, “M-1,” is kind of a cartoon in prose form, written by Gahan Wilson, who in my mind will always be associated with his quirky cartoons that appeared in Playboy while I was in college. The short-short story follows investigators faced with an impossible statue that appears from nowhere. C. M. Kornbluth was always known for his satire, and “The Silly Season” is no exception; a wire service reporter who searches for quirky stories to fill the slow news days of summer finds those stories have a sinister connection. And in “The Holiday Man,” Richard Matheson follows a man to a horrifying job that explains a frequently appearing news item.

I had never heard of Robert J. Tilley before I read the story “Something Else,” and haven’t encountered his work since. But this single tale affected me deeply. A music historian and aficionado of early 20th-century jazz is shipwrecked on a deserted planet. He finds an alien creature with musical abilities, and with his clarinet, finds a deeper musical communion than he has ever experienced. The bittersweet tale ends by posing the question: when is a rescue not a rescue?

Edward L. Ferman’s “Afterword” provides a recap of F&SF’s history, and a little information on how the stories in the anthology were selected.

Final Thoughts

There is not a bad story in this anthology, and many of the stories represent the best examples of the genre. My personal favorites were the stories by Bester, Bloch, Sturgeon, Dick, and Tilley. Unfortunately, the anthology is not available in electronic format, but you can still find hardback and paperback editions if you search for them—and that search will be rewarded handsomely. For me, this anthology was a major turning point in my reading habits, opening the door to a much larger and more diverse world of fiction. F&SF has long been a venue where you can find stories of a type you won’t find anywhere else, and this anthology represents the cream of the crop from its earlier years.

And now it’s your turn to comment: What are your thoughts on the anthology, and the stories and authors it presents? And what are your thoughts on The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction? I suspect that a lot of folks who follow Tor.com have also enjoyed reading F&SF over the years.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.