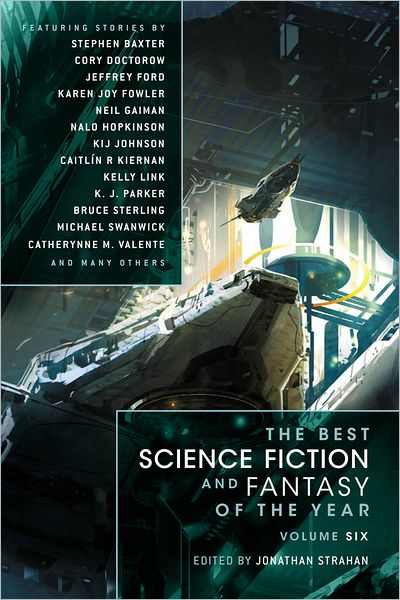

The sixth volume of Jonathan Strahan’s The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year, published by Nightshade Books, has just been released. It’s the first of the “year’s best” installments collecting work published in 2011 to come out, and the one I’ve been looking forward to the most. This year’s collection includes work by Kij Johnson, Cory Doctorow, Karen Joy Fowler, Neil Gaiman, Nalo Hopkinson, Caitlin Kiernan, and many fabulous others; several of the stories included here are now Nebula Award nominees.

Strahan’s Best of the Year books tend to be my favorite of the annual bunch (last year’s volume reviewed here), and this year’s installment was as high quality as I’ve come to expect. The book is big, nearly six hundred text-crammed pages long, and contains a comfortable mix of various different sorts of speculative fiction: science fiction, fantasy, a little science-fantasy, some stories with a touch of horror, and even a bit of urban fantasy.

That variety, in stories and authors alike, is part of what makes Strahan’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year, Volume 6 stand strong as a retrospective of 2011, as well as part of what makes it so very readable—but now, I’m just repeating what I loved about the previous volumes. Suffice to say that it’s still true and still wonderfully satisfying.

So, let’s get to the review.

Best of the Year Volume 6 has over thirty stories, including several that I’ve previously reviewed in their initial venues, like Caitlin Kiernan’s “Tidal Forces” and Nalo Hopkinson’s “Old Habits,” both of which appeared in Eclipse 4. Others I read for the first time here. While the majority of the stories are from print magazines and anthologies, online magazines like Subterranean, Clarkesworld, and Tor.com also made a good showing in Strahan’s retrospective.

The collection as a whole has a delightful coherence and unity, supported by Strahan’s careful attention to the arrangement of the stories themselves. The balance between difference and similarity from story to story throughout the book is well managed and maintains a smooth reading experience that is, nevertheless, not too smooth (and therefore boring). I was satisfied both by the stories included and the way that they were linked together in the collection—never a dull moment. The overall quality of the stories in Best of the Year Volume 6 trends toward greatness: full of strong prose and praiseworthy resonance, the stories often stuck with me after I’d finished them.

However, since there are so many stories in this collection, I won’t be discussing them all individually. Rather, I want to explore the high and low points—with the caveat that those stories that I don’t mention are all above average and thoroughly enjoyable. The high points are particularly high, and also diverse in content, style, and authorship.

Caitlin Kiernan’s “Tidal Forces” is potentially my favorite short story of the entire year, a breathtaking, emotional, frightening experience of a tale. As I said in my previous review, “This is a story that well and truly demands a second reading, and for the best possible reasons.” The imagery, the non-linear narrative, the metatextual commentary on stories, and the fabulously developed characters are all pieces of an intricate, stunning whole. The emotional resonance that “Tidal Forces” strikes is powerful and unsettling; the prose is both handsome and staggeringly effective. That Strahan has included it in his Best of the Year thrills me to no end, as it gave me an excuse to read it for the sixth (or seventh?) time.

“Younger Women” by Karen Joy Fowler is an understated tale, an urban fantasy in which a woman’s daughter brings home a vampire boyfriend, that is concerned with exploring issues of motherhood, relationships, and communication. Its domestic setting and mundane, real-seeming characters are the driving force behind the story’s eventual thematic impact, as the generational divide between the Jude, the mother, and her daughter Chloe prevents her from communicating the danger inherent in the girl’s relationship with the vampire boyfriend. The closing lines are spot-on perfect; Fowler’s prose is precise and hits hard. While the only things that “happen” in the story are dinner and a set of conversations, the movement under the surface of the narrative is immense and unsettling.

K. J. Parker’s “A Small Price to Pay for Birdsong” is unlike the other stories in a variety of ways. For one, it is only tangentially speculative; it’s not set in our world, but otherwise, it is a long exploration of one composer and professor’s relationship to his brilliant and unstable protégé, both of whom are deeply flawed and unpleasant people, that eventually results in his arranging for the protégé to be jailed and forced to write music again—but the music is never quite what it was, before. The concerns with poverty, creativity, authenticity, authorship, and choice that overlie the narrative of Parker’s tale make it ring with a subtle set of truths about making impossible decisions and the nature of betrayal. The reader is led to at once sympathize with and despise the professor, while the protégé is both immensely fun and immensely irritating, at turns playful and deadly, understanding and cruel. I hadn’t thought that a story about music composition would be so gripping and provocative, but Parker makes it so through these two characters as they play off of and around each other over a period of decades.

“The Paper Menagerie” by Ken Liu, a Nebula nominee for short story this year, is an emotionally wrenching story of prejudice, cultural bias, and “passing” that did, actually, bring tears to my eyes at the end. Another tale built on small moments and precise prose, “The Paper Menagerie” follows the narrator from his childhood to his adulthood and the eventual death of his Chinese immigrant mother. The letter he finds from her on Qingming, when the paper animals she had made for him as a child come back to life once more, is the story of her life and how she came to America, how she loved him, and how his refusal to participate in her culture or even speak to her hurt her deeply. This is another story that I would describe as breathtaking without hyperbole: the weight of the closing lines and the narrator’s revelation is crushing for the reader. The emotion is not overstated or overplayed—rather, it takes its strength from its subtlety and its power from the way the reader comes to identify with the narrator, before the letter unfolds and he is read her last words to him.

Maureen F. McHugh’s “After the Apocalypse” managed to legitimately shock me with its ending, sharply enough that I read the story again. In it, after economic collapse that causes a sort of soft apocalypse, a mother and her daughter are travelling north because they’ve heard of a refugee camp there. The story follows their travels as they meet up with a younger man who seems to like them and then find a temporary camp with soldiers handing out water and food. The mother, tired of her daughter’s inability to grow up and of being trapped in these refugee places not meant for someone like her, arranges to be smuggled out with some of the contractors and leaves her daughter with the man they’ve just met. The responses this story provokes are intense—despite my initial unwillingness, I found the mother even more sympathetic on the second read. She is a human being with needs, too, and not simply a foil for her daughter, who is old enough, she thinks, to take care of herself. “After the Apocalypse” flies in the face of conventional social structure, but that is what makes it so stunning. This story, possibly more than any “post apocalypse” tale I’ve ever read before, strikes me as getting to an unattractive but essential truth about human nature in crisis: each for themselves, each to their own. Not to mention, the prose is tight, dense, and carries the narrator’s voice supremely well—part of what makes her sympathetic. (It’s also a nice counterbalance to Fowler’s story.)

“The Book of Phoenix (Excerpted from the Great Book)” by Nnedi Okorafor is a story that I’ve read before, and enjoyed as much the second time as the first. In a world where the ends justify the means in science, the protagonist, Phoenix, is held in a facility called Tower 7. Her slow discovery, through books and the death of her only real friend, of her captivity and her desire to be free are allegorically interesting commentaries on the meaning of freedom—while the eventual destruction of the tower, allowing her and her fellow prisoners to escape, is a conflagration of joy and growth, literal and metaphorical, that allows for real freedom to come into being. The plot of the story and the characters are lovely, but Okorafor’s ability to construct a wonderful allegory out of a great story is what makes “The Book of Phoenix” one of my favorite tales in this collection.

Finally, there is another Nebula nominee, Kij Johnson’s “The Man Who Bridged the Mist.” I found this slow-moving and richly developed novella to be both satisfying and thought-provoking. The two main characters, Kit and Rasali, have one of the more complicated and striking relationships depicted in this collection. The bridge-building that drives the thematic arguments about change, social evolution, and the loss of traditional ways of life is, for all that I had thought I wouldn’t be intrigued by the technical details, remarkably fascinating—because we see it through Kit’s eyes, and he is an architect above all. His inner narrative and desires are complex and at times heart-breaking, balanced as they are against the unpredictable and equally complex ferry-pilot, Rasali. The worldbuilding is also the best of the bunch in this entire collection, to my eye—Johnson builds a strange and fantastical setting full of caustic mist-rivers and strange, monstrous fish-like creatures that live within them, while also developing a rounded, intriguing society in concert with that weirdness. There are questions left teasingly unanswered, but others are answered with careful touches of detail and exposition that never quite tip over into “noticeable” territory. Johnson’s prose supports and develops a deep, complicated story of culture and interpersonal relationships that moves at exactly the right pace—a fine story.

As for those stories that I found lackluster, only one particularly irritated me, though the others were disappointing in their ways and not, I think, suited to this Best of the Year collection. To begin, I’ll say simply that “Malak” by Peter Watts is a good story—until the end, when I frankly wanted to throw the book across the room. Watts has a tendency toward telling otherwise fabulous stories that contain a nasty kernel of unexamined misogyny, and “Malak” is no different. The story of the combat drone developing a set of ethics based in its protocols is great; it would have been on the good-story list, were it not for the ending lines, in which Watts turns the gender-neutral drone (“it”) into a “she”—after it develops “feelings” in a way, and also when we learn that it has a nuclear device in its “womb” that it’s going to destroy the command center with. So, we go from a good story about a technological device developing protocols for dealing with war to a story about a woman-object that is deadly in her reproductive capabilities. Not only is this an unnecessary little “twist,” it robbed the story of all of its thematic freight for me by reducing the otherwise salient commentary on machine intelligence to just another story where the deadly object has to become feminized, with a “womb” carrying its destructive capacity. I assume that this was probably not the intent of the pronoun shenanigans and the “womb” terminology, but I can’t for the life of me figure out what the hell it was intended to do, other than potentially humanize the machine—which also detracts from the thematic argument of the story. (I wouldn’t have been happy if we’d gotten “he” as a pronoun, either, in the last sentences.) In two words, summing up my response: goddammit, really?

The other stories that were low points for me are nowhere near as egregious; they simply aren’t cutting it. “The Invasion of Venus” by Stephen Baxter is a serviceable story that is nonetheless weighed down by didactic, potentially even pedantic dialogue that distracted me from the strengths of the story—a sort of cosmicism—and guided me instead to focus on what the characters wanted to Tell Me while talking at each other, instead. “The Onset of a Paranormal Romance” by Bruce Sterling is just plain sloppy—there are only so many times you can use the word “kinky” in one story to describe girls, lingerie, culture, etc. before I begin noticing how many times you’ve repeated it. There are other cheap prose-level mistakes that weaken this story for me, and the overall arc is shallow and unconvincing. The characters are dull and almost cartoonish, unbelievable as people. Not Sterling’s finest work, by far.

However, out of more than thirty stories, only three of them weren’t to my taste. That’s a damn good ratio. The high points of the book are particularly high, while the lows would—in some cases, at least—be acceptable in another, less awesome context.

*

I would recommend Strahan’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year, Volume 6 to any reader of the genre, as a retrospective that covers quite a lot of 2011’s ground and also as a fine collection of stories in and of itself. It more than fulfilled my expectations. Strahan has hit them all out of the park, so far, in his Best of the Year series. I look forward to next year’s installment.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic and occasional editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. Also, comics. She can be found on Twitter or her website.

I, for one, am curious about what other decent-ish* stories about “woman-objects which are deadly in their reproductive capacities” are out there

___

* decent-ish = less goofy than Species movie(s)

Wow, this review is just horrible. I won’t use the term “feminazi” ’cause it’s used by genuine misogynists, but this blatant display of feminist-extremist delusion reminds me on it nonetheless.

No clue how Ms. Mandelo can misunderstand the simple allegory of a nuke in the womb of the AI drone being compared to a baby, but I think ideological blinders are involved. It’s obvious to use “she” instead of “it” to convey the transition from a mere object to a living, intelligent being.

Tor.com would do good to get rid of this person. She’s obviously incapable to write unbiased by her radicalism.

PS: As my nick implies, I have two X chromosomes and didn’t feel offended by this story at all.

h, don’t be so harsh, the review is okay, but I kinda-sorta don’t see how “robot discovers a kind of feminine-like identity to itself, conceptualizes of its nuclear bomb compartment as womb” translates specifically into misogyny, especially given that the robot is a pretty cool

guygirl. I mean, yeah, it’s a bit disturbing, butmisogyny, really… how?

Also, I am still wondering whether reviewer indeed implies that there is a huge lot of works with that general trope in them (I can barely recall four)

You can add an XY who wasn’t bothered by that either. More bothered by people worrying about word usage than high-tech perpetual war.