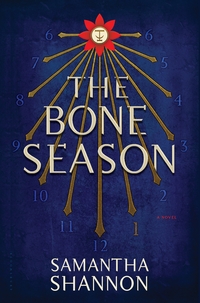

Take a look at this extended excerpt for The Bone Season by Samantha Shannon, out on August 20 from Bloomsbury. And check out the book’s Facebook page while you’re at it!:

It is the year 2059. Several major world cities are under the control of a security force called Scion. Paige Mahoney works in the criminal underworld of Scion London, part of a secret cell known as the Seven Seals. The work she does is unusual: scouting for information by breaking into others’ minds. Paige is a dreamwalker, a rare kind of clairvoyant, and in this world, the voyants commit treason simply by breathing.

But when Paige is captured and arrested, she encounters a power more sinister even than Scion. The voyant prison is a separate city—Oxford, erased from the map two centuries ago and now controlled by a powerful, otherworldly race. These creatures, the Rephaim, value the voyants highly—as soldiers in their army.

Paige is assigned to a Rephaite keeper, Warden, who will be in charge of her care and training. He is her master. Her natural enemy. But if she wants to regain her freedom, Paige will have to learn something of his mind and his own mysterious motives.

1

The Curse

I like to imagine there were more of us in the beginning. Not many, I suppose. But more than there are now.

We are the minority the world does not accept. Not outside of fantasy, and even that’s blacklisted. We look like everyone else. Sometimes we act like everyone else. In many ways, we are like everyone else. We are everywhere, on every street. We live in a way you might consider normal, provided you don’t look too hard.

Not all of us know what we are. Some of us die without ever knowing. Some of us know, and we never get caught. But we’re out there.

Trust me.

I had lived in that part of London that used to be called Islington since I was eight. I attended a private school for girls, leaving at sixteen to work. That was in the year 2056. AS 127, if you use the Scion calendar. It was expected of young men and women to scratch out a living wherever they could, which was usually behind a counter of one sort or another. There were plenty of jobs in the service industry. My father thought I would lead a simple life; that I was bright but unambitious, complacent with whatever work life threw at me.

My father, as usual, was wrong.

From the age of sixteen I had worked in the criminal underworld of Scion London—SciLo, as we called it on the streets. I worked among ruthless gangs of voyants, all willing to floor each other to survive. All part of a citadel-wide syndicate headed by the Underlord. Pushed to the edge of society, we were forced into crime to prosper. And so we became more hated. We made the stories true.

I had my little place in the chaos. I was a mollisher, the protégée of a mime-lord. My boss was a man named Jaxon Hall, the mimelord responsible for the I-4 area. There were six of us in his direct employ. We called ourselves the Seven Seals.

I couldn’t tell my father. He thought I was an assistant at an oxygen bar, a badly paid but legal occupation. It was an easy lie. He wouldn’t have understood if I’d told him why I spent my time with criminals. He didn’t know that I belonged with them. More than I belonged with him.

I was nineteen years old the day my life changed. Mine was a familiar name on the streets by that time. After a tough week at the black market, I’d planned to spend the weekend with my father. Jax didn’t twig why I needed time off—for him, there was nothing and no one outside the syndicate—but he didn’t have a family like I did. Not a living family, anyway. And although my father and I had never been close, I still felt I should keep in touch. A dinner here, a phone call there, a present at Novembertide. The only hitch was his endless list of questions. What job did I have? Who were my friends? Where was I living?

I couldn’t answer. The truth was dangerous. He might have sent me to Tower Hill himself if he’d known what I really did. Maybe I should have told him the truth. Maybe it would have killed him. Either way, I didn’t regret joining the syndicate. My line of work was dishonest, but it paid. And as Jax always said, better an outlaw than a stiff.

It was raining that day. My last day at work.

A life-support machine kept my vitals ticking over. I looked dead, and in a way I was: my spirit was detached, in part, from my body. It was a crime for which I could have faced the gallows.

I said I worked in the syndicate. Let me clarify. I was a hacker of sorts. Not a mind reader, exactly; more a mind radar, in tune with the workings of the æther. I could sense the nuances of dreamscapes and rogue spirits. Things outside myself. Things the average voyant wouldn’t feel.

Jax used me as a surveillance tool. My job was to keep track of ethereal activity in his section. He would often have me check out other voyants, see if they were hiding anything. At first it had just been people in the room—people I could see and hear and touch— but soon he realized I could go further than that. I could sense things happening elsewhere: a voyant walking down the street, a gathering of spirits in the Garden. So long as I had life support, I could pick up on the æther within a mile radius of Seven Dials. So if he needed someone to dish the dirt on what was happening in I-4, you could bet your broads Jaxon would call yours truly. He said I had potential to go further, but Nick refused to let me try. We didn’t know what it would do to me.

All clairvoyance was prohibited, of course, but the kind that made money was downright sin. They had a special term for it: mime-crime. Communication with the spirit world, especially for financial gain. It was mime-crime that the syndicate was built on.

Cash-in-hand clairvoyance was rife among those who couldn’t get into a gang. We called it busking. Scion called it treason. The official method of execution for such crimes was nitrogen asphyxiation, marketed under the brand name NiteKind. I still remember the headlines: PAINLESS PUNISHMENT: SCION’S LATEST MIRACLE. They said it was like going to sleep, like taking a pill. There were still public hangings, and the odd bit of torture for high treason.

I committed high treason just by breathing.

But back to that day. Jaxon had wired me up to life support and sent me out to reconnoiter the section. I’d been closing in on a local mind, a frequent visitor to Section 4. I’d tried my best to see his memories, but something had always stopped me. This dreamscape was unlike anything I’d ever encountered. Even Jax was stumped. From the layering of defense mechanisms I would have said its owner was several thousand years old, but that couldn’t be it. This was something different.

Jax was a suspicious man. By rights a new clairvoyant in his section should have announced himself to him within forty-eight hours. He said another gang must be involved, but none of the I-4 lot had the experience to block my scouting. None of them knew I could do it. It wasn’t Didion Waite, who headed the second-largest gang in the area. It wasn’t the starving buskers that frequented Dials. It wasn’t the territorial mime-lords that specialized in ethereal larceny. This was something else.

Hundreds of minds passed me, flashing silver in the dark. They moved through the streets quickly, like their owners. I didn’t recognize these people. I couldn’t see their faces; just the barest edges of their minds.

I wasn’t in Dials now. My perception was further north, though I couldn’t pin down where. I followed the familiar sense of danger. The stranger’s mind was close. It drew me through the æther like a glym jack with a lantern, darting over and under the other minds. Moving fast, as if the stranger sensed me. As if he was trying to run.

I shouldn’t follow this light. I didn’t know where it would lead me, and I’d already gone too far from Seven Dials.

Jaxon told you to find him. The thought was distant. He’ll be angry. I pressed ahead, moving faster than I ever could in my body. I pulled against the restraints of my physical location. I could make out the rogue mind now. Not silver, like the others: no, this was dark and cold, a mind of ice and stone. I shot toward it. He was so, so close . . . I couldn’t lose him now . . .

Then the æther trembled around me and, in a heartbeat, he was gone. The stranger’s mind was out of reach again.

Someone shook my body.

My silver cord—the link between my body and my spirit—was extremely sensitive. It was what allowed me to sense dreamscapes at a distance. It could also snap me back into my skin. When I opened my eyes, Dani was waving a penlight over my face. “Pupil response,” she said to herself. “Good.”

Danica. Our resident genius, second only to Jax in intellect. She was three years older than me and had all the charm and sensitivity of a sucker punch. Nick classified her as a sociopath when she was first employed. Jax said it was just her personality.

“Rise and shine, Dreamer.” She slapped my cheek. “Welcome back to meatspace.”

The slap stung: a good, if unpleasant sign. I reached up to unfasten my oxygen mask.

The dark glint of the den came into focus. Jax’s crib was a secret cave of contraband: forbidden films, music, and books, all crammed together on dust-thickened shelves. There was a collection of penny dreadfuls, the kind you could pick up from the Garden on weekends, and a stack of saddle-stapled pamphlets. This was the only place in the world where I could read and watch and do whatever I liked.

“You shouldn’t wake me like that,” I said. She knew the rules. “How long was I there for?”

“Where?”

“Where do you think?”

Dani snapped her fingers. “Right, of course—the æther. Sorry. Wasn’t keeping track.”

Unlikely. Dani never lost track.

I checked the blue Nixie timer on the machine. Dani had made it herself. She called it the Dead Voyant Sustainment System, or DVS2. It monitored and controlled my life functions when I sensed the æther at long range. My heart dropped when I saw the digits.

“Fifty-seven minutes.” I rubbed my temples. “You let me stay in the æther for an hour?”

“Maybe.”

“An entire hour?”

“Orders are orders. Jax said he wanted you to crack this mystery mind by dusk. Have you done it?”

“I tried.”

“Which means you failed. No bonus for you.” She gulped down her espresso. “Still can’t believe you lost Anne Naylor.”

Trust her to bring that up. A few days before I’d been sent to the auction house to reclaim a spirit that rightfully belonged to Jax: Anne Naylor, the famous ghost of Farringdon. I’d been outbid.

“We were never going to get Naylor,” I said. “Didion wouldn’t let that gavel fall, not after last time.”

“Whatever you say. Don’t know what Jax would have done with a poltergeist, anyway.” Dani looked at me. “He says he’s given you the weekend off. How’d you swing that?”

“Psychological reasons.”

“What does that mean?”

“It means you and your contraptions are driving me mad.”

She threw her empty cup at me. “I take care of you, urchin. My contraptions can’t run themselves. I could just walk out of here for my lunch break and let your sad excuse for a brain dry up.”

“It could have dried up.”

“Cry me a river. You know the drill: Jax gives the orders, we comply, we get our flatches. Go and work for Hector if you don’t like it.”

Touché.

With a sniff, Dani handed me my beaten leather boots. I pulled them on. “Where is everyone?”

“Eliza’s asleep. She had an episode.”

We only said episode when one of us had a near-fatal encounter, which in Eliza’s case was an unsolicited possession. I glanced at the door to her painting room. “Is she all right?”

“She’ll sleep it off.”

“I assume Nick checked on her.”

“I called him. He’s still at Chat’s with Jax. He said he’d drive you to your dad’s at five-thirty.”

Chateline’s was one of the only places we could eat out, a classy bar-and-grill in Neal’s Yard. The owner made a deal with us: we tipped him well, he didn’t tell the Vigiles what we were. His tip cost more than the meal, but it was worth it for a night out.

“So he’s late,” I said.

“Must have been held up.”

Dani reached for her phone. “Don’t bother.” I tucked my hair into my hat. “I’d hate to interrupt their huddle.”

“You can’t go by train.”

“I can, actually.”

“Your funeral.”

“I’ll be fine. The line hasn’t been checked for weeks.” I stood. “Breakfast on Monday?”

“Maybe. Might owe the beast some overtime.” She glanced at the clock. “You’d better go. It’s nearly six.”

She was right. I had less than ten minutes to reach the station. I grabbed my jacket and ran for the door, calling a quick “Hi, Pieter” to the spirit in the corner. It glowed in response: a soft, bored glow. I didn’t see that sparkle, but I felt it. Pieter was depressed again. Being dead sometimes got to him.

There was a set way of doing things with spirits, at least in our section. Take Pieter, one of our spirit aides—a muse, if you want to get technical. Eliza would let him possess her, working in slots of about three hours a day, during which time she would paint a masterpiece. When she was done, I’d run down to the Garden and flog it to unwary art collectors. Pieter was temperamental, mind. Sometimes we’d go months without a picture.

A den like ours was no place for ethics. It happens when you force a minority underground. It happens when the world is cruel. There was nothing to do but get on with it. Try and survive, to make a bit of cash. To prosper in the shadow of the Westminster Archon.

My job—my life—was based at Seven Dials. According to Scion’s unique urban division system, it lay in I Cohort, Section 4, or I-4. It was built around a pillar on a junction close to Covent Garden’s black market. On this pillar there were six sundials.

Each section had its own mime-lord or mime-queen. Together they formed the Unnatural Assembly, which claimed to govern the syndicate, but they all did as they pleased in their own sections. Dials was in the central cohort, where the syndicate was strongest. That’s why Jax chose it. That’s why we stayed. Nick was the only one with his own crib, farther north in Marylebone. We used his place for emergencies only. In the three years I’d worked for Jaxon there had only been one emergency, when the NVD had raided Dials for any hint of clairvoyance. A courier tipped us off about two hours before the raid. We were able to clear out in half that time.

It was wet and cold outside. A typical March evening. I sensed spirits. Dials was a slum in pre-Scion days, and a host of miserable souls still drifted around the pillar, waiting for a new purpose. I called a spool of them to my side. Some protection always came in handy.

Scion was the last word in amaurotic security. Any reference to an afterlife was forbidden. Frank Weaver thought we were unnatural, and like the many Grand Inquisitors before him, he’d taught the rest of London to abhor us. Unless it was essential, we went outside only during safe hours. That was when the NVD slept, and the Sunlight Vigilance Division took control. SVD officers weren’t voyant. They weren’t permitted to show the same brutality as their nocturnal counterparts. Not in public, anyway.

The NVD were different. Clairvoyants in uniform. Bound to serve for thirty years before being euthanized. A diabolical pact, some said, but it gave them a thirty-year guarantee of a comfortable life. Most voyants weren’t that lucky.

London had so much death in its history, it was hard to find a spot without spirits. They formed a safety net. Still, you had to hope the ones you got were good. If you used a frail ghost, it would only stun an assailant for a few seconds. Spirits that lived violent lives were best. That’s why certain spirits sold so well on the black market. Jack the Ripper would have gone for millions if anyone could find him. Some still swore the Ripper was Edward VII—the fallen prince, the Bloody King. Scion said he was the very first clairvoyant, but I’d never believed it. I preferred to think we’d always been there.

It was getting dark outside. The sky was sunset gold, the moon a smirk of white. Below it stood the citadel. The Two Brewers, the oxygen bar across the street, was packed with amaurotics. Normal people. They were said by voyants to be afflicted with amaurosis, just as they said we were afflicted with clairvoyance. Rotties, they were sometimes called.

I’d never liked that word. It made them sound putrid. A tad hypocritical, as we were the ones that conversed with the dead.

I buttoned my jacket and tugged the peak of my cap over my eyes. Head down, eyes open. That was the law by which I abided. Not the laws of Scion.

“Fortune for a bob. Just a bob, ma’am! Best oracle in London, ma’am, I promise you. A bit for a poor busker?”

The voice belonged to a thin man, huddled in an equally thin jacket. I hadn’t seen a busker for a while. It was rare in the central cohort, where most voyants were part of the syndicate. I read his aura. This one wasn’t an oracle at all, but a soothsayer; a very stupid soothsayer—the mime-lords spat on beggars. I made straight for him. “What the hell do you think you’re doing?” I grabbed him by the collar. “Are you off the cot?”

“Please, miss. I’m starved,” he said, his voice rough with dehydration. He had the facial twitches of an oxygen addict. “I got no push. Don’t tell the Binder, miss. I just wanted—”

“Then get out of here.” I pressed a few notes into his hand. “I don’t care where you go—just get off the street. Get a doss. And if you have to busk tomorrow, do it in VI Cohort. Not here. Got it?”

“Bless you, miss.”

He gathered his meager possessions, one of which was a glass ball. Cheaper than crystal. I watched him run off, heading for Soho.

Poor man. If he wasted that money in an oxygen bar, he’d be back on the streets in no time. Plenty of people did it: wired themselves up to a cannula and sucked up flavored air for hours on end. It was the only legal high in the citadel. Whatever he did, that busker was desperate. Maybe he’d been kicked out of the syndicate, or rejected by his family. I wouldn’t ask.

No one asked.

Station I-4B was usually busy. Amaurotics didn’t mind the trains. They had no auras to give them away. Most voyants avoided public transport, but sometimes it was safer on the trains than on the streets. The NVD were stretched thin across the citadel. Spot checks were uncommon.

There were six sections in each of the six cohorts. If you wanted to leave your section, especially at night, you needed a travel permit and a stroke of good luck. Underguards were deployed after dark. A subdivision of the Night Vigilance Division, they were sighted voyants with the standard life guarantee. They served the state to stay alive.

I’d never considered working for Scion. Voyants could be cruel to each other—I could sympathize a little with those who turned on their own—but I still felt a sense of affinity with them. I could certainly never arrest one. Still, sometimes, when I’d worked hard for two weeks and Jax forgot to pay me, I was tempted.

I scanned my documents with two minutes to spare. Once I was past the barriers, I released my spool. Spirits didn’t like to be taken too far from their haunts, and they wouldn’t help me if I forced them.

My head was pounding. Whatever medicine Dani had been pumping through my veins was wearing off. An hour in the æther . . . Jaxon really was pushing my limits.

On the platform, a luminous green Nixie displayed the train schedule; otherwise there was little light. The prerecorded voice of Scarlett Burnish drifted through the speakers.

“This train calls all stations within I Cohort, Section 4, northbound. Please have your cards ready for inspection. Observe the safety screens for this evening’s bulletins. Thank you, and have a pleasant evening.”

I wasn’t having a pleasant evening at all. I hadn’t eaten since dawn. Jax only gave me a lunch break if he was in a very good mood, which was about as rare as blue apples.

A new message came to the safety screens. RDT: RADIESTHESIC DETECTION TECHNOLOGY. The other commuters took no notice. This advertisement ran all the time.

“In a citadel as populous as London, it’s common to think you might be traveling alongside an unnatural individual.” A dumbshow of silhouettes appeared on the screen, each representing a denizen. One turned red. “The SciSORS facility is now trialling the RDT Senshield at the Paddington Terminal complex, as well as in the Archon. By 2061, we aim to have Senshield installed in eighty percent of stations in the central cohort, allowing us to reduce the employment of unnatural police in the Underground. Visit Paddington, or ask an SVD officer for more information.”

The adverts moved on, but it played on my mind. RDT was the biggest threat to voyant society in the citadel. According to Scion, it could detect aura at up to twenty feet. If there wasn’t a major delay to their plans, we’d be forced into lockdown by 2061. Typical of the mime-lords, none of them had come up with a solution. They’d just squabbled. And squabbled. And squabbled about their squabbles.

Auras vibrated on the street above me. I was a tuning fork, humming with their energy. For want of a distraction, I thumbed my ID. It bore my picture, name, address, fingerprints, birthplace, and occupation. Miss Paige E. Mahoney, naturalized resident of I-5. Born in Ireland in 2040. Moved to London in 2048 under special circumstances. Employed at an oxygen bar in I-4, hence the travel permit. Blond. Gray eyes. Five foot nine. No distinctive features but dark lips, probably caused by smoking.

I’d never smoked in my life.

A moist hand grabbed my wrist. I started.

“You owe me an apology.”

I glared up at a dark-haired man in a bowler and a dirty white cravat. I should have recognized him just from his stink: Haymarket Hector, one of our less hygienic rivals. He always smelled like a sewer. Sadly, he was also the Underlord, head honcho of the syndicate. They called his turf the Devil’s Acre.

“We won the game. Fair and square.” I pulled my arm free. “Haven’t you got something to do, Hector? Cleaning your teeth would be a good start.”

“Perhaps you should clean up your game, little macer. And learn some respect for your Underlord.”

“I’m no cheat.”

“Oh, I think you are.” He kept his voice low. “Whatever airs and graces that mime-lord of yours puts on, all seven of you are nasty cheats and liars. I hear tell you’re the downiest on the black market, my dear Dreamer. But you’ll disappear.” He touched my cheek with one finger. “They all disappear in the end.”

“So will you.”

“We’ll see. Soon.” He breathed his next words against my ear: “Have a very safe ride home, dollymop.” He vanished into the exit tunnel.

I had to watch my step around Hector. As Underlord he had no real power over the other mime-lords—his only role was to convene meetings—but he had a lot of followers. He’d been sore since my gang had beaten his lackeys at tarocchi, two days before the Naylor auction. Hector’s people didn’t like it when they lost. Jaxon didn’t help, riling them. Most of my gang had avoided being green-lit, largely by staying out of their way, but Jax and I were too defiant. The Pale Dreamer—my name on the streets—was somewhere on their hit list. If they ever cornered me, I was dead.

The train arrived a minute late. I dropped into a vacant seat. There was only one other person in the carriage: a man reading the Daily Descendant. He was voyant, a medium. I tensed. Jax was not without enemies, and plenty of voyants knew me as his mollisher. They also knew I sold art that couldn’t possibly have been painted by the real Pieter Claesz.

I took out my standard-issue data pad and selected my favorite legal novel. Without a spool to protect me, the only real security I had was to look as normal and amaurotic as possible.

As I flicked through the pages, I kept one eye on the man. I could tell I was on his radar, but neither of us spoke. As he hadn’t already grabbed me by the neck and beaten me senseless, I guessed he probably wasn’t a freshly duped art enthusiast.

I risked a glance at his copy of the Descendant, the only broadsheet still mass-produced on paper. Paper was too easy to misuse; data pads meant we could download only what little media had been approved by the censor. The typical news glowered back at me. Two young men hanged for high treason, a suspicious emporium closed down in Section 3. There was a long article rejecting the “unnatural” notion that Britain was politically isolated. The journalist called Scion “an empire in embryo.” They’d been saying that for as long as I could remember. If Scion was still an embryo, I sure as hell didn’t want to be there when it burst out of the womb.

Almost two centuries had passed since Scion arrived. It was established in response to a perceived threat to the empire. The epidemic, they called it—an epidemic of clairvoyance. The official date was 1901, when they pinned five terrible murders on Edward VII. They claimed the Bloody King had opened a door that could never be shut, that he’d brought the plague of clairvoyance upon the world, and that his followers were everywhere, breeding and killing, drawing their power from a source of great evil.

What followed was Scion, a republic built to destroy the sickness. Over the next fifty years it had become a voyant-hunting machine, with every major policy based around unnaturals. Murders were always committed by unnaturals. Random violence, theft, rape, arson—they all happened because of unnaturals. Over the years, the voyant syndicate had developed in the citadel, formed an organized underworld, and offered a haven for clairvoyants. Since then Scion had worked even harder to root us out.

Once they installed RDT, the syndicate would fall apart and Scion would become all-seeing. We had two years to do something about it, but with Hector as Underlord, I couldn’t see that we would. His reign had brought nothing but corruption.

The train went past three stops without incident. I’d just finished the chapter when the lights went out and the train came to a halt. I realized what was happening a split second before the other passenger did. He sat up very straight in his seat.

“They’re going to search the train.”

I tried to speak, to confirm his fear, but my tongue felt like a piece of folded cloth.

I switched off my data pad. A door opened in the wall of the tunnel. The Nixie display in the carriage clicked to SECURITY ALERT. I knew what was coming: two Underguards on their rounds. There was always a boss, usually a medium. I’d never experienced a spot check before, but I knew few voyants got away from them.

My heart dashed against my chest. I looked at the other passenger, trying to measure his reaction. He was a medium, though not a particularly powerful one. I could never quite put a finger on how I could tell, my antennae just perked up in a certain way.

“We have to get out of this train.” He rose to his feet. “What are you, love? An oracle?”

I didn’t speak.

“I know you’re voyant.” He pulled at the handle of the door. “Come on, love, don’t just sit there. There must be a way out of here.” He wiped his brow with his sleeve. “Of all the days for a spot check—the one day—”

I didn’t move. There was no way to get out of this. The windows were toughened, the doors safety-locked—and we were out of time. Two torch beams shone into the carriage.

I held very still. Underguards. They must have detected a certain number of voyants in the carriage, or they wouldn’t have killed the lights. I knew they could see our auras, but they’d want to find out exactly what kind of voyants we were.

They were in the carriage. A summoner and a medium. The train carried on moving, but the lights didn’t come on. They went to the man first.

“Name?”

He straightened. “Linwood.”

“Reason for travel?”

“I was visiting my daughter.”

“Visiting your daughter. Sure you’re not on your way to a séance, medium?”

These two wanted a fight.

“I have the necessary documents from the hospital. She’s very ill,” Linwood said. “I’m allowed to see her every week.”

“You won’t be allowed to see her at all if you open your trap again.” He turned to bark at me: “You. Where’s your card?”

I pulled it from my pocket.

“And your travel permit?”

I handed it over. He paused to read it.

“You work in Section 4?”

“Yes.”

“Who issued this permit?”

“Bill Bunbury, my supervisor.”

“I see. But I need to see something else.” He angled his torch into my eyes. “Hold still.”

I didn’t flinch.

“No spirit sight,” he observed. “You must be an oracle. Now that’s something I haven’t heard of for a while.”

“I haven’t seen an oracle with tits since the forties,” said the other Underguard. “They’re going to love this one.”

His superior smiled. He had one coloboma in each eye, a mark of permanent spirit sight.

“You’re about to make me very rich, young lady,” he said to me. “Just let me double-check those eyes.”

“I’m not an oracle,” I said.

“Of course you’re not. Now shut your mouth and open up those shiners.”

Most voyants thought I was an oracle. Easy mistake. The auras were similar—the same color, in fact.

The guard forced my left eye open with his fingers. As he examined my pupils with a slit light, searching for the missing colobomata, the other passenger made a break for the open door. There was a tremor as he hurled a spirit—his guardian angel—at the Underguards. The backup shrieked as the angel crunched into him, scrambling his senses like a whisk through soft eggs.

Underguard 1 was too fast. Before anyone could move, he’d summoned a spool of poltergeists.

“Don’t move, medium.”

Linwood stared him down. He was a small man in his forties, thin but wiry, with brown hair graying at the temples. I couldn’t see the ’geists—or much else, thanks to the slit light—but they were making me too weak to move. I counted three. I’d never seen anyone control one poltergeist, let alone three. Cold sweat broke out at the back of my neck.

As the angel pivoted for a second attack, the poltergeists began to circle the Underguard. “Come with us quietly, medium,” he said, “and we’ll ask our bosses not to torture you.”

“Do your worst, gentlemen.” Linwood raised a hand. “I fear no man with angels at my side.”

“That’s what they all say, Mr. Linwood. They tend to forget that when they see the Tower.”

Linwood flung his angel down the carriage. I couldn’t see the collision, but it scalded all my senses to the quick. I forced myself to stand. The presence of three poltergeists was sapping my energy. Linwood was a tough talker, but I knew he could feel them; he was struggling to fortify his angel. While the summoner controlled the poltergeists, Underguard 2 was reciting the threnody: a series of words that compelled spirits to die completely, sending them to a realm beyond the reach of voyants. The angel trembled. They’d need to know its full name to banish it, but so long as one of them kept chanting, the angel would be too weak to protect its host.

Blood pounded in my ears. My throat was tight, my fingers numb. If I stood aside, we’d both be detained. I saw myself in the Tower, being tortured, at the gallows . . .

I would not die today.

As the poltergeists converged on Linwood, something happened to my vision. I homed in on the Underguards. Their minds throbbed close to mine, two pulsing rings of energy. I heard my body hit the ground.

I only intended to disorient them, give myself time to get away. I had the element of surprise. They’d overlooked me. Oracles needed a spool to be dangerous.

I didn’t.

A black tide of fear overwhelmed me. My spirit flew right out of my body, straight into Underguard 1. Before I knew what I was doing, I’d crashed into his dreamscape. Not just against it—into it, through it. I hurled his spirit out into the æther, leaving his body empty. Before his crony could draw breath, he met the same fate.

My spirit snapped back into my skin. Pain exploded behind my eyes. I’d never felt pain like it in my life; it was knives through my skull, fire in the very tissue of my brain, so hot I couldn’t see or move or think. I was dimly aware of the sticky carriage floor against my cheek. Whatever I’d just done, I wasn’t going to do it again in a hurry.

The train rocked. It must be close to the next station. I pushed my weight onto my elbows, my muscles trembling with the effort.

“Mr. Linwood?”

No response. I crawled to where he was lying. As the train passed a service light, I caught sight of his face.

Dead. The ’geists had flushed his spirit out. His ID was on the floor. William Linwood. Forty-three years old. Two kids, one with cystic fibrosis. Married. Banker. Medium.

Did his wife and children know about his secret life? Or were they amaurotic, oblivious to it?

I had to speak the threnody, or he would haunt this carriage forever. “William Linwood,” I said, “be gone into the æther. All is settled. All debts are paid. You need not dwell among the living now.”

Linwood’s spirit was drifting nearby. The æther whispered as he and his angel vanished.

The lights came back on. My throat closed.

Two more bodies lay on the floor.

I used a handrail to get back on my feet. My clammy palm could hardly grip it. A few feet away, Underguard 1 was dead, the look of surprise still on his face.

I’d killed him. I’d killed an Underguard.

His companion hadn’t been so lucky. He was on his back, his eyes staring at the ceiling, a slithering ribbon of saliva down his chin. He twitched when I came closer. Chills crept down my back and the taste of bile burned my throat. I hadn’t pushed his spirit far enough. It was still drifting in the dark parts of his mind: the secret, silent parts in which no spirit should dwell. He’d gone mad. No. I’d driven him mad.

I set my jaw. I couldn’t just leave him like this—even an Underguard didn’t deserve such a fate. I placed my cold hands on his shoulders and steeled myself for a mercy kill. He let out a groan and whispered, “Kill me.”

I had to do it. I owed it to him.

But I couldn’t. I just couldn’t kill him.

When the train arrived at Station I-5C, I waited by the door. By the time the next passengers found the bodies, they were too late to catch me. I was already above them on the street, my cap pulled down to hide my face.

2

The Liar

I slipped into the flat and hung my jacket up. The Golden Crescent complex had a full-time security guard called Vic, but he’d been doing his rounds when I swiped in. He hadn’t seen my death-white face, my shaking hands as I reached for my key card.

My father was in the living room. I could see his slippered feet propped up on the ottoman. He was watching ScionEye, the news network that covered all Scion citadels, and on the screen Scarlett Burnish was announcing that the Underground across I Cohort had just been closed.

I could never hear that voice without a shudder. Burnish was only about twenty-five, the youngest ever Grand Raconteur: the assistant of the Grand Inquisitor, the one who pledged their voice and wit to Scion. People called her Weaver’s whore, perhaps out of jealousy. She had clear skin and six-seater lips, and she favored thick red eyeliner. It matched her hair, which she wore in a chic Gibson tuck. Her high-collared dresses always made me think of the gallows.

“In foreign news, the Grand Inquisitor of the French Republic, Benoît Ménard, will be visiting Inquisitor Weaver for Novembertide festivities this year. With eight months to go, the Archon is already making preparations for what looks to be a truly invigorating visit.”

“Paige?”

I pulled off my cap. “Hi.”

“Come and sit down.”

“Just a minute.

I headed straight for the bathroom. I was sweating not so much bullets as shotgun shells.

I’d killed someone. I’d actually killed someone. Jax had always said I was capable of it—bloodless murder—but I’d never believed him. Now I was a murderer. And worse, I’d left evidence: a survivor. I didn’t have my data pad, either, and it was smothered in my fingerprints. I wouldn’t just get NiteKind—that would be too easy. Torture and the gallows, for sure.

As soon as I got to the bathroom, I vomited my guts into the toilet. By the time I’d brought up everything but my organs, I was shaking so violently I could hardly stand. I tore off my clothes and stumbled into the shower. Burning water pounded on my skin.

I’d gone too far this time. For the first time ever, I’d invaded other dreamscapes. Not just touched them.

Jaxon would be thrilled.

My eyes closed. The scene in the carriage replayed again and again. I hadn’t meant to kill them, I’d meant to give them a push— just enough to give them a migraine, maybe make their noses bleed. Cause a distraction.

But something made me panic. Fear of being found. Fear of becoming another anonymous victim of Scion.

I thought of Linwood. Voyants never protected one another, not unless they were in the same gang, but his death still weighed on me. I pulled my knees up to my chin and held my aching head in both hands. If only I’d been faster. Now two people were dead—one insane—and if I wasn’t very lucky, I’d be next.

I huddled in the corner of the shower, my knees strapped against my chest. I couldn’t hide in here forever. They always found you in the end.

I had to think. Scion had a containment procedure for these situations. Once they’d cleared the station and detained any possible witnesses, they would call a gallipot—an expert in ethereal drugs— and administer blue aster. That would temporarily restore my victim’s memories, allowing them to be seen. When they had the relevant parts recorded, they would euthanize the man and give his body to the morgue in II-6. Then they would flick through his memories, searching for the face of his killer. And then they would find me.

Arrests didn’t always happen at night. Sometimes they caught you in the day, when you stepped onto the street. A torch in your eyes, a needle in your neck, and you were gone. Nobody reported you missing.

I couldn’t think about the future now. A fresh wave of pain broke through my skull, bringing me back to the present.

I counted my options. I could go back to Dials and lie low in our den for a while, but the Vigiles might be out looking for me. Leading them to Jax wasn’t an option. Besides, with the stations closed off there was no way I could get back to Section 4. A buck cab would be hard to find, and the security systems worked ten times harder at night.

I could stay with a friend, but all my friends outside the Dials were amaurotic—girls at school I’d barely kept in touch with. They’d think I’d gone off the cot if I said I was being hunted by the secret police because I’d killed someone with my spirit. They’d almost certainly report me, too.

Wrapped in an old dressing gown, I padded barefoot to the kitchen and put a pan of milk on the stove. I always did it when I was home; I shouldn’t break routine. My father had left my favorite mug out, the big one that said GRAB LIFE BY THE COFFEE. I’d never been a fan of flavored oxygen, or Floxy®, the Scion alternative to alcohol. Coffee was just about legal. They were still researching whether or not caffeine triggered clairvoyance. But then, GRAB LIFE BY THE FLAVORED OXYGEN just wouldn’t have the same vitality.

Using my spirit had done something to my head. I could hardly keep my eyes open. As I poured the milk, I looked out of the window. My father had impeccable taste when it came to interior design. It helped that he had money enough to afford the highsecurity places on the exclusive Barbican Estate. The apartment was fresh and spacious, full of light. The hallways smelled of potpourri and linen. There were large square windows in every room. The biggest was in the living room, a vast skylight covering the westfacing wall, next to the elaborate French doors that led out to the balcony. As a child I’d often watched the sun set from that window.

Outside, the citadel whirled on. Above our complex stood the three brutalist columns of the Barbican Estate, where the whitecollar Scion workers lived. At the top of the Lauderdale Tower was the I-5 transmission screen. It was from this screen that they projected public hangings on a Sunday evening. At present it bore the Scion system’s static insignia—a red symbol resembling an anchor—and a single word in black: SCION, all on a clinical white background. Then there was that awful slogan: NO SAFER PLACE.

More like no safe place. Not for us.

I sipped my milk and looked at the symbol for a while, wishing it all the way to hell. Then I washed up my mug, poured a glass of water, and headed for my bedroom. I had to call Jaxon.

My father intercepted me in the hallway.

“Paige, wait.”

I stopped.

Irish by birth, with a scalding head of red hair, my father worked in the scientific research division of Scion. When he wasn’t doing that, he was scribbling formulas on his data pad and waxing lyrical about clinical biochemistry, one of his two degrees. We looked nothing alike.

“Hi,” I said. “Sorry I’m so late. I did some extra hours.”

“No need to apologize.” He beckoned me into the living room. “Let me get you something to eat. You look peaky.”

“I’m fine. Just tired.”

“You know, I was reading about the oxygen circuit today. Horrible case in IV-2. Underpaid staff, dirty oxygen, clients having seizures— very unpleasant.”

“The central bars are fine, honestly. The clients expect quality.” I watched him lay the table. “How’s work?”

“Good.” He looked up at me. “Paige, about your work in the bar—”

“What about it?” I said.

A daughter working in the lowest echelons of the citadel. Nothing could be more embarrassing for a man in his position. How uncomfortable he must have been when his colleagues asked about his children, expecting him to have sired a doctor or a lawyer. How they must have whispered when they realized I worked in a bar, not at the Bar. The lie was a small mercy. He could never have coped with the truth: that I was an unnatural, a criminal.

And a murderer. The thought made me sick.

“I know it isn’t my place to say this, but I think you should consider reapplying for a place at the University. That job is a dead end. Low money, no prospects. But the University—”

“No.” My voice came out harder than I’d intended. “I like my job. It was my choice.”

I still remembered the Schoolmistress giving me my final report. “I’m sorry you chose not to apply for the University, Paige,” she’d said, “but it might be for the best. You’ve had far too much time away from school. It’s not considered proper for a young lady of quality.” She’d handed me a thin, leather-bound folder bearing the school crest. “Here is an employment recommendation from your tutors. They note your aptitude for Physical Enrichment, French, and Scion History.”

I didn’t care. I’d always hated school: the uniform, the dogma. Leaving was the high point of my formative years.

“I could arrange something,” my father said. He’d so wanted an educated daughter. “You could reapply.”

“Nepotism doesn’t work on Scion,” I said. “You should know.”

“I didn’t have the choice, Paige.” A muscle flinched in his cheek. “I didn’t have that luxury.”

I didn’t want to have this conversation. I didn’t want to think of what we’d left behind.

“Still living with your boyfriend?” he said.

The boyfriend lie had always been a mistake. Ever since I’d invented him, my father had been asking to meet him. “I broke up with him,” I said. “It wasn’t right. But it’s okay. Suzette has a spare place in her apartment—you remember?”

“Suzy from school?”

“Yes.” As I spoke, a sharp pain lanced through the side of my head. I couldn’t wait for him to make dinner. I had to call Jaxon, tell him what had happened. Now.

“Actually, I’ve got a bit of a headache,” I said. “Do you mind if I turn in early?”

He came to my side and took my chin in one hand. “You always have these headaches. You’re overtired.” He brushed his thumb over my face, the shadows under my eyes. “There’s a good documentary on, if you’re up to it—I’ll get you set up on the couch.”

“Maybe tomorrow.” I gently pushed his hand away. “Do you have any painkillers?”

After a moment, he nodded. “In the bathroom. I’ll do us an Ulster fry in the morning, all right? I want to hear all your news, seillean.”

I stared at him. He hadn’t made me breakfast since I was about twelve; nor had he called me by that nickname since we’d lived in Ireland. Ten years ago. A lifetime ago.

“Paige?”

“Okay,” I said. “See you in the morning.”

I pulled away and headed for my room. My father said nothing more. He left the door ajar, as he always did when I was home. He’d never known how to act around me.

The guest room was as warm as ever. My old bedroom. I’d moved to Dials as soon as school was over, but my father had never taken a lodger—he didn’t need one. Officially, I still lived here. Easier to leave it on the records. I opened the door to the balcony, which stretched between my room and the kitchen. My skin had gone from cold to burning hot—my eyes had an odd strained feeling, like I’d stared into a light for hours. All I could see was the face of my victim—and the vacuity, the insanity, of the one I’d left alive.

That damage had been caused in seconds. My spirit wasn’t just a scout—it was a weapon. Jaxon had been waiting for this.

I found my phone and called Jaxon’s room in the den. It barely rang before he was off.

“Well, well! I thought you’d left me for the weekend. Where’s the fire, honeybee? Have you rethought the holiday? You don’t really need one, do you? I thought not. I absolutely cannot lose my walker for two days. Have a heart, darling. Excellent. I’m delighted you agree. Did you get your hands on Jane Rochford, by the way? I’ll transfer you another few thousand if you need it. Just don’t tell me that toffee-nosed bastard Didion nabbed Anne Naylor and—”

“I killed someone.”

Silence.

“Who?” Jax sounded odd.

“Underguard. They tried to detain a medium.”

“So you killed the Underguard.”

“I killed one.”

He inhaled sharply. “And the other?”

“I put him in his hadal zone.”

“Wait, you did it with your––?” When I didn’t reply, he began to laugh. I could hear him clapping his hand on his desk. “At last. At last. Paige, you little thaumaturge, you did it! You’re wasted on séances, really you are. So this man—the Underguard—he’s really a vegetable?”

“Yes.” I paused. “Am I fired?”

“Fired? By the zeitgeist, dolly, of course not! I’ve been waiting years for you to put your talents to good use. You’ve bloomed like the ambrosial flower you are, my winsome wunderkind.” I pictured him taking a celebratory puff of his cigar. “Well, well, my dreamwalker has finally entered another dreamscape. And it only took three years. Now, tell me—were you able to save the voyant?”

“No.”

“No?”

“They had three ’geists.”

“Oh, come now. No medium could control three poltergeists.”

“Well, this medium managed. He thought I was an oracle.”

His laugh was soft. “Amateurs.”

I looked out of the window at the tower. A new message had appeared: PLEASE BE AWARE OF UNEXPECTED UNDERGROUND DELAYS. “They’ve closed the Underground,” I said. “They’re trying to find me.”

“Try not to panic, Paige. It’s unbecoming.”

“Well, you’d better have a plan. The whole network’s in lockdown. I need to get out of here.”

“Oh, don’t worry about that. Even if they try and extract his memories, that Underguard’s brain is nought but a hashed brown. Are you certain you pushed him all the way to his hadal zone?”

“Yes.”

“Then it will take them at least twelve hours to extract his memories. I’m surprised the hapless chap was still alive.”

“What are you saying?”

“I’m saying you should sit tight before you run headfirst into a manhunt. You’re safer with your Scion daddy than you are here.”

“They have this address. I can’t sit here and wait to be detained.”

“You won’t be detained, O my lovely. Trust in my schmooze. Stay home, sleep away your troubles, and I’ll send Nick with the car in the ante meridiem. How does that sound?”

“I don’t like it.”

“You don’t have to like it. Just get your beauty sleep. Not that you need it,” he added. “By the way, could you do me a favor? Pop into Grub Street tomorrow and pick up those Donne elegies from Minty, will you? I can’t believe his spirit is back, it’s absolutely—”

I hung up.

Jax was a bastard. A genius, yes—but still a sycophantic, tightfisted, coldhearted bastard, like all mime-lords. But where else could I turn? I’d be vulnerable alone with a gift like mine. Jax was just the lesser of two evils.

I had to smile at that thought. It said a lot about the world when Jaxon Hall was the lesser of two evils.

I couldn’t sleep. I had to prepare. There was a palm pistol in one of the drawers, concealed under a stack of spare clothes. With it was a first edition of one of Jaxon’s pamphlets, On the Merits of Unnaturalness. It listed every major voyant type, according to his research. My copy was covered in his annotations—new ideas, voyant contact numbers. Once the pistol was loaded, I dragged a backpack out from under the bed. My emergency pack, stored here for two years, ready for the day I’d have to run. I stuffed the pamphlet into the front pocket. They couldn’t find it in my father’s home. I lay on my back, fully clothed, my hand resting on the pistol. Somewhere in the distance, in the darkness, there was thunder.

I must have fallen asleep. When I woke, something seemed wrong. The æther was too open. Voyants in the building, on the stairwell. That wasn’t old Mrs. Heron upstairs, who used a frame and always took the lift. Those were the boots of a collection unit.

They had come for me.

They had finally come.

I was on my feet at once, throwing a jacket over my shirt and pulling on my shoes and glovelettes, my hands shaking. This was what Nick had trained me for: to run like hell. I could make it to the station if I tried, but this run would test my stamina to the limit. I would have to find and hail a cab to reach Section 4. Buck cabbies would take just about anyone for a few bob, voyant fugitive or not.

I slung on my backpack, tucked the pistol into my jacket pocket, and opened the door to the balcony. The wind had blown it shut. Rain battered my clothes. I crossed the balcony, climbed onto the kitchen windowsill, grabbed the edge of the roof, and with one strong pull, I was up. By the time they reached the apartment, I’d started to run.

Bang. There went the door—no knock, no warning. A moment later, a gunshot split the night. I forced myself to keep running. I couldn’t go back. They never killed amaurotics without reason; certainly not Scion employees. The shot had most likely been from a simple tranquilizer, to shut my father up while they detained me. They would need something much, much stronger to bring me down.

The estate was quiet. I looked over the edge of the roof, surveying it. No sign of the security guard, he must be on his rounds again. It didn’t take me long to spot the paddy wagon in the car park, the van with blacked-out windows and gleaming white headlights. If anyone had taken the time to look, they would have seen the Scion symbol on its back doors.

I stepped across a gap and climbed onto a ledge. Perilously slick. My shoes and gloves had decent grip, but I’d have to watch my step. I pressed my back to the wall and edged toward an escape ladder, the rain plastering my hair to my face. I climbed up to a wrought iron balcony on the next floor, where I forced open a small window. I tore through the deserted apartment, down three flights of stairs and out through the front door of the building. I needed to get onto the street, to vanish into a dark alley.

Red lights. The NVD were parked right outside, blocking my escape. I doubled back and slammed the door, activating the security lock. With shakey hands I pulled a fire ax from its case, smashed a ground-floor window, and hauled myself into a small courtyard, cutting my arms on the glass. Then I was back in the rain, clambering up the drainpipes and windowsills, barely holding on, until I reached the roof.

My heart stopped when I saw them. The exterior of the building was infested with men in red shirts and black jackets. Several torch beams moved toward me, glaring into my eyes. My chest surged. I’d never seen that uniform in London before—were they from Scion?

“Stop where you are.”

The nearest of them stepped toward me. In his gloved hand was a gun. I backed away, feeling a vivid aura. The leader of these soldiers was an extremely powerful medium. The lights revealed a gaunt face, sharp chips of eyes, and a thin, wide mouth.

“Don’t run, Paige,” he called across the roof. “Why don’t you come out of the rain?”

I did a quick sweep of my surroundings. The next building was a derelict office block. The jump was wide, maybe twenty feet, and beyond it was a busy road. It was farther than I’d ever tried to jump—but unless I wanted to attack the medium and abandon my body, I would have to try.

“I’ll pass,” I said, and took off again.

There was a shout of alarm from the soldiers. I leapt down to a lower stretch of the roof. The medium ran after me. I could hear his feet pounding on the roof, seconds behind mine. I was trained for these pursuits. I couldn’t afford to stop, not even for a moment. I was light and slim, narrow enough to slip between rails and under fences, but so was my pursuer. When I fired a shot from the pistol over my shoulder, he ducked it without stopping. His laugh was swept up on the wind, so I couldn’t tell how close he was.

I shoved the pistol back into my jacket. There was no point in shooting; I’d only miss. I flexed my fingers, ready to catch the gutter. My muscles were hot, my lungs at bursting point. A flare in my ankle alerted me to an injury, but I had to keep going. Fight or fly. Run or die.

The medium leaped over the ledge, swift and fluid as water. Adrenaline streaked through my veins. My legs pumped, and the rain thrashed at my eyes. I leaped over flexi-pipes and ventilation ducts, building up momentum, trying to turn my sixth sense on the medium. His mind was strong, moving as fast as he was. I couldn’t pin it down, couldn’t even get a picture from it. There was nothing I could do to deter him.

As I built up speed, the adrenaline numbed the fire in my ankle. A fifteen-story drop spread out to meet me. Across the gap there was a gutter, and beyond that was a fire escape. If I could get down it, I could disappear into the throbbing veins of Section 5. I could get away. Yes, I could make it. Nick’s voice was in my head, urging me on: Knees toward your chest. Eyes on your landing spot. It was now or never. I pushed off my toes and launched myself over the precipice.

My body collided with a solid wall of brick. The impact split my lip, but I was still conscious. My fingers gripped the gutter. My feet kicked at the wall. I used what strength I had left to push myself up, biting the gutter deep into my hands. A loose coin fell from my jacket, into the dark street below.

My victory was short-lived. As I dragged myself onto the edge of the road, my palms scalding and raw, a bolt of crucifying pain tore up my spine. The shock might have made me let go, but one hand still grasped the roof. I craned my neck to look over my shoulder. A long, thin dart was buried in my lower back.

Flux.

They had flux.

The drug swept into my veins. In six seconds my whole bloodstream was compromised. I thought of two things: first that Jax was going to kill me, and second, that it didn’t matter—I was going to die anyway. I let go of the roof.

Nothing.

3

Confined

It lasted a lifetime. I couldn’t remember when it started, and I didn’t see when it would end.

I remembered movement, a throaty roar, being strapped to a hard surface. Then a needle, and the pain took over.

Reality was warped. I was close to a candle, but the flame kept bursting to the size of an inferno. I was trapped in an oven. Sweat dripped from my pores like wax. I was fire. I burned. I blistered and seared—then I was freezing, desperate for heat, feeling as if I would die. There was no middle ground. Just endless, limitless pain.

AUP Fluxion 14 was developed as a collaborative project between the medical and military divisions of Scion. It produced a crippling effect called phantasmagoria, dubbed “brain plague” by embittered voyants: a vivid series of hallucinations, caused by distortions to the human dreamscape. I fought my way through vision after vision, crying out when the pain grew too intense to bear in silence. If there is a definition for hell, this was it. It was hell.

My hair stuck to my tears as I retched, trying in vain to force the poison from my body. All I wanted was for everything to end. Whether it was sleep, unconsciousness, or death, something had to take me from this nightmare.

“There, now, treasure. We don’t want you to die just yet. We’ve already lost three today.” Cold fingers stroked my forehead. I arched my back, pulled away. If they didn’t want me to die, then why do this to me?

Dead flowers skittered past my eyes. The room twisted into a helix, around and around until I had no idea which way was up. I bit a pillow to stop the screams. I tasted blood and knew I’d bitten something else—my lip, my tongue, my cheek, who knew?

Flux didn’t just leave your system. No matter how many times you vomited or passed urine, it kept on circulating, borne by your blood, reproduced by your own cells, until you could force the antidote into your veins. I tried to plead, but I couldn’t get a note out. The pain washed over me in wave after wave after wave, until I was sure I would die.

A new voice registered.

“Enough. We need this one alive. Get the antidote, or I will see to it that you take twice the dosage she did.”

The antidote! I might yet live. I tried to see past the rippled veil of visions, but I couldn’t make out anything but the candle.

It was taking too long. Where was my antidote? It didn’t seem to matter. I wanted sleep, the longest sleep of all.

“Let me go,” I said. “Let me out.”

“She’s speaking. Bring water.”

The cold lip of a glass clashed on my teeth. I took deep, thirsty gulps. I looked up and tried to see the face of my savior.

“Please,” I said.

Two eyes looked back at me. They burst into flame.

And finally, the nightmare stopped. I fell into a deep, black sleep.

When I woke, I lay still.

I could feel enough to get a good mental picture of where I was: spread on my stomach on a rigid mattress. My throat was roasted. It was such a severe pain that I was forced to come to my senses, if only to seek water. I realized with a start that I was naked.

I pivoted onto my side, resting my weight on my elbow and hip. I could taste dry vomit in the corners of my mouth. As soon as I could focus, I reached for the æther. There were other voyants here, somewhere in this prison.

It took a while for my eyes to adjust to the gloom. I was in a single bed with cold, damp sheets. On the right was a barred window, with no glass. The floor and walls were made of stone. A bitter draft sent goose bumps racing all over me. My breath came out in tiny clouds. I pulled the sheets around my shoulders. Who the hell had taken my clothes?

A door was ajar in the corner. I could see light. I stood, testing my strength. When I was sure I wasn’t going to fall, I moved toward the light. What I found was a rudimentary bathroom. The light was coming from a single candle. There was an ancient toilet and a rusted tap, the latter of which had been placed high on the wall. The tap was perishing to the touch. When I turned the nearby valve, a deluge of freezing water engulfed me. I tried turning the valve the other way, but the water refused to heat up more than about half a degree. I decided to take turns with my limbs, dipping one after the other under the crude excuse for a shower. There were no towels, so I used the sheets on the bed to dry off, keeping one wrapped around me. When I tried the main door, I found it locked.

My skin prickled. I had no idea where I was, or why I was here, or what these people would do to me. Nobody knew what happened to detainees; none of them had ever come back.

I sat on the bed and took a few deep breaths. I was still weak from hours of phantasmagoria, and I didn’t need a mirror to know I looked even more like a corpse than usual.

My shivers weren’t just from the cold. I was naked and alone in a dark room, with bars at the window and no sign of an escape route. They must have taken me to the Tower. Taken my backpack, too, and the pamphlet. I huddled against the bedpost and tried my best to conserve my body heat, my heart thumping. A thick knot filled my aching throat.

Would they hurt my father? He was valuable, yes—a commodity—but would he be forgiven for harboring a voyant? That was misprision. But he was important. They had to spare him.

For a while I lost track of time. I fell into a fitful doze. Finally the door crashed open, and I snapped awake.

“Get up.”

A paraffin lamp swung into the room. Holding it was a woman. She had polished nut-brown skin and an elegant bone structure, and she was taller than me by several inches. Her loosely curled hair was long and black, as was her high-waisted dress, the sleeves of which fell to the tips of her gloved fingers. It was impossible to guess her age: she could have been twenty-five or forty. I clutched the sheet around my body, watching her.

I noticed three odd things about the woman. First, her eyes were yellow. Not the kind of amber you might call yellow in certain lights. These were real yellow, almost chartreuse, and they glowed.

The second thing was her aura. She was voyant, but I’d never encountered this type before. I couldn’t pinpoint why exactly it was strange, but it didn’t sit well with my senses.

And the third—the one that chilled me—was her dreamscape. Exactly like the one I’d felt in I-4, the one we hadn’t been able to identify. The stranger. My instinct was to attack her, but I already knew I wouldn’t be able to breach that kind of dreamscape, certainly not in my current state.

“Is this the Tower?” My voice was hoarse.

The woman ignored my question. She moved her lamp close to my face, scrutinizing my eyes. I started to wonder if this was still brain plague.

“Take these,” she said.

I looked at the two pills in her hand.

“Take them.”

“No,” I said.

She hit me. I tasted blood. I wanted to hit back, to fight, but I was so weak I could barely lift my hand. With difficulty, given my freshly burst lip, I took the pills. “Cover yourself,” my captor said. “If you disobey me again, I will ensure you never leave this room. Not with flesh on your bones.”

She threw a bundle of clothes at me.

“Pick them up.”

I didn’t want to be hit again. I’d fall this time. With my jaw set tight, I picked them up.

“Put them on.”

I looked down at the clothes, dripping blood from my lip. A spot grew on the white tunic in my hands. It had long sleeves and a square neckline. With it was a black sash, matched with trousers, socks, and boots, a set of plain underwear and a black gilet stitched with a small white anchor. Scion’s symbol. I dressed in rigid strokes, forcing my cold limbs to move. When I was finished, she turned to the door. “Follow me. Do not speak to anyone.”

It was deathly cold outside the room, and the threadbare carpet did little to improve the temperature. It must have been red once, but now it was faded and stained with vomit. My guide led me through a labyrinth of stone corridors, past small barred windows and burning torches. They seemed too bright, too raw, after the cool blue streetlights of London.

Could this be a castle? I didn’t know anywhere within a thousand miles of London that had a castle—we hadn’t had a monarch since Victoria. Maybe it was one of the old Category D prisons. Unless it was the Tower.

I risked a glance outside. It was night, but I could see a courtyard by the light of several lanterns. I wondered how long I’d been under the influence of flux. Had this woman watched me as I struggled? Did she take orders from the NVD, or did they take orders from her? Maybe she worked for the Archon, but they wouldn’t employ a voyant. And whatever else she might be, she was most definitely voyant.

The woman stopped outside a door. A boy was shoved out from inside. He was a skinny, rat-faced creature, with a mop of sandy hair, and all the symptoms of flux poisoning: glazed eyes, bone-white face, blue lips. The woman looked him up and down.

“Name?”

“Carl,” he rasped.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Carl.” You could tell he was in agony.

“Well, congratulations on surviving Fluxion 14, Carl.” She sounded anything but congratulatory. “That may have been the last sleep you have for a while.”

Carl and I exchanged a glance. I knew I must look as awful as he did.

As we traipsed through the corridors, we collected several more captive voyants. Their auras were strong and distinctive; I could hazard a guess at what they all were. A seer. A chiromancer—palmist—with a pixie cut dyed electric blue. A tasseographer. An oracle with a shaved head. A slim and thin-lipped brunette, probably a whisperer, who seemed to have a broken arm. None of them looked much older than twenty, or much younger than fifteen. All of them were pale and sick from flux. In the end there were ten of us. The woman turned to face her little flock of freaks.

“I am Pleione Sualocin,” she said. “I will be your guide for your first day in Sheol I. Tonight you will attend the welcome oration. There are a number of simple rules you are expected to observe. You will not look any Rephaite in the eye. You will keep your gazes on the floor, where they belong, unless you are invited to look at something else.”

The palmist raised a hand, she kept her eyes on her feet. “Rephaite?”

“You will find out soon enough.” Pleione paused. “An additional rule: you will not speak unless a Rephaite addresses you. Is there any confusion on these matters?”

“Yeah, there is.” It was the tasser that spoke. He was not looking at the floor. “Where are we?”

“You are about to find out.”

“What the hell gives you the right to nib us? I weren’t even busking. I ain’t no lawbreaker. Prove I’ve got an aura! I’ll go straight back to the city and you ain’t going to—”

He stopped. Two dark beads of blood seeped from his eyes. He made a soft sound before he collapsed.

The palmist screamed.

Pleione assessed the tasser’s form. When she looked up at us, her eyes were gas-flame blue. I swerved my gaze away from them.

“Any other questions?”

The palmist clapped a hand over her mouth.

We were herded into a small room. Wet walls and floor, dark as a crypt. Pleione locked us in and left.

For a minute, nobody dared speak. The palmist heaved out sobs, close to hysteria. Most of the others were still too weak to talk. I sat down in a corner, out of the way. Beneath my sleeves, my skin was stippled with gooseflesh.

“Is this still the Tower?” said an augur. “It looks like the Tower.”

“Shut up,” someone said. “Just shut up.”

Someone started praying to the zeitgeist, of all things. Like that would help. I rested my chin on my knees. I didn’t want to know what they would do to us. I didn’t know how strong I’d be if they put me on the waterboard. I’d heard my father talk about it, how they only let you breathe for a few seconds at a time. He said it wasn’t torture. It was therapy.

A seer sat down beside me. He was bald and broad-shouldered. I couldn’t see much of him in the gloom, but I could see his large, intensely dark eyes. He extended a hand.

“Julian.”

He didn’t seem afraid. Just quiet. “Paige,” I said. Best not to use full names. I cleared my dry throat. “What’s your cohort?”

“IV-6.”

“I-4.”

“That’s the White Binder’s territory.” I nodded. “Which part?”

“Soho,” I said. If I said I was in Dials, he’d know I must be one of Jaxon’s nearest and dearest.

“I envy you. I’d love to have lived central.”

“Why?”

“Syndicate’s strong there. My section doesn’t see much action.” He kept his voice low. “Did you give them a reason to arrest you?”

“Killed an Underguard.” My throat ached. “You?”

“Minor disagreement with a Vigile. Long story short, the Vigile is no longer with us.”

“But you’re a seer.” Most voyants regarded seers—a class of soothsayer—with disdain. Like all soothsayers, they communed with spirits through objects; in a seer’s case, anything reflective. Jax hated soothsayers with a passion (“shitsayers, dolly, call them shitsayers”). And augurs, come to think of it.

Julian seemed to read these thoughts. “You don’t think seers capable of murder.”

“Not with spirits. You couldn’t control a big enough spool.”

“You do know your voyants.” He rubbed his arms. “You’re right. I shot him. Didn’t stop them arresting me.”

I didn’t reply. Icy water dripped from the ceiling, onto my hair, and ran down my nose. Most of the other prisoners were silent. One boy was rocking back and forth on his heels.

“You have a strange aura.” Julian looked at me. “I can’t work out what you are. I’d say oracle, but—”

“But?”

“I haven’t heard of a woman being an oracle in a long time. And I don’t think you’re a sibyl.”

“I’m an acultomancer.”

“What’d you do, stab someone with a needle?”

“Something like that.”

There was a crash from outside, and an awful scream. Everyone stopped talking.

“That’s a berserker.” The voice was male, afraid. “They’re not going to put a berserker in here, are they?”

“There’s no such thing as a berserker,” I said.

“Have you not read On the Merits?”

“Yes. It’s a hypothetical type.”

He didn’t look relieved. The thought of the pamphlet made me colder than ever. It could be anywhere, in anyone’s hands—a first edition of the most seditious pamphlet in the citadel, covered in fresh notes and contact details. I could never have got such a thing without knowing the writer.

“They’re going to torture us again.” The whisperer was cradling her broken arm. “They want something. They wouldn’t have just let us out.”

“Out of where?” I said.

“The Tower, idiot. Where we’ve all been for the last two years.”

“Two?” There was a half-hysterical laugh from the corner. “Try nine. Nine years.” Another laugh, a giggle.

Nine years. Why nine? From what we knew, detainees were given two choices: join the NVD or be executed. There was no need to store people. “Why nine?” I said.

There was no answer from the corner. After a minute, Julian spoke up.

“Anyone else wondering why we’re not dead?”

“They killed everyone else.” A new voice. “I was there for months. The other voyants in my wing all got the noose.” Pause. “We’ve been picked for something else.”

“SciSORS,” somebody whispered. “We’re gonna be lab rats, aren’t we? The doctors want to cut us up.”

“This isn’t SciSORS,” I said.

There was a long silence, broken only by the bitter tears of the palmist. She couldn’t seem to stop. Finally, Carl addressed the whisperer. “You said they must want something, hisser. What could they want?”

“Anything. Our sight.”

“They can’t take our sight,” I said.

“Please. You’re not even sighted. They won’t want disabled voyants.”

I resisted the urge to break her other arm.

“What did she do to the taser?” The palmist was shaking. “His eyes—she didn’t even move!”

“Well, I thought we’d be killed for sure,” Carl said, as if he couldn’t imagine why the rest of us were so worried. His voice was less hoarse. “I’d take anything over the noose, wouldn’t you?”

“We might still get the noose,” I said.

He fell silent.

Another boy, so pale it looked as if the flux had burned the blood out of his veins, was beginning to hyperventilate. Freckles dusted his nose. I hadn’t noticed him before; he had no trace of an aura. “What is this place?” He could hardly get the words out. “Who—who are you people?”

Julian glanced at him. “You’re amaurotic,” he said. “Why have they taken you?”

“Amaurotic?”

“Probably a mistake.” The oracle seemed bored. “They’ll kill him all the same. Tough luck, kid.”

The boy looked as though he might faint. He leaped to his feet and yanked at the bars.

“I’m not meant to be here. I want to go home! I’m not unnatural, I’m not!” He was almost in tears. “I’m sorry, I’m sorry about the stone!”

I clapped a hand over his mouth. “Stop it.” A few of the others swore at him. “You want her to reef you, too?”

He was trembling. I guessed he was about fifteen, but a weak fifteen. I was forcefully reminded of a different time—a time when I was frightened and alone.

“What’s your name?” I tried to sound gentle.

“Seb. S-Seb Pearce.” He crossed his arms, trying to make himself smaller. “Are you—are you all—unnaturals?”

“Yeah, and we’ll do unnatural things to your internal organs if you don’t shut your rotten trap,” a voice sneered. Seb cringed.

“No, we won’t,” I said. “I’m Paige. This is Julian.”

Julian just nodded. It looked like it was my job to make small talk with the amaurotic. “Where are you from, Seb?” I said.

“III Cohort.”

“The ring,” Julian said. “Nice.”

Seb looked away. His lips shook with cold. No doubt he thought we’d chop him up and bathe in his blood in an occult frenzy.

The ring was where I’d gone to secondary school, a street name for III Cohort. “Tell us what happened,” I said.

He glanced at the others. I couldn’t find it in myself to blame him for his fear. He’d been told from the second he could talk that clairvoyants were the source of all the world’s evils, and here he was in a prison with them. “One of the sixth-formers planted contraband in my satchel,” he said. Probably a show stone, the most common numen on the black market. “The Schoolmaster saw me trying to give it back to them in class. He thought I’d got it from one of those beggar types. They called the school Vigiles to check me.”

Definitely a Scion kid. If his school had its own Gillies, he must be from an astronomically rich family.

“It took hours to convince them I’d been framed. I took a shortcut home.” Seb swallowed. “There were two men in red on the corner. I tried to walk past them, but they heard me. They wore masks. I don’t know why, but I ran. I was scared. Then I heard a gunshot, and—and then I think I must have fainted. And then I was sick.”

I wondered about the effects of flux on amaurotics. It made sense that the physical symptoms would appear—vomiting, thirst, inexplicable terror—but not phantasmagoria. “That’s awful,” I said. “I’m sure this is all a terrible mistake.” And I was sure. There was no way a well-bred amaurotic kid like Seb should be here.

Seb looked encouraged. “Then they’ll let me go home?”

“No,” Julian said.

My ears pricked. Footsteps. Pleione was back. She pulled open the door, grabbed the nearest prisoner, and hauled him to his feet with one hand. “Follow me. Remember the rules.”

We left the building through a set of double doors, the palmist guided by the whisperer. The frigid air hit every inch of exposed skin. I started when we came to the gallows—maybe this was the Tower—but Pleione walked past it. I had no idea what she’d done to the tasser, or what the scream had been, but I wasn’t about to ask. Head down, eyes open. That would be my rule here, too.

She led us through deserted streets, illuminated by gaslight and wet after a night of heavy rain. Julian fell into step beside me. As we walked, the buildings grew larger—but they weren’t skyscrapers. They were nowhere near that scale. No metal framework, no electric light. These buildings were old and unfamiliar, built when aesthetic tastes were different. Stone walls, wooden doors, leaded windows glazed with deep red and amethyst. When we rounded the last corner, we were greeted by a sight I would never forget.

The street that stretched in front of us was oddly wide. There wasn’t a car in sight: just a long line of ramshackle dwellings, winding drunkenly from one end to the other. Plywood walls propped up slats of corrugated metal. On either side of this little town were larger buildings. They had heavy wooden doors, high windows, and crenellation, like the castles of Victoria’s days. They reminded me so much of the Tower that I had to look away.

Several feet from the nearest hut, a group of svelte figures stood on an open-air stage. Candles had been placed all around them, illuminating their masked faces. A violin sang below the boards. Voyant music, the sort only a whisperer could perform. Looking up at them was a large audience. Every member of that audience wore a red tunic and a black gilet.

As if they’d been awaiting our arrival, the figures began to dance. They were all clairvoyant; in fact, everyone here was clairvoyant— the dancers, the spectators, everyone. Never in my life had I seen so many voyants in one place, standing peacefully together. There must have been a hundred observers clustered around the stage.

This was no secret meeting in an underground tunnel. This wasn’t Hector’s brutal syndicate. This was different. When Seb reached for my hand, I didn’t shake him off.

The show went on for a few minutes. Not all of the spectators were paying attention. Some were talking among themselves, others jeering at the stage. I was sure I heard someone say “cowards.” After the dance, a girl in a black leotard stepped out onto a higher platform. Her dark hair was slicked back into a bun, and her mask was gold and winged. She stood there for a moment, still as glass—then she jumped from the platform and seized two long red drapes that had been dropped from the rigging. Weaving her legs and arms around them, she climbed up twenty feet before unraveling into a pose. She earned a smattering of applause from the audience.