So, that’s what I mean by saying that the world is upside-down. The world is not well-arranged. It is not well-arranged, and therefore there is no way that we can be happy with it—no way, even as writers.

–Chinua Achebe, 1988

I was raised Catholic, and I took it seriously. Though eventually I lapsed from the church, certain habits of mind I developed when I was quite young are still with me. One of them is looking at the world through the lens of right and wrong. I am a moralist.

The problem with viewing the world this way is that the world will make you crazy, or profoundly depressed, or murderously angry, sometimes all three at once. None of these emotions are useful. They won’t help you make the world any better; they are as likely to poison your actions as motivate them.

Every day gives new evidence of humanity’s inability to handle the products of its ingenuity. The globe itself is being poisoned by the byproducts of civilization. Lethal politics, religious intolerance, ethnic strife, greed, ideology, shortsightedness, vanity, imbecility, a lack of regard for and active hostility toward others—the news every day offers examples of all of these things, at the macroscopic and microscopic levels, done by nation states, whole populaces, by the guy next door or the person at the next spot at the bar. Every day I participate in them myself.

So how does a writer deal with this?

Escape is good. We write stories that take us away to some simpler and more gratifying place. That’s why I started reading science fiction when I was a boy.

Rage is another way. From Ecclesiastes to Jonathan Swift to Mark Twain, literature is full of examples of writers who blast the human race to smithereens.

Laughter helps. It’s not surprising, under these circumstances, that many writers turn to mockery.

Buy the Book

War with the Newts

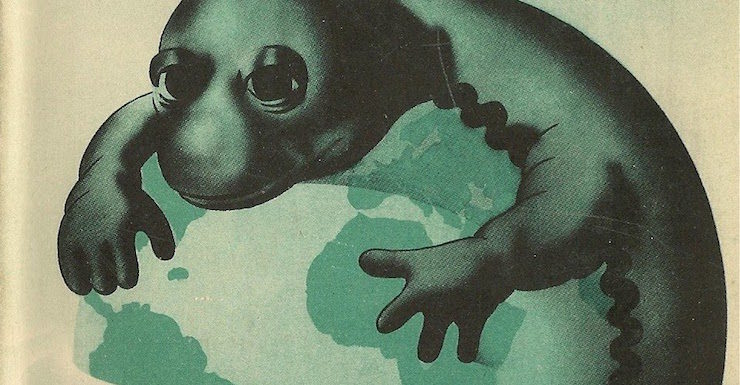

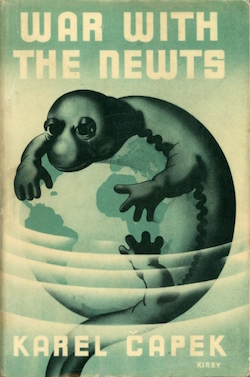

I liked this kind of story from the time I discovered Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle when I was thirteen. But I did not really get how powerful the satirical mode could be until I read Karel Čapek. You may not know his work. To say that Čapek (1890-1938) is one of the greatest writers in Czech literature is to give him insufficient credit. He’s probably most famous for giving us the word “robot,” which first appeared in his 1920 science fiction play “Rossum’s Universal Robots.” Much of Čapek’s work is comic, much of it surreal, and a significant portion of it SF, including his 1936 novel War With the Newts.

War With the Newts is one of the funniest, most corrosive books ever written. There is no aspect of human behavior that it does not put in its crosshairs. You could say this does not lend itself to a unified story line, and you would be right. After a somewhat conventional opening, Čapek tells his story in a series of anecdotes, dramatizations, newspaper reports, scientific papers, and footnotes. The conceit is that a character living in the time leading up to the war has been collecting clippings, and what we have in Čapek’s text is a dump from his archive.

This enables Čapek to jump from one bit to another without worrying too much about transitions. “Monty Python’s Flying Circus” avoided the problem that the premise of most comedy sketches wears thin after about three minutes with “…and now for something completely different.” That’s essentially what Čapek does here.

The story starts with the discovery by an eccentric sea captain of a species of three-foot-tall intelligent salamanders living in a lagoon on an island in the Indian Ocean. Captain van Toch liberates them from the island and spreads them across the Pacific, using them to hunt pearls. Soon Newts are being shipped all around the world and bred for slave labor. A big, profitable market in Newts develops.

But humans become addicted to Newt labor, seeing as it’s so cheap. Millions of poor humans are displaced and starve to death. Newts do the most terrible work, dying by the thousands, but making some people an awful lot of money. They multiply rapidly. It’s not very long before nations realize that they can use Newts in military operations. Soon there are Newt armies that far outnumber human armies. You can guess what happens next.

It’s amazing how many ways Čapek uses his Newts to demonstrate that humans are silly, cruel, stupid, greedy, clueless, obsessive, and ultimately insane. Some examples:

- We visit a Newt displayed in a sideshow. Another in the London zoo, who reads a tabloid newspaper given him by the janitor. “Sporting Newts” are harnessed to tow shells in races and regattas. There are Hollywood newts. “The Salamander Dance” becomes a popular dance craze.

- We read the minutes of the board of directors of the Salamander Syndicate, where businessmen apply the brutal logic of capitalism to their trade in Newts. “The catch and transportation of Newts would be entrusted to trained personnel only and operated under proper supervision. One could not, of course, guarantee the manner in which contractors buying the Newts would treat them.” Only 25 to 30 percent of Newts survive transportation in the holds of cargo ships. Explicit comparison is made to the African slave trade.

- Scientists, to prove that normally poisonous Newt flesh may be made edible, boil and eat their laboratory assistant Hans, “an educated and clever animal with a special talent for scientific work … we were sorry to lose Hans but he had lost his sight in the course of my trepanation experiments.”

- A footnote tells us that in the U.S., Newts accused of raping women are regularly lynched. American Blacks who organize a movement against Newt lynching are accused of being political.

- After the Chief Salamander calls for “lebensraum” for the expanding Newt population, Newts in bowler hats and three piece suits come to a peace conference.

Despite the outrages so calmly delineated, this is a very funny book. Reading War With The Newts, I recognize that nothing has changed in human behavior since the 1930s. But Čapek wants us to do better. The book ends with a chapter in which the author argues with himself, trying to come up with a happy ending—one where the human race is not exterminated—but finding no logical way out.

At the publication of War With the Newts Čapek was one of the most famous writers in Europe, a personal friend of the Czech President Tomas Masaryk. He was an outspoken advocate of democracy, an opponent of both communism and fascism. He vocally opposed the appeasement of the Nazis leading up to WWII, earning Hitler’s enmity. When the Germans violated the Munich Pact and marched into Prague in March 1939, one of the first places they went was to Čapek’s home to arrest him.

Unfortunately for them, Čapek had died of pneumonia a couple of months earlier, on Christmas Day 1938. He most certainly would have enjoyed the spectacle of fascists seeking to arrest a man whom they had not the wit to discover was already dead. It would have made an appropriate clipping to include in War With the Newts.

I agree with Vonnegut, who said that Čapek, “speaks to the present in a voice brilliant, clear, honorable, blackly funny, and prophetic.” War With the Newts taught me to laugh when my heart was bent with rage, and for that I am grateful.

John Kessel‘s novel Pride and Prometheus was published by Simon and Schuster in February. His other works include The Moon and the Other, Good News from Outer Space, Corrupting Dr. Nice, and The Baum Plan for Financial Independence and Other Stories. He teaches in the MFA program at North Carolina State University.

John Kessel‘s novel Pride and Prometheus was published by Simon and Schuster in February. His other works include The Moon and the Other, Good News from Outer Space, Corrupting Dr. Nice, and The Baum Plan for Financial Independence and Other Stories. He teaches in the MFA program at North Carolina State University.