Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

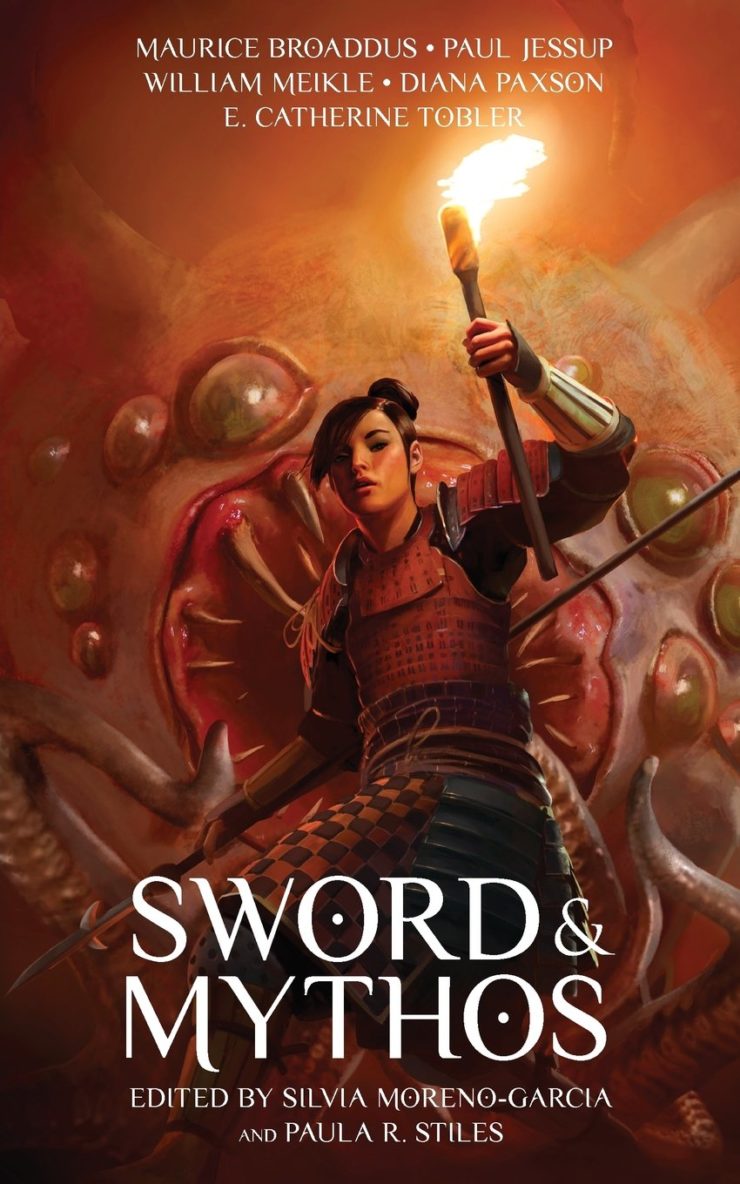

This week, we’re reading Maurice Broaddus’ “The Iron Hut,” first published in Silvia Moreno-Garcia and Paula R. Stiles’ 2014 Sword and Mythos anthology. Spoilers ahead.

“Like living scrolls, the men had words—old words not meant to be pronounced by human tongues, carved into their flesh.”

Part I: Miskatonic professor Leopold Watson leads an archaeological expedition to Tanzania, seeking the legendary city of Kilwa Kivinje. The dig uncovers a crystalline shard engraved with what may be the earliest inscription ever discovered, possibly in archaic proto-Bantu. Or even in a language not quite human, like those Watson’s read of in the Miskatonic archives.

The Pickman Foundation has funded the expedition and sent a representative in the slothlike yet overbearing Stanley McKreager. While the shard makes Watson nauseous, McKreager peers with clueless fascination. He suggests they publicize the shard as an artifact of Atlantis. Of course Africans couldn’t have fashioned the protolinguistic shard—the Foundation wouldn’t like that! Stomach churning at the fabrication, Watson proposes a compromise attribution to Portuguese artisans, or Portuguese-trained Africans.

He goes to his tent, thinking of Elder Things and regretting his time among the Miskatonic tomes. Falling into troubled sleep, he dreams of ancient warriors.

Part II: What price friendship, Nok warrior Dinga wonders as he struggles up the mountain towering over Kilwa Kivinje. An icy storm rages, daunting even to an experienced hillman. He never trusted the laibon (ritual leader) who sent him on this fool’s errand, but a friend’s life hangs in the balance.

It started a couple days earlier, when Berber thieves attacked Dinga. He welcomes the chance to honor his god Onyame by slaying them. An old friend, Masai warrior Naiteru, appears in the nick of time, not that Dinga needs help. The two banter in comradely fashion as they slaughter the thieves. But Naiteru’s minor wound bleeds unaccountably. They set off for nearby Kilwa to heal up.

Part III: Dinga finds a subterranean passage that twists deep into the mountain’s rocky bowels. Faint amber light reveals cryptic carvings on strangely angled walls. Some carvings resemble his own tattoos, but that’s a mystery for another day. Right now he’s concerned with the human bones littering the passage, and the mummified corpse of a crystal-encased warrior. Hunter’s instinct warns him he’s not alone; from deeper in the mountain come strange cries and scraping footfalls. He raises his sword and waits.

Flashback to Dinga and Naiteru’s arrival at Kilwa. During their trek, Naiteru’s condition has worsened. Dinga remembers how Naiteru’s father took in Dinga as a boy, making them brothers. To his surprise, Kilwa Kivinje turns out to be no village of mud-and-wattle huts but a stone-walled city of magnificent houses and iron smelting furnaces. Kaina, laibon of the Chagga people, welcomes the wounded warriors. He provides food and wine and the healing attentions of maiden Esiankiki, but Dinga mistrusts him as he does all magicians. Kaina tells them Naiteru’s father has died of a plague caused by “necromantic magic and strange creatures called from the Night.” Dinga’s mistrust grows. Too late he suspects his wine’s drugged.

Back inside the mountain: Dinga’s attacked by star-headed, bat-winged, tentacled monsters. He slays them and warms himself on their green-oozing bodies, tauntaun-like, before moving on.

Flashback to Dinga waking bound. Naiteru lies nearby, failing. Kaina accuses Dinga of being the plague-bringer—he’s foreseen that Dinga will destroy the city. He puts Dinga to the Trial by Ordeal, forcing him to drink a poisoned concoction. Dinga survives, proving he’s not a member of the Brotherhood of the Higher Ones who live in an iron hut atop the mountain. They are the ones sickening the land. To save Naiteru and the city, Dinga must confront them.

And so he’s come at last to that iron hut, through a hall of paintings that show people worshipping creatures from the sea. In the hut kneel horribly mutilated men and their witch-mother, an ancient white-skinned crone. Gelatinous eggs cling to the wall behind her.

Buy the Book

Flyaway

Dinga slays the men. But the witch-mother laughs as the air splits between them, emitting a sickly yellow-green glow. Dinga’s vigor, she says, will call forth the Dweller Outside! Knowing no counter-ritual, Dinga runs her through. A bestial howl sounds from beyond, and an ebon tentacle lashes from the split to entomb the dying witch-mother in crystal.

The altar tears from the wall, revealing a passage. Dinga escapes as an explosion erupts behind…

He returns to Kilwa Kivinje to find the city utterly destroyed. The stench of burned flesh reigns. Crystal shards lie scattered. Naiteru alone “survives,” no longer Dinga’s friend but Naiteru-Kop, touched by the Old Ones and destined one day to usher them into this plane. He easily counters Dinga’s attack, saying they’ll meet again.

Part VI: Professor Watson wakes, sweating with dread. He’s certain their discoveries have awakened something. He flees the camp but sees McKreager staggering after him, clutching the shard. The man’s skull splinters, bones shattering in five directions. He emits words of a weird musical quality.

Watson begins to laugh. A terrible, cold laughter.

What’s Cyclopean: There are “lurking horrors” in the “wavering ebon murk.”

The Degenerate Dutch: McCreager is much more comfortable with the idea of Atlantean ruins than with African artisans producing exquisite work before Europeans—or at least he’s pretty sure his bosses will prefer the Atlantean hypothesis.

Mythos Making: The framing story involves an ill-fated Miskatonic University expedition funded by the Nathaniel Derby Pickman Foundation. Watson mentions records of elder things, and the things themselves appear as relatively-easily-skewered foes in Dinga’s adventure.

Libronomicon: Leopold reads a “damnable book” at Miskatonic, but at least it’s written on non-living material—unlike most of the writing that Dinga encounters. Then there’s the nauseating writing on the crystal shard, written in “a tongue long dead and not quite human.”

Madness Takes Its Toll: Dinga and his Chagga hosts accuse each other of falling prey to madness, by which they both seem to mean random acts of violence and/or sorcery.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

“The Iron Hut” comes originally from Sword and Mythos, a Moreno-Garcia anthology that’s unfortunately extremely out of print. Which is a pity, because cosmic horror and sword-and-sorcery started as sibling subgenres, but are rarely seen in company these days—and even less in a setting both fond of both and deeply aware of their original flaws. Broaddus provides an exception in the old tradition: Dinga wanders as a semi-lone warrior through a series of “sword and soul” stories informed by African history and culture. Broaddus credits Canadian fantasist Charles Saunders with founding this tradition, and inspiring Dinga’s stories, in his Imaro series.

Both sword fantasy and mythos are prone to poorly-researched exoticization—or plain old villainization—of African cultures, so finding something that keeps the drama-filled adventure while shoring up the foundation is delightful fair play. The Chagga, for example, feel like they’re following real cultural patterns—they may only be on page long enough for a dramatic life-or-death test and some exposition, but one gets the impression that most of their customs don’t involve tying up heroes.

We’ve covered samples of older sword/mythos overlap via C.L. Moore and Robert Howard. Epic heroes must encounter something that can stand against strength, cleverness, and enchanted swords—and entities beyond human comprehension are often inconveniently hard to hit. Plus said entities tend to be worshipped by cults following obscene practices in ornate-yet-non-Euclidean temples, which makes for great pulpy scene-setting. These temples—like the one Dinga finds—may even be carved with unreasonably informative bas reliefs to summarize the incomprehensible. (I have a serious soft spot for unreasonably informative bas reliefs, and may have startled my kids with inexplicable parental delight when one showed up in a cavern beneath Dinotopia.)

An old-fashioned cult needs not only excellent décor, but rituals that would be disturbing even if they didn’t culminate in summoning ancient horrors. Broaddus’s face-sewn summoners remind me of Llewellyn’s (much less safe for work) body-horror-filled rituals. Like many who try to commune with elder gods, they also benefit from non-human attendants. I have to admit that I wanted more elder things than I got—from Dinga’s perspective, they’re basically monsters of the week. Given that they represent one of Lovecraft’s first complex non-human cultures, and given that Dinga is as much trickster as fighter, I’d have loved to watch him talk his way around them, dealing with them as people rather than mere radially symmetrical goons.

The confrontation with the elder things reminded me of another barbarian dealing with the unnamable: Campbell in “Challenge From Beyond,” dragged from Lovecraftian fear to Howard-ish joie-de-vivre and the conquest of an alien world. You can react existentially to aliens and elder gods, or you can take a more practical approach. Dinga is definitely on the practical side—which serves him well, until it doesn’t. Running the danger through with a sword, he learns, only goes so far when the danger isn’t entirely physical. And his friend pays the price.

And not only his friend—I haven’t until now mentioned the framing story. I wasn’t entirely sure what to make of Leopold Watson, who seems to have gotten funding for an expedition he didn’t want (but maybe needed for tenure?). At the same time, I was drawn to the politics of archaeological interpretation, and the deep-time question of what survives from an ancient, adventurous life. Leopold’s funding partner would rather Atlantis than real African art and culture, and is perfectly happy to direct the claims that come out of their dig. Except that what actually comes out of the dig is inhuman horror that kills/transforms said partner and costs Watson his life, mind, and/or sanity. He’s named for an interloper and a perennial witness, and suffers the worst consequences of both. Is that due to the expedition’s failure to respect the real history? Or is it just the inevitable risk of Miskatonic’s unique approach to archaeology?

Anne’s Commentary

I wonder if Broaddus christened Professor Leopold Watson after Leopold II of Belgium, founder and sole owner of the ironically named Congo Free State. Leopold II may not be able to claim sole ownership of the title Vicious Colonial Ruler, but he’s a top contender for Most Vicious, given the millions of Africans mutilated or killed for his personal enrichment. Professor Leopold is no King Leopold, but neither has he the guts to stand up to the racial prejudices of his expedition sponsor and their watchdog McKreager.

That sponsor is the Nathaniel Derby Pickman Foundation, which also sponsored the 1930 Dyer-Pabodie expedition to Antarctica. Broaddus doesn’t tell us when Watson’s Tanzanian expedition takes place, so I’m going to imagine it too set forth in the 1930s, a decade when the Foundation appears to have been particularly flush and ambitious. I don’t know about the NDPF. Its ventures suffer from high mortality. Is it bad luck its explorers keep stumbling across Old Ones and Elder Things, or does the NDPF hope to, intend to, uncover Old Ones and Elder Things? You can’t put that kind of shenanigans past an organization named after a Pickman and closely associated with Miskatonic. Its whole board are probably Brethren of the Higher Ones!

The Associated Press is also in on it, because it’s the chief news purveyor for both expeditions. Go ahead and call me paranoid, but the fictional facts speak for themselves.

Conspiracy theorizing aside, for the moment, Lovecraft tells us in “At the Mountains of Madness” that Elder Things first made Earthfall on the part of the Paleozoic supercontinent that would become Antarctica; though that region remained sacred to them, they migrated to all parts of the planet. An early stop was doubtless Africa—its present day southeastern coast impinged on the present day northwestern coast of Antarctica. Tanzania would have been an easy commute.

More Lovecraft canon: The pervasive wall carvings studied by Dyer and Danforth indicate the Elder Things kickstarted Earth’s life. After they’d cultured enough shoggoths to do their heavy work, they allowed leftover protocells to differentiate at evolutionary whim into ancestors of today’s flora and fauna. That is, unless that undirected evolution spawned creatures inconvenient to them. These they eradicated.

One species that escaped eradication was a “shambling primitive mammal, used sometimes for food and sometimes as an amusing buffoon…whose vaguely simian and human foreshadowings were unmistakable.” Protohomo buffoonicus might have originated near African Elder Thing settlements and been exported elsewhere, for the entertainment and snacking needs of other ETs. Forward-thinking Elder Things might have cultivated the intelligence of early hominids. First, potentially intelligent hominids were nowhere near as threatening as potentially intelligent shoggoths. Second, given the vagaries of cosmic cycles, Elder Things would likely need surviving native species smart enough to one day Reopen the Doors and Bring Them Back.

Smart enough, that is, to learn the Sorcery required to trick brawny Swords into serving as flesh-and-spirit batteries for Rift Repair. Tanzania’s a fine place to set a sword and sorcery/Mythos hybrid. At first I was confused by where exactly in Tanzania Watson hopes to find his legendary Kilwa Kivinje. Kilwa Kivinje is a real town, but it’s a 19th-century Arab trading post on the east coast of the country, now (as Lonely Planet puts it) “a crumbling, moss-covered and atmospheric relic of the past.” Just not so distant a past as to merit “legendary” status. Watson notes that his Kilwa Kivinje is not far from the Olduvai Gorge, cradle of humanity. By not far I was thinking in Rhode-Island terms, say, a coupla blocks ovah. But Watson’s camped beneath ice-capped “peaks of mystery” that must be Mt. Kilimanjaro, with its three volcanic cones—two in the legend of Mawenzi and Kibo that Watson relates to McKreager; Shira’s the third cone. Kilimanjaro’s also known by the Masai name Oldoinyo Oibor or “white mountain.” Oldoinyo Oibor is what towers over Dinga’s Kilwa Kivinje. I think I’m figuring out my geography now. The Olduvai Gorge is over 200 kilometers from Kilimanjaro. I guess that’s “not far” for Watson. He’s obviously not from Rhode Island.

Anyhow. Though I’m not big on the sword and sorcery subgenre, I enjoyed Dinga’s blade-badassery and felt for his wanderer’s fate. At the same time, I kind of enjoyed how the sorcerers win in the end. Kaina and the witch-mother bite the shardy dust, but a new magician-servant to the Old Ones emerges in Naiteru, and even Dinga can’t run him through. I suspect, being suspicious, that Naiteru may have set his friend up to take out the sorcerers in his way to becoming top magical dog. Why did he show up just in time to lead Dinga to Kilwa Kivinje, arriving there just in time to present Kaina with a solution (ha!) to his Brethren problem. Or was Kaina hoping that when Dinga killed the witch-mother, Kaina could take over as Higher-One/Old-One intermediary? Ha again! Secret sorcerer Naiteru knew that if Old Ones had a choice of touching Kaina or him, ha thrice, no contest.

I’m not paranoid or anything. It’s perfectly reasonable to question why Leopold Watson bursts into “terrible, cold laughter” watching McKreager begin a skull-splitting transformation into Elder Thing. I’m not saying Watson’s become Watson-Kop, touched by the Old Ones. Only if I was the MU librarian, I wouldn’t grant this professor any further access to the Necronomicon.

Next week, Jamaica Kincaid’s “My Mother” suggests that the greatest source of disturbance may sometimes be familial. You can find it in The Weird.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.