I am both proud and slightly horrified to say that my first published novel took over a year to write, and three long years to rewrite. And that’s not counting the failed book projects that preceded it over the previous fifteen years. Even after it managed to find a publisher, the novel was simply too long, with too many characters, too many plot twists, too much exposition. Oh, and the editor who acquired it asked me to cut over 100 pages.

In the final stages of revision, I had a problem rounding out one of the major POV characters, whose motivations and decisions needed to be more compelling to match those of the protagonist and the villain. At that point, I found a solution buried in some of the movies that helped to raise me. When asked how I did it, I had a simple answer:

“I Matrixed it.”

“You did what?” came the response.

“You know. I Supermanned it.”

“What?”

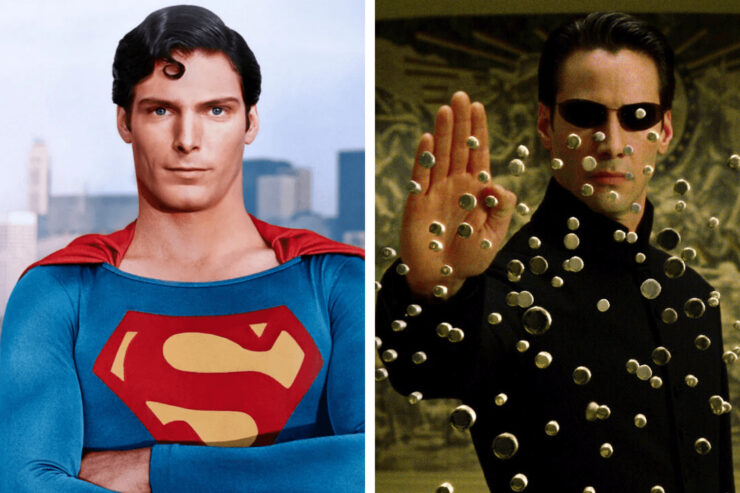

I should rewind a bit. When I think of special, transformative cinematic experiences that have changed my life, two films appear near the top of my list: Superman (1978) and The Matrix (1999). These are not surprising choices for a member of my generation, since both films set the standard in their respective subgenres. Superman is the first film I recall watching in its entirety, in the early 1980s. I saw it on a projector(!) at my babysitter’s house, followed by countless viewings on TV and video over the years. In 2018, I attended a special 40th anniversary screening, and was so overloaded with nostalgia that I thought I would pass out.

While it’s difficult to match the joy and wonder of watching Superman as a child, my experience of seeing The Matrix came close. The marketing campaign, as I recall it, revealed virtually nothing about what the Matrix actually was. So, in 1999, I went to the movies expecting a middling sci-fi action movie about virtual reality and government espionage. Needless to say, my jaw dropped through the floor during the scene when Neo discovers the truth of the Matrix.

It took me a while to realize that both movies use a nearly identical plot device to add depth to their protagonists. It took me even longer to notice that I had internalized this device in my own writing, and this realization proved to be a major breakthrough in completing my first published work.

Of course, plenty of film buffs have already analyzed how Superman and The Matrix use the classic plot structure of the hero’s journey, in which the protagonist hears a call to adventure, leaves their familiar world, and returns profoundly changed. Embedded within that structure, for both films, is a three-step formula:

- Protagonist receives major piece of advice from an authority figure.

- Protagonist receives the exact opposite advice from another authority figure—one who may be ideologically opposed, or who has a completely different perspective or priorities.

- Protagonist must choose which piece of advice to follow, thereby completing their character arc and triggering the climax of the story.

For Superman, it looks like this:

- Pa Kent tells young Clark that he was placed on Earth for a reason, implying that he should use his powers to help people.

- Jor-El—Clark’s real father—tells him that while he can lead by example, “It is forbidden for you to interfere with human history. Rather, let your leadership stir others to.”

- In order to save Lois, Clark must choose between his human father’s advice and his Kryptonian father’s advice. After wrestling with some conflicted emotions, Superman decides to reverse human history to save the woman he loves.

For The Matrix, it looks like this:

- Morpheus tells Neo that once he begins to believe in himself, and accept his role as The One, he’ll be able to fight the agents who control the Matrix.

- Cypher gives Neo far more cynical advice: “[If] you see an agent, you do what we do: run.”

- Despite all the warnings about how he’s probably not The One, and how he might get all of his friends killed, Neo chooses to fight. “He’s beginning to believe,” Morpheus observes.

This device came to the rescue when I was trying to round out the above-mentioned side character. Here I should explain that my book—Mort(e)—is about animals becoming sentient and waging war with humanity, and that the character in question is a female pit bull. Upon becoming intelligent, she adopts the name Wawa (long story), and is forced to become a hardened warrior, despite being gentle and protective by nature. By the end of the book, she finds her place among a community of exiled humans, who become her new “pack”.

I realized that Wawa’s decision was, essentially, step three in the device. I traced it back to step two, about 75 pages prior, when she meets the leader of the humans. Step one was implied, but never depicted. And so, the very last thing I wrote for this book was a mini-scene, only about a paragraph, in which a fellow animal warrior recruits Wawa to fight against the humans, and convinces her to channel her rage into the war effort. The device was there all along—maybe by accident, but maybe because I had internalized it.

There are so many things to love about this particular device. First, a good mentor-mentee conflict can reveal things like generational conflict, and how the world around them is changing. Second, it forces even a potentially passive character to act. In both Superman and The Matrix, there are long stretches in which the characters listen to info dumps. This is especially true for Neo, who understandably wanders about in a daze after his “rescue” from the Matrix. But the respective stories force a complex choice that goes beyond “go defeat the bad guy,” changing the protagonist from a mere observer to the hero.

Even better, this can serve as a worldbuilding device. Most writers would agree that the best worldbuilding relies less on exposition and more on showing how the world works, and how it impacts people. Here, we learn so much about the four authority figures who counsel the protagonist. Pa Kent is a decent man, shaped by his humble life as a farmer, so his advice to Clark makes sense. Jor-El is noble, with good intentions, but does not understand the human heart. Meanwhile, Cypher’s advice masks his own nefarious plans, while Morpheus’s position suggests that he might be a religious fanatic, obsessed with finding his messiah.1 The device therefore shows these characters to be products of their worlds, and worldviews.

Finally, though it is useful, this device—and damn, it needs a name—is no shortcut. Ideally, the first two steps should involve some ambiguity, in which the hero must determine what the advice actually means, and how to apply it. The Riddle of Steel from Conan the Barbarian (1982), for example, is just that: a riddle, open to varied interpretation. And Conan’s solution is not to choose one interpretation over another, but to create his own. Miles Morales does something similar at the end of Spider-Man: Across the Spiderverse (2023) when he announces, “Imma do my own thing.” And so, the device has many permutations. If you can think of other examples in film or fiction, let us know in the comments below…

- Earlier drafts of the script revealed that there were several people before Neo whom Morpheus believed to be The One. They presumably died while fighting the agents, which helps to explain Cypher’s growing disillusionment with Morpheus’s quest.

I remember being in college and obsessing with my friends over every single detail of the trailer for The Matrix, trying to figure out exactly what it was about. It was so, so much better than we expected.

I like this writing advice too! It takes ‘the call’ and makes it something a little more internalized rather than a literal person coming up to the protagonist and asking them to do something.

One issue is that there’s a fundamental flaw in your premise: Pa Kent and Jor-El’s philosophies are NOT incompatible with each other in the 1978 Superman film. Superman isn’t actually making a choice between them. In fact, I’d say that they directly support each other. When Jonathan Kent says that Clark is on Earth for a reason, but he doesn’t know whose reason… It’s Jor-El’s reason. Interfering with the course of human history doesn’t mean allowing someone to die, or allowing Lex Luthor to blow up half of the United States, it means allowing humanity to make their own decisions instead of making them on their behalf. Saving Lois doesn’t violate the wishes of either father.

Really, the only instance where Jonathan Kent isn’t supportive is in 2013’s Man of Steel.

Well said. This is good advice.

By strange coincidence, I wrote this advice up for myself just yesterday. It seems to parallel your own, only offers a few other ideas, and is written from the POV of jazzing up the protagonist, not necessarily a side character.

The more your protagonist wants something, the more it will draw in the audience. You can express this desire in many ways.

The first is to have the protagonist mention it, or say it out loud, or hear their thoughts about it. This is very direct and clear, but doesn’t necessarily carry a lot of emotional weight. It’s just a person talking.

The second is by choices. If you give the character opportunities for them to give up on their dream and step off the rollercoaster, put them in a position where they have to chose, and (most importantly) make going forward with their dream look like the worst of two possible choices, then you have SHOWN how dedicated your protagonist is. This has a much higher emotional appeal. It’s visceral, especially if the other choice is obviously better. “She could have been an astronaut, but instead she decided to sew socks!”

The third is by expectation. If everyone around them thinks the protagonist simply cannot be X, then it reenforces both their dedication, and makes them suddenly stronger sounding. “Wow, everyone thinks Bill can’t be an astronaut, but he just refuses to give up. What is wrong with him?”

If you cycle through these three (or more), so you hit one of each in every chapter, it will ratchet up the tension. I think.

Reminds me of my favorite two verses of Proverbs. The first one advises (paraphrased from memory), “Do not answer a fool, lest you look like one yourself.” The very next line: “Answer a fool, lest he think himself wise.” ??!?!? but WhIcH oNe ?!?! :D