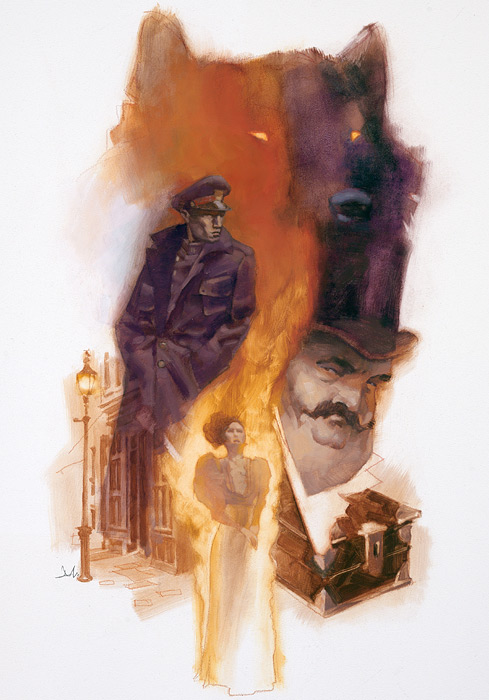

Hugo and Nebula Award-winning author Michael Swanwick presents a new fiction series at Tor.com, consisting of stand-alone stories all set in the same world. “The Fire Gown,” continues the epic tale of magic and deception in an alternate Europe of railroads and sorcery. (Intrigued? Read the first story, “The Mongolian Wizard.”)

This story was acquired and edited for Tor.com by senior editor Patrick Nielsen Hayden.

The armies of the Mongolian Wizard had just crossed into Poland when Sir Tobias Gracchus Willoughby-Quirke arrived at Buckingham, with attaché and wolf in tow. Entering the palace with uncharacteristic briskness, he was confronted by the sight of servants hurrying every which way in a manner closely resembling panic. He and his attaché exchanged glances. Had the news they had come to relay somehow preceded them?

In that instant of uncertainty, the Lord Chamberlain, a lean man with a beak like a crow’s, cried, “Tobias! Thank heavens you’re here.” Seizing Sir Toby’s arm, the Earl of Beckford leaned close and murmured, “Queen Titania is dead.” After the briefest pause to let the news sink in, he continued: “Spontaneous combustion, apparently. In her bedchamber, not an hour ago. I’m no wizard, but it looks damnably suspicious to me. This is your sort of thing, so I’m counting on you to clear it up. Establish what happened and settle the matter once and for all.”

Coming on this of all days, the queen’s death could not possibly be coincidental. But Sir Toby merely said, “Ordinarily, I would be anxious to help. But my mission today is too urgent for even tragedy to delay. I must see the king immediately.”

“Yes, yes, I am sure your business is vitally important. But if King Oberon is unwilling to see you—what then? The poor fellow is practically comatose with shock and grief and will surely remain so until the circumstances of Titania’s death have been resolved.”

Sir Toby’s face, customarily bland and amiable, twisted unhappily. “Then take me to the queen’s chambers immediately.”

The soldiers standing guard before the queen’s door parted at their approach. Inside, Sir Toby discovered a perfect circle of black where the oriental carpet had been burned to cinder and a corresponding, though softer-edged, circle of soot on the ceiling above. The smell of charred human flesh lingered in the air.

The queen must have gone up like a flare.

Sir Toby looked around the room, so clean and tidy in all aspects save for the black nullity in its center. Even the carpet was bright where it was not actually destroyed. “Where is the body?”

“It was taken to the chapel,” Lord Beckford said.

“What? This is the scene of a crime! What idiot—?”

The Lord Chamberlain threw Sir Toby the sort of look he normally reserved for bunglers or political archrivals. “King Oberon himself gave the order, of course. Which was, naturally, instantly obeyed. He has locked himself in the chapel with the cindered remains of his wife, and left instructions not to be disturbed under any circumstances.”

Grimacing, Sir Toby pinched the flesh between his eyes. Then he said, “Ritter? Tell me what you observe.”

* * *

Franz-Karl Ritter, late of the Werewolf Corps but still partnered with his wolf Freki, gazed about the queen’s bedchamber with an interest natural to a young man who knew he was unlikely ever to be in such a place again. “There don’t seem to be any closets,” he commented.

The grey-haired servant who had trailed the Lord Chamberlain as silently and ignoredly as Ritter had trailed Sir Toby said in a tone of mild reproof, “The queen’s clothing is brought in by her dresser. Therefore she does not require closets.”

Ritter spun on his heel. “The queen has a dresser? Then she must have been present when the Feuerbrunst, the—damn this language! How do you say it? The—”

“Conflagration,” Sir Toby said. “You are right, she must be questioned. Mr. Vestey, please send for Lady Anne at once.”

“But she—”

“Now, Mr. Vestey.”

Meanwhile, Ritter slid into Freki’s mind and sent the beast padding softly about the perimeter of the room. His sensorium was flooded with a wolfish richness of smell. It was dominated by the stench of death, of course, but there were other odors as well: perfumes, poudre de riz, a rose petal–scented chemical used to clean the carpet, linen sheets with just a hint of the queen’s scent upon them (which was so common a thing in his investigations that Ritter had no difficulty ignoring it), satin comforters, Irish lace, and here and there a small flake of soot that had floated free of the queen’s immolation. Plus . . . “Give me a hand moving the bed away from the wall,” Ritter commanded.

Without a murmur of protest, Sir Toby and Lord Beckford obeyed. Grunting, they three wrestled the massive piece of furniture outward.

Ritter whipped out a pair of white gloves and donned them. Then, stooping, he retrieved a small charred scrap of red cloth. “Aha! Here is the weapon—the dress itself. The cloth is woven from a thread made up of salamander’s hair.”

“Salamander? A fire sprite, you mean. Are you certain?”

“If you had the nose of a wolf, you would not doubt it. There is nothing that smells remotely like it.” Ritter drew a square of paper from his pocket and began folding it into an envelope for the cloth remnant. “Now if only we knew how it was ignited. Once set ablaze, of course, the human body will go up as a matter of course. Essential fat in a woman runs between eight to twelve percent of her body weight, which is easily enough to—” A woman appeared in the doorway and he withdrew from Freki’s mind.

“Sir? You sent for me?” The woman who followed the saturnine Mr. Vestey into the room was of aristocratic rather than beautiful features. Her hands were freshly bandaged.

Instantly, Sir Toby was all warmth and avuncular concern. “My dear Lady Anne! How terrible this experience must have been for you. Your poor hands! I trust that they have brought in a wizard from the College of Chirurgeons to place a healing spell upon them.”

“Oh, yes, he was quite gentle and very gentlemanly, too. He said that—”

“Your hands were burned in the incident?” Ritter asked.

The stricken expression returned to Lady Anne’s face. “I was just fastening the last button on Her Majesty’s new gown and it . . . she . . . the flames went up over my hands.”

“Shush, shush, my dear. It’s all right to cry.” Sir Toby took the woman into his arms, quite engulfing her, and she wept into his chest. “You have had a terrible experience but never fear, the villains responsible will be caught and punished. Your mistress, I swear to you, will be avenged.”

“The gown,” Ritter said. “This was the first time Queen Titania ever wore it?”

From deep within Sir Toby’s embrace, Lady Anne sobbed, “Yes.”

“Where did it come from?”

“It was tailored by Knopfman and Rosenberg, that’s all I know.”

“Was it commissioned by the queen?”

“I don’t know.”

“Was it a present? Perhaps from some foreign embassy?”

“I don’t know.”

“Who brought it to the palace?”

“It was Gregory Pinski.” Lady Anne lifted her head from Sir Toby’s embrace and almost smiled. “He’s the clerk for Knopfman and Rosenberg. I don’t ordinarily know the names of the delivery-men, but Gregory is such a gossip, and such a flirt. Perfectly harmless, you understand, but very amusing.”

“When this Pinski brought the gown, did you happen to mention to him, among all the gossip and flirtation, that Queen Titania would be wearing the gown on this particular day?”

“I . . . I don’t remember. It’s possible, I suppose.”

“Think hard! Did you—?”

“Mr. Vestey!” Sir Toby said loudly. “Would you do us the kindness of escorting Lady Anne back to her chambers? She has had a difficult day and I shouldn’t be surprised if her doctor wants to prescribe a sedative for her.” Then, when the lady had departed, he turned to Ritter and exclaimed. “My dear young dunderhead! You have the most damnably brusque way with women that I have ever seen in my life.”

“I get results,” Ritter said defensively. “That’s all that matters.”

“You haven’t gotten any results yet,” Sir Toby reminded him. Then, turning to Lord Beckford, “Now, whether he wishes it or not, I must see the king. The war that has been so long in the coming has at last arrived and His Majesty must begin preparing the most important address to Parliament that he will ever make.”

“The chapel is locked and guarded and the king refuses to speak to anyone.”

“Need I remind you that am a wizard? One way or another, Oberon will see me. Meanwhile, the investigation will be continued by—” Sir Toby favored Ritter with a glare “—my capable assistant.”

* * *

Hurrying across London, his wolf at his heels, Ritter saw knots of people engaged in agitated conversation, and from snatches overheard in passing, he gathered that already word had leaked that war was about to be declared. He knew that what Sir Toby wanted was for him to wrap up this matter as swiftly as possible, thus freeing his services for more important matters than the mere death of a lone woman, queen though she might be.

In this, however, if in nothing else, Ritter believed his master to be wrong. True, the Mongolian Wizard had engineered this atrocity solely in order to hobble the British people with a heartsick and indecisive king in their hour of need. The deed being done, Oberon VII would either be cajoled and scolded by Sir Toby into providing the leadership that duty required, or else he would not, in which case a way around his inertia would have to be found. So in that sense, apprehending whoever was directly responsible would accomplish little. But the villain or villains were still at large and capable of acts of sabotage that might greatly hinder the war effort. Who knew what resources they had? The Mongolian Wizard was famed for his subtlety and cunning. But he was also thorough, and he had clearly been planning this matter for a long time.

In an alley off Savile Row, Ritter hammered on the door of a dressmakers’ shop to no response. Rather than forcing the lock, he took the opportunity to drop into the neighboring tailoring establishments and ask a few questions. Local communities of specialized tradesmen always knew a great deal about one another’s lives.

So it was that when, some hours later, a slim, dark-haired woman carrying an overnight bag came up the street and, clearly startled to find the shop closed, unlocked the door, Ritter was waiting. Emerging from a doorway, he said, “You are the Jewess Shulamith Rosenberg?”

The woman studied him as one might a snake. “Who asks?”

“My name is Franz-Karl Ritter, I am attached to your government’s intelligence service, and that is all you need to know. Shall we continue this talk inside?”

Miss Rosenberg stepped within. Ritter and Freki followed.

The lady put down her bag and lit two oil lamps, revealing a tidy little dressmakers’ shop that was the essence of respectability. “Speak,” she said.

“Recently, your firm delivered a gown to Her Majesty, Queen Titania. Don’t try to deny it.”

“There is nothing to deny. Knopfman and Rosenberg are dressmakers to the queen. That fact is painted on the placard by our door.”

“Upon Knopfman’s death, your father became the chief dressmaker. You also are esteemed in this regard, though not as highly as he. Piecework is let out to various skilled local women, but your establishment is essentially a two-person operation. You and your father came here from Russia some fifteen years ago, when you were a child, and have since prospered. A year ago you took on a clerk named Gregory—or more properly Gregori—Pinski, also a Russian, to maintain your books. Yesterday you were called away to Brighton, but you told your neighbors that you would be back by mid-afternoon today.”

“It was a fool’s errand. The client who had supposedly sent for me swore she had not done so. Why are you reciting facts at me which I already know?”

Ritter slid a part of his awareness into Freki’s mind. He turned the wolf’s head so it was looking directly at the woman. Watch, he commanded silently. “You have doubtless heard that the Mongolian Wizard’s armies have crossed into Europe. Have you also heard that Queen Titania has been assassinated?”

Shulamith Rosenberg gasped. All the blood drained from her face. Freki could smell her shock. If she was faking her response, she was a very good actress indeed. “Is Tanya . . . I mean, is the queen . . . ?”

“She is dead. Moreover, the instrument of her assassination was a gown which caused her to burst into flames and which came from this shop.” Watching intently, Ritter saw Miss Rosenberg sway, eyes half closing, as if she might faint from the shock. “An establishment I now discover to be made up entirely of Russians. You can see why I am so very suspicious of you.”

To Ritter’s mild surprise, this last caused the woman’s eyes to shoot wide open and then narrow with anger.

“If you think we are Russian agents, then you know nothing about how Jews are treated in Russia! Why do you think we came here in the first place? In St. Petersburg our property was seized, our shop vandalized, offensive men made threats against our lives. It cost us all we had to buy our way to London and start over again. Yet you believe my father and I would turn on the nation that gave us safe haven out of loyalty to the Mongolian upstart? The queen was kind to me, though it was of no particular advantage to her to be so. I, in turn, loved her as dearly as any native-born subject would. You bastard! I would spit at your feet were this not my own shop.”

Withdrawing from Freki’s mind, Ritter said, “Don’t be alarmed.” The woman’s outrage was not feigned, of this he was provisionally certain. “I believe you. But I had to raise the possibility.”

The woman continued to glare as if she could stare him into stone. This interview was as good as over, and it was all his own bungling fault. What would Sir Toby do in this situation? All at a loss, Ritter could think of nothing else than to, in imitation of his superior earlier that day, open his arms and say, “It’s all right to cry.”

To his astonishment, Shulamith Rosenberg rushed forward, clutched his jacket in both her fists, buried her face in the cloth and wept piteously. Ritter put his arms around her and made vague comforting noises. For several minutes they stood thus until the woman, having cried herself out, stepped away from him.

Silently Ritter offered his handkerchief and silently she accepted it.

As gently as he could, Ritter said, “Now, Miss Rosenberg – Shulamith, I should say. I must interview Abraham Rosenberg. Your father, I mean. Where is he?”

“He ought to be here,” Shulamith said. “Perhaps he fell asleep in the back room. He’s an old man, after all.”

“Then let’s look in the back room.”

* * *

The back room was a clean and efficient workspace. One wall held nothing but crisscrossing shelves, creating diamond-shaped bins for bolts of cloth of many kinds and colors. In the facing wall, a row of windows opened on to a small garden and the brick back of another building. Light flooded through the windows and onto a white-bearded man of saintly aspect, who sat in a wooden chair, head down, as if he had just nodded off. A pair of scissors protruded from his chest.

He had been stabbed to death.

Shulamith made an urgent noise in the back of her throat and started to rush forward. But Ritter grabbed a wrist and hauled her back by force. “Touch nothing!” he commanded. “Your father is dead, do not doubt it. Freki tells me so, and in these matters a wolf is never wrong. Further, I can tell you that the deed was done hours ago, in early morning—at about the time when Pinski would have left to deliver the fire gown to the palace.” He reached out with his mind to meld with his wolf. “Which leads me to wonder where the third and increasingly most suspicious member of your business might be hiding.”

At a thought, Freki went bounding to the far end of the workroom and up a narrow stairway to the second and third floors, where the living quarters were. It took him less than a minute to determine that the clerk was not there.

Ritter released Shulamith.

Without saying a word, she sank down to kneel at the old man’s side, gazing up at his ancient face. “Oh, my father!” she cried. Then, turning to Ritter, she said, “May I kiss his hand?”

“It would do no harm, I suppose,” Ritter said, looking away in embarrassment.

Shortly thereafter, face ashen, Shulamith rose. Almost conversationally, she said, “Look. There’s the gown my father made for the queen. It hasn’t been delivered. So her death wasn’t our doing, after all.” Turning toward the dressmaker’s dummy she indicated, Ritter saw a fire-orange gown whose tailoring was unquestionably worthy of royalty. He shrugged.

“A man who can make one gown can make two. One to kill a queen. A second to deceive his daughter.”

“Monster! My father would not do such a thing. He was a good man.”

“Gnadige Fraulein, I work for your nation’s secret service, and I know far better than you what things a good man can be forced to do. Has he relatives back in the old country? Perhaps it was your own life that was threatened. There are ways around even the strongest conscience.”

Slowly, emphatically, Shulamith said, “You disgust me.”

“None of this is my doing,” he reminded her. “I am simply trying to understand the crime in as unemotional a manner as possible in order to bring its perpetrator to justice. Right now all evidence points toward the stubbornly absent Mr. Pinski. Does he live on the premises?”

“Yes, on the third floor. In the servants’ quarters.” Answering his unspoken questions, Shulamith added, “We have a cook and a maid. This is their day off.”

“For a crime this meticulously planned, I would expect nothing else.” Ritter briefly entered the wolf’s mind. Go to the front door, he commanded. Stand guard. He did not want to waste time by returning to the front to lock the door. But neither did he want strangers wandering in while he was investigating.

The wolf trotted obediently away.

“Let us see his room,” Ritter said. “And, if you will, please tell me something about Pinski’s personality.”

* * *

“There’s not much to tell,” Shulamith said as they climbed the stairs. “Pinski showed up last year after our old clerk abruptly gave notice. Father never liked him much, though he did his job well enough. A very superficial man. Always making jokes, gossiping, flirting with the ladies. Not with me, of course, I was his employer’s daughter. At any rate, I don’t think he liked women in that way. Certainly, he had no girlfriends. He liked to do magic tricks.”

Ritter paused with one foot on the stair ahead of him. “What kind of magic tricks?”

“Card tricks, mostly. Pulling coins out of ears. Clever things with bits of string.”

“Could he, by any chance, conjure up flames?”

“I never saw him do anything like that.”

Ritter started walking again. “A good pyromancer could have touched off the gown from a distance. You’re sure he never did anything remarkable with fire?”

“I’d have remembered it.” They came to the top landing. “That’s his room over there.” Shulamith turned to Ritter and in a startled voice said, “There’s smoke coming from your jacket.”

Simultaneously Ritter felt a prickling sensation, almost an itch coming from his chest. He snatched out the envelope containing a scrap of the fire gown, just in time to see it burst into flames.

It happened in a flash, leaving nothing behind but ashes and astonishment.

“Body heat,” Ritter said. “Of course. The—” he searched for the word “—conflagration was triggered by body heat. There was no need for your Pinski to be a fire-wizard at all.” He tried the door, found it locked, and took out his cigar case. Sliding a decorative rectangle of ivory, kept for this very purpose, out of its frame, he proceeded to slip the lock.

* * *

Pinski’s room was small and Spartan. There was a thin-mattressed bed with a sheet and blanket and, beneath it, an enameled tin thunder-mug. There were also a chest of drawers with a washbasin resting atop it, a plain pine wardrobe, and, pushed flat against the wall opposite the bed and looking completely out of place, a horse trough filled with water.

Ritter bent over the trough. In the water were the remnants of two bolts of reddish-orange cloth. Without bothering to doff his jacket or roll up his sleeves, he plunged his arms into the trough and pulled out both bolts. Turning, he dropped them onto Pinski’s bed. They thudded down on the blanket without leaving a stain, for they had dried instantly on making contact with the air.

“Fire cloth,” Ritter announced. “Woven from thread made of the hair of fire-salamanders.”

Shulamith touched it wonderingly. “I’ve never seen such a material.” Her fingers pinched the baize, stroked the weave. “This is extremely well-made. It must have cost a fortune.”

“We shall be lucky if it has not cost us a kingdom.” Ritter threw open the wardrobe and began rummaging through the clothes, searching the pockets, looking for documents hidden in the linings. To his side, he heard Shulamith opening and closing drawers.

Suddenly she gasped.

“A box!” she cried. “With a note attached, saying ‘For Your Hospitality.’ ”

Ritter whirled about. “Don’t—”

Too late. Shulamith had already lifted the lid.

In the instant she did so, hundreds of fleas cascaded out into the air. They leaped and hopped madly about the room, biting Ritter numerous times on his hands and face. Judging from the way she slapped at herself, they were biting Shulamith as well.

Ritter had met many genuinely brilliant men in his time and knew that he was not their intellectual equal. But he possessed great firmness of mind and was capable of reasoning things through and then acting upon his conclusions in a fraction of the time it would take his betters.

There was only one reason why a saboteur would leave a chest of fleas behind him. That was to create mischief. What kind of mischief? The only serious sort their kind carried—plague. Pinski had arranged to be well on his way out of London before those fleas were released. Therefore, Ritter was already as good as doomed to die a lingering and painful death from the disease. As were a great percentage of the population of the city, once these fleas escaped the dressmakers’ house.

Unless something were done to destroy them first.

“Quickly!” Ritter seized the topmost bolt of fire cloth and flung it, unreeling, across the room. “Help me spread out the cloth!” As Shulamith threw the second bolt into the air, he took one end of his cloth between his hands and rubbed it as hard and fast as he could. Generating heat.

He could not help reflecting that it was a pity Shulamith was in the room with him. It would have been far nobler to die alone.

Then the cloth exploded beneath his hands, knocking him backwards into the water trough and unconsciousness.

* * *

“So!” Sir Toby said. “Awake at last. You were doubly lucky. First that the blast knocked you back into the water trough, and then that your wolf came and dragged you out of it before you drowned.”

“Not . . . luck. Freki was trained to do that. To rescue me from . . . from fires and such.” Ritter’s entire body hurt horribly. “Am I dying?”

With an explosive guffaw, Sir Toby said, “You should be, sir! You should be! Half-drowned, half-burnt, and filled to the tits with bubonic plague. There are not ten wizards in the world who could have regrown those hands of yours. You are damned lucky that I had access to two of them.”

“Thank you,” Ritter rasped. “I think.” Then, “Did Miss Rosenberg . . .”

Sir Toby lost all his jollity in an instant. Somberly, he said, “No. But our forensic magicians believe she died more or less instantly, if that’s of any consolation.”

A wash of self-revulsion overcame Ritter. He had known that Shulamith was dead. Of course she was dead. It was weakness on his part to have asked. Disciplining himself to rise above his own petty concerns, he said, “And the king?”

“The grieving widower,” Sir Toby replied, “dressed in austere black, addressed a joint meeting of both houses of Parliament. He dismissed the loss of his wife in a sentence. He spoke of the darkness rising in the East. He pledged himself to the cause of civilization and promised to pay any price, bear any burden, suffer any loss in order to preserve the freedoms we hold so dear. It was the most god-awful melodramatic claptrap imaginable. But it worked. Our nation is now officially at war with the Mongolian Wizard’s empire of evil.”

“You wrote the speech yourself.” Ritter knew this for a fact.

“Yes, I did. Now sleep. The alchemist’s report tells me that your system has been cleansed of disease, and your doctors say you have every chance of recovery. Sleep. Tomorrow will be a better day.”

Ritter tried to respond to this cascade of information seriously, as a man of consequence should. But he could feel the bed falling underneath him as he himself was falling into sleep and oblivion and his adult persona did not seem to be accessible. All that he found within himself was the long-ago boy who had once thought that it would be grand fun to be a soldier. “This has not been a very satisfactory adventure,” he managed at last to say.

“No, it has not. But it could have turned out worse.”

* * *

Ritter emerged from rehab leaning heavily on a cane which, he had been assured, was only temporary. It was astonishing what the human body could accomplish when it had access to the very best medical magic in Europe.

The first thing he did was to drop by Sir Toby’s offices in the Palace of Whitehall. There he learned that the elusive Gregori Pinski had been apprehended in Dover while trying to book passage out of the country. “Our best interrogators are questioning him now,” Sir Toby said.

“If I were to plant a saboteur in my enemy’s capital, I should take great care that he know as little information useful to my enemy as possible.”

“That is indeed my policy as well,” Sir Toby said. “But it can do no harm to try. Now let me look at you! Thin as a rail, pale as an Eskimo, and weak as my grandfather a month after he died. You are immensely improved.”

“I am ready to return to work.”

“Then work you we shall! There is much to be done. But not today. Today you must have a stroll in the park, eat a good dinner, and go to sleep early in your own comfortable bed. Come by tomorrow, and I will have something for you to do.”

The spymaster went to his desk.

“Incidentally,” Sir Toby said, “despite the devastation you wreaked on its top floor, much of the Rosenberg house survived. This was among the evidence we seized. I doubt anybody would object to your keeping it.” He handed Ritter a small framed crayon portrait of Shulamith Rosenberg.

“A portrait of the Jewess? Why would I want such a thing?” Ritter said angrily.

“I just thought you might.”

Putting an arm over his shoulder, Sir Toby led Ritter to the door.

Yet when he had dropped Freki off at the kennel and gone back home to his flat, Ritter found himself almost mechanically hammering a nail into the wall and hanging the portrait upon it. Strange how the picture gathered the emptiness of the wall around itself and made all of the room look as spare and devoid of character as Pinski’s had. Why had he never hung any pictures before this?

Ritter sat down in a chair and rested his cane across his knees. He stared at Shulamith’s pale face and dark hair for a long time in silence, and then he burst into tears.

“The Fire Gown” copyright © 2012 by Michael Swanwick

Art copyright © 2012 by Gregory Manchess