- Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

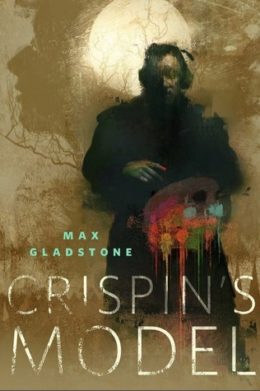

This week, we’re reading Max Gladstone’s “Crispin’s Model,” first published right here on Tor.com in October 2017. Spoilers ahead, but seriously, go read it first.

“Craquelure legions danced in the fissures of my skin. The red muscle of a peeled-back cheek was a field that grew unholy thorns, and corpses twisted in my hair, pecked by carrion birds.”

Summary

Arthur Crispin makes Salvador Dali look like an eccentric wannabee. His mother’s slow death from a mind-warping cancer has taught him a critical truth: People blind themselves to the “rot beneath our skin.” Thus he veils his work until it’s passed to the purchaser, so that its revelation will shock the unveiler and “open a gate to the truth they’ve ignored.”

His latest model, Deliah Dane, demands to see his work before starting. His still life bowl and rose are shattered, “cubist-like, through time as well as space, so in one facet the rose blooms and in another it’s rotten…But that doesn’t capture the twisted, callous distance of the effect.” She wonders what Crispin will make of her. The thought is at once disgusting and exciting. Not that she’ll know, since one of his rules is she’s never to see his portraits.

Deliah models to support her own ambitions as actor and writer. Modeling pays twice what the restaurant does, gives her extra days for her own work. And another perk—in the long, motionless, silence, “thoughts stretched long and memories ran like rivers.” Afterwards, she writes and writes, and some of what she writes she thinks good, and so does her agent.

But modeling for Crispin is different. It hurts more. Her memory-stream doesn’t flow. In fact, time doesn’t seem to pass at all.

Crispin invites Deliah to the gallery showing of their first four paintings. The upscale affair is packed with the conspicuously wealthy, and Crispin in a corner in his usual shabby garb. The coldness with which he implies that Deliah is there as part of the show makes her storm off, only to be collared by Shannon Carmichael, her agent. Has Deliah seen them yet? Meaning the four paintings shrouded in black velvet booths, to be viewed in full light only by the one who can afford to buy them. Buy Deliah, as Crispin implied.

Shannon hustles her into the booth labeled “Face.” At least no one’s going to recognize her. Crispin has peeled apart her face into something “fissured and fused and melted and monolithic, distorted into something more real, full, there than I had ever felt. “My painted eyes were pits…charged with sick galaxies of staring, slitted orbs, space filled with the piping of a mindless master whose music was a scream.” She reaches, saved only by the memory of a teacher’s field trip reproach: Deliah, don’t touch.

She staggers, sweating, from the booth. Shannon introduces her to Morrison Bellkleft, who wants to buy all four paintings. Deliah flees the gallery.

At their next session, Crispin greets Deliah with news: Bellkleft bought the paintings for a hefty sum. They don’t look like me, Deliah challenges. Oh, and just because Crispin’s a rich white man doesn’t mean he’s the only one who has “an inside line on how messed up shit really is.” Deliah knows truth, too. Yet in Crispin’s plea that she sit for one more painting, she hears enough sincerity to say yes.

Crispin poses her on a red leather divan, caught at the moment of waking. The posture hurts. Worse is the immense pressure she feels from below, the truth Crispin sees through her, “a blasted, writhing, whimpering world.”

Shannon invites Deliah to Bellkleft’s unveiling. She arrives as a hurricane approaches the city, to see fire shooting from Bellkleft’s tenth floor windows. Inside Bellkleft’s apartment, smoke roils from the paintings, in which green flames surround “dark writhing depths.” What waits past the dark will be grotesque, yet also beautiful, and she steps toward it. Shannon’s unconscious body is mere annoyance until the painting crumbles and Deliah snaps out of its spell. She hoists the agent onto her back. Morrison’s absent, but clawed, inhuman footprints cover the sooty carpet. Wings and eyes flicker outside the broken windows.

Crispin’s grimly gratified to hear what happened. They’re so close now to the place beyond death, the root of the horror, where they lie sleeping. Will Deliah pose? She knows she shouldn’t, but she’s dived so deep with him now, she fears she’ll drown rising alone.

Crispin paints, whispering incomprehensible words. Tension grows in both artist and model. Rain lashes the window, and branches claw it, except there are no trees outside, they’re too high up. These are the insectile things released from Bellkleft’s paintings.

She must see what they’ve come to see. She struggles out of her pose, ignoring Crispin’s commands. When he tries to grab her, she head-butts his nose and stands before “this creature his mad beholding had chiseled from raw space, cancer and mother and blood, swollen, breaking open, shaking ropes of flesh, hair a coil of serpents….” It’s not her, and yet, he’s made her image “door and mother of monsters.”

The painted figure heaves and cracks. Deliah streaks paint across it. Crispin wrestles her away, but she forces him to see the flying monsters, the greater monster still birthing itself from his painting. For the first time, Crispin looks scared.

Deliah drags him to the canvas. To seal the Mother in, he must paint Deliah as she IS, not as he SEES her. Crispin takes the brush and goes to work. Something howls.

Over many weeks they continue painting Deliah over the Mother, and they talk about themselves and their lives, just as strong a counterspell. Morrison Bellkleft’s still missing, but Agent Shannon’s recovering and likes what Deliah’s writing. One nagging worry: Where did those flying horrors go? Did they die, or are they waiting for someone else to birth their mother? One thing’s sure. There are monsters. They’re out there still.

They have no world but ours.

What’s Cyclopean: Best neo-adjective: “Mama’s plumbed Michael Baysian depths of subtlety.” Best traditional adjective: “craquelure legions.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Deliah’s initial reaction to Crispin’s no-looking rule: “So, what, you paint me as subhuman and I don’t get to call you racist afterward?”

Mythos Making: Someone at the gallery opening says “something about ‘jog’ and ‘Sabbath’.” Wrong deity, if Deliah’s portrait shows “space filled with the piping of a mindless master whose music was a scream.”

Libronomicon: Deliah is writing a play; posing for Crispin both inspires and warps her story.

Madness Takes Its Toll: After Deliah’s agent sees Bellkleft’s paintings in full light, a few months later her lung’s mostly better. Her mind, too.

Buy the Book

Fathomless

Anne’s Commentary

Crispin, why, you’re no Pickman, even though your blood might flow as blue on the human side. There’s no inherent ghoulish streak in you. Why, you can’t even reliably maintain your cruel and indifferent front—a warm smile will escape you at the awkwardest of times. You’re no wholly pitiable victim like Erich Zann either, for you sold those four paintings to Morrison Bellkleft knowing they posed a grave danger to the “unveiler.” And, yes, you don’t get off morally unbesmirched just because Morrison was a filthy rich old white man. I don’t know. You definitely go too far, old sport, and yet you have your sympathetic points, the Mom thing and all. Just, come on, carrying it to the extreme of since the universe was rotten to your mother, it must be rotten to the core, all monsters all the way down?

Except you may be right, mayn’t you….

Anyway, the most interesting thing is how you don’t get killed in the end, sucked right into that painting of yours or carried off by the frustrated insectile children of the Mother denied them. On the physical side, you get away with a broken nose. On the mental side, you actually improve! Start opening up, listening to others, socializing again! This, now, is a truly non-Lovecraftian denouement.

Deliah Dane, obviously, you are no Pickman’s model ghoul, all rubbery and mouldy and content to hang out in sewers until wanted. You, I think, are the narrator of the story because you’re a take on a Lovecraft—actually Lovecraft/Bishop—character many of us have longed to see take control and fight back. Yes, that’s right. That one-time artist’s model Marceline Bedard, later Marceline de Russy of Riverside, she of the Medusa coils. In which case, eureka, wouldn’t Crispin stand in for “decadent” artist Frank Marsh, who explains his desire to paint Marceline to her husband Denis de Russy thus: “I see something in her—or to be psychologically exact, something through her or beyond her—that you didn’t see at all. Something that brings up a vast pageantry of shapes from forgotten abysses, and makes me want to paint incredible things….”

Corresponding details fall in place—Marceline and Deliah pose nude on divans; both painted figures have serpentine hair; both artists hide their work from their models; both artists strive to depict “the ultimate fountainhead of all horror on this earth,” and too well achieve their goal. Easy to list these obvious similarities. What’s hard beyond my time and space to discuss here, and indicative of how rich and provocative a story Gladstone has crafted, are the echoes between “Medusa’s Coil” and “Crispin’s Model,” the consonances and dissonances, the weight of race in the scales of horror. Does Frank Marsh mean that friend Denis will be destroyed when he learns from Frank’s painting that Marceline is an actual demon, or as “Medusa’s” narrator assumes, when Denis learns she is a “negress”? Is Deliah right to challenge Crispin when he says she can’t look at his depictions of her, lest she be offended? “So, what,” she says, “you paint me as subhuman, and I don’t get to call you racist afterward?”

And then, to save the world, Crispin must paint Deliah as she is, in the true color of her skin, not the sick kaleidoscopics of the Mother.

Just starting on the interestings here!

Buy the Book

Deep Roots

Ruthanna’s Commentary

We’ve gone through a lot of riffs on “Pickman’s Model.” No surprise, since it’s not only one of Lovecraft’s most evocative stories, but offers writers the irresistible opportunity to write about the process of making art. And about the idea that, through making art, we can show truths about the world that no one would otherwise be willing to face. Perhaps, even now, our art is Too Much For the Mind to Bear. But it really does make for good stories, and writing about painting provides the opportunity to describe masterpieces without having to replicate them—a particularly smart idea for images of the Pickman school.

“Crispin’s Model” is my absolute favorite of the Pickman follow-ons. It’s a response rather than a replication or a sequel. It has layers, peeling back words to expose muscle and bone and void.

Top layer: Lovecraftian, and having fun with it. Gladstone gets in a few digs at the original, from “Saying you can’t say something, that’s one of the old tricks, right?” to giving Crispin “an accent that would have told someone from Boston or Providence a lot about his parents and the pedigree of his dog”. Wry self-reference, too, as Gladstone is himself Bostonian. And characterization of Deliah, come up from Georgia and not intimately familiar with the level of diversity that can be found even in Yankee territory.

Then darker Lovecraftiana. The gorgeous twist of “A hurricane is an ocean come walking.” The familiar play of attraction/repulsion. The sideways references to Mythosian deities who don’t directly appear on the page, from someone mentioning Yog-Sothoth at a gallery opening to describing Deliah, separately, as both gate and key.

There’s another layer. Deliah is the gate and the key—and her not-portrait is one of a monstrous mother, welcomed in turn by her monstrous children. Painted by Crispin, child of a mother eaten by monsters, or made monstrous…

Then we get into where monsters come from in the first place. Are they simply made visible, or summoned, or birthed? Crispin thinks that he’s like Pickman, simply showing people a horror that already exists under the surface. But the horror’s in his eye, not the world. He’s making it or summoning it or both, adding something that wasn’t there before. And we do that with our art, walk the fine line between making visible some truth about the world, and adding something to it, and sometimes it’s impossible to tell which we’re doing—and sometimes everyone but us can tell which we’re doing.

Getting back to Lovecraft’s favorite emotion of mixed attraction and repulsion, another thing that Gladstone handles especially well. I think this may also be something that’s particularly persuasive when applied to art, because art is where most of us experience it most often. (Except for those of us who spend inordinate amounts of time working out devil’s deals with mind-stealing aliens.) Here, we see that conflict from many angles at once, like Crispin’s grotesque cubist rose: in the model, the painter, the audience, ourselves.

Attraction/repulsion, works particularly well when writing about art since that’s where most of us actually experience it. Particularly nice here. And different aspects of it: in the model (the fulcrum, the gate), in the painter, in the audience, in the reader. Deliah’s experience is particularly compelling—not only getting drawn into someone else’s artistic vision (metaphorically and literally) but into the power of being the gate, the line that transforms increate to creation. We see our first glimpse when she relishes the power to force Crispin to show her a still life—to sacrifice it to her, in fact.

And she’s the one who has the power at the end, too, who forces Crispin to look at her. And later to talk to her, just as important. How else are we to defeat monsters?

Next week, in Stephen King’s “Gray Matter,” we’ll discover that some things really can transform a person into an eldritch abomination.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Dreamwidth, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.