Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months more than a year to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the 61st installment.

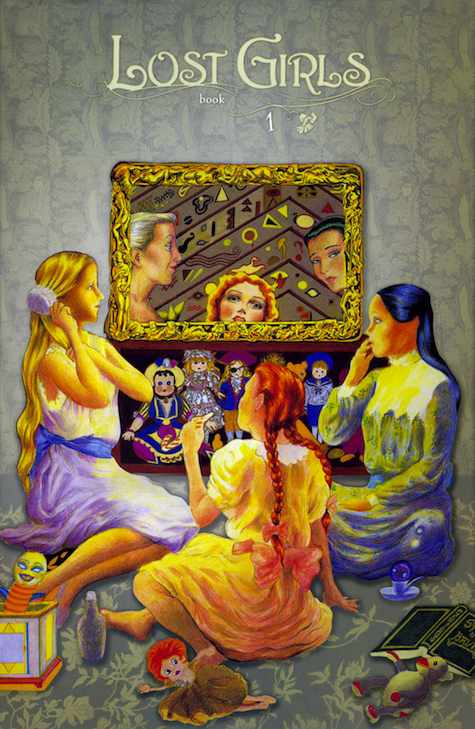

In 2006, Top Shelf Productions released a gorgeously-designed, three-volume hardcover set of books in a handsome purple slipcase. It is, by far, the most elegant presentation of any Alan Moore project, and yet the contents of the books feature Moore’s most pornographic comics. That was what he was aiming for: pure pornography, his way.

Lost Girls began as a serial in Steve Bissette’s Taboo anthology, starting with issue #5 in 1991, and only six of the eventual 30 eight-page chapters were ever released in that format. It wasn’t until the 2006 Top Shelf release that readers even had a chance to see the completed project, and between the time it began and the time it ended, over 15 years later, Alan Moore and Lost Girls artist Melinda Gebbie began a romantic relationship that ultimately led to marriage.

That would seem to indicate that Lost Girls is the most personal of Alan Moore comics. It’s certainly the most intimate, with graphic depictions of sex delicately drawn by his longtime collaborator and current wife. But its pornographic nature keeps it from being widely discussed alongside Moore’s other highly-regarded books. The expensive, slipcased version of Lost Girls reportedly sold over 35,000 copies, even before Top Shelf released a one-volume edition that surely added to that total, and yet it’s a project that’s brushed aside with embarrassment or praised as an astounding feat of artistry by Melinda Gebbie but not examined in the depth that Moore’s other work so often encourages.

But I think that’s fair. Because Lost Girls is unrepentantly, defiantly pornographic, and even as Moore and Gebbie push the boundaries of that genre towards what might be perceived as a deconstruction of its forms, it’s still a 240-page story filled with page after page of explicit, often taboo, sex, and no matter how many variations the creative team throws into each scene, there’s an oppressive tedium to the pornographic excess.

It doesn’t lack intelligence, and stylistically and thematically, Lost Girls is far more ambitious than whatever you might imagine as “just a porn comic,” but it’s still ultimately a comic about three women, of various ages, having sex with each other repeatedly, and flashing back to other times they had sex with other people, repeatedly, and when they’re not doing that, they’re having sex.

It’s overly simplistic to compare pornography to superhero comics, even though Moore himself has been a pioneer in blurring that line in the past, but Lost Girls is the pornographic equivalent of a superhero epic where 200 of the 240 pages are just one fight scene after another. No matter how well choreographed, or how well-drawn, or how symbolic the individual moments, it’s still a slog to read through so many variations on the same thing. The greatest sin of Lost Girls isn’t that it’s filled with images that could get the book confiscated at a customs checkpoint, its greatest sin is that, as a story, it’s incredibly boring to read.

Lost Girls (Top Shelf Productions, 2006)

Alan Moore’s formalist tendencies are on keen display in this book—and, yes, I’ll refer to it as a single book even though my 2006 copy is the three-volume edition. The opening and closing use the same static camera to show events reflected in a mirror. Six panels per page. Eight pages per chapter. That’s not what makes it a dull read, though. The formalist structure—not every page is six panels, but every chapter is a crisp eight pages—can be thrilling at times, and like many of Moore’s best comics, Lost Girls is an artistic showcase. Melinda Gebbie not only does the best work of her career on this project, but her mixed media approach does give this book a unique look. It’s soft and full of light and air and if you flip through it and somehow miss the pages of explicit sex—which would be basically impossible—then you might mistake this for an innocent but beautifully-illustrated picture book. Or a strange and enchanting work of art in comic book form.

And it does tend toward that, at times. But at its core, it’s the story of the sexual explorations of three fictional characters against a backdrop of war. And the sexual explorations get the most attention.

Actually, let me just turn it over to Alan Moore, and let him describe his approach in the words he uses in his interview from the indispensable The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore with George Khoury:

“I noticed that if comics ever did approach erotica, then it was only either with a veneer of humor or with a veneer of horror,” says Moore. “It was all right to use sexual elements in a horror story to make the horror more visceral. It was all right to use sexual elements in a humorous story because then it was making a joke of sex. And while both of these are valid, my usual reaction to sex is neither to laugh or scream. To most people it’s just sex: it’s enjoyable for what it is.”

Fair enough. And that approach to sex isn’t just a problem in the comic book medium. Sex in Hollywood movies is often turned into a locker room joke or exploited for lascivious purposes in slasher films or thrillers. In American literature, as Leslie Fiedler once famously pointed out, the repression of sexual desires is so strong that real considerations of love are replaced with a fascination with death. Thanatos replaces Eros. That sort of thing. But in terms of cinema, there is a substantial history of sex-for-the-sake-of-sex, in the abundance of pornography. And in terms of prose works, it’s not difficult to find plenty of what is so genteelly known as erotica. But in comics, not so much. Most comics featuring explicit sexuality have been Robert Crumb-style comedy antics or violent horror comics like David Quinn and Tim Vigil’s Faust or Howard Chaykin’s Black Kiss.

Moore’s right about the lack of sex-because-sex-is-enjoyable comics. But, of course, he couldn’t write a comic that was merely that, either. He had to couch it in literary allusion and Modernist symbolism, which isn’t necessarily a bad idea on its own. Here’s what he tells George Khoury about the specific origins of Lost Girls, once he started thinking about how to approach pornography in comics:

“I thought it might be interesting to sexually de-code the Peter Pan story,” Moore says. “I was thinking about Freud’s insistence that to fly in dreams is a sexual symbol and I started thinking about Peter Pan and Wendy, and how Wendy is at that kind of age where she probably would be starting to experience sexual feelings.”

Once Moore had the idea for using Wendy Darling in the story, he started looking around for other literary figures to bring into the book, inspired by an early conversation with Melinda Gebbie. “Melinda happened to say, quite by chance that she, in the past, had written a couple of stories that had three women as the main characters. She said she liked the idea of having three woman as protagonists. So consequently that was when it all crystallized; Melinda’s three women idea collided with my Peter Pan idea and I suddenly thought, well, what if you have three women? What if Wendy was just one of them? Who would the other two be?”

Mind you, this pre-dates (and reportedly inspires) his literary team-up comic The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, so at the time he was planning Lost Girls, the act of bringing characters from multiple novels together into one story was not something that he was known for the way he is now. But once he had Wendy in mind, he looked at other female protagonists and considered Alice, from Alice in Wonderland, and Dorothy Gale, from The Wizard of Oz. Lining up their first appearances and calculating their various ages, he realized that he had plenty to work with in terms of contrast, and a historical backdrop that provided built-in opportunities for conflict.

“We’ve got three women of different ages with interesting differences between them,” says Moore. “Alice is kind of upper class. Wendy is distinctly middle-class, and Dorothy is rural. She’s blue-collar, she’s working class. There were all sorts of little aspects that suddenly came up, and 1913, that was when the war was picking up and this was a very interesting time in Europe, so all of those factors came together.”

All of that sounds completely fascinating, and Moore and Gebbie spend much of Lost Girls playing with the social class and age differences between the characters, and the specter of the Great War looms over everything. But ultimately, all of those ambitious ideas and noble literary goals are overshadowed by the bombardment of sexual positions throughout so many of the chapters of the book.

In effect, the story becomes almost comical, though Moore says he didn’t intend it that way, and Gebbie presents things beautifully. But it can’t help but be comical, when every conversation turns to an explicit sexual encounter, like a parody of pornography, rather than something that seems plausible, even within its own fantastical world. And even as the first half of the book is riddled with sexual escapades, the second half of the book becomes even more outrageous, as the men depart, leaving the women and servants to have the kind of almost non-stop orgy that would put Bacchus to shame.

It just gets to be too much, and then it stays that way until the final chapters when things take a brutal turn and the violence of war encroaches on the sexual idylls.

But with the backdrop of war, such an ending was inevitable, so all we’re left with is whatever enjoyment we can get out of the relationship between the three women (a respectable amount), whatever appreciation we can get out of Gebbie’s artistry (plenty), and whatever titillation we can get from the nonstop sex (it’s tiresome, mostly). I wouldn’t call Lost Girls a failure, but there’s not as much substance to it as I remembered, and I didn’t remember that it had an overwhelming amount of substance.

Ultimately, it’s best to consider the book in light of Moore’s own judgments on pornography. He says pornography is “mostly ugly, it’s mostly boring, it’s not inventive.” Lost Girls isn’t ugly, though the involvement of three female characters from children’s literature might make it particularly vile in its willingness to embrace taboo. Lost Girls is inventive, at least artistically, with Gebbie unafraid to employ different visual styles to mimic both children’s book illustrations and Victorian erotic drawings and everything in between. But that still doesn’t it cure the book from being endlessly boring and repetitive, like most pornography.

Sex may be enjoyable for what it is, as Moore has said, but that doesn’t mean we want to stare at it over and over and over again until the soldiers show up to smash the enchanted mirror and wake us up to the stark realities of the 20th century.

NEXT TIME: Alan Moore teams up with his daughter to write a kind of Watchmen for British superheroes in Albion, with mixed results.

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.