Here’s a fun little thing you can try at your next family gathering (sometime in, oh, 2022? ’23?). Get people talking about Looney Tunes. Get ‘em talking about their favorites, about how much they love the meta humor of Duck Amuck, or the sophisticated satire of What’s Opera, Doc?, or the trenchant irony of One Froggy Evening. And when the question comes around to you, you just square your shoulders, look them straight in the eye, and proudly proclaim, “Nothing’s better than The Great Piggy Bank Robbery.”

You can then relish the silence, one so profound it would be as if you had just said, “You know, the good thing about hitting yourself in the head with a two-by-four is…”

A caveat here: This only works with people who have a conventional appreciation of Looney Tunes (and its companion series, Merrie Melodies)—one spawned, say, of Saturday mornings and after-school afternoons spent in the company of Bugs, Daffy, and the gang, or, later, from an intimate acquaintance with the Cartoon Network’s earliest offerings. If you pull this gag on knowledgeable cartoon fans, you’ll only be met with nodding approval. If you try it with professional animators, you’re likely to be ostracized for having the audacity to think you’re pulling a fast one on them.

And that’s the interesting thing about The Great Piggy Bank Robbery. It’s one thing to be loved by the general public, it’s another to be exalted by the experts in your field, as Piggy Bank is. So much so that its techniques are still being applied in cartoons today. So much so that animators have examined its sequences frame by frame to unlock the mysteries of its magic.

Which is, to some extent, an elusive goal. Sometimes the planets align in just the right way, and the conjunction’s gravitational pull steers all the elements into the perfect position. In Piggy Bank’s case, it was an amalgam of direction by Looney Tunes’ resident anarchist (even by Looney Tunes standards) Bob Clampett, inspired animation, most notably by the amazing Rod Scribner, gorgeous backgrounds credited to Thomas McKimson and Philip DeGuard, pitch-perfect acting by voice genius (and master screamer) Mel Blanc, plus the influence of parent company Warner Bros.’ hardboiled crime thrillers, and the advent of the cynical, shadow-subsumed genre that would become known as film noir.

And you’d hardly know it from the first few seconds of the cartoon, which are devoted to a serene pan over a bucolic, farm setting. But enjoy the view while you got it, boyo, because it’s the last peaceful moment you’ll have in the next seven minutes. Cut to an anxiety-ridden Daffy Duck, unable to stand still as he keeps watch over his mailbox. His very first line is an anguished scream: “Thufferin’ thuccotash, WHY DON’T HE GET HERE?” (Fun fact: if it feels odd that Daffy is dropping Sylvester the Cat’s catch phrase, it’s because Blanc used the same voice for both characters. Daffy’s is just sped up.)

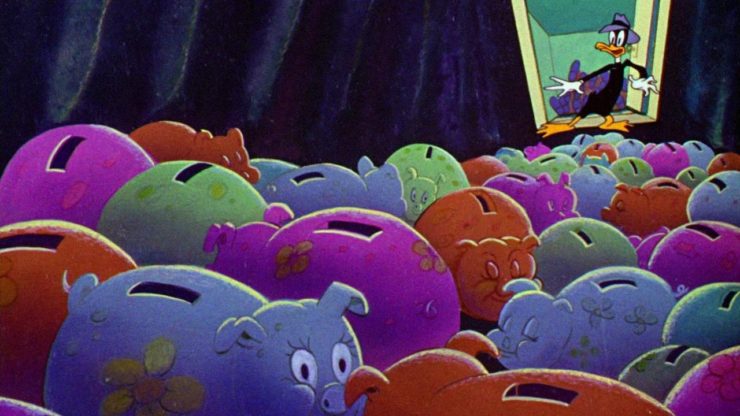

And what could the mailman be bringing to provoke such anticipatory anguish? This month’s Harry and David shipment? A royalty check? (With Schlesinger in charge? You kidding?) Nope, it’s the latest issue of Dick Tracy Comics, which, once it arrives, Daffy grapples as if it was the Maltese Falcon, and then pores over with the intent focus of Nic Cage searching for a treasure map on the back of the Declaration of Independence. So rapt is the duck with the gumshoe’s adventures that he inadvertently knocks himself out while pretending to fight off a gang of thugs, and, unconscious, dreams that he has become Duck Twacy, “famous de-tec-a-tive,” on the trail of the miscreants who have stolen his city’s piggy banks.

Buy the Book

The Chosen and the Beautiful

Looney Tunes in general, and Bob Clampett in specific, were no strangers to dream sequences. The director had used dream-logic to indulge his most surreal impulses—confusions of space and time, scenery that existed beyond the bounds of logic or gravity, and imagery that pushed the limits of animation to, and past, its borders (in The Big Snooze—planned by Clampett and completed by colleague Arthur Davis—a nightmare-plagued Elmer Fudd is tortured by a squiggly chorus line of rabbits that wouldn’t have looked out-of-place during Fantasia’s more stylistic moments). That manic impulse is here—particularly in the sequence’s staccato editing—but in a more controlled fashion, the noir influences grounding the action in a strong narrative.

So, yes, unhinged wackiness ensues, including the villain’s secret hideout being advertised with a bunch of neon signs, Daffy following a trail of footprints up one wall, across the ceiling, and down the other (“Nothing’s impossible to Duck Twacy!”), and a cameo by Porky Pig—inexplicably wearing a handlebar mustache—as a streetcar conductor. But the mise en scene eschews cartoony whimsy for atmospheric darkness—the settings distort in weird and threatening angles, while the shadowy backgrounds anticipate the use of airbrushing on black paper that would become the trademark look for Batman: The Animated Series.

And what goes on in front of those backgrounds is nothing short of amazing. Rod Scribner may have been Warner’s wildest animator (and maybe just wild in general—legend has it that he burned his own house down). Here, he’s given a chance to pull out all the stops. When Daffy exalts over Dick Tracy’s prowess, his head and torso project out aggressively toward the camera, practically landing in the audience’s lap. As Twacy notes the onset of a “piggy bank crime wave,” the monologue is captured in tight close-up, with each frame metamorphizing the face into increasingly abstracted forms, the spittle of his lisp curlicuing out in delicate filigrees.

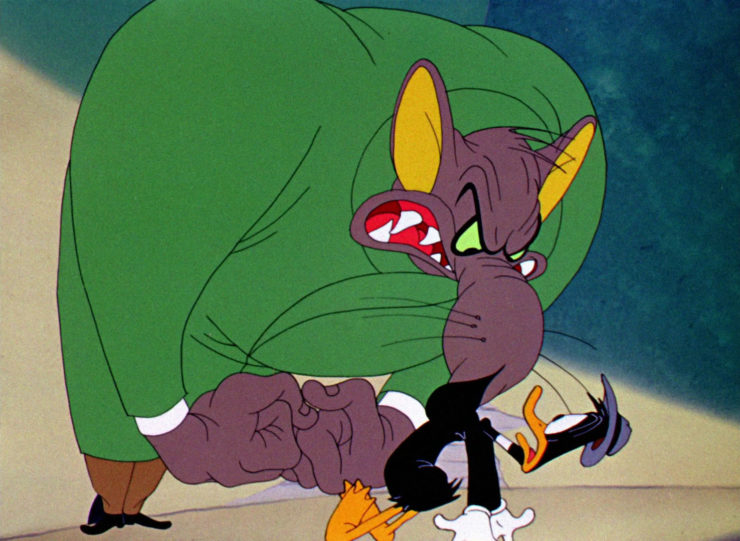

In fact, whatever situation gets set up in this cartoon, the animators respond with the most extreme solution. When Daffy summons the criminal Mouse Man for a confrontation, what emerges from a miniscule hole in the wall is a towering monster that would give David Cronenberg fits. (“Go… back… in again,” the gumshoe sheepishly requests, to which the behemoth immediately complies—my favorite gag.) When the criminal Rubberhead begins literally “rubbing” Daffy out, the duck’s line, “It’s fantastic. And furthermore, it’s unbelieva…” is cut off as he completely vanishes, and can only be resolved by having him pop his head out of a closet to croak, “…ble.” (Everybody else’s favorite gag.) And when the assembled gangsters then bum-rush Daffy, cramming him and themselves tightly into that closet, the animators engineer the duck’s escape by squiggling his component parts out from in-between the evildoers’ packed bodies.

So fearless are the cartoonists in pushing the envelope that Piggy Bank manages that rare dance between comedy and genuine horror. Where Jordan Peele in his films has found a way to leverage absurdity so that it shades into terror, Clampett and team take a reverse turn, manipulating the grotesque to generate laughs. The aforementioned Mouse Man, in his design and animation, is pure nightmare, but the rapid-fire pacing of his emergence from the hole and subsequent, unceremonious retreat—followed by Daffy’s grimacing take to the camera—pushes the entire moment toward the ludicrous. When Daffy sprays the closetful of criminals with machine-gun fire—the action, as rendered, shocking in comparison to all the times Elmer Fudd fired off his wimpy ol’ shotgun—Clampett angles his camera up from the floor to capture close-in the domino-fall of corpses in all their grisly details. Except not so grisly as just plain silly, with the lead victim licking a candy cane, the fall of the villain Snake Eyes punctuated with the sight of his dice-shaped eyeballs bouncing ridiculously back up into frame, and the sheer number of cadavers—and the escalating speed of their tumble—pushing toward the absurd.

It would be enough for one cartoon to leave you breathless at its pacing, its bravado, its artistry. What cements The Great Piggy Bank Robbery’s status as, at least, one of the greatest Looney Tunes of all time—if not the greatest—is that its influence is still being felt in cartoons today. Chuck Jones’ The Dover Boys at Pimento University or The Rivals of Roquefort Hall may have innovated the technique of flash-animating a character’s movements from one dramatic pose to another, but Piggy Bank showed its disciples how to weaponize the technique for its full, eye-assaulting effect. Any Teen Titans Go! or Spongebob Squarepants episode that pauses the action to share a static close-up of something rendered in gruesome detail echoes Piggy Bank’s exquisitely portrayed survey of the Twacy rogues gallery. And anytime an animated character twists from its set model into strange, abstract forms, Rod Scribner’s evocative hand is in evidence. (In addition, Clampett proved that noir ambiance worked just as well in color, and did it twenty-eight years before Roman Polanski’s Chinatown.)

The Great Piggy Bank Robbery may have started as just another entry on the Warner cartoon production schedule (and, in fact, as Clampett’s penultimate directing gig before leaving the studio to blaze new trails with TV’s Time for Beany), but everyone involved invested a level of commitment that turned it into a role-model for future animators. It’s not just a great cartoon, it’s also the past, present, and future of the animation art.

…A bold declaration, I know. Maybe you feel differently about The Great Piggy Bank Robbery, or think another cartoon should stand at the pinnacle of the field. You’re wrong, but let’s hear you out. Make your case by commenting below!

Dan Persons has been knocking about the genre media beat for, oh, a good handful of years, now. He’s presently house critic for the radio show Hour of the Wolf on WBAI 99.5FM in New York, and previously was editor of Cinefantastique and Animefantastique, as well as producer of news updates for The Monster Channel. He is also founder of Anime Philadelphia, a program to encourage theatrical screenings of Japanese animation. And you should taste his One Alarm Chili! Wow!