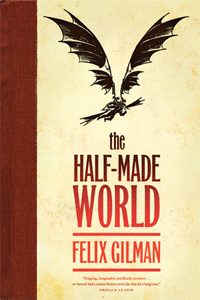

We hope you enjoy this excerpt from The Half-Made World, a fantastical reimagining of the American West influced by steampunk, the American western tradition, and magical realism. For another taste of this world, check out Felix Gilman’s short story “Lightbringers and Rainmakers.”

CHAPTER ONE

1889

THE DEPARTURE

One fine spring afternoon, when the roses in the gardens of the Lodenstein Faculty were in bloom, and the lawns were emerald-green, and the river was sapphire-blue, and the experimental greenhouses burst with weird life, the professors of the Department of Psychological Sciences met in the Faculty’s ancient August Hall, in a handsomely-appointed upstairs library, where they stood in a little group drinking sherry and saying their goodbyes to their colleague Doctor Lysvet Alverhuysen—Liv, to her friends—who was, against all reasonable advice, determined to go west.

* * *

“You’ll fall behind, Dr. Alverhyusen.” Dr. Seidel shook his head sorrowfully. “Your work will suffer. There are no faculties of learning in the West, none at all. None worth the name, anyway. Can they even read? You won’t have access to any of the journals.”

“Yes,” Liv said. “I believe they can read.”

“Seidel overstates his argument,” Dr. Naumann said. “Seidel is known for overstating his arguments. Eh, Seidel? But not always wrong. You will lose touch with science. You will rip yourself from the bosom of the scientific community.”

He laughed to show what he thought of the scientific community. Handsome and dark of complexion, Dr. Naumann was the youngest of the Faculty’s professors and liked to think of himself as something of a radical. He was engaged in a study of the abnormal or mis-directed sexual drive, which he regarded as fundamental to all human activity and belief.

Liv smiled politely. “I hope you’ll write to me, gentlemen. There are mail-coaches across the mountains, and the Line will carry mail across the West.”

“Hah!” Dr. Naumann rolled his eyes. “I’ve seen the maps. You’re going to the edge of the world, Dr. Alverhuysen. Might as well hope to send mail to the moon, or the bottom of the sea. Are there mail-coaches to the moon?”

“They’re at war out there,” Dr. Seidel said. “It’s very dangerous.” He twisted his glass nervously in his hands.

“Yes,” Liv agreed. “So I’ve heard.”

“There are wild men in the hills, who are from what I hear only very debatably human. I saw a sketch of one once, and I don’t mind admitting it gave me nightmares. All hair and knuckles, it was, white as death, and painted in the most awful way.”

“I won’t be going into the hills, doctor.”

“The so-called civilized folk are only marginally better. Quite mad. I don’t make that diagnosis lightly. Four centuries of war is hardly the only evidence of it. Consider the principle factions in that war, which are from what I hear not so much political entities as religious enthusiasms, not so much religion as forms of shared mania. . . An irrational cathexis. A psychotic transference of responsibility from themselves to inanimate but symbolically charged objects that. . .”

“Yes,” she said. “Perhaps you should publish on the subject.”

If she listened to another moment of Dr. Seidel’s shrill voice she was in danger of having her resolve shaken.

“Will you excuse me, doctors?” She darted quickly away, neatly interposing Dr. Mistler between herself and Seidel.

It was stuffy and dusty in the library; she moved closer to the windows, where there was a breeze and the faint green smell of the gardens, and where Liv’s dear friend Agatha from the Department of Mathematics was making conversation with Dr. Dahlstrom from the Department of Metaphysics, who was terribly dull. As she approached Agatha waved over Dahlstrom’s shoulder and her eyes said help! Liv hurried over, side-stepping Dr. Ley, but she was intercepted by Dr. Ekstein, the head of her Department, who was like a looming stone castle topped with a wild beard, and who took both her hands in his powerful ink-stained hands and said: “Dr. Alverhuysen—may I abandon formality—Liv—will you be safe? Will you be safe out there? Your poor late husband, rest his soul, would never forgive me if I allowed. . .”

Dr. Ekstein was a little sherry-drunk and his eyes were moist. His life’s work had been a system of psychology that divided the mind into contending forces of thesis and antithesis, from the struggle of which a peaceful synthesis was derived, the process beginning again and again incessantly. Liv considered the theory mechanical and unrealistic.

“I have made my decision, doctor,” she reminded him. “I shall be quite safe. The House Dolorous is in neutral territory, far from the fighting.”

“Poor Bernhardt,” Dr. Ekstein said. “He would haunt me if anything were to happen to you; not, of course that I would expect that it would; but if anything were to happen. . .”

Dr. Naumann insinuated himself. “Hauntings? Here? Sounds like you’ll miss all the real excitement, Dr. Alverhuysen.”

Ekstein frowned down on Naumann, who kept talking: “On the other hand you won’t be bored—oh my no. No place out there is neutral for long. No matter how remote your new employer may be, soon enough you-know-what will come knocking.”

“I’m afraid I don’t know, Dr. Naumann. I understand things are very turbulent out there. Excuse me, I must—”

“Turbulent! A good word. If you cut into the living brain of a murderer or sex-criminal you might say what you saw was turbulent. I mean the forces of the Line.”

“Oh.” She tried to look discreetly around Dr. Ekstein’s mass for sight of Agatha. “Well, isn’t that for the best? Isn’t the Line on the side of science and order?”

Dr. Naumann raised an eyebrow, which Liv found irritating. “Is that right? Consider Logtown, which they burned to the ground because it harbored Agents of the Gun; consider the conquest of Mason, where…” He rattled off a long list of battles and massacres.

Dr. Alverhuysen looked at him in surprise. “You know a lot about the subject.”

He shrugged. “I take an interest in their affairs. A professional interest, you might say.”

“I’m afraid I don’t follow their politics closely, Dr. Naumann.”

“You will. You will.” He leaned in close and whispered to her: “They’ll follow you, Liv.”

She whispered back, “Perhaps you should travel that way yourself, Philip.”

“Absolutely under no circumstances whatsoever.”

He straightened again, and consulted his watch. “I shall be late for my afternoon Session!” He left his glass on a bookshelf and exited by the south stairs.

“Unhealthy,” Ekstein said. “Unhealthy interests.” He glanced down at Liv. “Unhealthy.”

“Excuse me, Dr. Ekstein.”

She stepped around him, exchanged a polite good luck, good luck to you too with a grey-haired woman whose name she forgot, passed through a cool breeze and shaft of dusty afternoon sunlight that entered through the oriel window, heard and for nearly the last time was delighted by the sound of the peacocks crying out on the lawns, and deftly linked arms with Agatha and rescued her from Professor Dahlstrom’s droning. Unfortunately Agatha turned out to be a little too drunk and a little too maudlin, and did not share any of Liv’s nervous excitement. She blinked back tears and held Liv’s hand very tightly and damply and said “Liv—oh, Liv. You must promise you’ll come back.”

Liv waved a hand vaguely. “Oh, I’m sure I will, Agatha.”

“You must come back soon.”

In fact, she hadn’t given a moment’s thought to when she might return, and the demand rather annoyed her. She said, “I shall write, of course.”

To Liv’s relief then Dr. Ekstein tapped on a glass for silence, and quickly got it, because everyone was by now quite keen to return to their interrupted afternoon’s work. He gave a short speech, which did not once mention where Liv was going or why, and rather made it sound as if she were retiring due to advanced senility. Finally he presented her with a gift from the Faculty: a golden pocketwatch, heavy and overly-ornate, etched with sentimental scenes of Koningswald’s mountains and pine forests and gardens and narrow high-peaked houses. The occasion was complete, and the Faculty dispersed by various doors and into the stacks of the Library.

* * *

The Lodenstein Faculty stood on a bend in the river a few miles north of the little town of Lodenstein, which was one of the prettiest and wealthiest towns of Konigswald, which was itself one of the oldest and wealthiest and most stable and peaceful nations of the old and wealthy and stable and peaceful nations of the East.

Six months ago a letter had arrived at the Faculty from out of the furthest West. It was battered and worn, and stained with red dust, sweat and oil. It had been addressed to The Faculty—Konigswald—Of the Seven. Konigswald’s efficient postal service had directed it to Lodenstein without too much difficulty. “Of the Seven” was a strange affection, initially confusing, until Dr. Naumann remembered that four hundred years ago Konigswald had—in an uncharacteristic fit of adventurism—been one of the Council of Seven Nations which had jointly sent the first expeditions west, over the World’s Wall mountains, into then-virgin territory. Perhaps that fact still meant something to the westerners; Konigswald had largely forgotten it.

Strictly speaking the letter was addressed not to Liv, but to a Mr. Dr. Bernhardt Alverhuysen, which was the name of her late husband, who was recently deceased; but her husband had been a Doctor of Natural History and the letter sought the assistance of a Doctor of Abnormal Psychology, a title which more accurately described Liv herself. Therefore Liv had opened it.

Dear Dr. Alverhuysen,

I hope this letter finds you well. No doubt you are surprised to receive it. There is little commerce these days between the new world and the old. We do not know each other, and though I have heard great things of your Faculty, I am not familiar with your work; my own House is in a very remote part of the world, and it is hard to keep up with the latest science; and therefore I write to you.

I am the Director of the House Dolorous. The House was founded by my late father, and now it has fallen into my care. We can be found on the very furthest western edge of the world, nestled in the rocky bosom of the Flint Hills, north-west of a town called Greenbank, of which you no doubt have not heard. West of us the world is not yet Made, and on clear days the views from our highest windows over unCreation are unsettled and quite extraordinary.

Are you an adventurous man, Dr. Alverhuysen?

We are a hospital for those who have been wounded in our world’s Great War. We take those who have been wounded in body, and we take those who have been wounded in mind. We do not discriminate. We are in neutral territory, and we ourselves are scrupulously neutral. The Line does not reach out to the Flint Hills, and the agents of its wicked Adversary are not welcome among us. We take all who suffer, and we try to give them peace.

We have able field-doctors and sawbones in residence, and we know how to treat burns and bullet-wounds and lungs torn by poison gas. But the mind is something of a mystery to us. We are ignorant of the latest science. There are mad people in our care, and there is so little we can do for them.

Will you help us, Dr. Alverhuysen? Will you bring the benefit of your learning to our House? I understand that it is a long journey, rarely undertaken; but if you are not moved by the plight of our patients, then consider that we have all manner of mad folk here, wounded in ways that you will not find in the peaceful North—not least those who have been maddened by the terrible mind-shattering noise-bombs of the Line—and that your own studies may prosper in a House that provides such ample subject matter. If that does not move you, consider that our House is generously endowed. I enclose a promissory note that will cover your travel by coach and by riverboat and by Engine of the Line; I enclose a map, and letters of introduction to all necessary guides and coachmen on this side of the World; and finally I enclose my very best wishes,

Yours In Brotherhood,

Director Howell, the House Dolorous.

She had shown the letter to her colleagues. They treated it as a joke. Out of little more than a spirit of perversity she wrote back requesting further information. All winter she busied herself with teaching, with her studies, with the care of her own subjects. She received no reply; she didn’t expect to. On the first day of spring, rather to her own surprise, she wrote again, to announce that she had made her decision and that she would be traveling west at the first opportunity.

* * *

Now she couldn’t sleep. The golden watch ticked noisily at her bedside and she couldn’t sleep, and her head was full of thoughts of distance and speed. She’d never seen one of the Engines of the Line and could not picture what they looked like; but last year she had seen, in one of the galleries in town, an exhibition of paintings of the West’s immense vistas, its wide-open plains like skies or seas. Perhaps it had been two years ago—Bernhardt had been alive. The paintings had been huge, wall-to-wall, mountains and rivers and tremendous skies, some blue and unclouded and others tempestuous. Forests and valleys. The panorama: that was what they painted in the west. Geography run wild and mad. There’d been several with bloody battles going on at the bottom of the frame: FALL OF THE RED REPUBLIC, or something like that, was especially horrible, with its storm-clouds of doom clenched in the sky like sick hearts seizing; thousands of tiny men struggling in a black valley, battle-standards falling in the mud. They always seemed to be fighting about something, out in the west. There’d been half-a-dozen depicting nature bisected by the Line; high arched rail-bridges taming the mountains or rail-roads shaving the forests away; the black paint-blots that were the Engines seeming to move, to drag the eye across the canvas. There were even a few visions of the very furthest west, where the world was still entirely uncreated, and full of wild lights and lightning storms and land that surged like sea and strange beautiful demonic forms being born in the murk. . . Liv remembered how Agatha had shuddered and held herself tight. She remembered, too, how Bernhardt had held her arm in his heavy tweed-clad arm, and droned about Faculty politics, and so she had not quite lost herself in the paintings’ wild depths.

Now those scenes rushed through her mind, blurred with speed and distance. The House was a world away. She could not picture traveling by Line but she imagined herself leaving town by coach, and the wheels clattering into sudden unstoppable motion, and the horses rearing, and the coach lurching so that all her settled life spilled out behind her in a cascade of papers and old clothes and. . .

It was not an unpleasant sensation, she decided; it was as much exhilaration as terror. Nevertheless she needed to sleep, and so she took two serpent-green drops of her nerve-tonic in a glass of water. As always, it numbed her very pleasantly.

* * *

Liv settled her affairs. Her rooms were the property of the Faculty—she ensured that they would be made available to poor students during her absence. She consulted a lawyer regarding her investments. She dined almost nightly with Agatha and her family. She cancelled her subscriptions to the scholarly periodicals. The golden watch presented an unexpected problem, as her clothes had no pockets suitable for such a heavy ugly thing, yet she was not sufficiently unsentimental to leave it behind; eventually she decided to have a chain made and wear it around her neck, where it beat against her heart.

She visited her subjects and made arrangements for their future. The Andresen girl she transferred into Dr. Ekstein’s care; the girl’s pale and fainting neurasthenic despair might, she hoped, respond well to Ekstein’s gruff cheerfulness. The Fussel boy she bequeathed to Dr. Naumann, who might find his frequent sexual rages interesting. With a satisfying stroke of her pen she split the von Meer twins—who suffered from cobwebbed and gothic nightmares—sending one girl to Dr. Ekstein and the other to Dr. Lenkman. An excellent idea, as they only encouraged each other’s hysteria. She wondered why she hadn’t done it years ago! The Countess Romsdal had nothing at all wrong with her, in Liv’s opinion, other than being too rich and too idle and too self-obsessed; so she though Dr. Seidel might as well humor her. She gave Wilhelm and the near-catatonic Olanden boy to Dr. Bergman. She sent sweet little Bernarda, who was scared of candles and shadows and windows and her husband, to a rest cure in the mountains. As for Maggfrid. . .

Maggfrid came crashing into her office, late in the afternoon. He never understood to knock; the shock made her spill ink on her writing-desk. He was in tears. “Doctor—you’re leaving?”

She put down her pen and sighed. “Maggfrid, I told you I was leaving last week. And the week before that.”

“They told me you were leaving.”

“I told you I was leaving. Don’t you remember?”

He stood there dumbly for a moment, then hurried over and began to mop at her desk with his sleeve. She put her hand on his arm to stop him.

He was nearly a giant. His huge hands were scarred from a multitude of small accidents—he didn’t have the sense to look after himself properly. Someone who didn’t know him might have found him terrifying—in fact he was gentle and as loyal as a dog. Maggfrid was her first subject, and, in a manner of speaking, her oldest friend.

Maggfrid’s condition was congenital. His own blood had betrayed him. Sterile, he was the last of a line of imbeciles. Liv had found him sweeping the stone floors of the Institute of healing in Tuborrhen, where she herself had spent some years in a high white-walled room, in a fragile state, after the death of her mother. He’d been kind to her then. Later, when she was stronger, he’d been happy to be her test-subject; he was always simple and eager to please. He would answer questions for hours with his brow furrowed with effort. He bore even the more intrusive physical examinations without complaint. There were three ugly scars across his bald head, and a burn from a faulty electro-plate, but he didn’t mind. She couldn’t heal him—she had quickly realized he was beyond mending—but he’d provided subject-matter for a number of successful monographs, and in return she’d found him work sweeping the floors of August Hall.

“Doctor. . .”

“You’ll be fine, Maggfrid. You hardly need me any more.”

He began mopping up the ink again. “Maggfrid, no. . .”

She couldn’t stop him. She watched him work. He scrubbed with intense determination. It occurred to her that she could get up, walk away, lock the office behind her and he might remain standing there implacably scrubbing in the darkness. It was a painful thought.

Besides, she might need a bodyguard; she would need someone to carry her bags. It was even possible that fresh air, adventure, new scenery would do him good. It was certainly what she needed.

She put a hand on his arm again. “Maggfrid: have you ever wanted to travel?”

It took nearly a minute for his big pale face to break into a grin; and then he lifted her from behind her desk and spun her like a child, until the room was a blur and she laughed and told him to let her down.

* * *

She spent her very last day at the Faculty on the banks of the river. She sat next to Agatha on an outstretched blanket. They fed the swans and discussed the shapes of clouds. Their conversation was a little forced, and Liv wasn’t at all sorry when it drifted away, and for a while they sat in silence.

“You’ll have to a buy a gun,” Agatha said, quite suddenly.

Liv turned to her, rather shocked, to see that Agatha was smiling mischeviously.

“You’ll have to buy a gun, and learn to ride a horse.”

Liv smiled. “I shall come back quite battle-scarred.”

“With terrible stories.”

“I shall never speak of them.”

“Except when drunk, when you’ll tell us all stories of the time you fought off a dozen wild hillfolk bandits.”

“Two dozen! Why not?”

“No student will ever dare defy you again.”

“I shall walk with a limp, like an old soldier.”

“You will—” Agatha fell silent.

She reached into her bag, and took out a small red pocket-sized pamphlet, which she handed solemnly to Liv.

According to its front cover, it was A Child’s History of the West.

Its pages were yellow and crumbling. Its frontispiece was a black-and-white etching of a severe-looking gentleman, in military uniform, with dark features, a neat white beard, a nose that could chop wood, and eyes that were somehow at once fierce and sad. He was apparently General Orhan Enver, First Soldier of the Red Valley Republic, and the author of the Child’s History. Liv had never heard of him.

“I’m afraid it’s the only book I could find that says anything about where you’re going at all,” Agatha said.

“This is from the Library.”

Agatha shrugged. “Steal it.”

“Agatha!”

“Really, Liv, it’s hardly the time for you to worry about that sort of thing. Take it! It may be useful. Anyway, we can’t send you off with nothing but that horribly ugly watch.”

Agatha stood. “Be safe,” she said.

“I will.”

Agatha turned quickly and walked off.

* * *

Grunting, Maggfrid heaved up Liv’s heavy cases onto the back of the coach. The horses snorted in the cold morning air and stamped the gravel of August Hall’s yard. The Faculty was still abed—apart from the coach and the horses and a few curious peacocks the grounds were empty. Liv and Agatha embraced as the coachman stood by smoking. Liv hardly noticed herself boarding the vehicle—she had taken four drops of her nerve tonic to ensure that fear would not sway her resolve, and she was therefore somewhat distant and numb.

The coachman cracked the whip and the horses were away. The die was cast. Liv’s heart pounded. Balanced on her lap were the Child’s History of the West, the ugly golden watch, and a copy of the most recent edition of the Royal Maessen Journal of Psychology. She found all three of them rather comforting. Maggfrid sat beside her with a frozen smile on his face. Gravel crunched, the lindens went rushing past, the Faculty’s tall iron gates loomed like a mountain. Agatha gathered up her skirts and ran a little way after the coach, and Liv waved and in doing so managed to drop her copy of the Journal, which fluttered away behind her down the path. The coachman offered to stop but she told him keep going, keep going!

CHAPTER TWO:

A GENTLEMAN OF LEISURE

Riverboat, due south from Humboldt, through night and red rushes, through neutral territories. Long-legged herons stalked the banks. The riverboat came as a roaring invader into their silent muddy world: its vast dark weight and the golden light and swirling thumping piano music pouring from its windows sent the birds bursting into panicked flight like shots had been fired. . .

But it was only a gambling boat, a private enterprise chartered out of the free Baronies of the Delta, three decks of music and drinking and whores and conmen and business travelers and suckers. It carried no cannon. Its great paddlewheel clattered and splashed. (The Folk who turned it were discreetly locked away below). It was painted scarlet and blue, rimmed with brass, flying a variety of flags; it was quite pretty in the torchlight. A young man in pinstripes vomited over the side while his girlfriend picked his pocket. Six blond and prosperous farmers staggered out of the bar arm-in-arm singing a song about fighting. The floor of the bar was bright with spilt whiskey and broken glass, and the pitch and yaw of the boat sent a constant whirl of men and women around and around in drunken circles about the roulette wheel and the dice-tables and the knots of men clutching tightly to their cards and their fragile little heaps of coins and worn sweaty banknotes.

Everyone was talking much too loudly about sex, about business, about crime, about war; and about plans for when the War was over, which always got a laugh. A man with a quick mind and sharp hearing could have picked up valuable intelligence — and Creedmoor had a passably quick mind and the ears of a fox. But he was retired, and happily so, and so he shut his ears and let the babble wash over him. He liked to be among people; he liked the noises and smells of crowds. This wasn’t peace. There was no peace and there never would be. But it was close enough for the time being.

He sat in a half-dark corner playing cards with strangers. His back was to the wall, just in case.

The table was playing the Old Game, with the suits they used in the towns of the Delta Baronies—rifles, shovels, wolves and bones. A game of bluff and cunning; Creedmoor excelled at it. There was a rich-looking man in a green necktie and glasses, a less rich-looking man in a brown suit with a bald head, and a stupid-looking young man called Buffo who’d joined the boat that morning from a one-street town called Lezard, with bloodstains on his boots and a burlap sack full of clinking gold coins. No questions asked. Buffo balanced a black-haired green-eyed girl on his lap, who seemed to like it when Creedmoor smiled at her. Everyone was substantially less rich than they’d been at the start of the evening, except for Creedmoor, and the girl, who appeared to be a neutral party.

Creedmoor had joined the boat two days ago in a town called Humboldt, where some old enemies had spotted him. He’d been sitting on a painted bench on Humboldt’s waterfront, watching the young women go by in their blue and green summer dresses, when his peace had been shattered by the sound of engines and the smell of smoke. Even before he saw it he sensed the black staff car coming down the dirt road behind him. Linesmen. He jumped up, walked quickly but calmly down the pier, and bought a ticket for the first boat out. In the old days he might have stayed and fought, but he was tired of fighting. Anyway, he was only passing through Humboldt on a detour to avoid the Shrike Hills, which when he’d last been that way thirty years ago had been full of drowsy little villages. Now to his great annoyance the Hills were being flattened and built over by the Line—farms replaced by factories, forests stripped, hills mined and quarried to feed the insatiable holy hunger of the Engines.

He was happy enough on the boat. He hadn’t been traveling anywhere in particular anyway. It was six years since he’d last heard the Call. It was impossible to avoid his masters or escape them, but he did his best to make himself appear both idle and useless to them—a burnt-out case. It appeared to be working well enough. He regarded himself, provisionally, as a free man—which considering his line of work was no small accomplishment.

More money changed hands. The rich-looking gentleman in the necktie gave a sad laugh and tossed his last crumpled bills in the air. Creedmoor deftly snatched them.

“You’re a devil, sir.”

“Not tonight,” Creedmoor said, and smiled.

Creedmoor’s hair was a little thin, brown turning grey; his face was red and lined and rough. He looked like he came from Lundroy peasant stock, which he did. If you saw him smile, you might think he was still a young man; if you saw him sometimes when he thought he was alone he might look a hundred years old. The three men who sat across the card-table from him behind rapidly-diminishing piles of money had seen a simple old man when they first sat down to play. Now, Creedmoor judged, at least two of them were considering drawing a weapon on him. He hoped they wouldn’t be so foolish.

Creedmoor’s hoard of bills and coins grew, big and glittering and beautiful. The rich-looking gentleman staggered drunkenly off, cursing in disgust. The black-haired green-eyed girl moved herself pointedly from Buffo’s lap to Creedmoor’s.

Buffo sneered in disgust and spat on the floor.

“I’ll ask you not to do that,” Creedmoor said. “Lowers the tone.”

Buffo’s bloodshot eyes narrowed and his leg started to twitch. He appeared not to have slept in days. He stared at his cards and muttered old fool and whore, the latter presumably addressed to the girl. He repeated it: whore, whore, whore. The girl laughed, high and cheerful. Creedmoor liked her. She had an unfortunate black wen on her lip but was otherwise lovely, and Creedmoor put his arm around her and was happy.

* * *

When he woke the next morning in his narrow cabin his head hurt so dreadfully that for a moment he thought his old masters were Calling to him. That was how they announced their presence; with pain, and noise, and the smell of blood and fire. He began to plead and make excuses. He was answered with silence, and it quickly became clear that he was experiencing nothing more extraordinary than a hangover.

The boat lurched. The girl was squeezed into his bunk and her arm with its fine dark hairs was draped across his own scarred chest. Her green eyes looked at him curiously. He hoped he hadn’t spoken out loud.

* * *

He passed the day in a deck chair, with a sentimental romantic novel. He pulled his hat down over his eyes and warmed in the sun like an elderly alligator. The river shone white behind and blue ahead, and the broad plains were baked brown, and encircled in the distance by dark pines and blue mountains. A few farms; no towns. No Line—not yet. The plains were a hazy emptiness, uninhabited land, a vast and vague beauty, not yet shaped or Made by anyone’s dreams or nightmares.

He ate no lunch. Sometimes he forgot.

A shadow fell over him, and woke him. It was the girl, blocking the orange haze of the late afternoon sun. She looked pale and nervous, and Creedmoor quite forgot what he’d liked about her. He also forgot her name.

“John,” she said, “I’ve been thinking. . .”

John was his real name. He didn’t recall giving it to her, though admittedly he’d been drinking lately. He sure didn’t see how it was any business of hers to be using it. His face set into a scowl.

“This boat stops in Aral,” she said. “And from there it’s not too far to Keaton, or Jasper. And there’s work on the stage there, and everyone says I’m pretty enough. And I know you got money. And I know you’re smart, smarter than any of these boys here, and I don’t know what you do for a living but I know it ain’t regular, and what I mean is if you wanted to travel together. . .”

“I’m not going to Keaton. Or Jasper.”

“Wherever, then. I’m sick of working this boat, John. I want to see the world.”

“The world’s a bloody awful place,” he said. “This boat is as good as it gets.” And he pulled his hat down again, so he wouldn’t have to see the hurt look in her eyes.

Once she’d stormed off he went back to his novel. He saw a happy ending coming, but he didn’t believe in it.

He dozed in his deck chair. He woke again in the evening, disturbed by the distant whine of ornithopters. Every one of his old muscles tensed, and a sour taste of fear snuck into his mouth. He lifted his hat just enough to examine the red evening sky; otherwise he was still. After a few moments he saw them, miles off, six black specks moving in formation high over the plains. Advance scouts for the Line. They bled black smoke behind them; they scored black lines across the sky. The whine became a drone became a clattering whir of iron wings as they passed overhead, and Creedmoor quietly pulled his hat down over his face. The drone faded again and he untensed.

He ate alone in his room, worrying boiled meat from the bone with his teeth.

* * *

In the bar that night Buffo held forth. The young man had slicked back his hair and pressed his suit and cleaned the blood from his boots, and looked quite handsome. He leaned on the bar and shouted over the noise of the river. The black-haired girl was back with him. He was throwing money around and telling stories of how he’d won it—as he drank and swayed his story shifted, so that first he’d been a famous gambler and then he’d made his fortune running rifles to the besieged towns of Elmo Flats past the blockades of the Line, and then he’d robbed a bank in Jasper, and then he’d invented a wonderful new headache-cure, but been cheated out of the patent by a cunning little Northerner.

If Creedmoor was any judge every word of it was a lie, but Buffo’s audience only grew throughout the evening. Creedmoor drank alone. Sometimes Buffo caught Creedmoor’s skeptical eye and scowled, and Creedmoor smiled, and Buffo bared his teeth and lost the thread of his latest story. The girl seemed angry with Creedmoor too. Those ‘thopters had quite soured his mood.

* * ** * ** * *

Buffo began a new story.

“. . .and that was where . . . that summer . . . after the, you know, after I was saying how I robbed that bank in Keaton, I mean Jasper, and . . . can I trust you all? Come closer, can I trust you to keep a secret? I fucking well ought to be able to, all the drinks I bought you . . . that was where I got this.”

The boy fumbled drunkenly in his jacket. He pulled out a small and cheaply-made revolver, snagged it on his tie, and dropped it on the floor. He recovered it and then slammed it down on the table.

He said, “Yeah.” People drew nervously away from him.

“That is what you think it is,” he said, loosening his tie.

“Let me tell you. Let me tell you. They don’t recruit just anyone. Only the bravest and wildest are chosen by the Gun to be its Agents. They’d had their eye on me for months, I reckon—maybe since I did that bank in, in Shropmark, maybe since I broke out of the gaol in White Plains, maybe since the shooting in . . . but that’s another story. Don’t touch that weapon. Don’t none of you even fucking look it. There’s a demon in that weapon. A god lives in it. There’s a demon in me. That was—I was in a bar in, in that town, just by myself, just quiet, because you see what you people don’t know is that when you rob a bank, see, you have to stay quiet, you can’t go spending your money, you have to be even more quiet and innocent than if you were actually innocent, if you’re smart. And so a man came to me in the dark, and he was dressed all in black and he had a black hat and he had red eyes, and they say that’s how you can tell, because they’re not like ordinary men any more. We’re not like ordinary men any more. He sat down beside me and he said, I’ve got a proposition for you. What would you say, what would you say if they asked you? I mean, they wouldn’t ask any of you—they only take dangerous men. They only take wicked men. They only take the worst of the worst and the best of the worst. Robbers and murderers and anarchists. I’ve been—I’ve known all of them, Abban the Lion, Blood-And-Thunder Boch, Dandy Fanshawe, Black Casca, Red Molly—I’ve had her—all the legends. All the stories. What would you say, if they asked? All that power. You’d live forever, or at least you’d never be forgotten after you’re gone. But the War. . . I mean the Line covers half the world. And it’s always growing. And it has Engines, and ‘thopters, and bombs, and a million fucking men. And all Gun has is—is us. Heroes. Is it worth it? They can’t win. They can’t win. The Line’s going to get them all in the end. That’s—that’s what I’m doing here, see, I have a mission. A mission for the Gun, against the Line. I’m part of it. The Great War. I’d say it’s worth it. I’d say. I’d say yes if they—”

Buffo’s eyes were darting all around the bar. His audience were uncertain, drawing slowly away from him. The black-haired girl had busied herself elsewhere. He didn’t seem to notice.

“Fuck yes it’s worth it.” He banged his weapon again on the table. He stood suddenly, swaying, and tore open his shirt to bare a wiry chest. “You can’t kill me. They made me strong. I’m not like you any more. Shoot me. Shoot me or stab me if you dare.”

No one took him up on his offer. He didn’t say anything else. After a while he wandered out into the night, snatching up his money but leaving the cheap revolver forgotten on the table. Creedmoor followed.

* * *

Creedmoor waited until Buffo had finished pissing over the side before he spoke.

“That’s a dangerous story to be telling.”

The young man turned, and stumbled drunkenly against the rail. His face was in darkness but shafts of light from the windows criss-crossed his hands and body. The riverboat’s great paddle-wheel turned and turned in the darkness behind him, and the night sky above was full of gunmetal-grey clouds.

“We’re a long way from any Stations of the Line out here,” Creedmoor said, taking a step closer. “And you’d know if any of the Line’s men were aboard, because they stink, and they’re stunted, and pale, and you can always spot ‘em. They grow all packed in together in their big cities and the smell of oil and coal-smoke never leaves ‘em. And they never go anywhere without their machines, and their vehicles, and their Engines. But even so. Even so. Rumors fly faster than birds and faster even than Engines.”

With the assistance of the rail, Buffo stood straight. “I’m not scared of Linesmen.”

Creedmoor paused, and shook his head. “The Agents of the Gun, now, I hear you can’t tell them apart from ordinary men. Or even women. Except that every one of them carries the weapon that houses the demon that rides them and barks at them and makes them strong. Yes? But how would you know—because who doesn’t carry a weapon these days, and aren’t all weapons a little monstrous in their way? Fortunately the Gun’s Agents are few and far between, because you’re right—the Gun takes only the worst and wickedest. But if there were Agents aboard, they might not like your stories.”

Buffo shrugged.

“And these are neutral territories we’re passing through now, and these people are businessmen and farmers going to market, and they may be playing at being wicked people for a night while they’re away from their wives, but they do not love Agents of the Gun. The Great War will come to them eventually, they cannot stay neutral forever, Line is too greedy and Gun too ruthless; but for now they are neutral and happy that way. They may slit your throat in the night.”

“I don’t care what they think.” Buffo waved dismissively, and nearly fell over.

“They don’t care for bank-robbers either, come to that. Not after the story’s over. How did you come by that money, really? Who did you kill for it? I’m curious.”

Buffo spat at Creedmoor’s feet.

“Fair enough.” Creedmoor spoke quieter as he came closer to where Buffo swayed. “And if there were a man aboard who’d retired from the Great War, he might not want you telling stories either. You might bring down unwanted attention. You might disturb his peace. You might bring back bad memories; you might with your lies tarnish glorious memories. A man like that might politely ask you to shut up, and get off at the next town, while you still have your money and your neck. What do you say?”

Buffo wasn’t listening. He shoved Creedmoor’s shoulder and said, “Leave me alone, old man.” So Creedmoor, sighing, slapped Buffo’s hand aside, and lifted him struggling by the collar of his shirt, and reached down into those depths of his spirit where that savage inhuman strength lay, and hurled Buffo over the edge, out into the night, arcing high into the air and far past the white water rushing through the boat’s wheel. The boy’s arms and legs pinwheeled in the air and coins rained from his pockets. He splashed down sixty feet behind the boat in a slow dark bend of the river.

Creedmoor looked around; no one seemed to have noticed the brief struggle or heard the distant splash. Buffo’s tiny figure trod water, waving his arms and shouting, but the music drowned out his voice and the boat left him behind.

Creedmoor noticed that the boy had dropped a fistful of notes on the deck. His back ached a little as he stooped to gather them up.

The green-eyed girl waited on Creedmoor’s table that night. She kept looking around anxiously, as if wondering where her stupid young man had gone. Creedmoor tipped her well.

* * *

He woke at noon, lurching bolt upright in his bed. Pain stabbed at his head and he staggered to the window, where a red-hot sun burned and the smell of the river was stagnant and made him sick. The pain—the smell of blood and cordite in his nostrils—there was no mistake this time. He’d forgotten—he’d forgotten how it hurt, when they Called. For six years he’d been idle and alone in his soul. He’d locked away those memories, his wounds had healed. Now he felt his Master kicking down the doors and Calling for him. The world moved very slowly around him—outside the window the paddle-wheel turned as slowly as the long centuries of the Great War—and a fly crawled with infinite patience across his knuckles. He’d gone to sleep in his clothes and his tie was suddenly choking him. The weapon—the Gun—the temple of metal and wood and deadly powder that housed his Master’s spirit—sat on the floor by the bed, and throbbed with darkness. All the room seemed to bend and sway around it. Creedmoor couldn’t face looking at it yet.

The voice sounded in his head, like metal scraping, like powder sparking, like steel chambers falling heavily into place.

– Creedmoor. You are needed again.

CHAPTER THREE

THE BLACK FILE

It was the morning of the first day of the third month of the year 1889 —or 296 in the reckoning of the Line—and Sub-Invigilator (Third) Lowry sat in a small ill-lit office, filling out forms. The tall moon-faced clock that loomed behind Lowry’s shoulder had just informed him, through a series of insistent whistles and clacks that still to this day induced anxiety, though Lowry was now thirty-two years old, and had been a soldier for twenty-two years, that the time was 11.45. He had not slept in two days. The bags under his eyes were like big black zeros and the stubble on his jaw was a palpable disgrace. Every hour on the hour he took one of the dark grey anti-sleep tablets, which were not to be confused with the light grey appetite-suppressant tablets, or the black intellect-sharpeners. He had work to complete.

His office had one small square window, too high to allow any view that might distract him; nothing was visible through it except slate-grey clouds. That view never changed. In the haze of industry that surrounded Angelus Station it was always grey. For all Lowry knew the sky beyond those smog-clouds might be blue or white or any other horrible thing, but down here it was dark.

His office echoed with the sound of machinery outside, his typing inside. Angelus Station was preparing for the return, refueling and re-arming of its Engine, which occurred every thirteen days, and was always a vast undertaking. No delays were tolerated. Every machine and process of the Station was being pushed to capacity. Lowry pecked away at the keys, slowly, one-fingered, taking infinite agonies over the composition of his reports, on which his career might depend.

Not only was his office small, but a tangle of pipes and cables poked through its walls at roughly head-height, carrying important fuels and cooling fluids from one part of the Station to another, clanging and steaming and occasionally dripping warm acrid water onto the back of Lowry’s neck. A person not familiar with the operations of the Line might infer, from Lowry’s surroundings, that he was low-ranking; that would be wrong. In fact Lowry occupied a position somewhere in the middle range of the upper reaches of the hierarchy of Angelus Station’s several hundred thousand personnel, military and civilian, a hierarchy which was almost as complex and convoluted as the Station’s plumbing. However, the Line believed in keeping its servants humble, the more so the more responsibility was entrusted to them. The Angelus Engine’s Sub-Invigilators (Second) and (First) had even smaller offices than Lowry’s. The Invigilator had no office, as far as Lowry knew, and possibly did not exist except in the form of a signature on certain official documents. The higher ranks and civilian administrators were a mystery to Lowry, one which it was not his business to investigate.

Three identical black-and-grey uniforms hung from the pipes behind Lowry’s back. They made him feel like unfriendly eyes were spying on him, which he put down to sleep-deprivation—he wasn’t imaginative, normally.

His office had one single decoration: a copy of the commendation that had been issued to his unit of the Angelus Engine’s Second Army for its part in the capture and execution of the Agents Liam “The Wolf of the South” Sinclair and Goodwife Sal. It was sixteen years old.

On a shelf over his desk he had a copy of the Black File. It was his most treasured possession. It occupied twelve thick black binders, and every one of its pages contained top-secret intelligence on the Line’s great enemies, the Agents of the Gun. It was not widely circulated. Lowry had undergone a six-month review process before being permitted to read the thing, and another two-year review to be permitted to possess a copy.

He had made a special study of the subject of the Agents, and believed himself to be something of an expert. His hatred of them was unusual even by the standards of officers of the Line. No particular reason why. They just disgusted him, was all. He was a simple man.

The Wolf of the South and Goodwife Sal were both in the Black File, under DECEASED. Since their bodies had been burned it was, Lowry supposed, their final resting place. Six years ago he had been an advisor to an operation that had killed Blood-and-Ashes Morley, at the cost of only forty-six Linesmen, which had earned Lowry himself a footnote in the Black File. Now he was engaged in filing his report on the recent death of Strychnine Ann Auburn. It was an exquisitely tricky business. If all went well it would earn him a second footnote in the File; however, the slightest trace of vanity or ambition could earn him demotion, disgrace. The Line did not tolerate vanity or ambition in its servants.

* * *

SUMMARY

The first joint operation between the forces of the Angelus Engine and the forces of the Dryden Engine since the Razing of Logtown in Year 279 can be judged to have met with total success. Command structures were successfully integrated to ensure effective hierarchy and full obedience while leaving adequate operational independence to ensure prompt and effective action. Casualties were inconsequential. The Dryden Engine’s forces assaulted the enemy’s position and rightly claim a significant portion of the credit for the execution. However, intelligence provided by Sub-Invigilator (Third) Lowry of the Army of the Angelus Engine proved essential to the success of the operation

However, it is important to note that intelligence operations contributed significantly to the success of the operation. The efficient interchange of information is critical to the forward Progress of the Line, and though personal ambition is irrelevant to that Progress a full record must be made. Sub-Invigilator (Third) Lowry of the Army of the Angelus Engine designed the intelligence-gathering operations which

Sub-Invigilator (Third) Lowry of the Army of the Angelus Engine participated in the intelligence-gathering operations which

The Angelus Engine permitted its personnel to oversee the intelligence gathering operations which led to the tracking of the Agent, Ann Auburn, a.k.a Strychnine Ann, a.k.a. Strychnine Auburn, see H.22.7, R.251.13, to the town of Corbey, north-east of Gibson City, see L.124.21. Mathematical analysis of the patterns of her attacks located her in the vicinity of Corbey, and questioning of locals provided her precise location. Among numerous personnel whose duty it was to participate in those operations were Sub-Invigilator (Third) Lowry. . .

* * *

When he’d finally crafted his report, not to his satisfaction, exactly, but to a point where nothing further could be done to protect himself, he delivered it into the pneumatic tube at the far end of the hallway, thrusting it in the decisive way one might thrust a knife into someone’s gut. Then he staggered across the littered and crowded and smog-haunted Concourse to his dormitory building. It was cold out, so it was probably night. He took a fistful of sleeping pills and was immediately unconscious.

In his dreams he saw the Agent, Ann Auburn, once again. She’d been tall, much taller than Lowry, black-skinned, shaven-headed, gold-ringed, strikingly beautiful if you liked that kind of thing, which Lowry did not. A real arrogant bitch. She’d been hiding among sympathizers in Corbey Town, in a loft over a barn like a bloody goat or something, which had not diminished her arrogance, and had been striking at Line cargo transports along the river and roads. Dryden forces had encircled the town, launched poison-gas rockets, then closed in. Lowry had watched through a telescope from a safe distance as the cornered woman fought her way out snarling and laughing through fire and blood and the billowing blind-eye white haze of deadly gas, killing and killing until finally her wounds dragged her down, too numerous and too deep for her masters’ power to heal. . .

But in his dream he stepped through the ‘scope’s cross-hairs and was down in the killing ground, walking with the same strutting immunity as the Agent herself.

Stand down, lads. Let me show you how it’s done.

He seized by her long thin neck and slammed her against a wall. She moaned. He yanked at her hooped gold ear-rings, and she cried out.

See, lads? It’s simple. It’s all a question of authority.

He slapped her, made her nose bleed, made her beg wordlessly.

You just have to show them who’s in charge.

Lowry typically didn’t dream, not unless he’d miscalculated the dosage of his various standard-issue performance-enhancing chemicals, and so he experienced it all with shocking intensity and pleasure.

* * *

He woke in a guilty panic. He was alone in the room—the three other men with whom he shared his billet were awake, gone, packed. The room’s narrow window opened over the Primary Concourse and Lowry knew at once, from the sounds of the machines and crowds, that the Engine had returned. There was no shouting, no cursing, no talking at all; the Station’s personnel worked in near-silence, in respect or terror or awe. Lowry had been born and raised in the basement levels of Angelus and was as attuned to its crowd noises and machine noises as it was possible for any mere person to be.

And the thing itself waited on the Concourse below, its metal flanks steaming, cooling, emitting a low hum of awareness that made Lowry’s legs tremble. . .

Quick calculation: he’d slept for rather more than sixteen hours. He was due to report to the staff of the Engine some two or three hours ago.

He dressed, ran out into the corridor and threw himself in stumbling rag-doll terror down the dormitory’s concrete staircase, still fumbling on his spectacles, and stepped out onto the crowded wide-open Concourse, where he was obliged, under the eyes of Authority, to walk, never to run, and to show the proper indifference to his own individual fate.

Two great busy Halls with roofs of iron girders and dirty green glass processed the Engine’s passengers and crew. One Hall handled civilians and outsiders who’d purchased passage; one handled military personnel. Lowry reported to the latter. He waited, in agony, under the eye of disapproving clock-faces, in a queue that zig-zagged back and forth across the floor’s greasy tiles in much the same way that the Line ran across the continent. He presented his papers at the counter and said, “Sub-Invigilator (Third) Lowry, reporting.”

Behind the counter sat a woman with a tautly-wound bun of steel-gray hair, a long sharp nose, distant eyes. She studied a roll of typed paper and said, “No.”

“What?”

“No.”

“I said Lowry, woman, I have orders to go east with the Engine to Archway. See here?” He pointed at his papers.

“See here?” The woman pointed at her papers, under I for Invigilator (Sub) (Third), where his name significantly did not appear. Her finger was stub-nailed and abominably stained with black ink.

“There must be some mistake.”

That was impossible, of course—the Line made no mistakes. He said, “I mean, I must have made some mistake,” in case anyone important was listening.

She shrugged, and bent down over her paperwork. Lowry saw that she kept three steel pens shoved into the back of her hair, one of which was leaking; they looked like loose wiring, or vents for internal machinery.

He pressed his face up against the grille in the glass and whispered, Please.

She looked up at him with blank contempt, sighed, and waited for him to go away; which, after what felt like hours, he did.

He pushed through the crowd, which parted nervously around him. Part of his mind was trying to calculate causes—had he been removed from service for his tardiness? Had the Auburn Report, despite his best efforts, contained unacceptable traces of pride? Had he spoken blasphemy in his sleep? Had he contradicted, without remembering it, some superior officer, had he. . .? Part of his mind was trying to calculate consequences: should he fear only for his career, or also for his life? Most of his mind was blank.

“Sir?”

He didn’t hear it at first.

“Sir?”

The gray-haired woman was calling him. He slumped back to the counter, numbly expecting further humiliation.

“Sir.” She sounded suddenly anxious, apologetic, and that made him stand up a little straighter. He leaned forward and snapped, “What?”

She handed him a short telegram. “Sir, I apologize, I. . .”

“Shut up,” he said.

He read the telegram. It didn’t take long, and it left him entirely confused.

“Kingstown,” he said. Far to the west—indeed, the Line’s westernmost point. At least two weeks away. The Angelus Engine was going east, which meant that he would have to wait for the Archway Engine to pass through, which would take him only as far as Harrow Cross, from where perhaps the Harrow Cross Engine would take him west to. . .

“My apologies, sir,” the woman said. “In all the rush, sir, I forgot—”

He smiled at her, baring bleached teeth. “What’s your name, woman?”

* * *

The telegram said:

FOR SUB-INVIGILATOR (THIRD) LOWRY OF THE ARMY OF THE ANGELUS ENGINE:

KINGSTOWN STATION

SETTING ASIDE ALL OTHER BUSINESS

WITHOUT DELAY

It was unsigned.

Copyright © 2010 by Felix Gilman