Dale Sampson is used to being a nonperson at his small-town Midwestern high school, picking up the scraps of his charismatic lothario of a best friend, Mack. He comforts himself with the certainty that his stellar academic record and brains will bring him the adulation that has evaded him in high school. But his life takes a bizarre turn as he discovers an inexplicable power: He can regenerate his organs and limbs.

When a chance encounter brings him face to face with a girl from his past, he decides that he must use his gift to save her from a violent husband and dismal future. His quest takes him to the glitz and greed of Hollywood, and into the crosshairs of shadowy forces bent on using and abusing his gift. Can Dale use his power to redeem himself and those he loves, or will the one thing that finally makes him special be his demise?

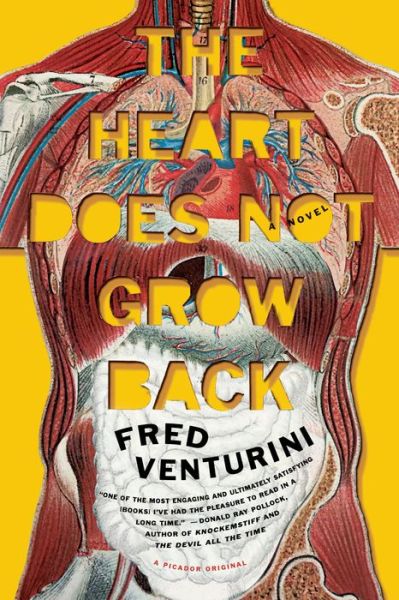

Fred Venturini’s darkly comic debut, The Heart Does Not Grow Back is available November 11th from Picador.

Tape and gauze smothered my partial ear. My hand was bandaged so completely it felt like a club. Even with the painkillers, I had trouble sleeping. A nurse checked the various electronics attached to me and woke me up. I saw Mom asleep on an easy chair pulled up beside my bed, her purse on her lap. It was two in the morning and I didn’t wake her. She looked terrible, tired, sick. Each day I noticed something different about her, but on that night, I noticed her breath, her ease of sleep. Perhaps it was just the emotional aftershock, but I finally knew how bad it was. My sobbing woke her up. She scrambled to my side, taking my healthy hand, sandwiching it in hers, crying along with me, kissing my cheek, our tears mixing on the palette of my flesh, the sterile, sour smell of tape and gauze blending with perfume that reminded me of cherries.

I squeezed her against me with my good limb.

“Mack?” I whispered.

“I saw him earlier. He’s going to be fine.”

“Fine for a normal person, or fine for him? How bad is he hurt?”

“He was shot in the shoulder,” she said. “They’re going to do some surgery, but his life is not in danger.”

“Which shoulder?”

“The right one.”

“Then his life is in danger,” I said.

She leaned over my bed, her legs wobbling and weak.

“Mom, sit. I’m doing fine.”

Sobs gobbled up her words. She put the back of her hand to her mouth, as if to excuse herself, then sat. “I’m sorry,” she muttered. “I’m just so happy you’re okay.” Then she lost it, doubling over into her hands, the rise and fall of her back betraying every crippling sob.

We cried together, apart, for different pieces of ourselves that were dead or dying. I finally asked. “Mom what’s wrong with you? Please just tell me.”

She sniffled, breathed, then shrugged. “I’m not sure.”

“Have you seen a doctor?”

“Yes. Oh yes, of course,” she said, lying. She smoothed my hair, smiled at me until I fell asleep again.

The next day, I was up and around, a deep itch burning under the gauze of my ear and hand. The doctor called it normal, the itch of healing, a good sign. My hand had been operated on to clean things up, screw some things together. Half my ear was gone, but my hearing was intact. This was worse than any “healing” itch I’d ever experienced. The flame of this itch was like poison ivy blossoming under the skin, an itch that destroys your regard for your own flesh, making you want to scratch so deep there’s nothing left but bone.

When Mack could take visitors, I headed up to see him. He had most of his right side wrapped in bandages. He was fresh out of surgery, his eyes shiny with drugs. We clamped our hands together and leaned into a clumsy hug.

“I’ll be robotic, man,” he said, nodding at his shoulder. “I’ll throw the ball a hundred miles an hour now.”

They had saved his arm, but he would need more reconstruction. The bullet had destroyed most of the shoulder joint, which could be patched together, but the tendons, bones, cartilage, and all the other intricacies of the joint could not be recaptured. Not the way they used to be, anyway. His arm could be saved for things like shoveling a fork into his mouth, but he’d be opening jars and doors left-handed. He would never raise his right arm over his head without grimacing. He would never throw again.

Days after returning home, the itch in my hand was alarmingly bad, so I took the bandage off and checked it myself. The doctor warned me of infection, demanding that I keep the bandages on for a full five days, after which they were going to evaluate me for another surgery, perhaps taking my whole hand away for a prosthetic, since movement in my remaining pinky and thumb was nonexistent.

I took the bandage off to reveal an entire hand, all flesh, all bone, all my fingers present, grown back to their full shape. I had heard of phantom-limb syndrome, how people can sometimes feel and move limbs that aren’t there anymore, but all they needed to do was look at their stump to know the truth. Unless I was experiencing a drug-fueled hallucination, my hand had completely regenerated.

I sat on the couch and stared at the wall for a long time, trying to catch my breath. I closed my eyes, wondering if my hand would still be there when I opened them. It was still there, still complete. Even my fingernails were back. I balled a fist with no pain, I flipped off the wall, I flicked my fingers. I touched them with my other hand to assure myself they were real. I popped my knuckles and I searched every inch of flesh—looking closely, under the light, I could see a faint, white border where the new fingers had grown back, a dividing line between my original flesh and the new, regrown fingers. It wasn’t a thick line of scar tissue, just a slight difference that I could barely detect.

I used my new hand to yank the bandage off my ear—the ear had also returned, though it was still a bit pink.

“Mom,” I said, trying to say it loudly, but only a whisper came out. “Mom,” I repeated, getting her attention.

“Coming,” she said. She was lying down, something she did all the time now. We never said the C word. I kept insisting that she go to the doctor, and the subject inevitably got changed. I tried aggression. I tried to question her love for me, telling her if she didn’t have the simple will to live, she was betraying her only son.

“I do want to live,” she said. “Sometimes trying your hardest to stay alive isn’t living at all.”

She shuffled into the room, thin and gaunt. I held my hand up. She smiled. I couldn’t believe the look on her face, the complete opposite of my own astonishment. I thought we’d go to the doctor and get an explanation. Was anyone else out there like this, or was this affliction completely unique?

She took my hand. After a thorough inspection, she brought it up to her papery lips and kissed it. “This is God making up for what was taken,” she said. “This is God making things right.”

She died in the middle of my senior year. I didn’t need much in the way of credits to earn my graduation, and we both agreed I couldn’t go back. Still, she begged me to walk the stage and take my diploma, if she lived that long. “There’s ways to hide your hand,” she said. “We’ll think of something by the time May rolls around.”

So I stayed home, and despite her weakness, she went to school a few times a week to bring back classwork from fully understanding teachers so I could knock out the last of my requirements. We wanted to keep my secret until we understood what was happening to me.

She wanted to die at home, but I insisted on driving her to the hospital when the pain got bad enough. I was the only one at her side when she passed. Since Dad left, we were always a family of two, and any attempt to discuss extended family ended with her shaking her head and saying nothing.

Just before she took her last breath, she squeezed that same reborn hand, barely able to speak, her body drenched with tubes and masks and lights and cancer. Cancer was everywhere, in her bones, in her breasts, in her liver, in her lungs. I never pulled any plugs on her. I hoped that God would make up for what was taken, that He would make things right. But He didn’t, and she died in front of me, leaving another empty seat for my graduation.

After she died, I lived alone. I didn’t turn eighteen for a few more months, so I had to be careful. The utility bills kept coming in her name, and I kept paying them. No point changing the name since I wasn’t officially old enough to enter a contract. As long as the heat and lights stayed on, no problem. The house was paid for. I didn’t care that I wasn’t on the title. She had no life insurance and since the bank was local, it was easy enough to empty her checking account with a forged check.

Despite her wishes, I couldn’t bring myself to leave the house on graduation night, so I called Principal Turnbull and asked him to mail my diploma. Mack did the same. “I don’t need to walk across some stupid fuckin’ stage to get where I’m going,” he told me. He called, but rarely, and when he did, we didn’t tread any tragic ground. Nothing about my mother’s death, nothing about the shooting or our injuries. He came to her tiny funeral and hugged me but we barely talked. Now, only phone calls and just small talk, just because it was a habit to talk once in a while.

On my eighteenth birthday, I sat alone at my kitchen table, silent except for the tick of the clock. The fake oak didn’t smell like Pledge anymore. No more waxy feel that would make your fingers smell like lemons. Just me and the diploma, a piece of fancy-looking paper hidden behind a sheath of plastic, like it was old-people furniture.

I took the cleaver from the utensil drawer. The handle felt like an anchor, and the blade had a solid heft that made me confident it could split bone. Nothing had been made right or whole by my miraculous healing. A dead mother, for what, an index finger? Regina’s corpse for a useless piece of ear flesh? My friend’s golden shoulder, his pride, our dreams, for what? Being able to pick up a dirty sock? Having an opposable thumb to hold silverware? Everything was taken, and I was left with a power I didn’t want or even need. I didn’t need my hand or ear to heal. In due time, they’d have been capped with scars and the pain would vanish. The parts I needed to regenerate, the pain I needed to subside, were deeper and there forever, untouched by my abilities. Injuries that caused nightmares and bouts of unbridled crying, of looking out the window at a sunny day and being incapable of moving off the couch.

I didn’t want to accept the trade. I hated my new hand and what it represented. I gripped the cleaver. I spread my regenerated hand out on the table and chopped off my regrown fingers with a single strike. They flicked across the table as blood shot out of the mini stumps in gurgles of near-black blood. I watched with a certain affinity for the pain. I stretched the flesh of my ear taut with the thumb and pinky finger of my now-bleeding hand, and used the cleaver’s edge like the bow of a stringed instrument, drawing it back and forth against the tight cartilage until a sufficient piece was severed, comparable to my original loss. I threw the fingers and ear into the garbage disposal, switched it on, then used dishtowels and pressure to stop the bleeding of my hand. I left the blood-soaked dishtowel against the wound and wrapped it with a half roll of duct tape.

For three days, I didn’t leave the house, eating nothing but canned soup and cereal with expired milk. I didn’t bathe, I just slept and watched television and waited, hoping that in a couple days I could remove the makeshift dressings and show God I didn’t want his reparations.

Three days later, my fingers were back, my ear was whole, and the only reminder of those cuts that remained was a new set of white lines tracing the border between who I am and who I used to be.

Excerpted from The Heart Does Not Grow Back © Fred Venturini, 2014