With all apologies to Pacific Rim’s Stacker Pentecost, sometimes the apocalypse doesn’t get canceled. Sometimes entire civilizations are upended; sometimes beloved homes and cities are destroyed, with entire ways of life and methods of interacting with the world shattered. But sometimes one person’s apocalypse is another person’s history–and in the hands of the right author, it can be as viscerally unnerving and cataclysmic as any story set in our own near future showing the end of the world as we conceive it.

Alternately: there’s a disquieting charge that one can get from reading a novel in which modern civilization is pushed to its limits and starts to fray. But even there, some of the same lessons about historical scope can be found. Consider the fact that David Mitchell has offered up two different visions of collapse, one in the very near future in The Bone Clocks, and one a few centuries further onwards in Cloud Atlas. For the characters watching the societal order and technological sophistication to which they’d become accustomed shift into a much more fragile existence, punctuated by the presence of violent warlords, it might look like the last days of humanity. But Cloud Atlas showcases a technologically thriving society existing on that same future timeline years later, and a more primitive society even further into the future. Not all apocalypses are global, and not all of them end the entire world.

Paul Kingsnorth’s The Wake is set around the time of the Norman Conquest of England in the eleventh century CE. Its narrator, a man named Buccmaster, finds himself fighting a guerrilla campaign against the invaders, and moving through an increasingly wracked and unsettled landscape. On one hand, this is the stuff of historical fiction: a moment in which English history was forever altered. On the other hand, it’s an account of history told by people watching it happen from a variable perspective: some of the tension early in the novel comes from the confusion of what, exactly, is going on as the invasion continues. Armies are gathered, but news doesn’t always spread speedily to the corners of the world where the narrator is found, and that sense of intentional confusion is used both to summon tension and to echo the narrator’s fractured psyche.

The Wake is written in “a pseudo-language intended to convey the feeling of” Old English, Kingsnorth writes in an afterword. But in reading a story of a damaged landscape told in a fragmentary tongue that bears some–but not a total–resemblance to the English to which readers are accustomed also echoes Russell Hoban’s post-apocalyptic novel Riddley Walker. It’s a comparison that many critics made when reviewing Kingsnorth’s novel. Kingsnorth himself has referred to Hoban’s novel as “a kind of post-collapse moral. Because if everything does suddenly collapse the thing that a lot of people are going to want to do, because they were brought up in the culture that fell apart, is to get it all back.” He could just as easily be referring to his own book.

That sense of trying to retain a lost sense of normalcy also comes up in György Spiró’s recently-translated novel Captivity. Captivity is about Uri, a member of a Roman Jewish community, who travels throughout the Mediterranean over the course of several decades. As the novel begins, Rome is a comfortable home for him; not long afterwards, upheavals turn much of the population hostile. As Uri travels, he witnesses political upheavals, political corruption, and the rise of Christianity–all signs that the world as he knew it is undergoing a fundamental alteration. Both Spiró’s novel and Kingsnorth’s are set in well-documented reaches of the past, but they’re far from museum pieces. They document a condition that unnerves plenty of people today: the collapse of a civil society into one where random acts of violence abound.

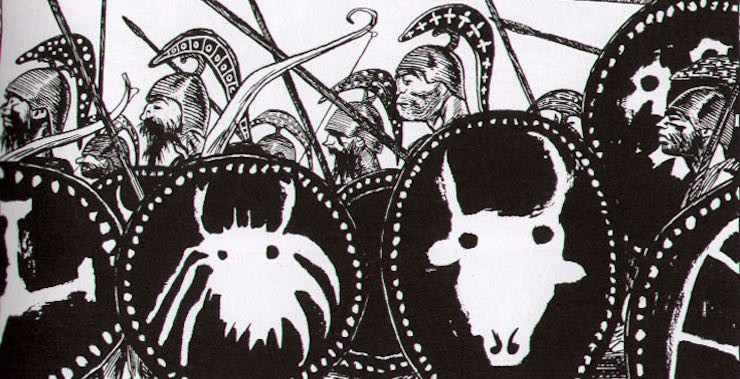

Peplum, a 1997 graphic novel by the French artist Blutch–also newly translated into English–is another example of a post-apocalyptic story of madness and obsession set nearly two thousand years in the past, in and around ancient Rome. In the opening scene, set “[a]t the far reaches of the Empire,” a group of men led by a nobleman named Publius Cimber discover the body of a beautiful women preserved in ice. Soon, several have become obsessed with her, believing her to be alive. A group of crows in the distance laugh, to horrifying effect–a harbinger of the surreal and ominous mood to come. Soon enough, Cimber dies, and his identity is taken over by a young man who will become the closest things this book has to a protagonist; he journeys onward towards Rome, guided mainly by his obsession with the frozen woman and his desire for self-preservation.

Peplum’s tone is intentionally delirious–Blutch’s artwork features nearly every character at their most grotesque, overcome by their obsessions. (And, in some cases, overcome by disease: Publius Cimber’s group is soon infected by a plague, with pustules covering many a face.) But there’s also a nightmarish logic to it: for all that the woman encased in ice whose existence drives most of the plot forward is almost certainly dead, given the hallucinatory tone of the book, nearly anything seems possible. A trio of men debating her status convince themselves that she lives, and the casual way in which they debate her fate is as horrifying as any act of murder or fatal betrayal found elsewhere in the book. But on a more fundamental level, it’s a story in which reality itself seems to be falling apart–where the borders that delineate identity, order from chaos, and life from death have become malleable. The assassination of Julius Caesar occurs early in the book, and that establishes a general sense that this is a world where boundaries have begun to dissolve.

Anxieties over the end of the world as we know it long predate, well, the R.E.M. song of the same name. Books like The Wake, Captivity, and Peplum can remind readers that moments of historical change which might occupy a couple of lines in a textbook represented something far more horrifying to the people living through those moments. These may not be fictionalizations of the actual end of the world, but for those enduring those experiences, they might as well have been.

Top image from Peplum.

Tobias Carroll is the managing editor of Vol.1 Brooklyn. He is the author of the short story collectionTransitory (Civil Coping Mechanisms) and the novel Reel (Rare Bird Books).