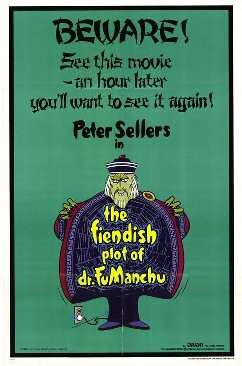

Back in 1980, I saw Peter Sellers’ very last film, The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu, which sadly isn’t very good and was certainly an odd follow-up to the critically-acclaimed Being There (which would have been a much better final film to go out on). But it was my introduction to Dr. Fu Manchu and his arch-nemesis Commissioner Sir Denis Nayland Smith. In the film, Fu Manchu is nearing the end of his very long life and seeking the ingredients to the elixir vitae in order to regain his youth. Standing in his way, his lifelong enemy. Sellers plays both Fu Manchu and Nayland Smith, and the film is notable in that the bad guy wins. Manchu appears at the end, restored to health and youth, and announces his intention to become a rock star. The elder Smith, who has refused his own chance at eternal life, walks away muttering about the “poor, deluded fool,” but even at the time, I thought it was Smith himself who was being foolish.

The movie underscores a lot of what I have come to feel about the characters. But I get ahead of myself.

In 2000, I was the Executive Editor of an Internet start-up called Bookface.com (long since vanished in the burst of the dot com bubble). Bookface was an online publishing venture and we had many tens of thousands of books for online reading, both public domain and publisher-supplied. Among them, the works of Sax Rohmer. I got briefly interested in checking them out, but was put off by the overt racism. Fu Manchu is described by Rohmer as embodying “the yellow peril incarnate in one man,” and I never made it further into the works than encountering that single phrase in a foreword.

Flash forward to a month or so ago, when I became obsessed with the Mountain Goats album Heretic Pride, and most specifically their song & video, Sax Rohmer # 1. Let’s pause and check it out:

Cool, no?

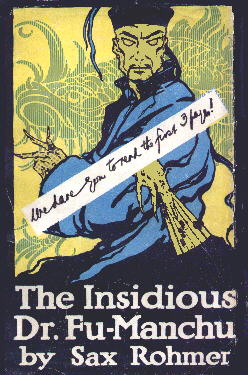

So, after listening to this song a hundred times and memorizing all the lyrics, I went looking up Rohmer on Wikipedia. I already knew that Dr. Fu Manchu was the inspiration for Flash Gordon’s Ming the Merciless, the Shadow’s Shiwan Khan, James Bond’s Dr. No, Jonny Quest’s Doctor Zin, Doctor Who‘s Weng-Chiang, and Batman’s Dr. Tzin-Tzin. What I didn’t know was that he was also the primary inspiration for my favorite Bat-villain, Ra’s al Ghul. To learn that fact, and to see the scope of his influence so clearly enumerated, made me curious again to check out the source material. Add to this my obsession with Stanza for iPhone and instant access to thousands of public domain titles, and I soon had the original 1913 Sax Rohmer novel, The Insidious of Dr. Fu Manchu, in front of me.

Now, before I go any further, this book is overtly racist. And not in the same way that other works of the period, like Edgar Rice Burroughs or Sexton Blake, are colored by the lamentable attitudes of their day. Rohmer was criticized for racism by his contemporaries, and he apparently defended himself by saying that, “criminality was often rampant among the Chinese.” So, I’m not recommending this book. And, in fact, if Rohmer were alive and the book wasn’t public domain, such that no one is profiting financially off of it, I wouldn’t write this post at all. My own interest was specifically to glean insights into how Denny O’Neil created Ra’s al Ghul, and broadly to understand the evolution of the supervillain in popular culture. And Fu Manchu is very definitely one of the first supervillains.

Now, before I go any further, this book is overtly racist. And not in the same way that other works of the period, like Edgar Rice Burroughs or Sexton Blake, are colored by the lamentable attitudes of their day. Rohmer was criticized for racism by his contemporaries, and he apparently defended himself by saying that, “criminality was often rampant among the Chinese.” So, I’m not recommending this book. And, in fact, if Rohmer were alive and the book wasn’t public domain, such that no one is profiting financially off of it, I wouldn’t write this post at all. My own interest was specifically to glean insights into how Denny O’Neil created Ra’s al Ghul, and broadly to understand the evolution of the supervillain in popular culture. And Fu Manchu is very definitely one of the first supervillains.

The full quote, from Chapter Two of The Insidious Dr. Fu Manchu (1913):

Imagine a person, tall, lean and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, a close-shaven skull, and long, magnetic eyes of the true cat-green. Invest him with all the cruel cunning of an entire Eastern race, accumulated in one giant intellect, with all the resources of science past and present, with all the resources, if you will, of a wealthy government—which, however, already has denied all knowledge of his existence. Imagine that awful being, and you have a mental picture of Dr. Fu-Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man.

Intriguing and offensive all at once. I’m particularly puzzled by the “magnetic eyes of true cat-green,” a description that makes me wonder if Rohmer ever actually met anyone Chinese. Elsewhere, Fu Manchu’s eyes are actually said to glow at night, and to have a sort of filmy secondary lid which is seen sliding across his iris, which sounds like a cross between Spock’s Vulcan “inner eyelid” and the tapetum lucidum of felines. In fact, this weird physicality actually helped me get through the book, as I came to view Fu Manchu as some sort of alien or supernatural being, and not a true Asian at all. Still, lines like “No white man, I honestly believe, appreciates the unemotional cruelty of the Chinese” are so distasteful that I almost quit reading, and again, would have if the work weren’t approaching a hundred years old. I don’t even like the word “inscrutable,” because I only ever see it applied to Asians, and indeed, it’s all over this book (and might even be the origin of that association for all I know). My wife is Mandarin, from mainland China, and I assure you she is perfectly scrutable, and while she does have a fondness for pinching, she’s hardly unemotional when she does it. No, these are all the trappings of a man who refuses to see people as people, when, as travel in Asia or really travel anywhere will teach you, people are people everywhere you go.

Now, as to the book itself, it (and the next two Fu Manchu novels), are narrated by a Dr. Watson character called Dr. Petrie, but Petrie is more actively involved than Watson ever was, often driving the action and even going off on his own a time or two. Petrie is writing in his study when Nayland Smith, formerly of Scotland yard, recently of Burma, bursts in, enlisting him to help prevent an assassination. We realize that quite a few British gentlemen, all associated with India in some way or other, are being targeted by secret operative of the Chinese government, our title character. Smith and Petrie race to the scene, arriving too late, but not before Petrie, standing guard outside, is approached by a mysterious woman who warns him away. She is later revealed to be Karamaneh, an intoxicatingly beautiful Arabic woman, who is both a slave to Fu Manchu and one of his best assassins. Now, this is where my ears pricked up, because Karamaneh falls instantly in love with Dr. Petrie, and what follows is a succession of cliffhangers in which Petrie and Smith blunder into a succession of death traps and Karamaneh arrives to save them. She won’t abandon Fu Manchu, who has a mysterious hold over her, but neither will she allow her beloved Petrie to come to harm. Starting to sound familiar?

This is it, the inspiration for Ra’s al Ghul’s daughter Talia (also Arabic, deeply in love with Batman, but unable to betray her father). Karamaneh was combined with Fah lo Suee, the daughter of Fu Manchu who was introduced in later books. A deadly supervillain in her own right, Fah lo Suee often fought with her father for control of his organization. She also fell in love with Nayland Smith. O’Neil combined the two women, added a touch of On Her Majestry’s Secret Service, and viola, Ra’s al Ghul and Talia are born.

Anyway, Smith and Petrie try to outwit assassination after assassination, often showing up to warn the victim and then camping out with him while they await the attempt. Some times they are successful, other times Fu Manchu manages the kill by means of mysterious poisons that have been secreted into the victim’s residence at an earlier date. And this, combined with the villain’s bizarrely green eyes, makes me think that Fu Manchu is also the inspiration, at least in part, for the Joker, because that green-eyed maniac’s first appearance, in Batman #1, is oddly similar, with the Joker announcing his intention to kill a succession of victims, Batman and the police staking out the house, and the Joker largely accomplishing his kills in the same manner.

About midway through the book, Smith and Petrie takes the fight to Fu Manchu, ferreting out his hideouts in an opium den, a mansion, and a grounded ship, destroying each one in turn. Finally, Karamaneh appears to lead Petrie to Fu Manchu’s primary base of operations, an opulently-appointed suite of apartments, in which we learn the nature of his hold over the beautiful assassin. It seems that Fu Manchu, whose medical knowledge “exceeds that of any doctor in the Western world” possesses a strange serum that can induce seeming-death in a person and reawaken them later. He holds the life of her brother Aziz suspended in this way. Karamaneh procures the serum for Petrie and induces him to free her brother, at which point she is no longer in Fu Manchu’s sway.

Fu Manchu himself is then seen locked seemingly in an opium delirium (he is an addict, and Petrie pronounces the habit will soon kill him). But when Smith, Nayland and an Inspector Weymouth approach to apprehend him, they fall through a trap in the floor (the book has a lot of these) into a den where Manchu, a brilliant fungologist, has cultivated a giant variety of empusa muscae that attacks humans (this shows up in Batman too).

Eventually, they free themselves, and Smith and Nayland are witness to a battle on the Thames between Weymouth and Fu Manchu. Both are apparently drowned, but not before Weymouth is injected with a serum that Manchu has developed that drives men mad.

Weymouth resurfaces, coming home to knock on his own backdoor at one a.m. each night, but he is a gibbering maniac (again with the Joker and his “Joker venom,” plus a little bit of Professor Hugo Strange.)

Later, a completely chance encounter reveals that Fu Manchu has survived. He is apprehended, and Smith asks him if he will restore Weymouth to sanity, though Smith adds that “I cannot save you from the hangman, nor would I if I could.”

Fu Manchu replies that, “What I have done from conviction and what I have done of necessity are separate—seas apart. The brave Inspector Weymouth I wounded with a poison needle, in self-defense; but I regret his condition as greatly as you do.” He then agrees to cure the man, on condition that he be left alone with him, as he refused to reveal his secrets. This is arranged, and shortly, a confused by hale Weymouth emerges from the house, only for the building itself to erupt in unnatural flames. Naturally, no bones are ever found among the ashes.

But a note is, in Inspector Weymouth’s pocket, in which Fu Manchu announces that he has been recalled home “by One who may not be denied.” He goes on to write that “In much that I came to do I have failed. Much that I have done I wold undo; some little I have undone,” and adds the enigmatic “Out of fire I came—the smoldering fire of a thing one day to be a consuming fire; in fire I go. Seek not my ashes. I am the lord of the fires! Farewell.”

Of course he comes back. For twelve more books. And that death and resurrection should also remind one of Ra’s al Ghul. Meanwhile, this novel ends with Petrie wondering if sending Karamaneh off on a ship home wasn’t a mistake, followed by the news that Nayland Smith has extended Petrie an invitation to join him on his forthcoming trip to Burma!

So, where did it leave me? Exactly where the Peter Sellers movie did. I really like Dr. Fu Manchu. As apparently does Dr. Petrie, who goes out of his way a dozen times to tell us what a genius he is, an unparalleled doctor and chemist, and probably the smartest man then alive. In fact, it’s mostly Smith who’s the racist and Petrie, falling in love with and in later books marrying an Arabic woman, who seems a good deal more broad-minded. Fu Manchu himself seems to regard Petrie as more of an equal-than-obstacle and Smith as the reverse. Even Rohmer seems to step back from his racism a time or two. After establishing Fu Manchu as an agent of a foreign power, he modifies this opinion and has Smith say that he thinks Fu Manchu represents neither the “Old China” of the Mandarin ruling class, nor the “young China” of “youthful and unbalanced reformers” with “western polish” —but a mysterious and secret “Third Party.” This seems a move to distance him from any real actions of the Chinese country or government. Just as Smith’s bizarre recounting of a (I’m guessing completely fabricated) Chinese legend that children born near graveyards can become possessed of evil spirits under certain circumstances and that Fu Manchu’s own birth occurred under such circumstances seems an attempt to distinguish him from regular Chinese persons, i.e., those not possessed of evil spirits. And then Fu Manchu disappears in the midst of an act of charity, and leaves a note of regret for some of his actions. So, basically, I like Fu Manchu, even as I dislike Nayland Smith and his creator, Sax Rohmer. It’s almost as if the character broke free of the limits of his own creator, as indeed he did, given the wide scope of his influence recounted above. And it’s no wonder he has found himself adapted into the works of Philip José Farmer, Kim Newman, and George Alec Effinger. Fu Manchu shows up, as himself, in both DC and Marvel comics, and is the unnamed “Devil Doctor” of Alan Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. He is named in numerous songs, including ones by the Kinks and Frank Black of the Pixies, and even has a band named after him. He’s been featured in over ten films (five times portrayed by the great Christopher Lee), and Nicolas Cage even cameos as Fu Manchu in Grindhouse. Given all this, and the numerous connections to the Batman legend, I’m glad that I read The Insidious Dr Fu Manchu. I feel like I’ve filled in a glaring hole in my pulp education. But I’m gladder still to live in a world where people are generally more sensitive to such negative stereotyping. Ignorance of Fu Manchu was a hole in my pop cultural education, and my pop culture is rooted in the 20th Century, where the “insidious” Doctor incontestably casts a long shadow. But this is the 21st Century, an enlightened time when hopefully we trust Asian actors to portray their own race better than Englishmen and David Carradine, and as such it’s a time for new myths, new heroes and new villains. So, if you want to know everything there is to possibly know about pulp fiction, Dr. Fu Manchu is certainly on your list, but if you aren’t a child of the 20th century, if you are growing up on the television, cinema, comic books and Internet culture of today, or even if you are older but you are just starting your genre exploration, there are a lot better, newer, and less offensive places to start. And I certainly wouldn’t recommend starting here. Still, I’d be lying if I said there wasn’t something compelling—even magnetic—about the brilliant and evil, yet very honorable, Doctor and his hypnotic, penetrating, and altogether inexplicable green eyes.

So, where did it leave me? Exactly where the Peter Sellers movie did. I really like Dr. Fu Manchu. As apparently does Dr. Petrie, who goes out of his way a dozen times to tell us what a genius he is, an unparalleled doctor and chemist, and probably the smartest man then alive. In fact, it’s mostly Smith who’s the racist and Petrie, falling in love with and in later books marrying an Arabic woman, who seems a good deal more broad-minded. Fu Manchu himself seems to regard Petrie as more of an equal-than-obstacle and Smith as the reverse. Even Rohmer seems to step back from his racism a time or two. After establishing Fu Manchu as an agent of a foreign power, he modifies this opinion and has Smith say that he thinks Fu Manchu represents neither the “Old China” of the Mandarin ruling class, nor the “young China” of “youthful and unbalanced reformers” with “western polish” —but a mysterious and secret “Third Party.” This seems a move to distance him from any real actions of the Chinese country or government. Just as Smith’s bizarre recounting of a (I’m guessing completely fabricated) Chinese legend that children born near graveyards can become possessed of evil spirits under certain circumstances and that Fu Manchu’s own birth occurred under such circumstances seems an attempt to distinguish him from regular Chinese persons, i.e., those not possessed of evil spirits. And then Fu Manchu disappears in the midst of an act of charity, and leaves a note of regret for some of his actions. So, basically, I like Fu Manchu, even as I dislike Nayland Smith and his creator, Sax Rohmer. It’s almost as if the character broke free of the limits of his own creator, as indeed he did, given the wide scope of his influence recounted above. And it’s no wonder he has found himself adapted into the works of Philip José Farmer, Kim Newman, and George Alec Effinger. Fu Manchu shows up, as himself, in both DC and Marvel comics, and is the unnamed “Devil Doctor” of Alan Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. He is named in numerous songs, including ones by the Kinks and Frank Black of the Pixies, and even has a band named after him. He’s been featured in over ten films (five times portrayed by the great Christopher Lee), and Nicolas Cage even cameos as Fu Manchu in Grindhouse. Given all this, and the numerous connections to the Batman legend, I’m glad that I read The Insidious Dr Fu Manchu. I feel like I’ve filled in a glaring hole in my pulp education. But I’m gladder still to live in a world where people are generally more sensitive to such negative stereotyping. Ignorance of Fu Manchu was a hole in my pop cultural education, and my pop culture is rooted in the 20th Century, where the “insidious” Doctor incontestably casts a long shadow. But this is the 21st Century, an enlightened time when hopefully we trust Asian actors to portray their own race better than Englishmen and David Carradine, and as such it’s a time for new myths, new heroes and new villains. So, if you want to know everything there is to possibly know about pulp fiction, Dr. Fu Manchu is certainly on your list, but if you aren’t a child of the 20th century, if you are growing up on the television, cinema, comic books and Internet culture of today, or even if you are older but you are just starting your genre exploration, there are a lot better, newer, and less offensive places to start. And I certainly wouldn’t recommend starting here. Still, I’d be lying if I said there wasn’t something compelling—even magnetic—about the brilliant and evil, yet very honorable, Doctor and his hypnotic, penetrating, and altogether inexplicable green eyes.

And on that note, I’ll let the Mountain Goats take us out:

Bells ring in the tower, wolves howl in the hills

Chalk marks show up on a few high windowsills

And a rabbit gives up somewhere, and a dozen hawks descend

Every moment leads toward its own sad end

Yeah ah ahShips loosed from their moorings capsize and then they’re gone

Sailors with no captains watch awhile and then move on

And an agent crests the shadows and I head in her direction

All roads lead toward the same blocked intersectionI am coming home to you

With my own blood in my mouth

And I am coming home to you

If it’s the last thing that I do