I’ve been in some sort of pain, every day, since I was 9.

Now let me hasten to add to that sentence that I have it way better than a lot of other people. My pain has been manageable, or at least ignorable, for much of that time. It might hurt to walk, but I can still walk, I don’t have to navigate this society’s reprehensible treatment of people who need different mobility devices. For the most part my disabilities don’t stop me from doing things I want to do, because what I want to do is sit still with a movie or a book or a pen. (My arthritis hasn’t gotten so bad that I can’t hold a pen yet, though I do need to take more breaks than I used to.)

But the pain is still there, is my point. The pain is there in my body, for me to navigate. It shapes every decision I make, every day. It has shaped most of my life.

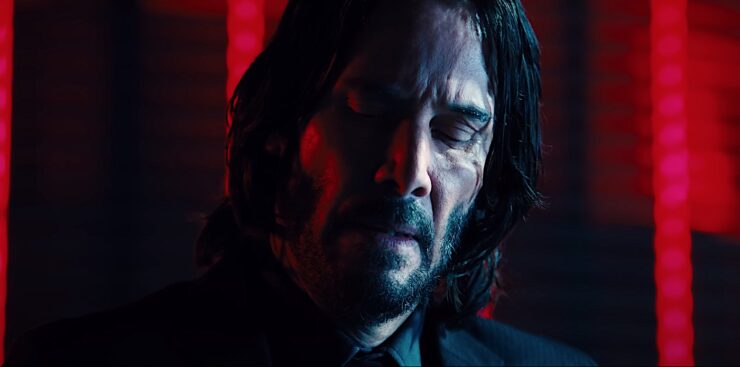

And as I went into the last third of John Wick: Chapter 4, I realized that the pain has also shaped my love of these movies.

[Some spoilers for John Wick 4]

The thing that sets Wick apart from other action movies is the relentlessness. In the first few films especially, John Wick walks into each new battle the way I used to walk into a 9-hour shift on my feet at a deli—it’s gonna hurt, sure, but we’ll get through it one goon/customer at a time. (Maybe you think I’m being absurd with this comparison, but I’ll say this: I also ended each day smelling of meat and blood, and at least John Wick never had to endure the horror of slicing pre-packaged deli headcheese.)

Other than a few brief moments of rage or sorrow, the primary emotional tone is weariness. Exhaustion, determination, compartmentalizing. Each new assassin is another micro-task – if I just get through this guy I can get to the end of the hall. If I just snap this violinist’s neck, I’m almost clear of the train station. If I can just shoot these three guys, I can take their clips, reload, and make it to the next modern art gallery.

The reloading is miraculous. The way he tracks his bullets, clearly counting them down as he goes, the way he times it out so he can duck into a corner and load a new clip, calmly, muscle memory at work, his focus entirely on that task until he swings back out of cover to shoot. The way he shoots – precise, aimed, the bullet to disorient the opponent, knock them back or cause them pain, the next two or three to incapacitate and/or kill, the headshot after they can’t hurt him as he’s moving on to the next one—crossing a t so it won’t come back to haunt him later. Remember when people with chronic pain started measuring their abilities with spoons? Like, “I only have this many spoons today, so I have to keep an eye on them as I use them”? John Wick, I would argue, has bullets.

He’s not motivated by rage, and as much as he is a little superhuman, he’s also not invulnerable. He limps, he’s winded, he feels pain, but the plot never gives him a chance to stop or heal. The first three John Wick movies take place over, what, a week or two? Santino D’Antonio arrives at John’s door the night after he’s defeated Viggo. John Wick 2 sees John traveling between New York, Rome, and back, fighting his way through Santino’s goons, Cassian, rando assassins, Ares, and Santino himself all over the course of a few days. The closest thing to a break he gets is a conversation about Hell with Gianna as she slits her wrists. Once John finally gets back to the rubble that used to be his house, there’s Charon, telling him to come straight back to New York to meet Winston in Central Park. He’s declared Excommunicado, and John Wick 3 begins about 20 minutes after the second installment ends. John Wick 3 takes place over like a week, right? He fights his way to the Ruska Roma, gets his ticket torn, goes to Morocco, walks in the desert for three days that we see, swears fealty to the Table, goes back to NYC again, and then fights on Winston’s behalf for a single night, with the parley happening in the early morning. As John Wick 4 opens, we don’t know how long he’s been training with the Bowery King, or how long his hunting of the Elder takes, but the action in New York, Osaka, Paris, and Berlin, is, once again, all done over a few days.

So also he’s jet-lagged for all this.

I’m pointing it out because across the entire quadrilogy, John only receives a few moments of rest, and maybe two showers. Presumably there is travel time between the continents (and Continentals) that we don’t see, but if John is onscreen, he’s fighting, ever more exhausted. The first film ends with him limping home, self-stapled and seeping blood from multiple wounds, with Dog. The second ends with him running through Central Park, Dog at his side, as all the assassins’ phones light up with his Excommunicado status. And the third ends with that Looney Tunes fall from the roof, and John in a bleeding heap at the feet of the Bowery King.

But the key here is that it ends with John running, John rescuing Dog, John giving the Bowery King the finger. Each film ends with John choosing to keep fighting.

How we do anything is how we do everything.

In a way I love watching these movies because John Wick does things I will never be able to do. I used to be an okay shot, but I was never a John Wick-level shot. (And my scrawny hands would never be able to reload like that.) Even as a kid I couldn’t twist or roll or slide on my knees or do any of the martial arts technique that informs John Wick’s every step. Even the most basic physical grace is already a fantasy to me. And because the carnage is all, ultimately, in the service of a murdered puppy, I can kind of check my pacifism at the theater door. Because it’s all underpinned with guilt, nihilism, and, seemingly, a series-wide belief in the certainty of Hell, I can kind of meditate on violence and its consequences.

But beyond that. John Wick moves through the world the way I move through the world. Every step is an effort. Constantly scanning for exits, the easiest path, how to move around people without getting hurt. Exhausted. Grieving, sure, but that pain has to stay in a box so you can get through this next hallway, or staircase, or gallery.

When my—actually, wait. That’s too personal.

Here, have a list of references/easter eggs from John Wick 4 instead:

- When the Bowery King blows his match out, the cut to the desert sunrise matches The Greatest Shot Ever from Lawrence of Arabia.

- In the opening scene, the Bowery King is shouting lines from Dante’s Inferno (talk about prose-forward writing!); John later fights his way through a Berlin club called Himmel Hölle—Heaven Hell. (Which I guess makes Paris… Purgatory? Maybe Oscar Wilde was wrong?)

- The radio broadcast is a nod to The Warriors, and the station ID is WUXIA.

- The duel is a riff on Barry Lyndon.

- When the King lights a highly choreographed fire on the floor of John’s training room, do you think that’s calling back to The Crow? I ask because John Wick director Chad Stahelski doubled for the much-missed Brandon Lee on that film.

- “Dragon’s Breath” is also a weapon in Constantine, and when it’s used in John Wick 4, there’s a ridiculously ornate shattered mirror that looks exactly like the one from the exorcism in Constantine.

- The Harbinger looks like Father Merrin from The Exorcist. (And like John, he’s also missing his ring finger.)

OK, now that that’s out of my system—and please tell me any references that I missed—let’s talk about religion in the John Wick series.

The fabulous Gavia Whitelaw Baker has talked about the religious underpinning of the series, and the idea that John’s mourning for his wife is his religious practice. I like this read, and I think it’s underlined a few times. Back in the first movie, John tells Viggo Tarasov that his puppy represented a chance to “grieve un-alone”—the dog wasn’t there to cheer him up, she was there to grieve with him. This is what Ioseph Tarasov took from him. It’s one of the only moments that John’s facade cracks, but he quickly channels his raw pain back into rage. And now in John Wick 4, when John enacts a simple, real-world religious practice by lighting a candle in a church, he makes it explicit that he’s reaching out to Helen in this moment, not any overarching deity.

But there’s another aspect to the religious imagery, so prominent throughout. I kept thinking about The Fast and the Furious, the other huge, family-oriented, globetrotting action franchise of the last decade. The F&F-verse is nominally Catholic, but in that way of a giant Italian family—maybe you go to church sometimes, but you always wear your religious icons, and you absolutely show up for the mid-afternoon Sunday meal. And as in everything in an F&F movie, religion is about FAMILY. It’s part of the general spectrum of backyard barbecues and weddings and honoring motherhood and stealing VCRs as a group and everyone coming together each time a supervillain shows up plotting your death. It’s in the fabric.

Not so in the Wick-verse.

First of all, in John Wick churches are just as potentially dangerous as any other site. The only safe space is the continental. The hotel is sacred, not the church—the church is where laundered money is held, where the priests are liable to whip out shotguns. Rosaries are not holy relics, they’re tickets to be cashed in, the same as the gold coins that make up the Wick-verse’s currency.

But the other thing it serves is a constant drumbeat of suffering. Because this isn’t triumphalist Protestantism or even family-friendly Catholicism, it’s that darker streak of the Catholicism, or, more often, Russian Orthodoxy. This is an action film series whose director cites Dante as enthusiastically as Sergio Leone and Yuen Woo-ping.

The religious imagery of the Wick-verse isn’t hinting toward respite or salvation or any of that; it’s shorthand for a worldview that accepts suffering and loss as a part of life, and Hell as a reality. Much like my other favorite Keanu Reeves movie, the concept of damnation is spoken of constantly—I’d say casually, but it’s not that. Everyone takes it quite seriously, and as a foregone conclusion. The life they’re in only leads to one thing.

But at the same time, in John Wick 4, the story is book-ended with religious imagery that does offer solace. Kind of. When John goes back to the Ruska Romani to ask them to take him back, it’s via an orthodox church (termed as a safe house in Mr. Nobody’s journal). And sure, the priest shoots john, but after he completes his task and comes back, his adopted sister gives him the crest, in the church, under the eyes of multiple Orthodox priests. After the Marquis and John agree to a duel at dawn, John goes to a Catholic church to “say hello” to his wife. This is one of the rare moments in the quadrilogy with no violence, no ambushes, nothing. John is actually allowed to sit and rest for a moment. When Caine joins him, their conversation isn’t exactly comforting, but I think Caine means it when he says “it’s nice, to sit with a friend”.

And, of course, the whole adventure ends with John’s pilgrimage up the 222 steps to Sacre Coeur. (I’ve walked up those steps and it hurt like a motherfucker, and I didn’t have the entire assassin underworld trying to kill me while I did it.) I’ve done exactly that thing though – looking up multiple flights of stairs (usually somewhere in the bowels of the NYC subway system) realizing that I have to walk up them, knowing that I can’t and knowing that I have to do it anyway.

Watching him make it, get all the way to the top, and then GET KNOCKED BACK DOWN? But then he gets up and does it again? Does it make sense to say that I both identified with, and was inspired by, this ice-cold hitman? That in my pain I related to him? Am I making any sense?

But there’s another element to this. I’ve seen the movie twice now, in theaters, and that long rib-shattering, torturous roll was when the atmosphere changed. That was when the pain of this series transformed, the way pain sometimes does, into a whole other transcendental thing. Because I, along with everyone else in the theater, exploded with laughter.

As much as these films are about suffering, they are a joyful experience to watch. At a certain point the absurdity of the physical pain, the relentless enemies, all the reloading, the deadpan humor that leaks from Keanu Reeves’ every pore—it takes all that pain and makes it fun. We’re all in it together. Me trudging up the subway staircase as the train I need pulls away, John drifting his way around the Arc de Triomphe—we’re the same, really.

The pain is always going to be there. Hell, it’s only going to get worse. But the trick is not minding that it hurts, and looking for the joy to be had on the way up the stairs.