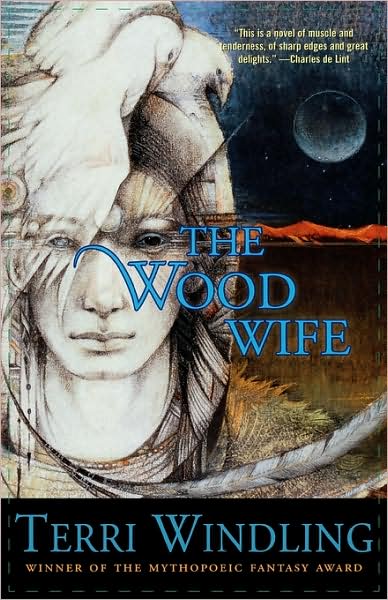

Terri Windling’s The Wood Wife (1996) is another rural fantasy, rather than an urban one. It’s the story of a forty-year old woman rediscovering herself as a person and a poet when she comes to the mountains outside Tucson and encounters the local inhabitants, human and otherwise, and begins to unravel their secrets. There’s a romance in it, but it doesn’t fit with the kind of thing usually considered as paranormal romance either.

It is a great book though, one of my favourite American fantasies. It doesn’t make it all up like Talking Man, it walks the more difficult balance of using both European mythology and the mythology of the people who were there when the settlers came. Windling makes it work, and in the process writes an engrossing novel that I can’t put down even when I know what’s going to happen. This is one of those books that hits a sweet spot for me where I just love everything it’s doing—it’s the sort of book I’m almost afraid to re-read in case it’s changed. The good news is, it hasn’t.

I called it an American fantasy, but what I mean is that it’s a regional American fantasy. I think the reason there isn’t one “American fantasy” is because America is so big. So there are regional fantasies like this and like Perfect Circle, and there are road trip fantasies like Talking Man and American Gods, and they have the sense of specific places in America but not the whole country because the whole country isn’t mythologically one thing. I might be wrong—it isn’t my country. But that’s how it feels.

In any case, The Wood Wife is doing one place and time, and the sense of the Rincon hills and Tucson and Arizona comes through strongly. Maggie Black has been a wanderer, growing up in Kentucky, educated in England, living in New York and California and Amsterdam. She’s forty years old when she comes to the mountains of Arizona as an outsider who has inherited a house and a mystery from a dead poet. It’s so refreshing to have a middle-aged woman heroine, one who’s already successful in her career when the book starts, who is done with one marriage and ready to move on, one with experience, one with a talented female best friend. Coming of age stories are common, but mid-life stories about women are surprisingly rare.

All the characters are great. They also belong very specifically to their place and time. The humans are mostly the kind of people who live on the artistic fringes, some of them more successfully than others—I know a lot of people like them. One of the central things this book is doing is showing a variety of relationships between romantic partners who have their own artistic work, and different ways of supporting that within a relationship. There’s art and life and the balance between them, and then there’s magic getting into it—we have magical creatures as literal muses, and the story explored what becomes of that.

Windling is best known as the editor of some of the best fantasy and fantasy anthologies of the last few decades. She’s one of the most influential editors in the genre—and still I wish she’d find more time for her own writing because this book is just marvelous.

As well as a precise place, time and social context it’s also set in a localised mythological context. It’s the book I always point to as doing this thing right, of showing a mythological context in which there were people and their magical neighbours living in the region and then there were Europeans and their magic coming in to that. Too many fantasies set in the New World use European mythology as if the European settlers brought it into a continent that was empty of any magical context beforehand. Windling doesn’t do that. Nor does she deal with the mythology of the Native Americans as if it was a familiar European mythology. This story feels as if it came out of the bones of the land.

Best of all Windling goes at all this directly, aware of what she’s doing. The story is about two generations of painters and poets who come from elsewhere to the Rincons, and cope with living in and artistically rendering the land in their own way. First there’s the English poet Davis Cooper and his partner the Mexican painter Anna Naverra, who we see in memory and in letters that run through the text, grounding it in twentieth century art and literary history. Then there’s Maggie, also a poet, and the painter Juan del Rio. This is Maggie:

“I’ve studied Davis Cooper as an English poet. Born and raised in the West Country. So when I read his poems I see English woods, I see the moor, and hedgerows, and walls of stone. And then I drive up here,” she waved her hand at the dry land around them, “and I realise that these are the woods he’s been talking about all along. These hills. This sky. Now I’m reading a whole different set of poems when I look at Cooper’s work.”

And Davis, whose life and letters run through the book:

I need a land where sun and wind will strip a man down to the soul and bleach his dying bones. I want to speak the language of stones.

Anna and Davis and Maggie and Juan all interact with the spirits of the land directly, and are changed in their different ways. There are people who can transform into trees or coyotes, there’s the fascinating mystery of the spiral path, and the whole thing ties together beautifully. It feels real.

And it’s in print, for once, so absolutely nothing stops you from buying it this moment and reading it for yourself.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

Terri Windling’s column was the main reason I went to the lengths of maintaining an international subscription to Realms of Fantasy, and this book has been hovering around my wishlist for a while ^^

I can see my copy, with its startling pink spine, from where I’m sitting. I bought it on a whim several years ago because I had learned that her name on a book as editor* meant it would be good, and thought I’d see whether that extended to her own writing–and it did!

*I first noticed her name in connection with the Fairy Tales books.

I think talking about rural as opposed to urban fantasy is splitting hairs. The best description of “urban” as a modifier I’ve come across was in a book on gothic fiction. The distinction was made between traditional gothic (Radcliffe, etc.) and urban gothic (Frankenstein, etc.). Urban was taken to mean “recognizably modern” at the time the novel was written – an industrialized and scientific world with modern cities, even if that was not the specific setting of the work.

MaryArrrr: “Urban” means “of or pertaining to towns”, and it seems like an inappropriate label to put on a story resolutely set in the countryside. I’m not claiming there’s a thing called “rural fantasy”, just that not all modern-setting fantasy is in fact urban.

Hmmm. I was trying to sell Talking Man to my doesn’t-read-much-genre sister as ‘Ozark fantasy,’ [“like the Silver John stories,” I said] but she wasn’t buying. I did get her to read Perfect Circle, though, so the experiment was not a total failure. ‘Rural Fantasy’ may be a better sell.