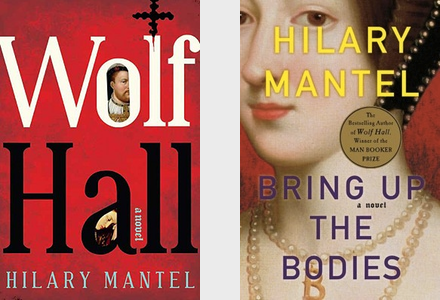

For the last year I’ve been telling everyone who will stand still long enough to listen that if they’ve got any interest in Tudor-era historical fiction, they need to read Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. A thoroughly deserving winner of the Booker Prize, Wolf Hall follows the rise of Thomas Cromwell: blacksmith’s son, secretary to Cardinal Wolsey, and after Wolsey’s fall, secretary to King Henry VIII himself. I couldn’t get enough of this beautifully written book, and I’ve been looking forward to the sequel, Bring Up the Bodies, out this week, with considerable anticipation.

You may have seen Cromwell before as the villain of Robert Bolt’s A Man For All Seasons, “subtle and serious

an intellectual bully” as Bolt describes him, a man who enjoys holding a hapless underling’s hand in a candle to make a point. Or you might have seen him portrayed by James Frain in The Tudors (or à la Kate Beaton, “Sexy Tudors“); at least in that farrago he is less outright  villainous and more interesting in his machinations—though Frain is infinitely more dashing in looks than Hans Holbein the Younger’s portrait suggests that the real Cromwell was.

villainous and more interesting in his machinations—though Frain is infinitely more dashing in looks than Hans Holbein the Younger’s portrait suggests that the real Cromwell was.

Mantel, by her own account, “couldn’t resist a man who was at the heart of the most dramatic events of Henry’s reign, but appeared in fiction and drama—if he appeared at all—as a pantomime villain.” She was attracted to Cromwell as a subject because “he came from nowhere. He was the son of a Putney brewer and blacksmith, a family not very poor but very obscure; how, in a stratified, hierarchal society, did he rise to be Earl of Essex?” In a certain respect, he is not dissimilar to the protagonists of her other great work of historical fiction, the sprawling French Revolution epic A Place of Greater Safety—men from humble beginnings, grown to greatness through intelligence, tenacity, and not a little good fortune in being in the right place at the right time.

What was originally planned as a single volume has, due to the expansiveness and depth of its subject and his times, grown into a trilogy. Wolf Hall opens with Cromwell as a boy, suffering a beating at the hands of his vicious father, and traces his career to Wolsey’s side, and thence to Henry’s. Here he is assigned myriad duties and titles with access attached—the Master of the Jewels, Chancellor of the Exchequer, Master of the Rolls, and eventually Master Secretary—and his efforts help achieve Henry’s split from Rome, his divorce from Katherine of Aragon, and his marriage to Anne Boleyn. Cromwell also, not entirely willingly, brings down Sir Thomas More, who in Mantel’s depiction is a severe religious fanatic, “some sort of failed priest, a frustrated preacher”, as Cromwell thinks of him. By the time of More’s execution, Henry has already begun to tire of Anne, who has disappointed him by not bearing a son. Cromwell, eyes ever forward, is nudging Henry gently in the direction of Wolf Hall, the home of the Seymour family and their daughter Jane.

Bring Up the Bodies is a shorter, tighter book—it begins a handful of months after More’s death and concludes the following summer with another beheading: Anne Boleyn on her knees before the headsman. The works are all of a piece, however, and you really can’t read the new book without having read Wolf Hall; seeds sown in the first volume blossom and bear fruit here—some poisonous. Wolf Hall features an entertainment at Henry’s court that is put on after Wolsey’s fall, in which the cardinal, played by the court jester, is mocked and dragged off to a pantomime Hell by a quartet of devils, played by four sporting young noblemen of the court. Their identities and Cromwell’s long, perfect memory become very important in Bring Up the Bodies and in the downfall of Anne Boleyn.

In Mantel’s hands, Cromwell is a subtle, intelligent man who started rough, learned refinement, and takes his work very seriously. It doesn’t matter what that work is—he may be tallying up the value of a bolt of cloth at a glance, assessing the material wealth of the monasteries to channel it into other coffers (Cardinal Wolsey’s first, King Henry’s next), passing legislation in Parliament, or plotting to bring down a queen. He can easily be seen as an opportunist, and certainly his enemies see him as exactly that—when he enters Henry’s employ after Wolsey’s disgrace, many think that he’s turned his back on his old master, sold him out.

In fact, Cromwell has learned well Wolsey’s good advice about how to appease the king—and seen which way the wind was blowing, to be sure. But even as he’s trying to figure out how to disentangle Henry from Anne—after having spent the entire previous book working so hard to bind them together—he still thinks with love of his old friend and master. And perhaps he is motivated by that love and by old grudges against those who brought about Wolsey’s fall in ways that he will not or cannot admit even to himself.

He is a curiously modern figure in the Tudor world, a respect in which Mantel occasionally walks the delicate border of anachronism. He would say he is a man of faith, but a secular heart beats within his fine clothing; he detests the hypocrisy of the church institutions and is more than pleased to appropriate what he sees as ill-gotten monastic wealth for the good of the crown. He talks freely to the ladies of the court—not to woo or flatter, but to gain information; his respectful attitude toward women is a source of bemusement to men like the Duke of Norfolk. “What’s the use of talking to women?” Norfolk asks of him at one point in Wolf Hall. “Cromwell, you don’t talk to women, do you? I mean, what would be the topic? What would you find to say?”

Envious of his status and of the extent to which he has the king’s ear, the nobles of Henry’s court never miss an opportunity to remind Cromwell of his low birth, and not in complimentary fashion. “Get back to your abacus, Cromwell,” snarls the Duke of Suffolk, when Cromwell has crossed him. “You are only for fetching in money, when it comes to the affairs of nations you cannot deal, you are a common man of no status, and the king himself says so, you are not fit to talk to princes.”

Mantel nests the reader within Cromwell’s busy brain; the limited third person style is at first slightly disorienting, in that sometimes you find yourself stumbling over exactly who the pronoun “he” refers to at any given time. (Hint: It’s usually Cromwell.) But soon you slip into the rhythm of Mantel’s extraordinary, elegant prose; language that guides you through the story like a steersman’s light hand on the tiller. She has a trick at times of pausing the action for a moment’s thought or reflection, a meditation on what has just happened. When Lady Rochford—Anne’s bitter, conniving lady-in-waiting and sister-in-law—makes insinuations to Cromwell about the uses of Anne’s bedchamber, we have this:

What is the nature of the border between truth and lies? It is permeable and blurred because it is planted thick with rumour, confabulation, misunderstandings and twisted tales. Truth can break the gates down, truth can howl in the street; unless Truth is pleasing, personable, and easy to like, she is condemned to stay whimpering at the back door.

Is this Cromwell? Is it Mantel, speaking through Cromwell? Whatever it is, it’s classic Mantel prose—beautifully turned, with a vivid metaphor and spinning neatly on a point of perfect observation, like a top, and it informs that which comes before and all that comes after.

She surrounds Cromwell with an enormous cast of characters as vivid as he, from the charismatic, temperamental king, to the bright young men who are Cromwell’s own secretaries and confidants, to Cromwell’s own family, including the wife and daughters who die of sweating sickness in Wolf Hall, all the way down to a Welsh boatman whose coarse talk about the relations between Anne and her brother in Wolf Hall is echoed by the gossip of Anne’s ladies in Bring Up the Bodies.

Anne herself is dazzling—intelligent, petulant, thoroughly ambitious, and with a ferocious will that seems unbreakable until at last she is brought to the Tower of London, abandoned by Henry and at the mercy of men who will find her guilty of any crime they can name, because she has become inconvenient to the king. There are many conversations in this book in which men discuss in excruciating detail the bodies of women—women who, despite their status, are even more alone and powerless in the face of those men than the humblest merchant’s wife or peasant woman.

By the end of Bring Up the Bodies, Anne has been buried in an arrow-chest beneath the stones of the chapel of St Peter Ad Vincula, and Henry has married his modest new bride, Jane Seymour (who at times comes across as a kind of Tudor Gracie Allen, giving serious, deadpan answers to humorous questions, and who may be more in on the joke than she lets on). Cromwell is at the peak of his powers, but a student of history—or, for that matter, a viewer of “Sexy Tudors” who made it to the end of Series 3—knows that his days are numbered. And Cromwell himself is well aware of the precariousness of his position, and has had intimations of his mortality. Mantel will explore his ultimate fate in the next book, The Mirror and the Light.

Earlier in Bring Up the Bodies, Henry suffers an accident at jousting and is briefly thought dead. Reflecting on this, Cromwell speaks to his nephew:

That night he says to Richard Cromwell, “It was a bad moment for me. How many men can say, as I must, ‘I am a man whose only friend is the King of England’? I have everything, you would think. And yet take Henry away and I have nothing.”

Richard sees the helpless truth of it. Says, “Yes.” What else can he say?

Karin Kross lives and writes in Austin, TX. She can be found elsewhere on Tumblr and Twitter.